At the end of the wharf was a rakish-looking vessel.

It was the beginning of the second week of July, 1777, and for over a fortnight the outfitting6, loading, and changing had been going on and the nameless vessel that was going on the nameless mission was almost ready to set sail. To tell the truth, although at first there was some mystery made about her ownership, her destination, and her probable calling, there was very little of the mystery left at the time at which this chapter opens. The English spies and sympathizers in Dunkirk were almost95 at their wits’ end. They had informed their Government of their opinions, and now began to write to the English press in order to stir the Government to action.

A copy of the London Times almost a week old had come to the hands of Conyngham. As he glanced through the pages, all at once his own name attracted his attention. This had happened as he was walking down to the wharf, and he had smiled broadly as he perused7 the remarkable8 effusion. He had slipped the paper into his pocket, where, in the interest of watching the vessel’s loading, although he took no active part in its direction, he had forgotten it.

“Everything seems to be going finely, Captain Gustavus,” said Mr. Hodge. “No one apparently9 suspects the ownership of the vessel, and I do not think the French authorities will interfere10 with her sailing.”

Conyngham smiled. That no one seemed to object struck him as having a humorous meaning. Perhaps he had not observed the twinkle in Mr. Hodge’s eye, as he advanced this statement. He was about to refer to the article in the Times when something attracted his attention.

Two men, one dressed as a sailor and the other as something of a court dandy, came walking together down the wharf. The sailorman to all appearances had been drinking and was asking the gentleman with the long satin waistcoat for something more with which to quench11 his thirst. At last the latter, as if he could no longer resist the man’s importuning12, reached into his pocket and, producing a purse, took out a small silver piece. At the same time he addressed some words to the sailor, as if bidding him begone.

96 “I know this fop in satin and lace,” said Hodge. “I have seen him in Paris, but I can not recollect13 where. He’s not a Frenchman, but a German or a Pole.”

“Methinks I know him too,” returned Conyngham. “He’s talking English to that beggar. Well, well—by the great gun!—it comes to me.”

Conyngham lowered his voice almost to a whisper and spoke14 without turning his head or scarcely moving his lips.

“I know both of them now,” he said. “The fop is our friend the English spy, and the other is one of the stool-pigeons. What do you suppose he said just then? Hush15! here he comes in our direction. It is his intention to get near to us and listen to our conversation.”

“Let us move then,” suggested Mr. Hodge, “for there is a good deal about me that I would not wish to have known; besides,” he added, “I think you are mistaken, for I now remember where I have seen this coxcomb16, and at the house of no one less than good Dr. Bancroft, the geographer17 and scientist, the friend of Franklin, and one who had kept us well informed of the British plans.”

“Then keep an eye on Dr. Bancroft, is my advice,” rejoined Conyngham. “Hush! let me speak to this fellow.”

The drunken sailor lurched up and leant with both elbows against a big pine-wood box, but apparently he paid no attention to the proximity18 of the others, for he began emptying his pockets of their contents, which included the silver piece which had just been given him, and searching for some bits of tobacco he jammed them into the bowl of his black heavy pipe.

97 “What you say about the moon may be true,” observed the captain as if carrying on some deep subject, “but still the influence of the orb19 upon the tides has been acknowledged for centuries.”

The sailor by this time had found a bit of flint and steel and was trying to ignite a bit of pocket tinder.

All at once Conyngham turned toward him, and at the same time taking the copy of the Times out of his pocket, he spread it out on the top of the box and began to read aloud.

“Listen to this nonsense,” he said in beginning. “The English must be in a ferment20 of terror to believe such stuff as this,” and forthwith he read:

“I saw Conyngham yesterday. He had engaged a crew of desperate characters to man a vessel of one hundred and thirty tons. She has now Frenchmen on board to deceive our minister here. A fine fast-sailing vessel, handsomely painted blue and yellow, is now at Dunkirk, having powder, small arms, and ammunition21 for her. Conyngham proved the cannon22 himself, and told the bystanders he would play the d——l with the British trade at Havre. It is supposed when the vessel is ready the Frenchmen will yield command to Conyngham and his crew. The vessel is to mount twenty carriage-guns and to have a complement23 of sixty men. She is the fastest sailer now known—no vessel can catch her once out on the ocean.

“I send you timely notice that you may be enabled to take active measures to stay this daring character, who fears not man or government, but sets all at defiance24.

“He had the impudence25 to say if he wanted provisions98 or repairs, he would put into an Irish harbor and obtain them.

“It is vain here to say Conyngham is a pirate. They will tell you he is one brave American; he is ‘a bold Boston.’

“You can not be too soon on the alert to stop the cruise of this daring pirate.

“James Clements.”

There was also a letter that Conyngham read in even a louder tone:

“Paris, July 28, 1777.

“Sir: You have no doubt been informed by your ministry26 that Lord Stormont had been successful, and that the Court of Versailles had declared their ports shut against American privateers. Let your blind politicians sleep, the guns of the American privateers will waken them to their sorrows. The General Mifflin privateer arrived, and Monsieur de Chauffault, the admiral, returned the salute27 in form, as to a vessel from a sovereign and independent state.

“Your papers tell us that Conyngham is in chains in Dunkirk, and is expected shortly in London, to be tried and hung. I tell you that Conyngham is on the ocean, like a lion searching for prey28. Woe29 be to those vessels who come within his grasp. No force intimidates30 him. God and America is his motto. Our country is duped by French artifice31.”

As he finished it was noticeable to both men that the drunken sailor was paying strict attention.

“What’s your opinion of that?” asked Conyngham.

The man looked up slowly and found the captain’s99 eyes fastened upon his own. “I say, what is your opinion of that?” he reiterated32, this time leaning forward and grasping the man by the collar of his open jacket.

So surprised was the latter that the pipe fell from his lips, and before he could control himself an oath followed the pipe—an oath in good round English.

Conyngham affected33 to laugh.

“Why, he has understood everything we’ve been saying,” he said, turning to Mr. Hodge again.

The sailor, who had wrenched34 himself free, started to walk away. His efforts in that direction were accelerated by a well-placed kick, administered by the toe of Conyngham’s boot. But he apparently did not resent it, and still affecting to be under the influence of liquor stumbled up the wharf.

“That will puzzle our friend with the high-heeled boots,” said the captain, “but to tell the truth I think there is very little use in any more secrecy35. They seem to know as much of the situation as we do.”

This was nothing more than the truth, and before two days had passed Conyngham had openly acknowledged it by superintending the placing of the cannon on board of the Revenge, and the French Government had agreed to allow her to depart from the port of Dunkirk, upon Mr. Hodge, who had all through the transaction appeared as her owner, signing a bond that she would do no cruising off the coast of France.

The time of sailing drew on quickly. The vessel was laden36, the ammunition was all on board—there was no secrecy about that now—the crew had been picked and divided into watches; some attempt had even been made to drill them at the guns. The citizens of Dunkirk knew100 almost to a man that the tidy little cruiser would soon be on the sea.

Once more the four “conspirators” were grouped about the table at the tavern37.

“Three days from now, captain, and you will be off the headlands,” observed Mr. Hodge, “and we shall be here waiting to see which way the cat will jump.”

“If you mean Lord Stormont by ‘the cat,’” answered Conyngham, “I think he is all ready for jumping now.”

“I wish,” rejoined the elder Ross, “that we were certain of the French minister’s temper. Dr. Franklin must have had a strong cudgel in his hands to bring him to terms at all. I wonder what it was? You could tell us, Captain Conyngham, if you wished, of that I’m sure.”

Conyngham looked at the others intently. He waited for Hodge to speak, thinking that of course the good doctor had told him of the commission that undoubtedly38 had been the cudgel that had brought the Count de Vergennes to terms. But seeing that Hodge apparently did not wish to refer to it, he also held his peace and changed the subject.

“You say that Dr. Franklin’s secretary will be down from Paris to-morrow?” he asked Mr. Hodge. “I suppose with final instructions.”

The younger Ross laughed. “I don’t think there will be many instructions that we could not guess,” he said. “It seems to me that the case is clear enough—to capture as many of the enemy’s vessels as possible and not to get caught at it, is an easy thing to remember.”

“There will be more than that, my son,” returned Hodge, “much more than that, I hope, for you must remember that I am responsible to the French Government101 for the proper behavior of the gallant39 captain so long as he remains40 on the coast of France.”

“And you have no longing41 for the Bastile, eh?”

“Not much, my son. But Mr. Carmichael will tell us to what length we can go in interpreting the cautions of the ministry.”

After some more desultory42 talk the meeting broke up, another parting toast being drunk to the success of the Revenge.

Mr. Hodge and Conyngham walked down the street toward the pier43 where the captain’s gig was waiting, for he was now living openly on board the Revenge and making no secret of his connection with her.

“Tell me, my good friend,” asked the captain, “did Dr. Franklin say nothing to you about the contents of that packet that you brought to Paris with you? It would seem rather unusual if he did not.”

“Nothing beyond the fact that he was glad to receive it,” was the reply. “What did it contain? You were asked that question before. If you do not care to tell—why, consider it unasked.”

“It contained enough to save my life,” was the reply: “my commission—that was all.”

“You have not received it back?”

“I have not seen or heard of it from that day to this.”

Hodge gave vent44 to a prolonged whistle.

“This is a serious matter,” he said. “But perhaps Carmichael will fetch it down with him.”

“I hope and trust so,” was the reply. “Sure, I don’t care any more for the yard-arm than you do for the Bastile.”

Conyngham was worried and slept little that night,102 still he reasoned that it was more than probable that the commission would be forthcoming in the morning, and also that he would be relieved, from all secrecy as to its possession. He saw that it had worked wonders, and that slowly but surely France and England were verging45 toward war; that before many months should pass America would have a powerful ally. Of course, in view of these circumstances, France could not have given the mortal offense46 of surrendering a regularly commissioned officer into the hands of what soon was to be a common enemy.

The next day Carmichael arrived. He was a tall, spare man, with a hawked47 nose; a broad, good-natured grin was usually on his lips, but he was keen as a whip-lash.

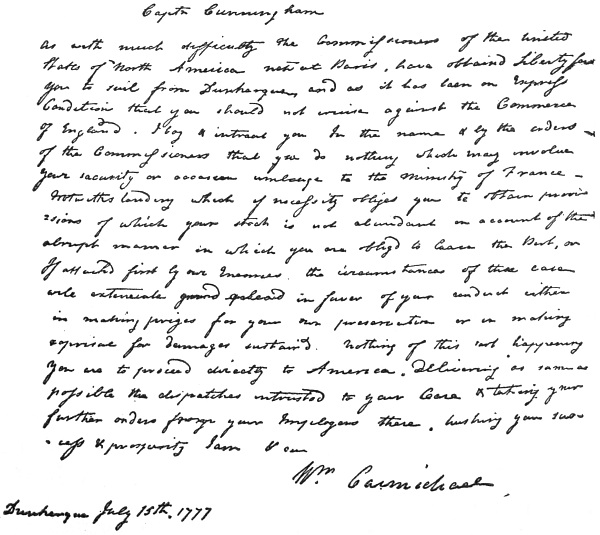

It was the morning of the 15th of July, and in the cabin of the Revenge Mr. Carmichael sat opposite Captain Conyngham, who watched him with a smile of dry amusement as he wrote. Carmichael was smiling also. He had a trick of apparently spelling the letters he was writing with his tongue wriggling48 at the corner of his mouth. As soon as he had finished he turned, and waving the paper in the air to dry it, chuckled49.

“There, Captain Conyngham, are your sailing orders. Of course, to a man of your intelligence, there is no use of being more than explicit50. Somehow I am reminded of a story of one of your fellow countrymen who was accused of killing51 a sheep, and in explanation made the plea that he would kill any sheep that attacked and bit him on the open highway. So all you’ve got to do is to be sure that the sheep bites first.”

“There is another little adage52 about a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” replied Conyngham laughing, “and sure, there are plenty of them in both channels, and in that case——”

103 “Be sure to kill the wolf before he bites you at all. But seriously—once away from the French coast, you ought to have a free foot. Do not send any prizes into French ports. Here is a list of the agents of Lazzonere and Company, Spanish merchants, and here is a draft of a thousand livre upon them at Corunna. Should you desire more, accounting53 will be kept with Hortalez and Company that will be audited54 by the commissioners55 and by Grand, the banker, of Paris. You will receive the usual percentage accruing56 to the captain of a vessel making such captures, and will keep a separate account of your expenditures57 and moneys received and the value of prizes.”

He handed Captain Conyngham the remarkable instructions, which now for the first time are shown to the public in their original form.

Conyngham read the paper through. “But there is something else,” he said. “Did not Dr. Franklin send some other paper to me?”

“Yes, there is a packet here which I received from the secretary of the Cabinet Minister, M. Maurepas, who told me that he had been instructed to give them to me by the Count de Vergennes. They contain some matter in relation to our project.”

He opened his portfolio58, and breaking the seal displayed some pages of closely written matter that was undated and unsigned. It merely stated that Mr. Hodge, merchant, had given his guarantee and bond, together with Messrs. Ross and Allan, that the American vessel about to depart from Dunkirk should respect all English commerce and should make the best of her way to the United States. Conyngham’s name was not even mentioned. As soon as he had read it, the captain exclaimed aloud:

“We are trapped again! By the Powers, there’s a large rat somewhere. Where is my commission? I can not sail without one, and I refuse to put myself and my crew in such jeopardy59.”

“Dr. Franklin spoke to me of the paper that he had given you, and that he had sent to the Count de Vergennes. He understood from the latter that it had been returned to either Mr. Arthur Lee or Mr. Silas Deane, who had sent it to you at this place.”

“I have never received it.”

“Well,” said Mr. Carmichael, “this must be attended to before sailing. We will meet ashore60 this afternoon with Hodge, Allan, and the rest, and hold a council of war. Perhaps I had better see them first, and I will105 ask you to send me off in one of your boats immediately.”

The secretary and the captain repaired on deck. Conyngham felt no little pride in his vessel, and indeed she was one to make the heart of any captain glad. Everything about her was as neat as a pin. Her crew of nearly one hundred men, forty-four of whom were Americans, had picked up wonderfully in their work. On her decks were fourteen six-pounders and twenty small two-pounder swivels capable of making great havoc62 at short range when loaded with grape or ball. He pointed63 out the good points of his vessel to Mr. Carmichael, who appeared in a great hurry to get away, and was soon sent off in the captain’s gig, intending to look up Mr. Hodge as soon as possible.

After drilling the crew all one afternoon, Conyngham early in the evening went ashore, and repaired at once to the usual rendezvous64. There he found the others awaiting him. All seemed to be in good humor.

“Ho, Captain Glumface,” cried Hodge, “sit down with us. I have some news that will give thee comfort.”

“Has it arrived?” asked Conyngham eagerly.

“Hear the man!” replied Hodge. “Look!”

He handed Conyngham a paper.

“It is one that just by luck I found in my possession. A blank commission, and I have dated it to cover your last cruise.”

“But this is a privateersman’s commission,” Conyngham said, looking up from his perusal65 of the paper. “I do not consider myself in that light.”

“I went on your bond,” replied Hodge.

“Yes, but it was not your money that paid for the106 outfitting; it was money belonging to the United Colonies of America, or borrowed on their account, and I am an officer in the regular navy, and that vessel sails under the flag.”

It looked dangerously like a quarrel. Hodge relapsed into silence and the elder Ross looked furtively66 from Mr. Carmichael to the captain, as if expecting the former to come to the rescue.

“What you have there,” said the secretary at last, “is authority enough, and is the same under which many of our cruisers are now sailing. It is a letter of marque respected by the British Admiralty.”

“Mayhap so,” replied Conyngham, “but the date is made out wrong. I sailed in the Surprise on the 1st of May, and this is made out on the 2d.”

“Tut, tut! that is too bad,” muttered Mr. Hodge, “and the last one I’ve got, and in fact the only one I had. What now are we to do?”

“My brother comes down from Paris to-morrow,” put in Ross, “and he may bring news proving that we have time to wait, or perhaps he may have seen Dr. Franklin and have the very paper the captain desires.”

Hardly had he spoken than a sound of hurrying feet came down the hallway outside. The door burst open, and in rushed the younger Ross. Evidently the position of the candles on the table prevented him from seeing that Conyngham was present, for in his first words he asked for him, and upon the latter rising, he came quickly to his side.

“We must think and act quickly,” he cried. “But two hours behind me in the road is a messenger from de Vergennes instructing the authorities to seize the vessel107 and not to allow her to depart. I have this on the very best authority. I saw Dr. Franklin but an hour or so before I received the news. He expected me to wait until to-morrow, when he should have been granted an audience with the Foreign Minister, but upon ascertaining67 the importance of immediate61 action (I was told by the very messenger to whom I had once been presented by Dr. Bancroft) I sought out the doctor. Search high or low, I could not find him, but by good fortune I met Silas Deane in company with our misanthropic68 friend, Mr. Lee. They ordered me to post it here at once and tell you to get under way at the earliest possible moment.”

“Where was Dr. Franklin, do you suppose?” asked Allan.

“Dining with some fair countess or duchess at Versailles,” replied Hodge, who leaned perhaps a little toward the Lee faction69.

The secretary shrugged70 his shoulders and said nothing, but Conyngham spoke quickly.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “there is but one thing to do. Commission or no commission, I sail from Dunkirk on the early morning tide. We have but a few hours before us. May the Powers grant the messenger does not arrive before then. Stormont must have played his trump71 card and won.”

Quickly the party broke up and accompanied Conyngham to the water’s edge. Early in the morning, while still the mist hung over the harbor and shrouded72 the houses and shipping73, a ghostlike vessel appeared in mid-channel, fanned by the damp shore breeze. It was the Revenge. On the fast ebb74 tide she slid swiftly out to sea.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

wharf

|

|

| n.码头,停泊处 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

vessel

|

|

| n.船舶;容器,器皿;管,导管,血管 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

slings

|

|

| 抛( sling的第三人称单数 ); 吊挂; 遣送; 押往 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

bulwarks

|

|

| n.堡垒( bulwark的名词复数 );保障;支柱;舷墙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

vessels

|

|

| n.血管( vessel的名词复数 );船;容器;(具有特殊品质或接受特殊品质的)人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

outfitting

|

|

| v.装备,配置设备,供给服装( outfit的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

perused

|

|

| v.读(某篇文字)( peruse的过去式和过去分词 );(尤指)细阅;审阅;匆匆读或心不在焉地浏览(某篇文字) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

apparently

|

|

| adv.显然地;表面上,似乎 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

interfere

|

|

| v.(in)干涉,干预;(with)妨碍,打扰 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

quench

|

|

| vt.熄灭,扑灭;压制 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

importuning

|

|

| v.纠缠,向(某人)不断要求( importune的现在分词 );(妓女)拉(客) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

recollect

|

|

| v.回忆,想起,记起,忆起,记得 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

spoke

|

|

| n.(车轮的)辐条;轮辐;破坏某人的计划;阻挠某人的行动 v.讲,谈(speak的过去式);说;演说;从某种观点来说 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

hush

|

|

| int.嘘,别出声;n.沉默,静寂;v.使安静 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

coxcomb

|

|

| n.花花公子 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

geographer

|

|

| n.地理学者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

proximity

|

|

| n.接近,邻近 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

orb

|

|

| n.太阳;星球;v.弄圆;成球形 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

ferment

|

|

| vt.使发酵;n./vt.(使)激动,(使)动乱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

ammunition

|

|

| n.军火,弹药 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

cannon

|

|

| n.大炮,火炮;飞机上的机关炮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

complement

|

|

| n.补足物,船上的定员;补语;vt.补充,补足 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

defiance

|

|

| n.挑战,挑衅,蔑视,违抗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

impudence

|

|

| n.厚颜无耻;冒失;无礼 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

ministry

|

|

| n.(政府的)部;牧师 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

salute

|

|

| vi.行礼,致意,问候,放礼炮;vt.向…致意,迎接,赞扬;n.招呼,敬礼,礼炮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

prey

|

|

| n.被掠食者,牺牲者,掠食;v.捕食,掠夺,折磨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

woe

|

|

| n.悲哀,苦痛,不幸,困难;int.用来表达悲伤或惊慌 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

intimidates

|

|

| n.恐吓,威胁( intimidate的名词复数 )v.恐吓,威胁( intimidate的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

artifice

|

|

| n.妙计,高明的手段;狡诈,诡计 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

reiterated

|

|

| 反复地说,重申( reiterate的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

affected

|

|

| adj.不自然的,假装的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

wrenched

|

|

| v.(猛力地)扭( wrench的过去式和过去分词 );扭伤;使感到痛苦;使悲痛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

secrecy

|

|

| n.秘密,保密,隐蔽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

laden

|

|

| adj.装满了的;充满了的;负了重担的;苦恼的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

tavern

|

|

| n.小旅馆,客栈;小酒店 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

gallant

|

|

| adj.英勇的,豪侠的;(向女人)献殷勤的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

longing

|

|

| n.(for)渴望 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

desultory

|

|

| adj.散漫的,无方法的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

pier

|

|

| n.码头;桥墩,桥柱;[建]窗间壁,支柱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

vent

|

|

| n.通风口,排放口;开衩;vt.表达,发泄 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

verging

|

|

| 接近,逼近(verge的现在分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

offense

|

|

| n.犯规,违法行为;冒犯,得罪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

hawked

|

|

| 通过叫卖主动兜售(hawk的过去式与过去分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

wriggling

|

|

| v.扭动,蠕动,蜿蜒行进( wriggle的现在分词 );(使身体某一部位)扭动;耍滑不做,逃避(应做的事等);蠕蠕 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

chuckled

|

|

| 轻声地笑( chuckle的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

explicit

|

|

| adj.详述的,明确的;坦率的;显然的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

killing

|

|

| n.巨额利润;突然赚大钱,发大财 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

adage

|

|

| n.格言,古训 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

accounting

|

|

| n.会计,会计学,借贷对照表 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

audited

|

|

| v.审计,查账( audit的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

commissioners

|

|

| n.专员( commissioner的名词复数 );长官;委员;政府部门的长官 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

accruing

|

|

| v.增加( accrue的现在分词 );(通过自然增长)产生;获得;(使钱款、债务)积累 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

expenditures

|

|

| n.花费( expenditure的名词复数 );使用;(尤指金钱的)支出额;(精力、时间、材料等的)耗费 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

portfolio

|

|

| n.公事包;文件夹;大臣及部长职位 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

jeopardy

|

|

| n.危险;危难 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

ashore

|

|

| adv.在(向)岸上,上岸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

immediate

|

|

| adj.立即的;直接的,最接近的;紧靠的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

havoc

|

|

| n.大破坏,浩劫,大混乱,大杂乱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

pointed

|

|

| adj.尖的,直截了当的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

rendezvous

|

|

| n.约会,约会地点,汇合点;vi.汇合,集合;vt.使汇合,使在汇合地点相遇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

perusal

|

|

| n.细读,熟读;目测 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

furtively

|

|

| adv. 偷偷地, 暗中地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

ascertaining

|

|

| v.弄清,确定,查明( ascertain的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

misanthropic

|

|

| adj.厌恶人类的,憎恶(或蔑视)世人的;愤世嫉俗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

faction

|

|

| n.宗派,小集团;派别;派系斗争 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

shrugged

|

|

| vt.耸肩(shrug的过去式与过去分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

trump

|

|

| n.王牌,法宝;v.打出王牌,吹喇叭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

shrouded

|

|

| v.隐瞒( shroud的过去式和过去分词 );保密 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

shipping

|

|

| n.船运(发货,运输,乘船) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

ebb

|

|

| vi.衰退,减退;n.处于低潮,处于衰退状态 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |