All things being as ready as it was possible to make them, on the 14th of August, 1779, amid the booming of cannon1 and the waving of flags, the expedition set sail. Very pretty it must have looked, dropping down the roads, as sail after sail was set on the broad yardarms extending above the little commander on the poop deck of the Indiaman, resolutely2 putting his difficulties and trials behind him, and glad to be at last at sea and headed for the enemy. And yet he might well have borne a heavy heart! Only a man of Jones' caliber3 could have faced the possibilities with a particle of equanimity4. By any rule of chance or on any ground of probability the expedition was doomed5 to failure, capture, or destruction. But the personality of Jones, his serene6 and soon-to-be-justified7 confidence in himself, discounted chance and overthrew8 probability. I have noticed it is ever the man with the fewest resources and poorest backing who accomplishes most in the world's battles. The man who has things made easy for him usually "takes it easy," and accomplishes the easy thing or nothing.

The squadron was accompanied by two heavily armed privateers, the Monsieur and the Granvelle, raising the number of vessels9 to seven. The masters of the privateers did not sign the concordat11, but they entered into voluntary association with the others and agreed to abide12 by the orders of Jones--an agreement they broke without hesitation13 in the face of the first prize, which was captured on the 18th of August. The prize was a full-rigged ship, called the Verwagting, mounting fourteen guns and loaded with brandy. The vessel10, a Dutch ship, had been captured by the English, and was therefore a lawful14 prize to the squadron. The captain of the Monsieur, which was the boarding vessel, plundered16 the prize of several valuable articles for his own benefit, manned her, and attempted to dispatch her to Ostend. Jones, however, overhauled17 her, replaced the prize crew by some of his own men, and sent her in under his own orders. The Monsieur and her offended captain thereupon promptly18 deserted19 the squadron in the night.

On the 21st, off the southwest coast of Ireland, they captured a brig, the Mayflower, loaded with butter, which was also manned and sent in. On the 23d they rounded Cape20 Clear, the extreme southwestern point of Ireland. The day being calm, Jones manned his boats and sent them inshore to capture a brigantine. The ship, not having steerage way, began to drift in toward the dangerous shore after the departure of the boats, and it became necessary to haul her head offshore21, for which purpose the captain's barge22 was sent ahead with a towline. As the shades of evening descended23, the crew of the barge, who were apparently25 English, took advantage of the absence of the other boats and the opportunity presented, to cut the towline and desert. As they made for the shore, Mr. Cutting Lunt, third lieutenant26, with four marines, jumped into a small boat remaining, and chased the fugitives28 without orders; but, pursuing them too far from the ship, a fog came down which caused him to lose his bearings, and prevented him from joining the Richard that night.

The crew of a commodore's barge, like the crew of a captain's gig, is usually made up of picked men, and the character of the Richard's crew is well indicated by this desertion. The other boats luckily managed to rejoin the Richard, after succeeding in cutting out the brigantine. The ships beat to and fro off the coast until the next day, when the captains assembled on the Richard. Landais behaved outrageously29 on this occasion. He reproached Jones in the most abusive manner, as if the desertion of the barge and the loss of the two boats was due to negligence30 on his part. One can imagine with what grim silence the irate31 little American listened to the absurd tirade32, and in what strong control he held himself to keep from arresting Landais where he stood. It gives us a vivid picture of the situation of the fleet to find that Jones was actually compelled to consult with his captains and obtain the consent of de Varage before he could order the Cerf to reconnoiter the coast, if possible to find the two boats and their crews.

Thus, as Commodore Mackenzie, himself a naval34 officer, grimly remarks:

"Before giving orders of indispensable necessity, as a superior officer, we find him taking the advice of one captain and obtaining the consent and approbation35 of another."

But we may be sure that it was only dire36 necessity that required such a course of action. Evidently the situation was not to the liking37 of the commodore, but it was one that he could not remedy.

As the Cerf approached the shore to reconnoiter, she hoisted38 the English colors to disguise her nationality, and was seen by Mr. Lunt, who had evidently overtaken the deserters. Mistaking her character, he pulled in toward the shore to escape the fancied danger, and was easily captured by the English with the two boats and their crews. By this unfortunate mishap39 the Richard lost two of her boats, containing an officer and twenty-two men. The Cerf, losing sight of the squadron in the evening, turned tail and went back to France, instead of proceeding40 to the first of the various rendezvous41 which had been agreed upon. The Granvelle, having made a prize on her own account, took advantage of her entirely42 independent position and the fact that she was far away from the Richard to disregard signals and make off with her capture. This reduced the squadron to the Richard, Alliance, Pallas, and Vengeance43. It was Jones' desire to cruise to and fro off the harbor of Limerick to intercept44 the West Indian ships, which, to the number of eight or ten, were daily expected. These vessels, richly laden45, were of great value, and their capture could have easily been effected, but Landais protested vehemently46 against remaining in any one spot. Among other things, the Frenchman was undoubtedly47 a coward, and, of course, by remaining steadily48 in one place opportunities for being overhauled were greatly increased. Jones finally succumbed49 to Landais' entreaties50 and protestations, which were backed up by those of Captains Cottineau and Ricot.

Of course, it is impossible to say how far his authority would have lasted had he peremptorily51 refused to accede52 to their demands, as paper concordats are not very binding53 ties; but he might perhaps have made a more determined54 effort to induce them to carry out his plans and remain with him. To leave the position he had chosen, which presented such opportunities, was undoubtedly an error in judgment55, and Jones tacitly admits it in the following words, written long afterward56:

"Nothing prevented me from pursuing my design but the reproach that would have been cast upon my character as a man of prudence57.[11] It would have been said: 'Was he not forewarned by Captain Cottineau and others?'"

The excuse is as bad as, if not worse than, the decision. But this is almost the only evidence of weakness and irresolution58 which appears in Jones' conduct in all the emergencies in which he was thrown. It is impossible to justify59 this action, but, in view of the circumstances, which we can only imagine and hardly adequately comprehend, we need not censure60 him too greatly for his indecision. In fact, the decision itself was a mistake which the ablest of men might naturally make. The weakness lay in the excuse which he himself offers, and which it pains one to read. In this connection the noble comment of Captain Mahan is interesting:

"The subordination of public enterprises to considerations of personal consequences, even to reputation, is a declension from the noblest in a public man. Not life only, but personal credit, is to be fairly risked for the attainment61 of public ends."

It can not be said that Jones was altogether disinterested62 in his actions. The mere63 common, vulgar, mercenary motives64 were absent from his undertakings65, but it must be admitted that he never lost sight of the results, not only to his country and its success, but to his own reputation as well. If Jones had proceeded in his intention, and Landais had finally deserted him, the results would have been very much better for the cruise--always provided that the Pallas at least remained with the Richard. We shall see later on that all the ships deserted him on one occasion.

On the 26th of August a heavy gale67 blew up from the southwest, and Jones scudded68 before it to the northward69 along the Irish coast. Landais deliberately70 changed the course of the Alliance in the darkness, and, the tiller of the Pallas having been carried away during the night, Jones found himself alone with the Vengeance the next morning. The gale having abated71, these two remaining vessels continued their course in a leisurely72 manner along the Irish coast. On the 31st the Alliance hove in sight, followed by a valuable West Indiaman called the Betsy, mounting twenty-two guns, which she had captured--a sample of what might have resulted if the squadron had stayed off Limerick.

The Pallas having also joined company again, on the 1st of September the Richard brought to the union, a government armed ship of twenty-two guns, bound for Halifax with valuable naval stores. Before boats were called away and the prize taken possession of, with unparalleled insolence73 Landais sent a messenger to Jones asking whether the Alliance should man the prize, in which case he should allow no man from the Richard to board her! With incredible complaisance74 the long-suffering Jones allowed Landais to man this capture also, while he himself received the prisoners on the Richard. These two vessels, in violation75 of Jones' explicit76 orders, were sent in to Bergen, Norway, where they were promptly released by the Danish Government and returned to England on the demand of the British minister. Their value was estimated at forty thousand pounds sterling77. The unwarranted return of the vessels was the foundation of a claim for indemnity78 against Denmark, of which we shall hear later. On the day of the capture Landais disregarded another specific signal from the flagship to chase; instead of doing which, he wore ship and headed directly opposite the direction in which he should have gone. The next morning he again disregarded a signal to come within hail of the Richard, on which occasion he did not even set an answering pennant79.

On September 3d and 4th the squadron captured a brig and two sloops80 off the Shetland Islands. On the evening of this day Jones summoned the captains to the flagship. Landais refused to go, and when de Cottineau tried to persuade him to do so he became violently abusive, and declared that the matters at issue between the commodore and himself were so grave that they could only be settled by a personal meeting on shore, at which one or the other should forfeit82 his life. Fortunately for the peace of mind of the commodore, whose patience had reached the breaking point, the Alliance immediately after parted company, and did not rejoin the command until the 23d of September. If Landais had stayed away altogether, or succeeded in getting himself lost or captured, it would have been a great advantage to the country.

Another gale blew up on the 5th, and heavy weather continued for several days. The little squadron of three vessels labored83 along through the heavy seas to the northward, passed the dangerous Orkneys, doubled the wild Hebrides, rounded the northern extremity84 of Scotland, and on the evening of the 13th approached the east coast near the Cheviot Hills. On the 14th they arrived off the Firth of Forth85, where they were lucky enough to capture one ship and one brigantine loaded with coal. From them they learned that the naval force in the harbor of Leith was inconsiderable, consisting of one twenty-gun sloop81 of war and three or four cutters. Jones immediately conceived the idea of destroying this force, holding the town under his batteries, landing a force of marines, and exacting86 a heavy ransom87 under threat of destruction.

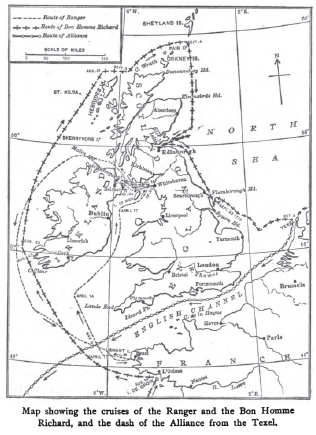

Map showing the cruises of the Ranger88 and the Bon Homme Richard, and the dash of the Alliance from the Texel.

Although weakened in force by the desertion of the ships, by the number of prizes he had manned, and the large number of prisoners on board the Richard, he still hoped, as he says, to teach English cruisers the value of humanity on the other side of the water, and by this bold attack to demonstrate the vulnerability of their own coasts. He also counted upon this diversion in the north to call attention from the expected grand invasion in the south of England by the French and Spanish fleets. The wind was favorable for his design, but unfortunately the Pallas and the Vengeance, which had lagged as usual, were some distance in the offing. Jones therefore ran back to meet them in order to advise them of his plan and concert measures for the attack. He found that the French had but little stomach for the enterprise; they positively89 refused to join him in the undertaking66, a decision which, by the terms of the concordat, they had a right to make. After a night spent in fruitless argument between the three captains--think of it, arguments in the place of orders!--Jones appealed to their cupidity90, probably the last thing that would have moved him. By painting the possibilities of plunder15 he wrung91 a reluctant consent from these two gentlemen, and proceeded rapidly to develop the plan.

As usual, not being able to embrace the opportunity when it was presented, a change in the wind rendered it impossible for the present. The design and opportunity were too good, however, to be lost, and the squadron beat to and fro off the harbor, waiting for a shift of wind to make practicable the effort. On the 15th they captured another collier, a schooner92, the master of which, named Andrew Robertson, was bribed93 by the promised return of his vessel to pilot them into the harbor of Leith. Robertson, a dastardly traitor94, promised to do so, and saved his collier thereby95. On the morning of the 16th an amusing little incident occurred off the coast of Fife. The ships were, of course, sailing under English colors, and one of the seaboard gentry96, taking them for English ships in pursuit of Paul Jones, who was believed to be on the coast, sent a shore boat off to the Richard asking the gift of some powder and shot with which to defend himself in case he received a visit from the dreaded97 pirate. Jones, who was much amused by the situation, made a courteous98 reply to the petition, and sent a barrel of powder, expressing his regret that he had no suitable shot. He detained one of the boatmen, however, as a pilot for one of the other ships. During the interim99 the following proclamation was prepared for issuance when the town had been captured. The document is somewhat diffuse100 in its wording, but the purport101 of it is unmistakable:

"The Honorable J. Paul Jones, Commander-in-chief of the American Squadron, now in Europe, to the Worshipful Provost of Leith, or, in his absence, to the Chief Magistrate102, who is now actually present, and in authority there.

"Sir: The British marine27 force that has been stationed here for the protection of your city and commerce, being now taken by the American arms under my command, I have the honour to send you this summons by my officer, Lieutenant-Colonel de Chamillard, who commands the vanguard of my troops. I do not wish to distress103 the poor inhabitants; my intention is only to demand your contribution toward the reimbursement104 which Britain owes to the much-injured citizens of the United States; for savages105 would blush at the unmanly violation and rapacity106 that have marked the tracks of British tyranny in America, from which neither virgin107 innocence108 nor helpless age has been a plea of protection or pity.

"Leith and its port now lie at our mercy; and, did not our humanity stay the hand of just retaliation109, I should, without advertisement, lay it in ashes. Before I proceed to that stern duty as an officer, my duty as a man induces me to propose to you, by means of a reasonable ransom, to prevent such a scene of horror and distress. For this reason I have authorized110 Lieutenant-Colonel de Chamillard to conclude and agree with you on the terms of ransom, allowing you exactly half an hour's reflection before you finally accept or reject the terms which he shall propose. If you accept the terms offered within the time limited, you may rest assured that no further debarkation111 of troops will be made, but the re-embarkation of the vanguard will immediately follow, and the property of the citizens shall remain unmolested."

On the afternoon of the 16th, the squadron was sighted from Edinburgh Castle, slowly running in toward the Firth. The country had now been fully112 alarmed. It is related that the audacity113 and boldness of this cruise and his previous successes had caused Jones to be regarded with a terror far beyond that which his force justified, and which well-nigh paralyzed resistance. Arms were hastily distributed, however, to the various guilds114, and batteries were improvised115 at Leith. On the 17th, the Richard, putting about, ran down to within a mile of the town of Kirkaldy. As it appeared to the inhabitants that she was about to descend24 upon their coast, they were filled with consternation116. There is a story told that the minister of the place, a quaint117 oddity named Shirra, who was remarkable118 for his eccentricities119, joined his people congregated120 on the beach, surveying the approaching ship in terrified apprehension121, and there made the following prayer:

"Now, deer Lord, dinna ye think it a shame for ye to send this vile122 piret to rob our folk o' Kirkaldy? for ye ken33 they're puir enow already, and hae naething to spaire. The wa the ween blaws, he'll be here in a jiffie, and wha kens123 what he may do? He's nae too guid for onything. Meickle's the mischief124 he has dune125 already. He'll burn thir hooses, tak their very claes and tirl them to the sark; and wae's me! wha kens but the bluidy villain126 might take their lives! The puir weemen are maist frightened out o' their wits, and the bairns skirling after them. I canna thol't it! I canna thol't it! I hae been lang a faithfu' servant to ye, Laird; but gin ye dinna turn the ween about, and blaw the scoundrel out of our gate, I'll na staur a fit, but will just sit here till the tide comes. Sae tak yere will o't."

This extraordinary petition has probably lost nothing by being handed down. At any rate, just as that moment, a squall which had been brewing127 broke violently over the ship, and Jones was compelled to bear up and run before it. The honest people of Kirkaldy always attributed their relief to the direct interposition of Providence128 as the result of the prayer of their minister. He accepted the honors for his Lord and himself by remarking, whenever the subject was mentioned to him, that he had prayed but the Lord had sent the wind!

It is an interesting tale, but its effect is somewhat marred129 when we consider that Jones had no intention of ever landing at Kirkaldy or of doing the town any harm. He was after bigger game, and in his official account he states that he finally succeeded in getting nearly within gunshot distance of Leith, and had made every preparation to land there, when a gale which had been threatening blew so strongly offshore that, after making a desperate attempt to reach an anchorage and wait until it blew itself out, he was obliged to run before it and get to sea. When the gale abated in the evening he was far from the port, which had now become thoroughly130 alarmed. Heavy batteries were thrown up and troops concentrated for its protection, so that he concluded to abandon the attempt. His conception had been bold and brilliant, and his success would have been commensurate if, when the opportunity had presented itself, he had been seconded by men on the other ships with but a tithe131 of his own resolution.

The squadron continued its cruise to the southward and captured several coasting brigs, schooners132, and sloops, mostly laden with coal and lumber133. Baffled in the Forth, Jones next determined upon a similar project in the Tyne or the Humber, and on the 19th of the month endeavored to enlist134 the support of his captains for a descent on Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as it was one of his favorite ideas to cut off the London coal supply by destroying the shipping135 there; but Cottineau, of the Pallas, refused to consent. The ships had been on the coast now for nearly a week, and there was no telling when a pursuing English squadron would make its appearance. Cottineau told de Chamillard that unless Jones left the coast the next day the Richard would be abandoned by the two remaining ships. Jones, therefore, swallowing his disappointment as best be might, made sail for the Humber and the important shipping town of Hull136.

It was growing late in September, and the time set for the return to the Texel was approaching. As a matter of fact, however, though Jones remained on the coast cruising up and down and capturing everything he came in sight of, in spite of his anxiety Cottineau did not actually desert his commodore. Cottineau was the best of the French officers. Without the contagion137 of the others he might have shown himself a faithful subordinate at all times. Having learned the English private signals from a captured vessel, Jones, leaving the Pallas, boldly sailed into the mouth of the Humber, just as a heavy convoy138 under the protection of a frigate139 and a small sloop of war was getting under way to come out of it. Though he set the English flag and the private signals in the hope of decoying the whole force out to sea and under his guns, to his great disappointment the ships, including the war vessels, put back into the harbor. The Richard thereupon turned to the northward and slowly sailed along the coast, followed by the Vengeance.

Early in the morning of September 23d, while it was yet dark, the Richard chased two ships, which the daylight revealed to be the Pallas and the long-missing Alliance, which at last rejoined. The wind was blowing fresh from the southwest, and the two ships under easy canvas slowly rolled along toward Flamborough Head. Late in the morning the Richard discovered a large brigantine inshore and to windward. Jones immediately gave chase to her, when the brigantine changed her course and headed for Bridlington Bay, where she came to anchor.

Bridlington Bay lies just south of Flamborough Head, which is a bold promontory140 bearing a lighthouse and jutting141 far out into the North Sea. Vessels from the north bound for Hull or London generally pass close to the shore at that point, in order to make as little of a detour142 as possible. For this reason Jones had selected it as a particularly good cruising ground. Sheltered from observation from one side or the other, he waited for opportunities, naturally abundant, to pounce143 upon unsuspecting merchant ships. The Baltic fleet had not yet appeared off the coast, though it was about due. Unless warned of his presence, it would inevitably144 pass the bold headland and afford brilliant opportunity for attack. If his unruly consorts145 would only remain with him a little longer something might yet be effected. To go back now would be to confess to a partial failure, and Jones was determined to continue the cruise even alone, until he had demonstrated his fitness for higher things. Fate had his opportunity ready for him, and he made good use of it.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

cannon

|

|

| n.大炮,火炮;飞机上的机关炮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

resolutely

|

|

| adj.坚决地,果断地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

caliber

|

|

| n.能力;水准 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

equanimity

|

|

| n.沉着,镇定 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

doomed

|

|

| 命定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

serene

|

|

| adj. 安详的,宁静的,平静的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

justified

|

|

| a.正当的,有理的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

overthrew

|

|

| overthrow的过去式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

vessels

|

|

| n.血管( vessel的名词复数 );船;容器;(具有特殊品质或接受特殊品质的)人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

vessel

|

|

| n.船舶;容器,器皿;管,导管,血管 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

concordat

|

|

| n.协定;宗派间的协约 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

abide

|

|

| vi.遵守;坚持;vt.忍受 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

hesitation

|

|

| n.犹豫,踌躇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

lawful

|

|

| adj.法律许可的,守法的,合法的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

plunder

|

|

| vt.劫掠财物,掠夺;n.劫掠物,赃物;劫掠 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

plundered

|

|

| 掠夺,抢劫( plunder的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

overhauled

|

|

| v.彻底检查( overhaul的过去式和过去分词 );大修;赶上;超越 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

promptly

|

|

| adv.及时地,敏捷地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

deserted

|

|

| adj.荒芜的,荒废的,无人的,被遗弃的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

cape

|

|

| n.海角,岬;披肩,短披风 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

offshore

|

|

| adj.海面的,吹向海面的;adv.向海面 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

barge

|

|

| n.平底载货船,驳船 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

descended

|

|

| a.为...后裔的,出身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

descend

|

|

| vt./vi.传下来,下来,下降 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

apparently

|

|

| adv.显然地;表面上,似乎 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

lieutenant

|

|

| n.陆军中尉,海军上尉;代理官员,副职官员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

marine

|

|

| adj.海的;海生的;航海的;海事的;n.水兵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

fugitives

|

|

| n.亡命者,逃命者( fugitive的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

outrageously

|

|

| 凶残地; 肆无忌惮地; 令人不能容忍地; 不寻常地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

negligence

|

|

| n.疏忽,玩忽,粗心大意 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

irate

|

|

| adj.发怒的,生气 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

tirade

|

|

| n.冗长的攻击性演说 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

ken

|

|

| n.视野,知识领域 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

naval

|

|

| adj.海军的,军舰的,船的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

approbation

|

|

| n.称赞;认可 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

dire

|

|

| adj.可怕的,悲惨的,阴惨的,极端的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

liking

|

|

| n.爱好;嗜好;喜欢 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

hoisted

|

|

| 把…吊起,升起( hoist的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

mishap

|

|

| n.不幸的事,不幸;灾祸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

proceeding

|

|

| n.行动,进行,(pl.)会议录,学报 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

rendezvous

|

|

| n.约会,约会地点,汇合点;vi.汇合,集合;vt.使汇合,使在汇合地点相遇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

entirely

|

|

| ad.全部地,完整地;完全地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

vengeance

|

|

| n.报复,报仇,复仇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

intercept

|

|

| vt.拦截,截住,截击 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

laden

|

|

| adj.装满了的;充满了的;负了重担的;苦恼的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

vehemently

|

|

| adv. 热烈地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

steadily

|

|

| adv.稳定地;不变地;持续地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

succumbed

|

|

| 不再抵抗(诱惑、疾病、攻击等)( succumb的过去式和过去分词 ); 屈从; 被压垮; 死 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

entreaties

|

|

| n.恳求,乞求( entreaty的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

peremptorily

|

|

| adv.紧急地,不容分说地,专横地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

accede

|

|

| v.应允,同意 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

binding

|

|

| 有约束力的,有效的,应遵守的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

determined

|

|

| adj.坚定的;有决心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

judgment

|

|

| n.审判;判断力,识别力,看法,意见 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

afterward

|

|

| adv.后来;以后 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

prudence

|

|

| n.谨慎,精明,节俭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

irresolution

|

|

| n.不决断,优柔寡断,犹豫不定 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

justify

|

|

| vt.证明…正当(或有理),为…辩护 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

censure

|

|

| v./n.责备;非难;责难 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

attainment

|

|

| n.达到,到达;[常pl.]成就,造诣 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

disinterested

|

|

| adj.不关心的,不感兴趣的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

mere

|

|

| adj.纯粹的;仅仅,只不过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

motives

|

|

| n.动机,目的( motive的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

undertakings

|

|

| 企业( undertaking的名词复数 ); 保证; 殡仪业; 任务 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

undertaking

|

|

| n.保证,许诺,事业 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

gale

|

|

| n.大风,强风,一阵闹声(尤指笑声等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

scudded

|

|

| v.(尤指船、舰或云彩)笔直、高速而平稳地移动( scud的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

northward

|

|

| adv.向北;n.北方的地区 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

deliberately

|

|

| adv.审慎地;蓄意地;故意地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

abated

|

|

| 减少( abate的过去式和过去分词 ); 减去; 降价; 撤消(诉讼) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

leisurely

|

|

| adj.悠闲的;从容的,慢慢的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

insolence

|

|

| n.傲慢;无礼;厚颜;傲慢的态度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

complaisance

|

|

| n.彬彬有礼,殷勤,柔顺 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

violation

|

|

| n.违反(行为),违背(行为),侵犯 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

explicit

|

|

| adj.详述的,明确的;坦率的;显然的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

sterling

|

|

| adj.英币的(纯粹的,货真价实的);n.英国货币(英镑) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

indemnity

|

|

| n.赔偿,赔款,补偿金 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

pennant

|

|

| n.三角旗;锦标旗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

sloops

|

|

| n.单桅纵帆船( sloop的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

81

sloop

|

|

| n.单桅帆船 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

forfeit

|

|

| vt.丧失;n.罚金,罚款,没收物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

labored

|

|

| adj.吃力的,谨慎的v.努力争取(for)( labor的过去式和过去分词 );苦干;详细分析;(指引擎)缓慢而困难地运转 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

extremity

|

|

| n.末端,尽头;尽力;终极;极度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

forth

|

|

| adv.向前;向外,往外 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

exacting

|

|

| adj.苛求的,要求严格的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

ransom

|

|

| n.赎金,赎身;v.赎回,解救 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

ranger

|

|

| n.国家公园管理员,护林员;骑兵巡逻队员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

positively

|

|

| adv.明确地,断然,坚决地;实在,确实 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

cupidity

|

|

| n.贪心,贪财 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

wrung

|

|

| 绞( wring的过去式和过去分词 ); 握紧(尤指别人的手); 把(湿衣服)拧干; 绞掉(水) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

schooner

|

|

| n.纵帆船 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

bribed

|

|

| v.贿赂( bribe的过去式和过去分词 );向(某人)行贿,贿赂 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

traitor

|

|

| n.叛徒,卖国贼 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

thereby

|

|

| adv.因此,从而 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

gentry

|

|

| n.绅士阶级,上层阶级 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

dreaded

|

|

| adj.令人畏惧的;害怕的v.害怕,恐惧,担心( dread的过去式和过去分词) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

courteous

|

|

| adj.彬彬有礼的,客气的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

interim

|

|

| adj.暂时的,临时的;n.间歇,过渡期间 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

diffuse

|

|

| v.扩散;传播;adj.冗长的;四散的,弥漫的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

purport

|

|

| n.意义,要旨,大要;v.意味著,做为...要旨,要领是... | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

magistrate

|

|

| n.地方行政官,地方法官,治安官 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

distress

|

|

| n.苦恼,痛苦,不舒适;不幸;vt.使悲痛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

reimbursement

|

|

| n.偿还,退还 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

savages

|

|

| 未开化的人,野蛮人( savage的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

rapacity

|

|

| n.贪婪,贪心,劫掠的欲望 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

virgin

|

|

| n.处女,未婚女子;adj.未经使用的;未经开发的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

innocence

|

|

| n.无罪;天真;无害 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

retaliation

|

|

| n.报复,反击 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

authorized

|

|

| a.委任的,许可的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

debarkation

|

|

| n.下车,下船,登陆 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

fully

|

|

| adv.完全地,全部地,彻底地;充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

audacity

|

|

| n.大胆,卤莽,无礼 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

guilds

|

|

| 行会,同业公会,协会( guild的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

improvised

|

|

| a.即席而作的,即兴的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

consternation

|

|

| n.大为吃惊,惊骇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

quaint

|

|

| adj.古雅的,离奇有趣的,奇怪的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

eccentricities

|

|

| n.古怪行为( eccentricity的名词复数 );反常;怪癖 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

120

congregated

|

|

| (使)集合,聚集( congregate的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

apprehension

|

|

| n.理解,领悟;逮捕,拘捕;忧虑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

vile

|

|

| adj.卑鄙的,可耻的,邪恶的;坏透的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

kens

|

|

| vt.知道(ken的第三人称单数形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

mischief

|

|

| n.损害,伤害,危害;恶作剧,捣蛋,胡闹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

125

dune

|

|

| n.(由风吹积而成的)沙丘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

126

villain

|

|

| n.反派演员,反面人物;恶棍;问题的起因 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

127

brewing

|

|

| n. 酿造, 一次酿造的量 动词brew的现在分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

128

providence

|

|

| n.深谋远虑,天道,天意;远见;节约;上帝 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

129

marred

|

|

| adj. 被损毁, 污损的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

130

thoroughly

|

|

| adv.完全地,彻底地,十足地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

131

tithe

|

|

| n.十分之一税;v.课什一税,缴什一税 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

132

schooners

|

|

| n.(有两个以上桅杆的)纵帆船( schooner的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

133

lumber

|

|

| n.木材,木料;v.以破旧东西堆满;伐木;笨重移动 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

134

enlist

|

|

| vt.谋取(支持等),赢得;征募;vi.入伍 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

135

shipping

|

|

| n.船运(发货,运输,乘船) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

136

hull

|

|

| n.船身;(果、实等的)外壳;vt.去(谷物等)壳 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

137

contagion

|

|

| n.(通过接触的疾病)传染;蔓延 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

138

convoy

|

|

| vt.护送,护卫,护航;n.护送;护送队 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

139

frigate

|

|

| n.护航舰,大型驱逐舰 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

140

promontory

|

|

| n.海角;岬 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

141

jutting

|

|

| v.(使)突出( jut的现在分词 );伸出;(从…)突出;高出 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

142

detour

|

|

| n.绕行的路,迂回路;v.迂回,绕道 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

143

pounce

|

|

| n.猛扑;v.猛扑,突然袭击,欣然同意 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

144

inevitably

|

|

| adv.不可避免地;必然发生地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

145

consorts

|

|

| n.配偶( consort的名词复数 );(演奏古典音乐的)一组乐师;一组古典乐器;一起v.结伴( consort的第三人称单数 );交往;相称;调和 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |