XIV MISS SALISBURY'S STORY

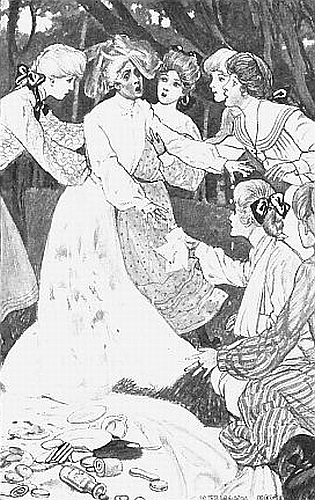

“Oh Miss Anstice!” cried the “Salisbury girls,” jumping to their feet.

“Sister!” exclaimed Miss Salisbury, dropping her plate, and letting all her sweet, peaceful reflections fly to the four winds.

“I never did regard picnics as pleasant affairs,” gasped1 Miss Anstice, as the young hands raised her, “and now they are—quite—quite detestable.” She looked at her gown, alas2! no longer immaculate.

“If you could wipe my hands first, young ladies,” sticking out those members, on which were plentiful3 supplies of marmalade and jelly cake, “I should be much obliged. Never mind the gown yet,” she added with asperity4.

“I'll do that,” cried Alexia, flying at her with two or three napkins.

“Alexia, keep your seat.” Miss Anstice turned on her. “It is quite bad enough, without your heedless fingers at work on it.207”

“I won't touch the old thing,” declared Alexia, in a towering passion, and forgetting it was not one of the girls. “And I may be heedless, but I can be polite,” and she threw down the napkins, and turned her back on the whole thing.

“Alexia!” cried Polly, turning very pale; and, rushing up to her, she bore her away under the trees. “Why, Alexia Rhys, you've talked awfully5 to Miss Anstice—just think, the sister of our Miss Salisbury!”

“Was that old thing a Salisbury?” asked Alexia, quite unmoved. “I thought it was a rude creature that didn't know what it was to have good manners.”

“Alexia, Alexia!” mourned Polly, and for the first time in Alexia's remembrance wringing7 her hands, “to think you should do such a thing!”

Alexia, seeing Polly wring6 her hands, felt quite aghast at herself. “Polly, don't do that,” she begged.

“Oh, I can't help it.” And Polly's tears fell fast.

Alexia gave her one look, as she stood there quite still and pale, unable to stop the tears racing8 over her cheeks, turned, and fled with long steps back to the crowd of girls surrounding poor Miss208 Anstice, Miss Salisbury herself wiping the linen9 gown with an old napkin in her deft10 fingers.

“I beg your pardon,” cried Alexia gustily11, and plunging12 up unsteadily. “I was bad to say such things.”

“You were, indeed,” assented13 Miss Anstice tartly14. “Sister, that is quite enough; the gown cannot possibly be made any better with your incessant15 rubbing.”

Miss Salisbury gave a sigh, and got up from her knees, and put down the napkin. Then she looked at Alexia. “She is very sorry, sister,” she said gently. “I am sure Alexia regrets exceedingly her hasty speech.”

“Hasty?” repeated Miss Anstice, with acrimony, “it was quite impertinent; and I cannot remember when one of our young ladies has done such a thing.”

All the blood in Alexia's body seemed to go to her sallow cheeks when she heard that. That she should be the first and only Salisbury girl to be so bad, quite overcame her, and she looked around for Polly Pepper to help her out. And Polly, who had followed her up to the group, begged, “Do, dear Miss Anstice, forgive her.” And so did all the girls, even those who did not209 like Alexia one bit, feeling sorry for her now. Miss Anstice relented enough to say, “Well, we will say no more about it; I dare say you did not intend to be impertinent.” And then they all sat down again, and everybody tried to be as gay as possible while the feast went on.

And by the time they sang the “Salisbury School Songs,”—for they had several very fine ones, that the different classes had composed,—there was such a tone of good humor prevailing16, everybody getting so very jolly, that no one looking on would have supposed for a moment that a single unpleasant note had been struck. And Miss Anstice tried not to look at her gown; and Miss Salisbury had a pretty pink tinge17 in her cheeks, and her eyes were blue and serene18, without the tired look that often came into them.

“Now for the story—oh, that is the best of all!” exclaimed Polly Pepper, when at last, protesting that they couldn't eat another morsel19, they all got up from the feast, leaving it to the maids.

“Isn't it!” echoed the girls. “Oh, dear Miss Salisbury, I am so glad it is time for you to tell it.” All of which pleased Miss Salisbury very much indeed, for it was the custom at this annual210 festival to wind up the afternoon with a story by the principal, when all the girls would gather at her feet to listen to it, as she sat in state in her stone chair.

“Is it?” she cried, the pink tinge on her cheek getting deeper. “Well, do you know, I think I enjoy, as much as my girls, the telling of this annual story.”

“Oh, you can't enjoy it as much,” said one impulsive20 young voice.

Miss Salisbury smiled indulgently at her. “Well, now, if you are ready, girls, I will begin.”

“Oh, yes, we are—we are,” the bright groups, scattered21 on the grass at her feet, declared.

“To-day I thought I would tell you of my school days when I was as young as you,” began Miss Salisbury.

“Oh—oh!”

“Miss Salisbury, I just love you for that!” exclaimed the impulsive girl, and jumping out of her seat, she ran around the groups to the stone chair. “I do, Miss Salisbury, for I did so want to hear all about when you were a schoolgirl.”

“Well, go back to your place, Fanny, and you shall hear a little of my school life,” said Miss Salisbury gently.211

“No—no; the whole of it,” begged Fanny earnestly, going slowly back.

“My dear child, I could not possibly tell you the whole,” said Miss Salisbury, smiling; “it must be one little picture of my school days.”

“Do sit down, Fanny,” cried one of the other girls impatiently; “you are hindering it all.”

So Fanny flew back to her place, and Miss Salisbury without any more interruptions, began:

“You see, girls, you must know to begin with, that our father—sister's and mine—was a clergyman in a small country parish; and as there were a great many mouths to feed, and young, growing minds to feed as well, besides ours, why there was a great deal of considering as to ways and means constantly going on at the parsonage. Well, as I was the eldest22, of course the question came first, what to do with Amelia.”

“Were you Amelia?” asked Fanny.

“Yes. Well, after talking it over a great deal,—and I suspect many sleepless23 nights spent by my good father and mother,—it was at last decided24 that I should be sent to boarding school; for I forgot to tell you, I had finished at the academy.”

“Yes; sister was very smart,” broke in Miss212 Anstice proudly—“she won't tell you that; so I must.”

“Oh sister, sister,” protested Miss Salisbury.

“Yes, she excelled all the boys and girls.”

“Did they have boys at that school?” interrupted Philena, in amazement25. “Oh, how very nice, Miss Salisbury!”

“I should just love to go to school with boys,” declared ever so many of the girls ecstatically.

“Why don't you take boys at our school, Miss Salisbury?” asked Silvia longingly26.

Miss Anstice looked quite horrified27 at the very idea; but Miss Salisbury laughed. “It is not the custom now, my dear, in private schools. In my day—you must remember that was a long time ago—there were academies where girls and boys attended what would be called a high school now.”

“Oh!”

“And I went to one in the next town until it was thought best for me to be sent to boarding school.”

“And she was very smart; she took all the prizes at the academy, and the principal said—” Miss Anstice was herself brought up quickly by her sister.213

“If you interrupt so much, I never shall finish my story, Anstice,” she said.

“I want the girls to understand this,” said Miss Anstice with decision. “The principal said she was the best educated scholar he had ever seen graduated from Hilltop Academy.”

“Well, now if you have finished,” said Miss Salisbury, laughing, “I will proceed. So I was despatched by my father to a town about thirty miles away, to a boarding school kept by the widow of a clergyman who had been a college classmate. Well, I was sorry to leave all my young brothers and sisters, you may be sure, while my mother—girls, I haven't even now forgotten the pang28 it cost me to kiss my mother good-bye.”

Miss Salisbury stopped suddenly, and let her gaze wander off to the waving tree-tops; and Miss Anstice fell into a revery that kept her face turned away.

“But it was the only way I could get an education; and you know I could not be fitted for a teacher, which was to be my life work, unless I went; so I stifled29 all those dreadful feelings which anticipated my homesickness, and pretty soon I found myself in the boarding school.”214

“How many scholars were there, Miss Salisbury?” asked Laura Page, who was very exact.

“Fifteen girls,” said Miss Salisbury.

“Oh dear me, what a little bit of a school!” exclaimed one girl.

“The schools were not as large in those days,” said Miss Salisbury. “You must keep in mind the great difference between that time and this, my dear. Well, and when I was once there, I had quite enough to do to keep me from being homesick, I can assure you, through the day; because, in addition to lessons, there was the sewing hour.”

“Sewing? Oh my goodness me!” exclaimed Alexia. “You didn't have to sew at that school, did you, Miss Salisbury?”

“I surely did,” replied Miss Salisbury, “and very glad I have been, Alexia, that I learned so much in that sewing hour. I have seriously thought, sister and I, of introducing the plan into our school.”

“Oh, don't, Miss Salisbury,” screamed the girls. “Ple—ase don't make us sew.” Some of them jumped to their feet in distress30.

“I shall die,” declared Alexia tragically31, “if we have to sew.”215

There was such a general gloom settled over the entire party that Miss Salisbury hastened to say, “I don't think, girls, we can do it, because something else equally important would have to be given up to make the time.” At which the faces brightened up.

“Well, I was only to stay at this school a year,” went on Miss Salisbury, “because, you see, it was as much as my father could do to pay for that time; so it was necessary to use every moment to advantage. So I studied pretty hard; and I presume this is one reason why the incident I am going to tell you about was of such a nature; for I was over-tired, though that should be no excuse,” she added hastily.

“Oh sister,” said Miss Anstice nervously32, “don't tell them that story. I wouldn't.”

“It may help them, to have a leaf out of another young person's life, Anstice,” said Miss Salisbury, gravely.

“Well, but—”

“And so, every time when I thought I must give up and go home, I was so hungry to see my father and mother, and the little ones—”

“Was Miss Anstice one of the little ones?” asked Fanny, with a curious look at the crow's-feet and faded eyes of the younger Miss Salisbury.216

“Yes, she was: there were two boys came in between; then Anstice, then Jane, Harriett, Lemuel, and the baby.”

“Oh my!” gasped Alexia, tumbling over into Polly Pepper's lap.

“Eight of us; so you see, it would never do for the one who was having so much money spent upon her, to waste a single penny of it. When I once got to teaching, I was to pay it all back.”

“And did you—did you?” demanded curious Fanny.

“Did she?—oh, girls!” It was Miss Anstice who almost gasped this, making every girl turn around.

“Never mind,” Miss Salisbury telegraphed over their heads, to “sister,” which kept her silent. But she meant to tell sometime.

Polly Pepper, all this time, hadn't moved, but sat with hands folded in her lap. What if she had given up and flown home to Mamsie and the little brown house before Mr. King discovered her homesickness and brought Phronsie! Supposing she hadn't gone in the old stagecoach33 that day when she first left Badgertown to visit in Jasper's home! Just supposing it! She turned217 quite pale, and held her breath, while Miss Salisbury proceeded.

“And now comes the incident that occurred during that boarding-school year, that I have intended for some time to tell you girls, because it may perhaps help you in some experience where you will need the very quality that I lacked on that occasion.”

“Oh sister!” expostulated Miss Anstice.

“It was a midwinter day, cold and clear and piercing.” Miss Salisbury shivered a bit, and drew the shawl put across the back of her stone seat, closer around her. “Mrs. Ferguson—that was the name of the principal—had given the girls a holiday to take them to a neighboring town; there was to be a concert, I remember, and some other treats; and the scholars were, as you would say, 'perfectly34 wild to go,'” and she smiled indulgently at her rapt audience. “Well, I was not going.”

“Oh Miss Salisbury!” exclaimed Amy Garrett in sorrow, as if the disappointment were not forty years in the background.

“No. I decided it was not best for me to take the money, although my father had written me that I could, when the holiday had been planned218 some time before. And besides, I thought I could do some extra studying ahead while the girls were away. Understand, I didn't really think of doing wrong then; although afterward35 I did the wrong thing.”

“Sister!” reproved Miss Anstice. She could not sit still now, but got out of her stone chair, and paced up and down.

“No; I did not dream that in a little while after the party had started, I should be so sorely tempted36, and the idea would enter my head to do the wrong thing. But so it was. I was studying, I remember, my philosophy lesson for some days ahead, when suddenly, as plainly as if letters of light were written down the page, it flashed upon my mind, 'Why don't I go home to-day? I can get back to-night, and no one will know it; at least, not until I am back again, and no harm done.' And without waiting to think it out, I clapped to my book, tossed it on the table, and ran to get my poor little purse out of the bureau drawer.”

The girls, in their eagerness not to lose a word, crowded close to Miss Salisbury's knees, forgetting that she wasn't a girl with them.

“I had quite enough money, I could see, to219 take me home and back on the cars, and by the stage.”

“The stage?” repeated Alexia faintly.

“Yes; you must remember that this time of which I am telling you was many, many years back. Besides, in some country places, it is still the only mode of conveyance37 used.”

Polly Pepper drew a long breath. Dear old Badgertown, and Mr. Tisbett's stage. She could see it now, as it looked when the Five Little Peppers would run to the windows of the little brown house to watch it go lumbering38 by, and to hear the old stage-driver crack his whip in greeting!

“The housekeeper39 had a day off, to go to her daughter's, so that helped my plan along,” Miss Salisbury was saying. “Well would it have been for me if the conditions had been less easy. But I must hasten. I have told you that I did not pause to think; that was my trouble in those days: I acted on impulse often, as schoolgirls are apt perhaps to do, and so I was not ready to stand this sudden temptation. I tied on my bonnet40, gathered up my little purse tightly in my hand; and although the day was cold, the sun was shining brightly, and my heart was so full of hope and anticipation41 that I scarcely thought of220 what I was doing, as I took a thin little jacket instead of the warm cloak my mother had made me for winter wear. I hurried out of the house, when there was no one to notice me, for the maids were careless in the housekeeper's absence, and had slipped off for the moment—at any rate, they said afterward they never saw me;—so off I went.

“I caught the eight o'clock train just in time; which I considered most fortunate. How often afterward did I wish I had missed it! And reasoning within myself as the wheels bore me away, that it was perfectly right to spend the money to go home, for my father had been quite willing for me to take the treat with Mrs. Ferguson and the others, I settled back in my seat, and tried not to feel strange at travelling alone.”

“Oh dear me!” exclaimed the girls, huddling42 up closer to Miss Salisbury's knees. Miss Anstice paced back and forth43; it was too late to stop the story now, and her nervousness could only be walked off.

“But I noticed the farther I got from the boarding school, little doubts would come creeping into my mind,—first, was it very wise for me to have set out in this way? then, was it right?221 And suddenly in a flash, it struck me that I was doing a very wrong thing, and that, if my father and my mother knew it, they would be greatly distressed44. And I would have given worlds, if I had possessed45 them, to be back at Mrs. Ferguson's, studying my philosophy lesson. And I laid my head on the back of the seat before me, and cried as hard as I could.”

Amy sniffed46 into her handkerchief, and two or three other girls coughed as if they had taken cold, while no one looked into her neighbor's face.

“And a wild idea crossed my mind once, of rushing up to the conductor and telling him of my trouble, to ask him if I couldn't get off at the next station and go back; but a minute's reflection told me that this was foolish. There was only the late afternoon train to take me to the school. I had started, and must go on.”

A long sigh went through the group. Miss Anstice seemed to have it communicated to her, for she quickened her pace nervously.

“At last, after what seemed an age to me, though it wasn't really but half an hour since we started, I made up my mind to bear it as well as I could; father and mother would forgive me,222 I was sure, and would make Mrs. Ferguson overlook it—when I glanced out of the car window. Little flakes47 of snow were falling fast. It struck dismay to my heart. If it kept on like this,—and after watching it for some moments, I had no reason to expect otherwise, for it was of that fine, dry quality that seems destined48 to last,—I should not be able to get back to school that afternoon. Oh dear me! And now I began to open my heart to all sorts of fears: the train might be delayed, the stagecoach slow in getting through to Cherryfield. By this time I was in a fine state of nerves, and did not dare to think further.”

One of the girls stole her hand softly up to lay it on that of the principal, forgetting that she had never before dared to do such a thing in all her life. Miss Salisbury smiled, and closed it within her own.

There was a smothered49 chorus of “Oh dears!”

“I sat there, my dears, in a misery50 that saw nothing of the beauty of that storm, knew nothing, heard nothing, except the occasional ejaculations and remarks of the passengers, such as, 'It's going to be the worst storm of the year,' and 'It's come to stay.'223

“Suddenly, without a bit of warning, there was a bumping noise, then the train dragged slowly on, then stopped. All the passengers jumped up, except myself. I was too miserable51 to stir, for I knew now that I was to pay finely for my wrong-doing in leaving the school without permission.”

“Oh—oh!” the girls gave a little scream.

“'What is it—what is it?' the passengers one and all cried, and there was great rushing to the doors, and hopping52 outside to ascertain53 the trouble. I never knew, for I didn't care to ask. It was enough for me that something had broken, and the train had stopped; to start again no one could tell when.”

The sympathy and excitement now were intense. One girl sniffed out from behind her handkerchief, “I—I should have—thought you would—have died—Miss Salisbury.”

“Ah!” said Miss Salisbury, with a sigh, “you will find, Helen, as you grow older, that the only thing you can do to repair in any way the mischief54 you have done, is to keep yourself well under control, and endure the penalty without wasting time on your suffering. So I just made up my mind now to this; and I sat up straight, determined55 not to give way, whatever happened.224

“It was very hard when the impatient passengers would come back into the car to ask each other, 'How soon do you suppose we will get to Mayville?' That was where I was to take the stage.

“'Not till night, if we don't start,' one would answer, trying to be facetious56; but I would torture myself into believing it. At last the conductor came through, and he met a storm of inquiries57, all asking the same question, 'How soon will we get to Mayville?'

“It seemed to me that he was perfectly heartless in tone and manner, as he pulled out his watch to consult it. I can never see a big silver watch to this day, girls, without a shiver.”

The “Salisbury girls” shivered in sympathy, and tried to creep up closer to her.

“Well, the conductor went on to say, that there was no telling,—the railroad officials never commit themselves, you know,—they had telegraphed back to town for another engine (he didn't mention that, after that, we should be sidetracked to allow other trains their right of way), and as soon as they could, why, they would move. Then he proceeded to move himself down the aisle58 in great dignity. Well, my225 dears, you must remember that this all happened long years ago, when accidents to the trains were very slowly made good. We didn't get into Mayville until twelve o'clock. If everything had gone as it should, we ought to have reached there three hours before.”

“Oh my goodness me!” exploded Alexia.

“By this time, the snow had piled up fast. What promised to be a heavy storm had become a reality, and it was whirling and drifting dreadfully. You must remember that I had on my little thin jacket, instead—”

“Oh Miss Salisbury!” screamed several girls, “I forgot that.”

“Don't tell any more,” sobbed59 another—“don't, Miss Salisbury.”

“I want you to hear this story,” said Miss Salisbury quietly. “Remember, I did it all myself. And the saddest part of it is what I made others suffer; not my own distress.”

“Sister, if you only won't proceed!” Miss Anstice abruptly60 leaned over the outer fringe of girls.

“I am getting on to the end,” said Miss Salisbury, with a smile. “Well, girls, I won't prolong the misery for you. I climbed into that stage, it seemed to me, more dead than alive.226 The old stage-driver, showing as much of his face as his big fur cap drawn61 well over his ears would allow, looked at me compassionately62.

“'Sakes alive!' I can hear him now. 'Hain't your folks no sense to let a young thing come out in that way?'

“I was so stiff, all I could think of was, that I had turned into an icicle, and that I was liable to break at any minute. But I couldn't let that criticism pass.

“'They—they didn't let me—I've come from school,' I stammered63.

“He looked at me curiously64, got up from his seat, opened a box under it, and twitched65 out a big cape66, moth-eaten, and well-worn otherwise; but oh, girls, I never loved anything so much in all my life as that horrible old article, for it saved my life.”

A long-drawn breath went around the circle.

“'Here, you just get into this as soon as the next one,' said the stage-driver gruffly, handing it over to me where I sat on the middle seat. I needed no command, but fairly huddled67 myself within it, wrapping it around and around me. And then I knew by the time it took to warm me up, how very cold I had been.227

“And every few minutes of the toilsome journey, for we had to proceed very slowly, the stage-driver would look back over his shoulder to say, 'Be you gittin' any warmer now?' And I would say, 'Yes, thank you, a little.'

“And finally he asked suddenly, 'Do your folks know you're comin'?' And I answered, 'No,' and I hoped he hadn't heard, and I pulled the cape up higher around my face, I was so ashamed. But he had heard, for he whistled; and oh, girls, that made my head sink lower yet. Oh my dears, the shame of wrong-doing is so terrible to bear!

“Well, after a while we got into Cherryfield, along about half-past three o'clock.”

“Oh dear!” exclaimed the young voices.

“I could just distinguish our church spire68 amid the whirling snow; and then a panic seized me. I must get down at some spot where I would not be recognized, for oh, I did not want any one to tell that old stage-driver who I was, and thus bring discredit69 upon my father, the clergyman, for having a daughter who had come away from school without permission. So I mumbled70 out that I was to stop at the Four Corners: that was a short distance from the centre of the village, the usual stopping place.228

“One of the passengers—for I didn't think it was necessary to prolong the story to describe the two women who occupied the back seat—leaned forward and said, 'I hope, Mr. Cheesewell, you ain't goin' to let that girl get out, half froze as she's been, in this snowstorm. You'd ought to go out o' your beat, and carry her home.'

“'Oh, no—no,' I cried in terror, unwinding myself from the big cape and preparing to descend71.

“'Stop there!' roared Mr. Cheesewell at me. 'Did ye s'pose I'd desert that child?' he said to the two women. 'I'd take her home, ef I knew where in creation 'twas.'

“'She lives at the parsonage—she's th' minister's daughter,' said one of the women quietly.

“I sank back in my seat—oh, girls, the bitterness of that moment!—and as well as I could for the gathering72 mist in my eyes, and the blinding storm without, realized the approach to my home. But what a home-coming!

“I managed to hand back the big cape, and to thank Mr. Cheesewell, then stumbled up the little pathway to the parsonage door, feeling229 every step a misery, with all those eyes watching me; and lifting the latch73, I was at home!

“Then I fell flat in the entry, and knew nothing more till I found myself in my own bed, with my mother's face above me; and beyond her, there was father.”

Every girl was sobbing74 now. No one saw Miss Anstice, with the tears raining down her cheeks at the memory that the beautiful prosperity of all these later years could not blot75 out.

“Girls, if my life was saved in the first place by that old cape, it was saved again by one person.”

“Your mother,” gasped Polly Pepper, with wet, shining eyes.

“No; my mother had gone to a sick parishioner's, and father was with her. There was no one but the children at home; the bigger boys were away. I owe my life really to my sister Anstice.”

“Don't!” begged Miss Anstice hoarsely76, and trying to shrink away. The circle of girls whirled around to see her clasping her slender hands tightly together, while she kept her face turned aside.

“Oh girls,” cried Miss Salisbury, with sudden230 energy, “if you could only understand what that sister of mine did for me! I never can tell you. She kept back her own fright, as the small children were so scared when they found me lying there in the entry, for they had all been in the woodshed picking up some kindlings, and didn't hear me come in. And she thought at first I was dead, but she worked over me just as she thought mother would. You see we hadn't any near neighbors, so she couldn't call any one. And at last she piled me all over with blankets just where I lay, for she couldn't lift me, of course, and tucked me in tightly; and telling the children not to cry, but to watch me, she ran a mile, or floundered rather—for the snow was now so deep—to the doctor's house.”

“Oh, that was fine!” cried Polly Pepper, with kindling77 eyes, and turning her flushed face with pride on Miss Anstice. When Miss Salisbury saw that, a happy smile spread over her face, and she beamed on Polly.

“And then, you know the rest; for of course, when I came to myself, the doctor had patched me up. And once within my father's arms, with mother holding my hand—why, I was forgiven.”231

Miss Salisbury paused, and glanced off over the young heads, not trusting herself to speak.

“And how did they know at the school where you were?” Fanny broke in impulsively78.

“Father telegraphed Mrs. Ferguson; and luckily for me, she and her party were delayed by the storm in returning to the school, so the message was handed to her as she left the railroad station. Otherwise, my absence would have plunged79 her in terrible distress.”

“Oh, well, it all came out rightly after all.” Louisa Frink dropped her handkerchief in her lap, and gave a little laugh.

“Came out rightly!” repeated Miss Salisbury sternly, and turning such a glance on Louisa that she wilted80 at once. “Yes, if you can forget that for days the doctor was working to keep me from brain fever; that it took much of my father's hard-earned savings81 to pay him; that it kept me from school, and lost me the marks I had almost gained; that, worst of all, it added lines of care and distress to the faces of my parents; and that my sister who saved me, barely escaped a long fit of sickness from her exposure.”

“Don't, sister, don't,” begged Miss Anstice.

“Came out rightly? Girls, nothing can ever232 come out rightly, unless the steps leading up to the end are right.”

“Ma'am,”—Mr. Kimball suddenly appeared above the fringe of girls surrounding Miss Salisbury,—“there's a storm brewin'; it looks as if 'twas comin' to stay. I'm all hitched82 up, 'n' I give ye my 'pinion83 that we'd better be movin'.”

With that, everybody hopped84 up, for Mr. Kimball's “'pinion” was law in such a case. The picnic party was hastily packed into the barges,—Polly carrying the little green botany case with the ferns for Phronsie's garden carefully on her lap,—and with many backward glances for the dear Glen, off they went, as fast as the horses could swing along.

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

gasped

|

|

| v.喘气( gasp的过去式和过去分词 );喘息;倒抽气;很想要 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

alas

|

|

| int.唉(表示悲伤、忧愁、恐惧等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

plentiful

|

|

| adj.富裕的,丰富的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

asperity

|

|

| n.粗鲁,艰苦 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

awfully

|

|

| adv.可怕地,非常地,极端地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

wring

|

|

| n.扭绞;v.拧,绞出,扭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

wringing

|

|

| 淋湿的,湿透的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

racing

|

|

| n.竞赛,赛马;adj.竞赛用的,赛马用的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

linen

|

|

| n.亚麻布,亚麻线,亚麻制品;adj.亚麻布制的,亚麻的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

deft

|

|

| adj.灵巧的,熟练的(a deft hand 能手) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

gustily

|

|

| adv.暴风地,狂风地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

12

plunging

|

|

| adj.跳进的,突进的v.颠簸( plunge的现在分词 );暴跌;骤降;突降 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

assented

|

|

| 同意,赞成( assent的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

tartly

|

|

| adv.辛辣地,刻薄地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

incessant

|

|

| adj.不停的,连续的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

prevailing

|

|

| adj.盛行的;占优势的;主要的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

tinge

|

|

| vt.(较淡)着色于,染色;使带有…气息;n.淡淡色彩,些微的气息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

serene

|

|

| adj. 安详的,宁静的,平静的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

morsel

|

|

| n.一口,一点点 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

impulsive

|

|

| adj.冲动的,刺激的;有推动力的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

scattered

|

|

| adj.分散的,稀疏的;散步的;疏疏落落的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

eldest

|

|

| adj.最年长的,最年老的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

sleepless

|

|

| adj.不睡眠的,睡不著的,不休息的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

decided

|

|

| adj.决定了的,坚决的;明显的,明确的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

amazement

|

|

| n.惊奇,惊讶 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

longingly

|

|

| adv. 渴望地 热望地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

horrified

|

|

| a.(表现出)恐惧的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

pang

|

|

| n.剧痛,悲痛,苦闷 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

stifled

|

|

| (使)窒息, (使)窒闷( stifle的过去式和过去分词 ); 镇压,遏制; 堵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

distress

|

|

| n.苦恼,痛苦,不舒适;不幸;vt.使悲痛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

tragically

|

|

| adv. 悲剧地,悲惨地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

nervously

|

|

| adv.神情激动地,不安地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

stagecoach

|

|

| n.公共马车 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

afterward

|

|

| adv.后来;以后 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

tempted

|

|

| v.怂恿(某人)干不正当的事;冒…的险(tempt的过去分词) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

conveyance

|

|

| n.(不动产等的)转让,让与;转让证书;传送;运送;表达;(正)运输工具 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

lumbering

|

|

| n.采伐林木 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

housekeeper

|

|

| n.管理家务的主妇,女管家 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

bonnet

|

|

| n.无边女帽;童帽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

anticipation

|

|

| n.预期,预料,期望 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

huddling

|

|

| n. 杂乱一团, 混乱, 拥挤 v. 推挤, 乱堆, 草率了事 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

forth

|

|

| adv.向前;向外,往外 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

distressed

|

|

| 痛苦的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

possessed

|

|

| adj.疯狂的;拥有的,占有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

sniffed

|

|

| v.以鼻吸气,嗅,闻( sniff的过去式和过去分词 );抽鼻子(尤指哭泣、患感冒等时出声地用鼻子吸气);抱怨,不以为然地说 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

flakes

|

|

| 小薄片( flake的名词复数 ); (尤指)碎片; 雪花; 古怪的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

destined

|

|

| adj.命中注定的;(for)以…为目的地的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

smothered

|

|

| (使)窒息, (使)透不过气( smother的过去式和过去分词 ); 覆盖; 忍住; 抑制 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

misery

|

|

| n.痛苦,苦恼,苦难;悲惨的境遇,贫苦 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

miserable

|

|

| adj.悲惨的,痛苦的;可怜的,糟糕的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

hopping

|

|

| n. 跳跃 动词hop的现在分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

ascertain

|

|

| vt.发现,确定,查明,弄清 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

mischief

|

|

| n.损害,伤害,危害;恶作剧,捣蛋,胡闹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

determined

|

|

| adj.坚定的;有决心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

facetious

|

|

| adj.轻浮的,好开玩笑的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

inquiries

|

|

| n.调查( inquiry的名词复数 );疑问;探究;打听 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

aisle

|

|

| n.(教堂、教室、戏院等里的)过道,通道 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

sobbed

|

|

| 哭泣,啜泣( sob的过去式和过去分词 ); 哭诉,呜咽地说 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

abruptly

|

|

| adv.突然地,出其不意地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

drawn

|

|

| v.拖,拉,拔出;adj.憔悴的,紧张的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

compassionately

|

|

| adv.表示怜悯地,有同情心地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

stammered

|

|

| v.结巴地说出( stammer的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

curiously

|

|

| adv.有求知欲地;好问地;奇特地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

twitched

|

|

| vt.& vi.(使)抽动,(使)颤动(twitch的过去式与过去分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

cape

|

|

| n.海角,岬;披肩,短披风 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

huddled

|

|

| 挤在一起(huddle的过去式与过去分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

spire

|

|

| n.(教堂)尖顶,尖塔,高点 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

discredit

|

|

| vt.使不可置信;n.丧失信义;不信,怀疑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

mumbled

|

|

| 含糊地说某事,叽咕,咕哝( mumble的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

descend

|

|

| vt./vi.传下来,下来,下降 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

gathering

|

|

| n.集会,聚会,聚集 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

latch

|

|

| n.门闩,窗闩;弹簧锁 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

sobbing

|

|

| <主方>Ⅰ adj.湿透的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

blot

|

|

| vt.弄脏(用吸墨纸)吸干;n.污点,污渍 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

hoarsely

|

|

| adv.嘶哑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

kindling

|

|

| n. 点火, 可燃物 动词kindle的现在分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

impulsively

|

|

| adv.冲动地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

plunged

|

|

| v.颠簸( plunge的过去式和过去分词 );暴跌;骤降;突降 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

wilted

|

|

| (使)凋谢,枯萎( wilt的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

savings

|

|

| n.存款,储蓄 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

hitched

|

|

| (免费)搭乘他人之车( hitch的过去式和过去分词 ); 搭便车; 攀上; 跃上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

pinion

|

|

| v.束缚;n.小齿轮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

hopped

|

|

| 跳上[下]( hop的过去式和过去分词 ); 单足蹦跳; 齐足(或双足)跳行; 摘葎草花 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |