We were fairly accustomed to receive weird1 telegrams at Baker2 Street, but I have a particular recollection of one which reached us on a gloomy February morning, some seven or eight years ago, and gave Mr. Sherlock Holmes a puzzled quarter of an hour. It was addressed to him, and ran thus:

Please await me. Terrible misfortune. Right wing three-quarter missing, indispensable to-morrow. OVERTON.

"Strand3 postmark, and dispatched ten thirty-six," said Holmes, reading it over and over. "Mr. Overton was evidently considerably4 excited when he sent it, and somewhat incoherent in consequence. Well, well, he will be here, I daresay, by the time I have looked through the TIMES, and then we shall know all about it. Even the most insignificant5 problem would be welcome in these stagnant6 days."

Things had indeed been very slow with us, and I had learned to dread7 such periods of inaction, for I knew by experience that my companion's brain was so abnormally active that it was dangerous to leave it without material upon which to work. For years I had gradually weaned him from that drug mania8 which had threatened once to check his remarkable9 career. Now I knew that under ordinary conditions he no longer craved10 for this artificial stimulus11, but I was well aware that the fiend was not dead but sleeping, and I have known that the sleep was a light one and the waking near when in periods of idleness I have seen the drawn12 look upon Holmes's ascetic13 face, and the brooding of his deep-set and inscrutable eyes. Therefore I blessed this Mr. Overton whoever he might be, since he had come with his enigmatic message to break that dangerous calm which brought more peril14 to my friend than all the storms of his tempestuous15 life.

As we had expected, the telegram was soon followed by its sender, and the card of Mr. Cyril Overton, Trinity College, Cambridge, announced the arrival of an enormous young man, sixteen stone of solid bone and muscle, who spanned the doorway16 with his broad shoulders, and looked from one of us to the other with a comely17 face which was haggard with anxiety.

"Mr. Sherlock Holmes?"

My companion bowed.

"I've been down to Scotland Yard, Mr. Holmes. I saw Inspector18 Stanley Hopkins. He advised me to come to you. He said the case, so far as he could see, was more in your line than in that of the regular police."

"Pray sit down and tell me what is the matter."

"It's awful, Mr. Holmes—simply awful I wonder my hair isn't gray. Godfrey Staunton—you've heard of him, of course? He's simply the hinge that the whole team turns on. I'd rather spare two from the pack, and have Godfrey for my three-quarter line. Whether it's passing, or tackling, or dribbling19, there's no one to touch him, and then, he's got the head, and can hold us all together. What am I to do? That's what I ask you, Mr. Holmes. There's Moorhouse, first reserve, but he is trained as a half, and he always edges right in on to the scrum instead of keeping out on the touchline. He's a fine place-kick, it's true, but then he has no judgment20, and he can't sprint21 for nuts. Why, Morton or Johnson, the Oxford22 fliers, could romp23 round him. Stevenson is fast enough, but he couldn't drop from the twenty-five line, and a three-quarter who can't either punt or drop isn't worth a place for pace alone. No, Mr. Holmes, we are done unless you can help me to find Godfrey Staunton."

My friend had listened with amused surprise to this long speech, which was poured forth24 with extraordinary vigour25 and earnestness, every point being driven home by the slapping of a brawny26 hand upon the speaker's knee. When our visitor was silent Holmes stretched out his hand and took down letter "S" of his commonplace book. For once he dug in vain into that mine of varied27 information.

"There is Arthur H. Staunton, the rising young forger," said he, "and there was Henry Staunton, whom I helped to hang, but Godfrey Staunton is a new name to me."

It was our visitor's turn to look surprised.

"Why, Mr. Holmes, I thought you knew things," said he. "I suppose, then, if you have never heard of Godfrey Staunton, you don't know Cyril Overton either?"

Holmes shook his head good humouredly.

"Great Scott!" cried the athlete. "Why, I was first reserve for England against Wales, and I've skippered the 'Varsity all this year. But that's nothing! I didn't think there was a soul in England who didn't know Godfrey Staunton, the crack three-quarter, Cambridge, Blackheath, and five Internationals. Good Lord! Mr. Holmes, where HAVE you lived?"

Holmes laughed at the young giant's naive28 astonishment29.

"You live in a different world to me, Mr. Overton—a sweeter and healthier one. My ramifications30 stretch out into many sections of society, but never, I am happy to say, into amateur sport, which is the best and soundest thing in England. However, your unexpected visit this morning shows me that even in that world of fresh air and fair play, there may be work for me to do. So now, my good sir, I beg you to sit down and to tell me, slowly and quietly, exactly what it is that has occurred, and how you desire that I should help you."

Young Overton's face assumed the bothered look of the man who is more accustomed to using his muscles than his wits, but by degrees, with many repetitions and obscurities which I may omit from his narrative31, he laid his strange story before us.

"It's this way, Mr. Holmes. As I have said, I am the skipper of the Rugger team of Cambridge 'Varsity, and Godfrey Staunton is my best man. To-morrow we play Oxford. Yesterday we all came up, and we settled at Bentley's private hotel. At ten o'clock I went round and saw that all the fellows had gone to roost, for I believe in strict training and plenty of sleep to keep a team fit. I had a word or two with Godfrey before he turned in. He seemed to me to be pale and bothered. I asked him what was the matter. He said he was all right—just a touch of headache. I bade him good-night and left him. Half an hour later, the porter tells me that a rough-looking man with a beard called with a note for Godfrey. He had not gone to bed, and the note was taken to his room. Godfrey read it, and fell back in a chair as if he had been pole-axed. The porter was so scared that he was going to fetch me, but Godfrey stopped him, had a drink of water, and pulled himself together. Then he went downstairs, said a few words to the man who was waiting in the hall, and the two of them went off together. The last that the porter saw of them, they were almost running down the street in the direction of the Strand. This morning Godfrey's room was empty, his bed had never been slept in, and his things were all just as I had seen them the night before. He had gone off at a moment's notice with this stranger, and no word has come from him since. I don't believe he will ever come back. He was a sportsman, was Godfrey, down to his marrow32, and he wouldn't have stopped his training and let in his skipper if it were not for some cause that was too strong for him. No: I feel as if he were gone for good, and we should never see him again."

Sherlock Holmes listened with the deepest attention to this singular narrative.

"What did you do?" he asked.

"I wired to Cambridge to learn if anything had been heard of him there. I have had an answer. No one has seen him."

"Could he have got back to Cambridge?"

"Yes, there is a late train—quarter-past eleven."

"But, so far as you can ascertain33, he did not take it?"

"No, he has not been seen."

"What did you do next?"

"I wired to Lord Mount-James."

"Why to Lord Mount-James?"

"Godfrey is an orphan34, and Lord Mount-James is his nearest relative—his uncle, I believe."

"Indeed. This throws new light upon the matter. Lord Mount-James is one of the richest men in England."

"So I've heard Godfrey say."

"And your friend was closely related?"

"Yes, he was his heir, and the old boy is nearly eighty—cram full of gout, too. They say he could chalk his billiard-cue with his knuckles35. He never allowed Godfrey a shilling in his life, for he is an absolute miser36, but it will all come to him right enough."

"Have you heard from Lord Mount-James?"

"No."

"What motive37 could your friend have in going to Lord Mount-James?"

"Well, something was worrying him the night before, and if it was to do with money it is possible that he would make for his nearest relative, who had so much of it, though from all I have heard he would not have much chance of getting it. Godfrey was not fond of the old man. He would not go if he could help it."

"Well, we can soon determine that. If your friend was going to his relative, Lord Mount-James, you have then to explain the visit of this rough-looking fellow at so late an hour, and the agitation38 that was caused by his coming."

Cyril Overton pressed his hands to his head. "I can make nothing of it," said he.

"Well, well, I have a clear day, and I shall be happy to look into the matter," said Holmes. "I should strongly recommend you to make your preparations for your match without reference to this young gentleman. It must, as you say, have been an overpowering necessity which tore him away in such a fashion, and the same necessity is likely to hold him away. Let us step round together to the hotel, and see if the porter can throw any fresh light upon the matter."

Sherlock Holmes was a past-master in the art of putting a humble39 witness at his ease, and very soon, in the privacy of Godfrey Staunton's abandoned room, he had extracted all that the porter had to tell. The visitor of the night before was not a gentleman, neither was he a workingman. He was simply what the porter described as a "medium-looking chap," a man of fifty, beard grizzled, pale face, quietly dressed. He seemed himself to be agitated40. The porter had observed his hand trembling when he had held out the note. Godfrey Staunton had crammed41 the note into his pocket. Staunton had not shaken hands with the man in the hall. They had exchanged a few sentences, of which the porter had only distinguished42 the one word "time." Then they had hurried off in the manner described. It was just half-past ten by the hall clock.

"Let me see," said Holmes, seating himself on Staunton's bed. "You are the day porter, are you not?"

"Yes, sir, I go off duty at eleven."

"The night porter saw nothing, I suppose?"

"No, sir, one theatre party came in late. No one else."

"Were you on duty all day yesterday?"

"Yes, sir."

"Did you take any messages to Mr. Staunton?"

"Yes, sir, one telegram."

"Ah! that's interesting. What o'clock was this?"

"About six."

"Where was Mr. Staunton when he received it?"

"Here in his room."

"Were you present when he opened it?"

"Yes, sir, I waited to see if there was an answer."

"Well, was there?"

"Yes, sir, he wrote an answer."

"Did you take it?"

"No, he took it himself."

"But he wrote it in your presence."

"Yes, sir. I was standing43 by the door, and he with his back turned at that table. When he had written it, he said: 'All right, porter, I will take this myself.'"

"What did he write it with?"

"A pen, sir."

"Was the telegraphic form one of these on the table?"

"Yes, sir, it was the top one."

Holmes rose. Taking the forms, he carried them over to the window and carefully examined that which was uppermost.

"It is a pity he did not write in pencil," said he, throwing them down again with a shrug44 of disappointment. "As you have no doubt frequently observed, Watson, the impression usually goes through—a fact which has dissolved many a happy marriage. However, I can find no trace here. I rejoice, however, to perceive that he wrote with a broad-pointed quill45 pen, and I can hardly doubt that we will find some impression upon this blotting-pad. Ah, yes, surely this is the very thing!"

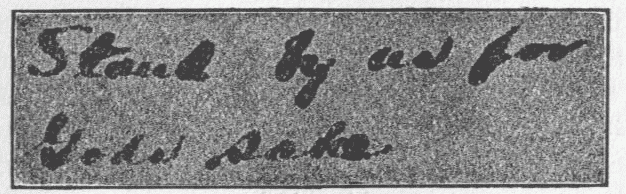

He tore off a strip of the blotting-paper and turned towards us the following hieroglyphic46:

Cyril Overton was much excited. "Hold it to the glass!" he cried.

"That is unnecessary," said Holmes. "The paper is thin, and the reverse will give the message. Here it is." He turned it over, and we read:

"So that is the tail end of the telegram which Godfrey Staunton dispatched within a few hours of his disappearance47. There are at least six words of the message which have escaped us; but what remains48—'Stand by us for God's sake!'—proves that this young man saw a formidable danger which approached him, and from which someone else could protect him. 'US,' mark you! Another person was involved. Who should it be but the pale-faced, bearded man, who seemed himself in so nervous a state? What, then, is the connection between Godfrey Staunton and the bearded man? And what is the third source from which each of them sought for help against pressing danger? Our inquiry49 has already narrowed down to that."

"We have only to find to whom that telegram is addressed," I suggested.

"Exactly, my dear Watson. Your reflection, though profound, had already crossed my mind. But I daresay it may have come to your notice that, counterfoil50 of another man's message, there may be some disinclination on the part of the officials to oblige you. There is so much red tape in these matters. However, I have no doubt that with a little delicacy51 and finesse52 the end may be attained54. Meanwhile, I should like in your presence, Mr. Overton, to go through these papers which have been left upon the table."

There were a number of letters, bills, and notebooks, which Holmes turned over and examined with quick, nervous fingers and darting55, penetrating56 eyes. "Nothing here," he said, at last. "By the way, I suppose your friend was a healthy young fellow—nothing amiss with him?"

"Sound as a bell."

"Have you ever known him ill?"

"Not a day. He has been laid up with a hack57, and once he slipped his knee-cap, but that was nothing."

"Perhaps he was not so strong as you suppose. I should think he may have had some secret trouble. With your assent58, I will put one or two of these papers in my pocket, in case they should bear upon our future inquiry."

"One moment—one moment!" cried a querulous voice, and we looked up to find a queer little old man, jerking and twitching59 in the doorway. He was dressed in rusty60 black, with a very broad-brimmed top-hat and a loose white necktie—the whole effect being that of a very rustic61 parson or of an undertaker's mute. Yet, in spite of his shabby and even absurd appearance, his voice had a sharp crackle, and his manner a quick intensity62 which commanded attention.

"Who are you, sir, and by what right do you touch this gentleman's papers?" he asked.

"I am a private detective, and I am endeavouring to explain his disappearance."

"Oh, you are, are you? And who instructed you, eh?"

"This gentleman, Mr. Staunton's friend, was referred to me by Scotland Yard."

"Who are you, sir?"

"I am Cyril Overton."

"Then it is you who sent me a telegram. My name is Lord Mount-James. I came round as quickly as the Bayswater bus would bring me. So you have instructed a detective?"

"Yes, sir."

"And are you prepared to meet the cost?"

"I have no doubt, sir, that my friend Godfrey, when we find him, will be prepared to do that."

"But if he is never found, eh? Answer me that!"

"In that case, no doubt his family——"

"Nothing of the sort, sir!" screamed the little man. "Don't look to me for a penny—not a penny! You understand that, Mr. Detective! I am all the family that this young man has got, and I tell you that I am not responsible. If he has any expectations it is due to the fact that I have never wasted money, and I do not propose to begin to do so now. As to those papers with which you are making so free, I may tell you that in case there should be anything of any value among them, you will be held strictly63 to account for what you do with them."

"Very good, sir," said Sherlock Holmes. "May I ask, in the meanwhile, whether you have yourself any theory to account for this young man's disappearance?"

"No, sir, I have not. He is big enough and old enough to look after himself, and if he is so foolish as to lose himself, I entirely64 refuse to accept the responsibility of hunting for him."

"I quite understand your position," said Holmes, with a mischievous65 twinkle in his eyes. "Perhaps you don't quite understand mine. Godfrey Staunton appears to have been a poor man. If he has been kidnapped, it could not have been for anything which he himself possesses. The fame of your wealth has gone abroad, Lord Mount-James, and it is entirely possible that a gang of thieves have secured your nephew in order to gain from him some information as to your house, your habits, and your treasure."

The face of our unpleasant little visitor turned as white as his neckcloth.

"Heavens, sir, what an idea! I never thought of such villainy! What inhuman66 rogues67 there are in the world! But Godfrey is a fine lad—a staunch lad. Nothing would induce him to give his old uncle away. I'll have the plate moved over to the bank this evening. In the meantime spare no pains, Mr. Detective! I beg you to leave no stone unturned to bring him safely back. As to money, well, so far as a fiver or even a tenner goes you can always look to me."

Even in his chastened frame of mind, the noble miser could give us no information which could help us, for he knew little of the private life of his nephew. Our only clue lay in the truncated68 telegram, and with a copy of this in his hand Holmes set forth to find a second link for his chain. We had shaken off Lord Mount-James, and Overton had gone to consult with the other members of his team over the misfortune which had befallen them.

There was a telegraph-office at a short distance from the hotel. We halted outside it.

"It's worth trying, Watson," said Holmes. "Of course, with a warrant we could demand to see the counterfoils69, but we have not reached that stage yet. I don't suppose they remember faces in so busy a place. Let us venture it."

"I am sorry to trouble you," said he, in his blandest70 manner, to the young woman behind the grating; "there is some small mistake about a telegram I sent yesterday. I have had no answer, and I very much fear that I must have omitted to put my name at the end. Could you tell me if this was so?"

The young woman turned over a sheaf of counterfoils.

"What o'clock was it?" she asked.

"A little after six."

"Whom was it to?"

Holmes put his finger to his lips and glanced at me. "The last words in it were 'For God's sake,'" he whispered, confidentially72; "I am very anxious at getting no answer."

The young woman separated one of the forms.

"This is it. There is no name," said she, smoothing it out upon the counter.

"Then that, of course, accounts for my getting no answer," said Holmes. "Dear me, how very stupid of me, to be sure! Good-morning, miss, and many thanks for having relieved my mind." He chuckled73 and rubbed his hands when we found ourselves in the street once more.

"Well?" I asked.

"We progress, my dear Watson, we progress. I had seven different schemes for getting a glimpse of that telegram, but I could hardly hope to succeed the very first time."

"And what have you gained?"

"A starting-point for our investigation74." He hailed a cab. "King's Cross Station," said he.

"We have a journey, then?"

"Yes, I think we must run down to Cambridge together. All the indications seem to me to point in that direction."

"Tell me," I asked, as we rattled75 up Gray's Inn Road, "have you any suspicion yet as to the cause of the disappearance? I don't think that among all our cases I have known one where the motives76 are more obscure. Surely you don't really imagine that he may be kidnapped in order to give information against his wealthy uncle?"

"I confess, my dear Watson, that that does not appeal to me as a very probable explanation. It struck me, however, as being the one which was most likely to interest that exceedingly unpleasant old person."

"It certainly did that; but what are your alternatives?"

"I could mention several. You must admit that it is curious and suggestive that this incident should occur on the eve of this important match, and should involve the only man whose presence seems essential to the success of the side. It may, of course, be a coincidence, but it is interesting. Amateur sport is free from betting, but a good deal of outside betting goes on among the public, and it is possible that it might be worth someone's while to get at a player as the ruffians of the turf get at a race-horse. There is one explanation. A second very obvious one is that this young man really is the heir of a great property, however modest his means may at present be, and it is not impossible that a plot to hold him for ransom77 might be concocted78."

"These theories take no account of the telegram."

"Quite true, Watson. The telegram still remains the only solid thing with which we have to deal, and we must not permit our attention to wander away from it. It is to gain light upon the purpose of this telegram that we are now upon our way to Cambridge. The path of our investigation is at present obscure, but I shall be very much surprised if before evening we have not cleared it up, or made a considerable advance along it."

It was already dark when we reached the old university city. Holmes took a cab at the station and ordered the man to drive to the house of Dr. Leslie Armstrong. A few minutes later, we had stopped at a large mansion79 in the busiest thoroughfare. We were shown in, and after a long wait were at last admitted into the consulting-room, where we found the doctor seated behind his table.

It argues the degree in which I had lost touch with my profession that the name of Leslie Armstrong was unknown to me. Now I am aware that he is not only one of the heads of the medical school of the university, but a thinker of European reputation in more than one branch of science. Yet even without knowing his brilliant record one could not fail to be impressed by a mere80 glance at the man, the square, massive face, the brooding eyes under the thatched brows, and the granite81 moulding of the inflexible82 jaw83. A man of deep character, a man with an alert mind, grim, ascetic, self-contained, formidable—so I read Dr. Leslie Armstrong. He held my friend's card in his hand, and he looked up with no very pleased expression upon his dour84 features.

"I have heard your name, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, and I am aware of your profession—one of which I by no means approve."

"In that, Doctor, you will find yourself in agreement with every criminal in the country," said my friend, quietly.

"So far as your efforts are directed towards the suppression of crime, sir, they must have the support of every reasonable member of the community, though I cannot doubt that the official machinery85 is amply sufficient for the purpose. Where your calling is more open to criticism is when you pry86 into the secrets of private individuals, when you rake up family matters which are better hidden, and when you incidentally waste the time of men who are more busy than yourself. At the present moment, for example, I should be writing a treatise87 instead of conversing88 with you."

"No doubt, Doctor; and yet the conversation may prove more important than the treatise. Incidentally, I may tell you that we are doing the reverse of what you very justly blame, and that we are endeavouring to prevent anything like public exposure of private matters which must necessarily follow when once the case is fairly in the hands of the official police. You may look upon me simply as an irregular pioneer, who goes in front of the regular forces of the country. I have come to ask you about Mr. Godfrey Staunton."

"What about him?"

"You know him, do you not?"

"He is an intimate friend of mine."

"You are aware that he has disappeared?"

"Ah, indeed!" There was no change of expression in the rugged89 features of the doctor.

"He left his hotel last night—he has not been heard of."

"No doubt he will return."

"To-morrow is the 'Varsity football match."

"I have no sympathy with these childish games. The young man's fate interests me deeply, since I know him and like him. The football match does not come within my horizon at all."

"I claim your sympathy, then, in my investigation of Mr. Staunton's fate. Do you know where he is?"

"Certainly not."

"You have not seen him since yesterday?"

"No, I have not."

"Was Mr. Staunton a healthy man?"

"Absolutely."

"Did you ever know him ill?"

"Never."

Holmes popped a sheet of paper before the doctor's eyes. "Then perhaps you will explain this receipted bill for thirteen guineas, paid by Mr. Godfrey Staunton last month to Dr. Leslie Armstrong, of Cambridge. I picked it out from among the papers upon his desk."

The doctor flushed with anger.

"I do not feel that there is any reason why I should render an explanation to you, Mr. Holmes."

Holmes replaced the bill in his notebook. "If you prefer a public explanation, it must come sooner or later," said he. "I have already told you that I can hush90 up that which others will be bound to publish, and you would really be wiser to take me into your complete confidence."

"I know nothing about it."

"Did you hear from Mr. Staunton in London?"

"Certainly not."

"Dear me, dear me—the postoffice again!" Holmes sighed, wearily. "A most urgent telegram was dispatched to you from London by Godfrey Staunton at six-fifteen yesterday evening—a telegram which is undoubtedly91 associated with his disappearance—and yet you have not had it. It is most culpable92. I shall certainly go down to the office here and register a complaint."

Dr. Leslie Armstrong sprang up from behind his desk, and his dark face was crimson93 with fury.

"I'll trouble you to walk out of my house, sir," said he. "You can tell your employer, Lord Mount-James, that I do not wish to have anything to do either with him or with his agents. No, sir—not another word!" He rang the bell furiously. "John, show these gentlemen out!" A pompous94 butler ushered95 us severely96 to the door, and we found ourselves in the street. Holmes burst out laughing.

"Dr. Leslie Armstrong is certainly a man of energy and character," said he. "I have not seen a man who, if he turns his talents that way, was more calculated to fill the gap left by the illustrious Moriarty. And now, my poor Watson, here we are, stranded97 and friendless in this inhospitable town, which we cannot leave without abandoning our case. This little inn just opposite Armstrong's house is singularly adapted to our needs. If you would engage a front room and purchase the necessaries for the night, I may have time to make a few inquiries98."

These few inquiries proved, however, to be a more lengthy99 proceeding100 than Holmes had imagined, for he did not return to the inn until nearly nine o'clock. He was pale and dejected, stained with dust, and exhausted101 with hunger and fatigue102. A cold supper was ready upon the table, and when his needs were satisfied and his pipe alight he was ready to take that half comic and wholly philosophic103 view which was natural to him when his affairs were going awry104. The sound of carriage wheels caused him to rise and glance out of the window. A brougham and pair of grays, under the glare of a gas-lamp, stood before the doctor's door.

"It's been out three hours," said Holmes; "started at half-past six, and here it is back again. That gives a radius105 of ten or twelve miles, and he does it once, or sometimes twice, a day."

"No unusual thing for a doctor in practice."

"But Armstrong is not really a doctor in practice. He is a lecturer and a consultant106, but he does not care for general practice, which distracts him from his literary work. Why, then, does he make these long journeys, which must be exceedingly irksome to him, and who is it that he visits?"

"His coachman——"

"My dear Watson, can you doubt that it was to him that I first applied107? I do not know whether it came from his own innate108 depravity or from the promptings of his master, but he was rude enough to set a dog at me. Neither dog nor man liked the look of my stick, however, and the matter fell through. Relations were strained after that, and further inquiries out of the question. All that I have learned I got from a friendly native in the yard of our own inn. It was he who told me of the doctor's habits and of his daily journey. At that instant, to give point to his words, the carriage came round to the door."

"Could you not follow it?"

"Excellent, Watson! You are scintillating109 this evening. The idea did cross my mind. There is, as you may have observed, a bicycle shop next to our inn. Into this I rushed, engaged a bicycle, and was able to get started before the carriage was quite out of sight. I rapidly overtook it, and then, keeping at a discreet110 distance of a hundred yards or so, I followed its lights until we were clear of the town. We had got well out on the country road, when a somewhat mortifying111 incident occurred. The carriage stopped, the doctor alighted, walked swiftly back to where I had also halted, and told me in an excellent sardonic112 fashion that he feared the road was narrow, and that he hoped his carriage did not impede113 the passage of my bicycle. Nothing could have been more admirable than his way of putting it. I at once rode past the carriage, and, keeping to the main road, I went on for a few miles, and then halted in a convenient place to see if the carriage passed. There was no sign of it, however, and so it became evident that it had turned down one of several side roads which I had observed. I rode back, but again saw nothing of the carriage, and now, as you perceive, it has returned after me. Of course, I had at the outset no particular reason to connect these journeys with the disappearance of Godfrey Staunton, and was only inclined to investigate them on the general grounds that everything which concerns Dr. Armstrong is at present of interest to us, but, now that I find he keeps so keen a look-out upon anyone who may follow him on these excursions, the affair appears more important, and I shall not be satisfied until I have made the matter clear."

"We can follow him to-morrow."

"Can we? It is not so easy as you seem to think. You are not familiar with Cambridgeshire scenery, are you? It does not lend itself to concealment114. All this country that I passed over to-night is as flat and clean as the palm of your hand, and the man we are following is no fool, as he very clearly showed to-night. I have wired to Overton to let us know any fresh London developments at this address, and in the meantime we can only concentrate our attention upon Dr. Armstrong, whose name the obliging young lady at the office allowed me to read upon the counterfoil of Staunton's urgent message. He knows where the young man is—to that I'll swear, and if he knows, then it must be our own fault if we cannot manage to know also. At present it must be admitted that the odd trick is in his possession, and, as you are aware, Watson, it is not my habit to leave the game in that condition."

And yet the next day brought us no nearer to the solution of the mystery. A note was handed in after breakfast, which Holmes passed across to me with a smile.

SIR [it ran]:

I can assure you that you are wasting your time in dogging my movements. I have, as you discovered last night, a window at the back of my brougham, and if you desire a twenty-mile ride which will lead you to the spot from which you started, you have only to follow me. Meanwhile, I can inform you that no spying upon me can in any way help Mr. Godfrey Staunton, and I am convinced that the best service you can do to that gentleman is to return at once to London and to report to your employer that you are unable to trace him. Your time in Cambridge will certainly be wasted. Yours faithfully, LESLIE ARMSTRONG.

"An outspoken115, honest antagonist116 is the doctor," said Holmes. "Well, well, he excites my curiosity, and I must really know before I leave him."

"His carriage is at his door now," said I. "There he is stepping into it. I saw him glance up at our window as he did so. Suppose I try my luck upon the bicycle?"

"No, no, my dear Watson! With all respect for your natural acumen117, I do not think that you are quite a match for the worthy118 doctor. I think that possibly I can attain53 our end by some independent explorations of my own. I am afraid that I must leave you to your own devices, as the appearance of TWO inquiring strangers upon a sleepy countryside might excite more gossip than I care for. No doubt you will find some sights to amuse you in this venerable city, and I hope to bring back a more favourable119 report to you before evening."

Once more, however, my friend was destined120 to be disappointed. He came back at night weary and unsuccessful.

"I have had a blank day, Watson. Having got the doctor's general direction, I spent the day in visiting all the villages upon that side of Cambridge, and comparing notes with publicans and other local news agencies. I have covered some ground. Chesterton, Histon, Waterbeach, and Oakington have each been explored, and have each proved disappointing. The daily appearance of a brougham and pair could hardly have been overlooked in such Sleepy Hollows. The doctor has scored once more. Is there a telegram for me?"

"Yes, I opened it. Here it is:

"Ask for Pompey from Jeremy Dixon, Trinity College."

"I don't understand it."

"Oh, it is clear enough. It is from our friend Overton, and is in answer to a question from me. I'll just send round a note to Mr. Jeremy Dixon, and then I have no doubt that our luck will turn. By the way, is there any news of the match?"

"Yes, the local evening paper has an excellent account in its last edition. Oxford won by a goal and two tries. The last sentences of the description say:

"'The defeat of the Light Blues121 may be entirely attributed to the unfortunate absence of the crack International, Godfrey Staunton, whose want was felt at every instant of the game. The lack of combination in the three-quarter line and their weakness both in attack and defence more than neutralized122 the efforts of a heavy and hard-working pack.'"

"Then our friend Overton's forebodings have been justified," said Holmes. "Personally I am in agreement with Dr. Armstrong, and football does not come within my horizon. Early to bed to-night, Watson, for I foresee that to-morrow may be an eventful day."

I was horrified123 by my first glimpse of Holmes next morning, for he sat by the fire holding his tiny hypodermic syringe. I associated that instrument with the single weakness of his nature, and I feared the worst when I saw it glittering in his hand. He laughed at my expression of dismay and laid it upon the table.

"No, no, my dear fellow, there is no cause for alarm. It is not upon this occasion the instrument of evil, but it will rather prove to be the key which will unlock our mystery. On this syringe I base all my hopes. I have just returned from a small scouting124 expedition, and everything is favourable. Eat a good breakfast, Watson, for I propose to get upon Dr. Armstrong's trail to-day, and once on it I will not stop for rest or food until I run him to his burrow125."

"In that case," said I, "we had best carry our breakfast with us, for he is making an early start. His carriage is at the door."

"Never mind. Let him go. He will be clever if he can drive where I cannot follow him. When you have finished, come downstairs with me, and I will introduce you to a detective who is a very eminent126 specialist in the work that lies before us."

When we descended127 I followed Holmes into the stable yard, where he opened the door of a loose-box and led out a squat128, lop-eared, white-and-tan dog, something between a beagle and a foxhound.

"Let me introduce you to Pompey," said he. "Pompey is the pride of the local draghounds—no very great flier, as his build will show, but a staunch hound on a scent129. Well, Pompey, you may not be fast, but I expect you will be too fast for a couple of middle-aged130 London gentlemen, so I will take the liberty of fastening this leather leash131 to your collar. Now, boy, come along, and show what you can do." He led him across to the doctor's door. The dog sniffed132 round for an instant, and then with a shrill133 whine134 of excitement started off down the street, tugging135 at his leash in his efforts to go faster. In half an hour, we were clear of the town and hastening down a country road.

"What have you done, Holmes?" I asked.

"A threadbare and venerable device, but useful upon occasion. I walked into the doctor's yard this morning, and shot my syringe full of aniseed over the hind71 wheel. A draghound will follow aniseed from here to John o'Groat's, and our friend, Armstrong, would have to drive through the Cam before he would shake Pompey off his trail. Oh, the cunning rascal136! This is how he gave me the slip the other night."

The dog had suddenly turned out of the main road into a grass-grown lane. Half a mile farther this opened into another broad road, and the trail turned hard to the right in the direction of the town, which we had just quitted. The road took a sweep to the south of the town, and continued in the opposite direction to that in which we started.

"This DETOUR137 has been entirely for our benefit, then?" said Holmes. "No wonder that my inquiries among those villagers led to nothing. The doctor has certainly played the game for all it is worth, and one would like to know the reason for such elaborate deception138. This should be the village of Trumpington to the right of us. And, by Jove! here is the brougham coming round the corner. Quick, Watson—quick, or we are done!"

He sprang through a gate into a field, dragging the reluctant Pompey after him. We had hardly got under the shelter of the hedge when the carriage rattled past. I caught a glimpse of Dr. Armstrong within, his shoulders bowed, his head sunk on his hands, the very image of distress139. I could tell by my companion's graver face that he also had seen.

"I fear there is some dark ending to our quest," said he. "It cannot be long before we know it. Come, Pompey! Ah, it is the cottage in the field!"

There could be no doubt that we had reached the end of our journey. Pompey ran about and whined140 eagerly outside the gate, where the marks of the brougham's wheels were still to be seen. A footpath141 led across to the lonely cottage. Holmes tied the dog to the hedge, and we hastened onward142. My friend knocked at the little rustic door, and knocked again without response. And yet the cottage was not deserted143, for a low sound came to our ears—a kind of drone of misery144 and despair which was indescribably melancholy145. Holmes paused irresolute146, and then he glanced back at the road which he had just traversed. A brougham was coming down it, and there could be no mistaking those gray horses.

"By Jove, the doctor is coming back!" cried Holmes. "That settles it. We are bound to see what it means before he comes."

He opened the door, and we stepped into the hall. The droning sound swelled147 louder upon our ears until it became one long, deep wail148 of distress. It came from upstairs. Holmes darted149 up, and I followed him. He pushed open a half-closed door, and we both stood appalled150 at the sight before us.

A woman, young and beautiful, was lying dead upon the bed. Her calm pale face, with dim, wide-opened blue eyes, looked upward from amid a great tangle151 of golden hair. At the foot of the bed, half sitting, half kneeling, his face buried in the clothes, was a young man, whose frame was racked by his sobs152. So absorbed was he by his bitter grief, that he never looked up until Holmes's hand was on his shoulder.

"Are you Mr. Godfrey Staunton?"

"Yes, yes, I am—but you are too late. She is dead."

The man was so dazed that he could not be made to understand that we were anything but doctors who had been sent to his assistance. Holmes was endeavouring to utter a few words of consolation153 and to explain the alarm which had been caused to his friends by his sudden disappearance when there was a step upon the stairs, and there was the heavy, stern, questioning face of Dr. Armstrong at the door.

"So, gentlemen," said he, "you have attained your end and have certainly chosen a particularly delicate moment for your intrusion. I would not brawl154 in the presence of death, but I can assure you that if I were a younger man your monstrous155 conduct would not pass with impunity156."

"Excuse me, Dr. Armstrong, I think we are a little at cross-purposes," said my friend, with dignity. "If you could step downstairs with us, we may each be able to give some light to the other upon this miserable157 affair."

A minute later, the grim doctor and ourselves were in the sitting-room158 below.

"Well, sir?" said he.

"I wish you to understand, in the first place, that I am not employed by Lord Mount-James, and that my sympathies in this matter are entirely against that nobleman. When a man is lost it is my duty to ascertain his fate, but having done so the matter ends so far as I am concerned, and so long as there is nothing criminal I am much more anxious to hush up private scandals than to give them publicity159. If, as I imagine, there is no breach160 of the law in this matter, you can absolutely depend upon my discretion161 and my cooperation in keeping the facts out of the papers."

Dr. Armstrong took a quick step forward and wrung162 Holmes by the hand.

"You are a good fellow," said he. "I had misjudged you. I thank heaven that my compunction at leaving poor Staunton all alone in this plight163 caused me to turn my carriage back and so to make your acquaintance. Knowing as much as you do, the situation is very easily explained. A year ago Godfrey Staunton lodged164 in London for a time and became passionately165 attached to his landlady's daughter, whom he married. She was as good as she was beautiful and as intelligent as she was good. No man need be ashamed of such a wife. But Godfrey was the heir to this crabbed166 old nobleman, and it was quite certain that the news of his marriage would have been the end of his inheritance. I knew the lad well, and I loved him for his many excellent qualities. I did all I could to help him to keep things straight. We did our very best to keep the thing from everyone, for, when once such a whisper gets about, it is not long before everyone has heard it. Thanks to this lonely cottage and his own discretion, Godfrey has up to now succeeded. Their secret was known to no one save to me and to one excellent servant, who has at present gone for assistance to Trumpington. But at last there came a terrible blow in the shape of dangerous illness to his wife. It was consumption of the most virulent167 kind. The poor boy was half crazed with grief, and yet he had to go to London to play this match, for he could not get out of it without explanations which would expose his secret. I tried to cheer him up by wire, and he sent me one in reply, imploring168 me to do all I could. This was the telegram which you appear in some inexplicable169 way to have seen. I did not tell him how urgent the danger was, for I knew that he could do no good here, but I sent the truth to the girl's father, and he very injudiciously communicated it to Godfrey. The result was that he came straight away in a state bordering on frenzy170, and has remained in the same state, kneeling at the end of her bed, until this morning death put an end to her sufferings. That is all, Mr. Holmes, and I am sure that I can rely upon your discretion and that of your friend."

Holmes grasped the doctor's hand.

"Come, Watson," said he, and we passed from that house of grief into the pale sunlight of the winter day.

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

weird

|

|

| adj.古怪的,离奇的;怪诞的,神秘而可怕的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

baker

|

|

| n.面包师 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

strand

|

|

| vt.使(船)搁浅,使(某人)困于(某地) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

considerably

|

|

| adv.极大地;相当大地;在很大程度上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

insignificant

|

|

| adj.无关紧要的,可忽略的,无意义的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

stagnant

|

|

| adj.不流动的,停滞的,不景气的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

dread

|

|

| vt.担忧,忧虑;惧怕,不敢;n.担忧,畏惧 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

mania

|

|

| n.疯狂;躁狂症,狂热,癖好 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

craved

|

|

| 渴望,热望( crave的过去式 ); 恳求,请求 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

stimulus

|

|

| n.刺激,刺激物,促进因素,引起兴奋的事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

drawn

|

|

| v.拖,拉,拔出;adj.憔悴的,紧张的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

ascetic

|

|

| adj.禁欲的;严肃的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

peril

|

|

| n.(严重的)危险;危险的事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

tempestuous

|

|

| adj.狂暴的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

doorway

|

|

| n.门口,(喻)入门;门路,途径 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

comely

|

|

| adj.漂亮的,合宜的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

inspector

|

|

| n.检查员,监察员,视察员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

dribbling

|

|

| n.(燃料或油从系统内)漏泄v.流口水( dribble的现在分词 );(使液体)滴下或作细流;运球,带球 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

judgment

|

|

| n.审判;判断力,识别力,看法,意见 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

sprint

|

|

| n.短距离赛跑;vi. 奋力而跑,冲刺;vt.全速跑过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

Oxford

|

|

| n.牛津(英国城市) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

romp

|

|

| n.欢闹;v.嬉闹玩笑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

forth

|

|

| adv.向前;向外,往外 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

vigour

|

|

| (=vigor)n.智力,体力,精力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

brawny

|

|

| adj.强壮的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

varied

|

|

| adj.多样的,多变化的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

naive

|

|

| adj.幼稚的,轻信的;天真的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

astonishment

|

|

| n.惊奇,惊异 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

ramifications

|

|

| n.结果,后果( ramification的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

narrative

|

|

| n.叙述,故事;adj.叙事的,故事体的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

marrow

|

|

| n.骨髓;精华;活力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

ascertain

|

|

| vt.发现,确定,查明,弄清 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

orphan

|

|

| n.孤儿;adj.无父母的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

knuckles

|

|

| n.(指人)指关节( knuckle的名词复数 );(指动物)膝关节,踝v.(指人)指关节( knuckle的第三人称单数 );(指动物)膝关节,踝 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

miser

|

|

| n.守财奴,吝啬鬼 (adj.miserly) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

motive

|

|

| n.动机,目的;adv.发动的,运动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

agitation

|

|

| n.搅动;搅拌;鼓动,煽动 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

humble

|

|

| adj.谦卑的,恭顺的;地位低下的;v.降低,贬低 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

agitated

|

|

| adj.被鼓动的,不安的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

crammed

|

|

| adj.塞满的,挤满的;大口地吃;快速贪婪地吃v.把…塞满;填入;临时抱佛脚( cram的过去式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

distinguished

|

|

| adj.卓越的,杰出的,著名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

standing

|

|

| n.持续,地位;adj.永久的,不动的,直立的,不流动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

shrug

|

|

| v.耸肩(表示怀疑、冷漠、不知等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

quill

|

|

| n.羽毛管;v.给(织物或衣服)作皱褶 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

hieroglyphic

|

|

| n.象形文字 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

disappearance

|

|

| n.消失,消散,失踪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

inquiry

|

|

| n.打听,询问,调查,查问 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

counterfoil

|

|

| n.(支票、邮局汇款单、收据等的)存根,票根 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

delicacy

|

|

| n.精致,细微,微妙,精良;美味,佳肴 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

finesse

|

|

| n.精密技巧,灵巧,手腕 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

attain

|

|

| vt.达到,获得,完成 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

attained

|

|

| (通常经过努力)实现( attain的过去式和过去分词 ); 达到; 获得; 达到(某年龄、水平、状况) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

darting

|

|

| v.投掷,投射( dart的现在分词 );向前冲,飞奔 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

penetrating

|

|

| adj.(声音)响亮的,尖锐的adj.(气味)刺激的adj.(思想)敏锐的,有洞察力的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

hack

|

|

| n.劈,砍,出租马车;v.劈,砍,干咳 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

assent

|

|

| v.批准,认可;n.批准,认可 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

twitching

|

|

| n.颤搐 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

rusty

|

|

| adj.生锈的;锈色的;荒废了的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

rustic

|

|

| adj.乡村的,有乡村特色的;n.乡下人,乡巴佬 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

intensity

|

|

| n.强烈,剧烈;强度;烈度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

strictly

|

|

| adv.严厉地,严格地;严密地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

entirely

|

|

| ad.全部地,完整地;完全地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

mischievous

|

|

| adj.调皮的,恶作剧的,有害的,伤人的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

inhuman

|

|

| adj.残忍的,不人道的,无人性的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

rogues

|

|

| n.流氓( rogue的名词复数 );无赖;调皮捣蛋的人;离群的野兽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

truncated

|

|

| adj.切去顶端的,缩短了的,被删节的v.截面的( truncate的过去式和过去分词 );截头的;缩短了的;截去顶端或末端 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

counterfoils

|

|

| n.(支票、票据等的)存根,票根( counterfoil的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

70

blandest

|

|

| adj.(食物)淡而无味的( bland的最高级 );平和的;温和的;无动于衷的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

71

hind

|

|

| adj.后面的,后部的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

confidentially

|

|

| ad.秘密地,悄悄地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

chuckled

|

|

| 轻声地笑( chuckle的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

investigation

|

|

| n.调查,调查研究 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

rattled

|

|

| 慌乱的,恼火的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

motives

|

|

| n.动机,目的( motive的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

ransom

|

|

| n.赎金,赎身;v.赎回,解救 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

concocted

|

|

| v.将(尤指通常不相配合的)成分混合成某物( concoct的过去式和过去分词 );调制;编造;捏造 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

mansion

|

|

| n.大厦,大楼;宅第 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

mere

|

|

| adj.纯粹的;仅仅,只不过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

granite

|

|

| adj.花岗岩,花岗石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

inflexible

|

|

| adj.不可改变的,不受影响的,不屈服的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

jaw

|

|

| n.颚,颌,说教,流言蜚语;v.喋喋不休,教训 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

dour

|

|

| adj.冷酷的,严厉的;(岩石)嶙峋的;顽强不屈 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

machinery

|

|

| n.(总称)机械,机器;机构 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

pry

|

|

| vi.窥(刺)探,打听;vt.撬动(开,起) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

treatise

|

|

| n.专著;(专题)论文 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

conversing

|

|

| v.交谈,谈话( converse的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

rugged

|

|

| adj.高低不平的,粗糙的,粗壮的,强健的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

hush

|

|

| int.嘘,别出声;n.沉默,静寂;v.使安静 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

culpable

|

|

| adj.有罪的,该受谴责的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

crimson

|

|

| n./adj.深(绯)红色(的);vi.脸变绯红色 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

pompous

|

|

| adj.傲慢的,自大的;夸大的;豪华的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

ushered

|

|

| v.引,领,陪同( usher的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

severely

|

|

| adv.严格地;严厉地;非常恶劣地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

stranded

|

|

| a.搁浅的,进退两难的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

inquiries

|

|

| n.调查( inquiry的名词复数 );疑问;探究;打听 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

lengthy

|

|

| adj.漫长的,冗长的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

proceeding

|

|

| n.行动,进行,(pl.)会议录,学报 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

exhausted

|

|

| adj.极其疲惫的,精疲力尽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

fatigue

|

|

| n.疲劳,劳累 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

philosophic

|

|

| adj.哲学的,贤明的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

awry

|

|

| adj.扭曲的,错的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

radius

|

|

| n.半径,半径范围;有效航程,范围,界限 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

consultant

|

|

| n.顾问;会诊医师,专科医生 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

applied

|

|

| adj.应用的;v.应用,适用 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

innate

|

|

| adj.天生的,固有的,天赋的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

scintillating

|

|

| adj.才气横溢的,闪闪发光的; 闪烁的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

discreet

|

|

| adj.(言行)谨慎的;慎重的;有判断力的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

mortifying

|

|

| adj.抑制的,苦修的v.使受辱( mortify的现在分词 );伤害(人的感情);克制;抑制(肉体、情感等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

sardonic

|

|

| adj.嘲笑的,冷笑的,讥讽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

impede

|

|

| v.妨碍,阻碍,阻止 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

concealment

|

|

| n.隐藏, 掩盖,隐瞒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

outspoken

|

|

| adj.直言无讳的,坦率的,坦白无隐的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

antagonist

|

|

| n.敌人,对抗者,对手 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

acumen

|

|

| n.敏锐,聪明 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

worthy

|

|

| adj.(of)值得的,配得上的;有价值的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

favourable

|

|

| adj.赞成的,称赞的,有利的,良好的,顺利的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

120

destined

|

|

| adj.命中注定的;(for)以…为目的地的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

blues

|

|

| n.抑郁,沮丧;布鲁斯音乐 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

neutralized

|

|

| v.使失效( neutralize的过去式和过去分词 );抵消;中和;使(一个国家)中立化 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

horrified

|

|

| a.(表现出)恐惧的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

scouting

|

|

| 守候活动,童子军的活动 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

125

burrow

|

|

| vt.挖掘(洞穴);钻进;vi.挖洞;翻寻;n.地洞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

126

eminent

|

|

| adj.显赫的,杰出的,有名的,优良的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

127

descended

|

|

| a.为...后裔的,出身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

128

squat

|

|

| v.蹲坐,蹲下;n.蹲下;adj.矮胖的,粗矮的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

129

scent

|

|

| n.气味,香味,香水,线索,嗅觉;v.嗅,发觉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

130

middle-aged

|

|

| adj.中年的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

131

leash

|

|

| n.牵狗的皮带,束缚;v.用皮带系住 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

132

sniffed

|

|

| v.以鼻吸气,嗅,闻( sniff的过去式和过去分词 );抽鼻子(尤指哭泣、患感冒等时出声地用鼻子吸气);抱怨,不以为然地说 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

133

shrill

|

|

| adj.尖声的;刺耳的;v尖叫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

134

whine

|

|

| v.哀号,号哭;n.哀鸣 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

135

tugging

|

|

| n.牵引感v.用力拉,使劲拉,猛扯( tug的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

136

rascal

|

|

| n.流氓;不诚实的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

137

detour

|

|

| n.绕行的路,迂回路;v.迂回,绕道 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

138

deception

|

|

| n.欺骗,欺诈;骗局,诡计 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

139

distress

|

|

| n.苦恼,痛苦,不舒适;不幸;vt.使悲痛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

140

whined

|

|

| v.哀号( whine的过去式和过去分词 );哀诉,诉怨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

141

footpath

|

|

| n.小路,人行道 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

142

onward

|

|

| adj.向前的,前进的;adv.向前,前进,在先 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

143

deserted

|

|

| adj.荒芜的,荒废的,无人的,被遗弃的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

144

misery

|

|

| n.痛苦,苦恼,苦难;悲惨的境遇,贫苦 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

145

melancholy

|

|

| n.忧郁,愁思;adj.令人感伤(沮丧)的,忧郁的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

146

irresolute

|

|

| adj.无决断的,优柔寡断的,踌躇不定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

147

swelled

|

|

| 增强( swell的过去式和过去分词 ); 肿胀; (使)凸出; 充满(激情) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

148

wail

|

|

| vt./vi.大声哀号,恸哭;呼啸,尖啸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

149

darted

|

|

| v.投掷,投射( dart的过去式和过去分词 );向前冲,飞奔 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

150

appalled

|

|

| v.使惊骇,使充满恐惧( appall的过去式和过去分词)adj.惊骇的;丧胆的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

151

tangle

|

|

| n.纠缠;缠结;混乱;v.(使)缠绕;变乱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

152

sobs

|

|

| 啜泣(声),呜咽(声)( sob的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

153

consolation

|

|

| n.安慰,慰问 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

154

brawl

|

|

| n.大声争吵,喧嚷;v.吵架,对骂 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

155

monstrous

|

|

| adj.巨大的;恐怖的;可耻的,丢脸的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

156

impunity

|

|

| n.(惩罚、损失、伤害等的)免除 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

157

miserable

|

|

| adj.悲惨的,痛苦的;可怜的,糟糕的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

158

sitting-room

|

|

| n.(BrE)客厅,起居室 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

159

publicity

|

|

| n.众所周知,闻名;宣传,广告 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

160

breach

|

|

| n.违反,不履行;破裂;vt.冲破,攻破 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

161

discretion

|

|

| n.谨慎;随意处理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

162

wrung

|

|

| 绞( wring的过去式和过去分词 ); 握紧(尤指别人的手); 把(湿衣服)拧干; 绞掉(水) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

163

plight

|

|

| n.困境,境况,誓约,艰难;vt.宣誓,保证,约定 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

164

lodged

|

|

| v.存放( lodge的过去式和过去分词 );暂住;埋入;(权利、权威等)归属 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

165

passionately

|

|

| ad.热烈地,激烈地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

166

crabbed

|

|

| adj.脾气坏的;易怒的;(指字迹)难辨认的;(字迹等)难辨认的v.捕蟹( crab的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

167

virulent

|

|

| adj.有毒的,有恶意的,充满敌意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

168

imploring

|

|

| 恳求的,哀求的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

169

inexplicable

|

|

| adj.无法解释的,难理解的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

170

frenzy

|

|

| n.疯狂,狂热,极度的激动 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |