This ceremony, which originated more than 2000 years ago, had been discontinued by degenerate5 princes, but was revived by Yong-tching, the third of the Mantchoo dynasty. This anniversary takes place on the 24th day of the second moon, coinciding with our month of February. The monarch6 prepares himself for it by fasting three days; he then repairs to the appointed spot with three princes, nine presidents of the high tribunals, forty old and forty young husbandmen. Having performed a preliminary sacrifice of the fruits of the earth to Shang-ti, the supreme7 deity8, he takes in his hand the plough, and makes a furrow9 of some length, in which he is followed by the princes and other grandees10. A similar course is observed in sowing the field, and the operations are completed by the husbandmen.

57

An annual festival in honour of Agriculture is also celebrated11 in the capital of each province. The governor marches forth12, crowned with flowers, and accompanied by a numerous train, bearing flags adorned13 with agricultural emblems14 and portraits of eminent15 husbandmen, while the streets are decorated with lanterns and triumphal arches.

Although rice is the staple16 grain in use in China, wheat-growing is one of the principal industries in the northern and middle parts of that country. The winter wheat is planted at about the same time that wheat is planted here. The soil, especially in the northern provinces, is so well worn that it is unfitted for wheat-growing, and the Chinese farmers, appreciating this fact, and the fact that all kinds of fertilisers are excessively dear, make the least money do the most good by mixing the seed with finely-prepared manure17.

A man with a basket swung upon his shoulders follows the plough, and plants the mixture in large handsful in the furrows18, so that when the crop grows up it looks like young celery. Immediately after the first melting of snow, and when the ground has become sufficiently19 hardened by frost, these wheat-fields are turned into pastures, under the theory that, by a timely clipping of the tops of these plants, the crops will grow up with additional strength in the spring.

Wheat-threshing is the principal interest in Chinese farming. Owing to the scarcity20 of fuel, the wheat is usually pulled up by the root, bundled in sheaves, and carted to the mien-chong, a smooth and hardened58 space of ground near the home of the farmer. The top of the sheaves is then clipped off by a hand machine. The wheat is then left in the mien-chong to dry, whilst the headless sheaves are piled in a heap for fuel or thatching. When the wheat is thoroughly21 dry it is beaten under a great stone roller pulled by horses, while the places thus rolled are constantly tossed over with pitchforks. The stalks left untouched by the roller are threshed with flails22 by women and boys. The beaten stalks and straws are then taken out by an ingenious arrangement of pitchforks, and the chaff23 is removed by a systematic24 tossing of the grain into the air until the wind blows every particle of chaff or dust out of the wheat. Even the chaff is carefully swept up and stowed away for fuel or other useful purposes, such as stuffing mattresses25 or pillows. After the wheat is allowed to dry for a few hours in the burning sun, it is stowed away in airy bamboo bins26.

The milling process is a very ancient one. Two large round bluestone wheels, with grooves27 neatly28 cut in the faces on one side, and in the centre of the lower wheel a solid wooden plug is used. The process of making flour out of wheat by this machinery29 is called mob-mien. Usually a horse or mule30 is employed; the poor, having no animals, grind the grain themselves.

Three distinct qualities of flour are thus produced. The shon-mien, or A grade, is the first siftings; the nee-mien, or second grade, is the grindings of the rough leavings from the first siftings, which is of a darker and redder colour than the first grade; and mod is the finely-ground last siftings of all grades.59 When bread is made from this grade it resembles rough gingerbread. This is usually the food of the poorest families. The bread of the Chinese is usually fermented33, and then steamed. Only a very small quantity is baked in ovens. But the staple articles of food in Northern China are wheat, millet34, and sweet potatoes. Wheat and rice are the food of the rich, while the middle classes of the Empire eat millet and rice. In the southern provinces the entire bread-stuff is rice.

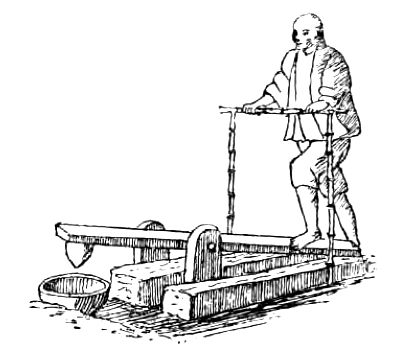

Chinese Method of Husking Grain.

At King-Kiang wheat is served as rice. It is first threshed with flails made of bamboo, and then pounded by a rough stone hammer, working in a mortar35 which rests on a pivot36, and is operated like a treadle by the human foot. This separates the husks, and it is then winnowed37, the grain being afterwards ground in the usual way.

60

Rice is undoubtedly38 the staple food of those parts of China where it will grow, in spite of its being a precarious39 crop, the failure of which means famine. A drought in its early stages withers40 it, and an inundation41, when nearly ripe, is equally destructive; whilst the birds and locusts42, which are fearfully numerous in China, infest43 it more than any other grain. Rice requires not only intense heat, but moisture so abundant that the field in which it grows must be repeatedly laid under water. These requisites44 exist only in the districts south of the Yang-tse Kiang (the Yellow River) and its several tributaries45. Here a vast extent of land is perfectly46 fitted for this valuable crop. Confined by powerful dykes47, these rivers do not generally, like the Nile, overflow48 and cover the country; but by means of canals their waters are so widely distributed that almost every farmer, when he pleases, can inundate49 his field. This supplies not only moisture, but a fertilising mud or slime, washed down from the distant mountains. The cultivator thus dispenses50 with manure, of which he labours under a great scarcity, and considers it enough if the grain be steeped in liquid manure.

The Chinese always transplant their rice. A small space is enclosed, and very thickly sown, after which a thin sheet of water is led or pumped over it; in the course of a few days the shoots appear, and when they have attained51 the height of six or seven inches the tops are cut off, and the roots transplanted to a field prepared for the purpose, when they are set in rows about six inches from each other. The whole61 surface is again supplied with moisture, which continues to cover the plants till they approach maturity52, when the ground is allowed to become dry.

The first harvest is reaped in the end of May or beginning of June, the grain being cut with a small sickle53, and carried off the field in frames suspended from bamboo poles placed across a man’s shoulders. Barrow (p. 565) thus describes one: ‘The machine usually employed for clearing rice from the husk, in the large way, is exactly the same as that now used in Egypt for the same purpose, only that the latter is put in motion by oxen and the former commonly by water. This machine consists of a long horizontal axis54 of wood, with cogs, or projecting pieces of wood or iron, fixed55 upon it at certain intervals56, and it is turned by a water-wheel. At right angles to this axis are fixed as many horizontal levers as there are circular rows of cogs; these levers act on pivots57 that are fastened into a low brick wall, but parallel to the axis and at the distance of about two feet from it. At the further extremity58 of each lever, and perpendicular59 to it, is fixed a hollow pestle60, directly over a large mortar of stone or iron sunk into the ground; the other extremity extending beyond the wall, being pressed upon by the cogs of the axis in its rotation61, elevates the pestle, which by its own gravity falls into the mortar. An axis of this kind sometimes gives motion to 15 or 20 levers.’

Meantime the stubble is burnt on the land, over which the ashes are spread as its only manure; a second crop is immediately sown, and reaped about the end of October, when the straw is left to putrify62 on the ground, which is allowed to rest till the commencement of the ensuing spring.

As the cereal food of the Chinese is principally boiled rice, it stands to reason that bakers63 are not numerous, bread only appearing at the tables of high-class mandarins. It is chiefly replaced by fancy biscuits and numberless kinds of pastry64, made not only with wheaten flour, but also that of rice—these serve as vehicles for the various jams and fruit compotes for which the Chinese are famous, and which they know so well how to make; in fact, the bakers are more strictly65 confectioners, and they can be seen any day busy in their shops baking cakes of rice flour and ground almonds of every imaginable shape and varied66 in quality by spices. Not only so, but these cakes are sold, already baked, in the peripatetic67 cookeries which go about the streets. Out of wheaten flour they make a kind of vermicelli, which is much esteemed68 by the Chinese.

Failure of the rice crops, and consequent famine in Japan, have been the means of introducing wheaten flour into this country more rapidly than anything else could have done. Most remarkable69 is the universal favour that bread and similar floury concoctions70 are beginning to enjoy in the treaty ports. This article of food has become completely Japanized, and sells in forms unknown to Europeans. Tsuke-pau, sold by peripatetic vendors71, who push their wares72 along in a tiny roofed hand-cart, is much liked by the poorer classes. It consists of slices—thick, generous slices—of bread dipped in soy and brown sugar, and then fried or toasted. Each slice has a skewer73 passed63 through it, which the buyer returns after demolishing74 the bread.

Flour is now used in many other ways besides the manufacture of simple bread. There is Kash-pau, cake bread, which is sold everywhere. As the name implies, it is a sort of sweet breadstuff made into cakes of various sizes and artistic75 figures, according to the skill and fancy of the baker62. To an European palate this Kash-pau is rather dry and tasteless, but it is very cheap, and for five sen (three-halfpence) a huge paper bagful can be bought. Kasuteira, or sponge cake, is not so much sought after as it used to be. Yet some bakeries, such as the Fugetsu-do and Tsuboya, excel in producing the lightest and most delicious sponge cake.

Millet, in China, is only used as food by the very poor.

Wheat is not the primary article of food among the natives of India, and hitherto only enough has been produced for home consumption; but of late years much has been grown for export, and being of a particularly hard nature is useful for mixing with the softer kinds. Still, it is used by itself, and is made into unleavened cakes called Chupatees. These are made by mixing flour and water together, with a little salt, into a paste or dough76, kneading it well; sometimes ghee (clarified butter) is added. They may also be made with milk instead of water. They are flattened77 into thin cakes with the hand, smeared78 with a small quantity of ghee, and baked on an iron pan, or sheet of iron, over the fire.

Historic, too, is the Chupatee, for by its means the64 message was sent round throughout the length and breadth of British India for the rising against the English rule—known as the Indian Mutiny. Its true meaning was not at first understood, as we may read in the Indian correspondence of the Times, dated Bombay, March 3, 1857: ‘From Cawnpore to Allahabad, and onwards towards the great cities of the North-West, the chokedars, or policemen, have been of late spreading from village to village—at whose command, or for what object, they themselves, it is said, are ignorant—little plain cakes of wheaten flour. The number of cakes, and the mode of their transmission, is uniform. Chokedar of village A enters village B, and, addressing its chokedar, commits to his charge two cakes, with directions to have other two similar to them prepared; and, leaving the old in his own village, to hie with the new to village C, and so on. English authorities of the districts through which these edibles79 passed looked at, handled, and probably tasted them; and finding them, upon the evidence of all their senses, harmless, reported accordingly to the Government. And it appears, I think, with tolerable clearness, that the mysterious mission is not of political but of superstitious80 origin; and is directed simply to the warding82 off of diseases, such as the choleraic visitation of twelve months ago, in which point of view it is noteworthy and characteristic, and not unworthy to be remembered together with last year’s grim and picturesque83 legend of the horseman, who rode down to the river at dead of night and was ferried across, announcing that the pestilence84 was in his train.’

65

Apropos85 of Indian flour, Col. Meadows Taylor, in The Story of My Life, tells a story anent the adulteration of flour in India.

‘During that day my tent was beset86 by hundreds of pilgrims and travellers, crying loudly for justice against the flour-sellers, who not only gave short weight in flour, but adulterated it so distressingly87 with sand that the cakes made with it were uneatable, and had to be thrown away. That evening I told some reliable men of my escort to go quietly into the bazaars88 and each buy flour at a separate shop, being careful to note whose shop it was.

‘The flour was brought to me. I tested every sample, and found it full of sand as I passed it under my teeth. I then desired that all the persons named in my list should be sent to me with their baskets of flour, their weights and scales. Shortly afterwards they arrived, evidently suspecting nothing, and were placed in a row seated on the grass before my tent.

‘“Now,” said I gravely, “each of you is to weigh out a ser (two pounds) of your flour,” which was done. “Is it for the pilgrims?” asked one.

‘“No,” said I quietly, though I had much difficulty to keep my countenance89. “You must eat it yourselves.”

‘They saw that I was in earnest, and offered to pay any fine that I imposed.

‘“Not so,” I returned, “you have made many eat your flour; why should you object to eat it yourselves?”

‘They were horribly frightened, and, amid the jeers90 and screams of laughter of the bystanders, some of them actually began to eat, spluttering out the66 half-moistened flour, which could be heard crunching91 between their teeth. At last some of them flung themselves on their faces, abjectly92 beseeching93 pardon.

‘“Swear!” I cried, “swear by the Holy Mother in yonder temple that you will not fill the mouths of her worshippers with dirt! You have brought this on yourselves, and there is not a man in all the country who will not laugh at the bunnais (flour-sellers) who could not eat their own flour because it broke their teeth.”

‘So this episode terminated, and I heard no more complaints of bad flour.’

The Indian flour mill is very primitive94, consisting of two great mill-stones, of which the lower is fast, and the upper is usually turned by two women, who feed the wheat by handfuls into a hole which passes through the stone. The meal so obtained is simply mixed with palm yeast95, and baked in very hot ovens, which have been heated for several days. The small European householder finds it more convenient to patronise the Mohammedan bakers, of whom, however, the bread has to be ordered in advance. Sometimes two or three English families combine, and hire a baker, paying him a monthly salary, and providing him with the raw material.

The yeast mentioned above is made from the sap of the date palm. In April, before the flowers appear, a Hindoo climbs the naked trunk—for the leaves, as in all palm trees, are borne on the top. The man’s feet are bound together by a rope, and about his hips96 are fastened two pots for the reception of the sap. 67As he climbs, he calls out, ‘Darpor, darpor ata hain,’ which, being interpreted, means, ‘The palm-tapper is coming.’ This is for the benefit of the Mohammedan women who might be sitting unveiled in the courtyards of the houses exposed to the view of the climber after he has risen above the tops of the walls. A tapper who once fails to give this warning cry is thenceforth forbidden to ply81 his trade. When the tapper has reached the crown of the tree he cuts two gashes97 in opposite sides of the trunk with an axe98, which he has carried up in his mouth. Then he fastens the pots under the gashes and descends99. The full pots are taken away and empty ones put in their place twice daily. The sap has a sweet taste, and contains some alcohol even when fresh. After standing100 in the sun in great earthen pots for a few days it begins to ferment32, after which it deposits a thick white substance. This, taken at the proper time, is used as yeast.

But rice is, in India, the staff of life, being used to a greater extent than any grain in Europe. It is, in fact, the food of the highest and the lowest, the principal harvest of every climate. Its production, generally speaking, is only limited by the means of irrigation, which is essential to its growth. The ground is prepared in March and April; the seed is sown in May and reaped in August. If circumstances are favourable101 there are other harvests, one between July and November, another between January and April. These also sometimes consist of rice, but more commonly of other grain or pulse. In some parts millet is used as food. Many are the ways of cooking rice—there are powder of cucumber seeds and68 rice, lime juice and rice, orange juice and rice, jack102 fruit and rice, rice and milk, and sweet cakes made of rice flour, with or without green ginger31.

The Bombay baker is a man of a different stamp altogether to the Bengal baker. He is invariably a Goanese and a native Christian103, and adopts his profession not from choice but by heredity. For generations past his fathers have been bakers, and have, in accordance with the rules of the Society of Bakers, to which they must have belonged, studied some portion at least of the art of manufacturing bread. The Bombay baker is, moreover, a man of substance. To begin with, he grows his own wheat, and has it conveyed to his factories, where as many as 200 hands are employed in converting it into raw material for cooking. He retains a staff of chefs, who also hail from Goa, and who attend exclusively to the baking. Greater comparative intelligence and a love for his trade enable him to turn out a far superior article to that of his ignorant contemporary in Upper India; but even in Bombay the same fault has to be found with the manufacturer: either the bread is too fine, or it is too ‘brown’—that is, it contains too much bran.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

veneration

|

|

| n.尊敬,崇拜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

inscribed

|

|

| v.写,刻( inscribe的过去式和过去分词 );内接 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

homage

|

|

| n.尊敬,敬意,崇敬 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

annually

|

|

| adv.一年一次,每年 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

degenerate

|

|

| v.退步,堕落;adj.退步的,堕落的;n.堕落者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

monarch

|

|

| n.帝王,君主,最高统治者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

supreme

|

|

| adj.极度的,最重要的;至高的,最高的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

deity

|

|

| n.神,神性;被奉若神明的人(或物) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

furrow

|

|

| n.沟;垄沟;轨迹;车辙;皱纹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

grandees

|

|

| n.贵族,大公,显贵者( grandee的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

celebrated

|

|

| adj.有名的,声誉卓著的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

forth

|

|

| adv.向前;向外,往外 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

adorned

|

|

| [计]被修饰的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

emblems

|

|

| n.象征,标记( emblem的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

eminent

|

|

| adj.显赫的,杰出的,有名的,优良的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

staple

|

|

| n.主要产物,常用品,主要要素,原料,订书钉,钩环;adj.主要的,重要的;vt.分类 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

manure

|

|

| n.粪,肥,肥粒;vt.施肥 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

furrows

|

|

| n.犁沟( furrow的名词复数 );(脸上的)皱纹v.犁田,开沟( furrow的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

scarcity

|

|

| n.缺乏,不足,萧条 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

thoroughly

|

|

| adv.完全地,彻底地,十足地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

flails

|

|

| v.鞭打( flail的第三人称单数 );用连枷脱粒;(臂或腿)无法控制地乱动;扫雷坦克 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

chaff

|

|

| v.取笑,嘲笑;n.谷壳 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

systematic

|

|

| adj.有系统的,有计划的,有方法的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

mattresses

|

|

| 褥垫,床垫( mattress的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

bins

|

|

| n.大储藏箱( bin的名词复数 );宽口箱(如面包箱,垃圾箱等)v.扔掉,丢弃( bin的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

grooves

|

|

| n.沟( groove的名词复数 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏v.沟( groove的第三人称单数 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

neatly

|

|

| adv.整洁地,干净地,灵巧地,熟练地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

machinery

|

|

| n.(总称)机械,机器;机构 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

mule

|

|

| n.骡子,杂种,执拗的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

ginger

|

|

| n.姜,精力,淡赤黄色;adj.淡赤黄色的;vt.使活泼,使有生气 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

ferment

|

|

| vt.使发酵;n./vt.(使)激动,(使)动乱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

fermented

|

|

| v.(使)发酵( ferment的过去式和过去分词 );(使)激动;骚动;骚扰 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

millet

|

|

| n.小米,谷子 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

mortar

|

|

| n.灰浆,灰泥;迫击炮;v.把…用灰浆涂接合 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

pivot

|

|

| v.在枢轴上转动;装枢轴,枢轴;adj.枢轴的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

winnowed

|

|

| adj.扬净的,风选的v.扬( winnow的过去式和过去分词 );辨别;选择;除去 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

precarious

|

|

| adj.不安定的,靠不住的;根据不足的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

withers

|

|

| 马肩隆 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

inundation

|

|

| n.the act or fact of overflowing | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

locusts

|

|

| n.蝗虫( locust的名词复数 );贪吃的人;破坏者;槐树 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

infest

|

|

| v.大批出没于;侵扰;寄生于 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

requisites

|

|

| n.必要的事物( requisite的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

tributaries

|

|

| n. 支流 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

dykes

|

|

| abbr.diagonal wire cutters 斜线切割机n.堤( dyke的名词复数 );坝;堰;沟 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

overflow

|

|

| v.(使)外溢,(使)溢出;溢出,流出,漫出 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

inundate

|

|

| vt.淹没,泛滥,压倒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

dispenses

|

|

| v.分配,分与;分配( dispense的第三人称单数 );施与;配(药) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

attained

|

|

| (通常经过努力)实现( attain的过去式和过去分词 ); 达到; 获得; 达到(某年龄、水平、状况) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

maturity

|

|

| n.成熟;完成;(支票、债券等)到期 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

sickle

|

|

| n.镰刀 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

axis

|

|

| n.轴,轴线,中心线;坐标轴,基准线 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

fixed

|

|

| adj.固定的,不变的,准备好的;(计算机)固定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

intervals

|

|

| n.[军事]间隔( interval的名词复数 );间隔时间;[数学]区间;(戏剧、电影或音乐会的)幕间休息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

pivots

|

|

| n.枢( pivot的名词复数 );最重要的人(或事物);中心;核心v.(似)在枢轴上转动( pivot的第三人称单数 );把…放在枢轴上;以…为核心,围绕(主旨)展开 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

extremity

|

|

| n.末端,尽头;尽力;终极;极度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

perpendicular

|

|

| adj.垂直的,直立的;n.垂直线,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

pestle

|

|

| n.杵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

rotation

|

|

| n.旋转;循环,轮流 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

baker

|

|

| n.面包师 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

bakers

|

|

| n.面包师( baker的名词复数 );面包店;面包店店主;十三 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

pastry

|

|

| n.油酥面团,酥皮糕点 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

strictly

|

|

| adv.严厉地,严格地;严密地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

varied

|

|

| adj.多样的,多变化的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

peripatetic

|

|

| adj.漫游的,逍遥派的,巡回的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

esteemed

|

|

| adj.受人尊敬的v.尊敬( esteem的过去式和过去分词 );敬重;认为;以为 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

concoctions

|

|

| n.编造,捏造,混合物( concoction的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

vendors

|

|

| n.摊贩( vendor的名词复数 );小贩;(房屋等的)卖主;卖方 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

wares

|

|

| n. 货物, 商品 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

skewer

|

|

| n.(烤肉用的)串肉杆;v.用杆串好 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

demolishing

|

|

| v.摧毁( demolish的现在分词 );推翻;拆毁(尤指大建筑物);吃光 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

artistic

|

|

| adj.艺术(家)的,美术(家)的;善于艺术创作的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

dough

|

|

| n.生面团;钱,现款 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

flattened

|

|

| [医](水)平扁的,弄平的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

smeared

|

|

| 弄脏; 玷污; 涂抹; 擦上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

edibles

|

|

| 可以吃的,可食用的( edible的名词复数 ); 食物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

superstitious

|

|

| adj.迷信的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

ply

|

|

| v.(搬运工等)等候顾客,弯曲 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

warding

|

|

| 监护,守护(ward的现在分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

picturesque

|

|

| adj.美丽如画的,(语言)生动的,绘声绘色的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

pestilence

|

|

| n.瘟疫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

apropos

|

|

| adv.恰好地;adj.恰当的;关于 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

beset

|

|

| v.镶嵌;困扰,包围 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

distressingly

|

|

| adv. 令人苦恼地;悲惨地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

bazaars

|

|

| (东方国家的)市场( bazaar的名词复数 ); 义卖; 义卖市场; (出售花哨商品等的)小商品市场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

countenance

|

|

| n.脸色,面容;面部表情;vt.支持,赞同 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

jeers

|

|

| n.操纵帆桁下部(使其上下的)索具;嘲讽( jeer的名词复数 )v.嘲笑( jeer的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

crunching

|

|

| v.嘎吱嘎吱地咬嚼( crunch的现在分词 );嘎吱作响;(快速大量地)处理信息;数字捣弄 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

abjectly

|

|

| 凄惨地; 绝望地; 糟透地; 悲惨地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

beseeching

|

|

| adj.恳求似的v.恳求,乞求(某事物)( beseech的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

primitive

|

|

| adj.原始的;简单的;n.原(始)人,原始事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

yeast

|

|

| n.酵母;酵母片;泡沫;v.发酵;起泡沫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

hips

|

|

| abbr.high impact polystyrene 高冲击强度聚苯乙烯,耐冲性聚苯乙烯n.臀部( hip的名词复数 );[建筑学]屋脊;臀围(尺寸);臀部…的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

gashes

|

|

| n.深长的切口(或伤口)( gash的名词复数 )v.划伤,割破( gash的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

axe

|

|

| n.斧子;v.用斧头砍,削减 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

descends

|

|

| v.下来( descend的第三人称单数 );下去;下降;下斜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

standing

|

|

| n.持续,地位;adj.永久的,不动的,直立的,不流动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

favourable

|

|

| adj.赞成的,称赞的,有利的,良好的,顺利的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

jack

|

|

| n.插座,千斤顶,男人;v.抬起,提醒,扛举;n.(Jake)杰克 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

Christian

|

|

| adj.基督教徒的;n.基督教徒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |