“N asty old cat,” said Griselda, as soon as the door was closed.

She made a face in the direction of the departing visitors and then looked at me and laughed.

“Len, do you really suspect me of having an affair with Lawrence Redding?”

“My dear, of course not.”

“But you thought Miss Marple was hinting at it. And you rose to my defence simply beautifully. Like—like anangry tiger.”

A momentary1 uneasiness assailed2 me. A clergyman of the Church of England ought never to put himself in theposition of being described as an angry tiger.

“I felt the occasion could not pass without a protest,” I said. “But Griselda, I wish you would be a little morecareful in what you say.”

“Do you mean the cannibal story?” she asked. “Or the suggestion that Lawrence was painting me in the nude3! Ifthey only knew that he was painting me in a thick cloak with a very high fur collar—the sort of thing that you could goquite purely4 to see the Pope in—not a bit of sinful flesh showing anywhere! In fact, it’s all marvellously pure.

Lawrence never even attempts to make love to me—I can’t think why.”

“Surely knowing that you’re a married woman—”

“Don’t pretend to come out of the ark, Len. You know very well that an attractive young woman with an elderlyhusband is a kind of gift from heaven to a young man. There must be some other reason—it’s not that I’m unattractive—I’m not.”

“Surely you don’t want him to make love to you?”

“N-n-o,” said Griselda, with more hesitation5 than I thought becoming.

“If he’s in love with Lettice Protheroe—”

“Miss Marple didn’t seem to think he was.”

“Miss Marple may be mistaken.”

“She never is. That kind of old cat is always right.” She paused a minute and then said, with a quick sidelongglance at me: “You do believe me, don’t you? I mean, that there’s nothing between Lawrence and me.”

“My dear Griselda,” I said, surprised. “Of course.”

My wife came across and kissed me.

“I wish you weren’t so terribly easy to deceive, Len. You’d believe me whatever I said.”

“I should hope so. But, my dear, I do beg of you to guard your tongue and be careful of what you say. Thesewomen are singularly deficient6 in humour, remember, and take everything seriously.”

“What they need,” said Griselda, “is a little immorality7 in their lives. Then they wouldn’t be so busy looking for itin other people’s.”

And on this she left the room, and glancing at my watch I hurried out to pay some visits that ought to have beenmade earlier in the day.

The Wednesday evening service was sparsely8 attended as usual, but when I came out through the church, afterdisrobing in the vestry, it was empty save for a woman who stood staring up at one of our windows. We have somerather fine old stained glass, and indeed the church itself is well worth looking at. She turned at my footsteps, and Isaw that it was Mrs. Lestrange.

We both hesitated a moment, and then I said:

“I hope you like our little church.”

“I’ve been admiring the screen,” she said.

Her voice was pleasant, low, yet very distinct, with a clearcut enunciation9. She added:

“I’m so sorry to have missed your wife yesterday.”

We talked a few minutes longer about the church. She was evidently a cultured woman who knew something ofChurch history and architecture. We left the building together and walked down the road, since one way to theVicarage led past her house. As we arrived at the gate, she said pleasantly:

“Come in, won’t you? And tell me what you think of what I have done.”

I accepted the invitation. Little Gates had formerly10 belonged to an Anglo-Indian colonel, and I could not helpfeeling relieved by the disappearance11 of the brass12 tables and Burmese idols13. It was furnished now very simply, but inexquisite taste. There was a sense of harmony and rest about it.

Yet I wondered more and more what had brought such a woman as Mrs. Lestrange to St. Mary Mead14. She was sovery clearly a woman of the world that it seemed a strange taste to bury herself in a country village.

In the clear light of her drawing room I had an opportunity of observing her closely for the first time.

She was a very tall woman. Her hair was gold with a tinge15 of red in it. Her eyebrows16 and eyelashes were dark,whether by art or by nature I could not decide. If she was, as I thought, made up, it was done very artistically17. Therewas something Sphinxlike about her face when it was in repose18 and she had the most curious eyes I have ever seen—they were almost golden in shade.

Her clothes were perfect and she had all the ease of manner of a well-bred woman, and yet there was somethingabout her that was incongruous and baffling. You felt that she was a mystery. The word Griselda had used occurred tome—sinister. Absurd, of course, and yet—was it so absurd? The thought sprang unbidden into my mind: “Thiswoman would stick at nothing.”

Our talk was on most normal lines—pictures, books, old churches. Yet somehow I got very strongly the impressionthat there was something else—something of quite a different nature that Mrs. Lestrange wanted to say to me.

I caught her eye on me once or twice, looking at me with a curious hesitancy, as though she were unable to makeup19 her mind. She kept the talk, I noticed, strictly20 to impersonal21 subjects. She made no mention of a husband orrelations.

But all the time there was that strange urgent appeal in her glance. It seemed to say: “Shall I tell you? I want to.

Can’t you help me?”

Yet in the end it died away—or perhaps it had all been my fancy. I had the feeling that I was being dismissed. Irose and took my leave. As I went out of the room, I glanced back and saw her staring after me with a puzzled,doubtful expression. On an impulse I came back:

“If there is anything I can do—”

She said doubtfully: “It’s very kind of you—”

We were both silent. Then she said:

“I wish I knew. It’s difficult. No, I don’t think anyone can help me. But thank you for offering to do so.”

That seemed final, so I went. But as I did so, I wondered. We are not used to mysteries in St. Mary Mead.

So much is this the case that as I emerged from the gate I was pounced22 upon. Miss Hartnell is very good atpouncing in a heavy and cumbrous way.

“I saw you!” she exclaimed with ponderous23 humour. “And I was so excited. Now you can tell us all about it.”

“About what?”

“The mysterious lady! Is she a widow or has she a husband somewhere?”

“I really couldn’t say. She didn’t tell me.”

“How very peculiar24. One would think she would be certain to mention something casually25. It almost looks, doesn’tit, as though she had a reason for not speaking?”

“I really don’t see that.”

“Ah! But as dear Miss Marple says, you are so unworldly, dear Vicar. Tell me, has she known Dr. Haydock long?”

“She didn’t mention him, so I don’t know.”

“Really? But what did you talk about then?”

“Pictures, music, books,” I said truthfully.

Miss Hartnell, whose only topics of conversation are the purely personal, looked suspicious and unbelieving.

Taking advantage of a momentary hesitation on her part as to how to proceed next, I bade her good night and walkedrapidly away.

I called in at a house farther down the village and returned to the Vicarage by the garden gate, passing, as I did so,the danger point of Miss Marple’s garden. However, I did not see how it was humanly possible for the news of myvisit to Mrs. Lestrange to have yet reached her ears, so I felt reasonably safe.

As I latched26 the gate, it occurred to me that I would just step down to the shed in the garden which youngLawrence Redding was using as a studio, and see for myself how Griselda’s portrait was progressing.

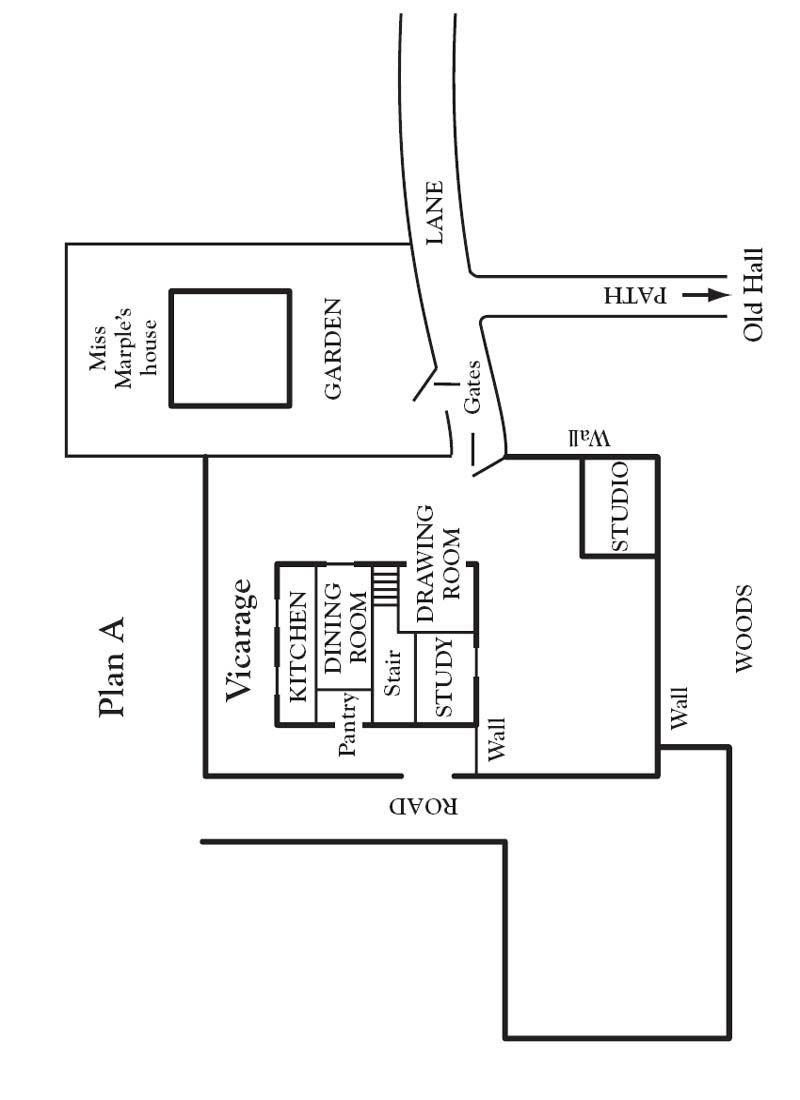

I append a rough sketch27 here which will be useful in the light of after happenings, only sketching28 in such details asare necessary.

I had no idea there was anyone in the studio. There had been no voices from within to warn me, and I suppose thatmy own footsteps made no noise upon the grass.

I opened the door and then stopped awkwardly on the threshold. For there were two people in the studio, and theman’s arms were round the woman and he was kissing her passionately29.

The two people were the artist, Lawrence Redding, and Mrs. Protheroe.

I backed out precipitately30 and beat a retreat to my study. There I sat down in a chair, took out my pipe, and thoughtthings over. The discovery had come as a great shock to me. Especially since my conversation with Lettice thatafternoon, I had felt fairly certain that there was some kind of understanding growing up between her and the youngman. Moreover, I was convinced that she herself thought so. I felt positive that she had no idea of the artist’s feelingsfor her stepmother.

A nasty tangle32. I paid a grudging33 tribute to Miss Marple. She had not been deceived but had evidently suspectedthe true state of things with a fair amount of accuracy. I had entirely34 misread her meaning glance at Griselda.

I had never dreamt of considering Mrs. Protheroe in the matter. There has always been rather a suggestion ofCaesar’s wife about Mrs. Protheroe—a quiet, self-contained woman whom one would not suspect of any great depthsof feeling.

I had got to this point in my meditations35 when a tap on my study window aroused me. I got up and went to it. Mrs.

Protheroe was standing31 outside. I opened the window and she came in, not waiting for an invitation on my part. Shecrossed the room in a breathless sort of way and dropped down on the sofa.

I had the feeling that I had never really seen her before. The quiet self-contained woman that I knew had vanished.

In her place was a quick-breathing, desperate creature. For the first time I realized that Anne Protheroe was beautiful.

She was a brown-haired woman with a pale face and very deep set grey eyes. She was flushed now and her breastheaved. It was as though a statue had suddenly come to life. I blinked my eyes at the transformation36.

“I thought it best to come,” she said. “You—you saw just now?” I bowed my head.

She said very quietly: “We love each other….”

And even in the middle of her evident distress37 and agitation38 she could not keep a little smile from her lips. Thesmile of a woman who sees something very beautiful and wonderful.

I still said nothing, and she added presently:

I still said nothing, and she added presently:“I suppose to you that seems very wrong?”

“Can you expect me to say anything else, Mrs. Protheroe?”

“No—no, I suppose not.”

I went on, trying to make my voice as gentle as possible:

“You are a married woman—”

She interrupted me.

“Oh! I know—I know. Do you think I haven’t gone over all that again and again? I’m not a bad woman really—I’m not. And things aren’t—aren’t—as you might think they are.”

I said gravely: “I’m glad of that.”

She asked rather timorously39:

“Are you going to tell my husband?”

I said rather dryly:

“There seems to be a general idea that a clergyman is incapable40 of behaving like a gentleman. That is not true.”

She threw me a grateful glance.

“I’m so unhappy. Oh! I’m so dreadfully unhappy. I can’t go on. I simply can’t go on. And I don’t know what todo.” Her voice rose with a slightly hysterical41 note in it. “You don’t know what my life is like. I’ve been miserable42 withLucius from the beginning. No woman could be happy with him. I wish he were dead … It’s awful, but I do … I’mdesperate. I tell you, I’m desperate.” She started and looked over at the window.

“What was that? I thought I heard someone? Perhaps it’s Lawrence.”

I went over to the window which I had not closed as I had thought. I stepped out and looked down the garden, butthere was no one in sight. Yet I was almost convinced that I, too, had heard someone. Or perhaps it was her certaintythat had convinced me.

When I reentered the room she was leaning forward, drooping43 her head down. She looked the picture of despair.

She said again:

“I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to do.”

I came and sat down beside her. I said the things I thought it was my duty to say, and tried to say them with thenecessary conviction, uneasily conscious all the time that that same morning I had given voice to the sentiment that aworld without Colonel Protheroe in it would be improved for the better.

Above all, I begged her to do nothing rash. To leave her home and her husband was a very serious step.

I don’t suppose I convinced her. I have lived long enough in the world to know that arguing with anyone in love isnext door to useless, but I do think my words brought to her some measure of comfort.

When she rose to go, she thanked me, and promised to think over what I had said.

Nevertheless, when she had gone, I felt very uneasy. I felt that hitherto I had misjudged Anne Protheroe’scharacter. She impressed me now as a very desperate woman, the kind of woman who would stick at nothing once heremotions were aroused. And she was desperately44, wildly, madly in love with Lawrence Redding, a man several yearsyounger than herself. I didn’t like it.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

momentary

|

|

| adj.片刻的,瞬息的;短暂的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

assailed

|

|

| v.攻击( assail的过去式和过去分词 );困扰;质问;毅然应对 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

nude

|

|

| adj.裸体的;n.裸体者,裸体艺术品 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

purely

|

|

| adv.纯粹地,完全地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

hesitation

|

|

| n.犹豫,踌躇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

deficient

|

|

| adj.不足的,不充份的,有缺陷的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

immorality

|

|

| n. 不道德, 无道义 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

sparsely

|

|

| adv.稀疏地;稀少地;不足地;贫乏地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

enunciation

|

|

| n.清晰的发音;表明,宣言;口齿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

formerly

|

|

| adv.从前,以前 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

disappearance

|

|

| n.消失,消散,失踪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

brass

|

|

| n.黄铜;黄铜器,铜管乐器 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

idols

|

|

| 偶像( idol的名词复数 ); 受崇拜的人或物; 受到热爱和崇拜的人或物; 神像 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

mead

|

|

| n.蜂蜜酒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

tinge

|

|

| vt.(较淡)着色于,染色;使带有…气息;n.淡淡色彩,些微的气息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

eyebrows

|

|

| 眉毛( eyebrow的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

artistically

|

|

| adv.艺术性地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

repose

|

|

| v.(使)休息;n.安息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

makeup

|

|

| n.组织;性格;化装品 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

strictly

|

|

| adv.严厉地,严格地;严密地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

impersonal

|

|

| adj.无个人感情的,与个人无关的,非人称的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

pounced

|

|

| v.突然袭击( pounce的过去式和过去分词 );猛扑;一眼看出;抓住机会(进行抨击) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

ponderous

|

|

| adj.沉重的,笨重的,(文章)冗长的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

casually

|

|

| adv.漠不关心地,无动于衷地,不负责任地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

latched

|

|

| v.理解( latch的过去式和过去分词 );纠缠;用碰锁锁上(门等);附着(在某物上) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

sketch

|

|

| n.草图;梗概;素描;v.素描;概述 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

sketching

|

|

| n.草图 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

passionately

|

|

| ad.热烈地,激烈地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

precipitately

|

|

| adv.猛进地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

standing

|

|

| n.持续,地位;adj.永久的,不动的,直立的,不流动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

tangle

|

|

| n.纠缠;缠结;混乱;v.(使)缠绕;变乱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

grudging

|

|

| adj.勉强的,吝啬的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

entirely

|

|

| ad.全部地,完整地;完全地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

meditations

|

|

| 默想( meditation的名词复数 ); 默念; 沉思; 冥想 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

transformation

|

|

| n.变化;改造;转变 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

distress

|

|

| n.苦恼,痛苦,不舒适;不幸;vt.使悲痛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

agitation

|

|

| n.搅动;搅拌;鼓动,煽动 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

timorously

|

|

| adv.胆怯地,羞怯地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

incapable

|

|

| adj.无能力的,不能做某事的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

hysterical

|

|

| adj.情绪异常激动的,歇斯底里般的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

miserable

|

|

| adj.悲惨的,痛苦的;可怜的,糟糕的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

drooping

|

|

| adj. 下垂的,无力的 动词droop的现在分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

desperately

|

|

| adv.极度渴望地,绝望地,孤注一掷地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |