Caves formed by the Sea and by Volcanic Action.

In this chapter we shall treat of the origin of caves and of their place in physical geography. The most obvious agent in hollowing out caves is the sea. The set of the current, the tremendous force of the breakers, and the grinding of the shingle5, inevitably6 discover the weak places in the cliff, and leave caves as the results of their work, modified in each case by the local conditions of the rock. Caves formed in this manner have certain characters which are easily recognized. Their floors24 are very rarely much out of the horizontal, their outlook is over the sea, and they very seldom penetrate8 far into the cliff. A general parallelism is also to be observed in a group in the same district, and their entrances are all in the same horizontal plane, or in a succession of horizontal and parallel planes. In some cases they are elevated above the present reach of the waves, and mark the line at which the sea formerly9 stood. From their generally inaccessible10 position sea-caves have very rarely been occupied by man, and the history of their formation is so obvious that it requires no further notice. Among them the famous Fingal’s Cave, off the north coast of Ireland, and that of Staffa, on the opposite shore of Scotland, hollowed out of columnar basalt, are perhaps the most remarkable11 in Europe.

In volcanic regions also there are caves formed by the passage of lava12 to the surface of the ground, or by the imprisoned13 steam and gases in the lava while it was in a molten state: but these are of comparatively little importance so far as relates to the general question of caves, from the very small areas which are occupied by active volcanoes in Europe. They have been observed in Vesuvius, Etna, Iceland, and Teneriffe.

Caves in Arenaceous Rocks.

Caves also occur sometimes in sandstones, in which case they are the result of the erosion of the lines of the joints14 by the passage of subaërial water, and if the joints happen to traverse a stratum16 less compacted than the rest, the weak point is discovered, and a hollow is formed extending laterally17 from the original fissure18. The massive25 millstone grit19 of Derbyshire and Yorkshire present many examples of this, as for instance in Kinderscout in the former county. The rocks at Tunbridge Wells also show to what extent the joints in the Wealden sandstones may become open fissures21, more or less connected with caves, on a small scale, by the mere22 mechanical action of water. M. Desnoyers gives instances of the same kind in the Tertiary sandstones of the Paris basin, which have furnished remains23 of rhinoceros24, reindeer25, hyæna, and bear. Caverns, however, in the sandstone are rarely of great extent, and may be passed over as being of small importance in comparison with those in the calcareous rocks.

Caves in Calcareous Rocks of various ages.

It has long been known that wherever the calcareous strata27 are sufficiently28 hard and compact to support a roof, caves are to be found in greater or less abundance. Those of Devonshire occur in the Devonian limestone29; those of Somerset, Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, and Northumberland, as well as of Belgium and Westphalia, in that of the carboniferous age. In France also, those of Maine and Anjou, and most of those of the Pyrenees and in the department of Aude, are hollowed in carboniferous limestone, as well as the greater part of those in North America, in Virginia, and Kentucky. The cave of Kirkdale in Yorkshire, and most of those in Franconia and in Bavaria penetrate Jurassic limestones31, which have received the name of Hohlenkalkstein from the abundance of caverns which they contain. They are developed on a large scale in the Swiss and French Jura, and in some cases afford passage to powerful streams,26 and in others are more or less filled with ice, thus constituting the singular “glacières” that have been so ably explored by the Rev26. G. F. Browne.22

The compact Neocomian and Cretaceous limestones contain most of the caverns of Périgord, Quercy, and Angoumois, and some of those in Provence and Languedoc, those of Northern Italy, Sicily, Greece, Dalmatia, Carniola, and Turkey in Europe, of Asia Minor32 and Palestine.

The tertiary limestones, writes M. Desnoyers,23 offer sometimes, but very rarely, caves that have become celebrated33 for the bones which they contain, such as those of Lunel-Viel, near Montpelier, those of Pondres and Souvignargues, near Sommières (Gard), and of Saint Macaire (Gironde). The same may also be said of the calcaire grossier of the basin of Paris.

Certain rocks composed of gypsum also contain caverns of the same sort as those in the limestones. In Thuringia, for example, near Eisleben, they occur in the saliferous and gypseous strata of the zechstein, and are connected with large gulfs and cirques on the surface, which are sometimes filled with water. In the neighbourhood of Paris, and especially at Montmorency, they contain numerous bones of the extinct mammalia. M. Desnoyers points out their identity, in all essentials, with those in calcareous strata, and infers that they have been produced in the same way. Some of them may have been formed by the removal of the salt, which is very frequently interbedded with the gypsum, by the passage of water. In Cheshire the pumping of the27 brine from the saliferous and gypseous strata produces subterranean34 hollows, which sometimes fall in and eventually cause depressions on the surface, such as those which are now destroying the town of Northwich, and causing the neighbouring tidal estuary35 to extend over what was formerly meadow land. This explanation, however, will not apply to those in the neighbourhood of Paris, because there is no trace of their ever having contained salt.

The Relation of Caves to Pot-holes, “Cirques,” and Ravines.

The caverns hollowed in calcareous rocks present features by which they are distinguished37 from any others. They open, for the most part, on the abrupt38 sides of valleys and ravines at various levels, being arranged round the main axis39 of erosion just as branches are arranged round the trunk of a tree—as, for example, in Cheddar Pass. The transition in some cases from the valley to the ravine, and from the ravine to the cave, is so gradual, that it is impossible to deny that all three are due to the same cause. The caves themselves ramify in the same irregular fashion as the valleys, and are to be viewed merely as the capillaries40 in the general valley system, through which the rainfall passes to join the main channels. Very frequently, however, the drainage has found an outlet41 at a lower level, and its ancient passage is left dry; but in all cases unmistakeable proof of the erosive action of water is to be seen in the sand, gravel42, and clay which compose the floor, as well as in the worn surfaces of the sides and the bottom.

In all districts in which caves occur are funnel43-shaped28 cavities of various sizes, known as “pot-holes” or “swallow-holes” in Britain, as “betoires,” “chaldrons du diable,” “marmites de géants,” in France, and as “kata-vothra” in Greece, in which the rainfall is collected before it finally disappears in the subterranean passages. They are to be seen in all stages; sometimes being mere shallow funnels44, that only contain water after excessive rain, and at others as profound vertical45 shafts46, into which the water is continually falling, as in Helln Pot, in Yorkshire. The cirques, also, described by M. Desnoyers, belong to the same class of cavities, although all those which are mentioned by the Rev. T. G. Bonney,24 at the head of valleys, and in some cases hollowed in shale48 and igneous49 rocks, are most probably to be referred to the vertical, chisel-like action of streams flowing under physical conditions, that resemble those under which the cañons of the Colorado, or of the Zambesi, are being excavated50, and in which frost, ice, and snow have played a very subordinate part.

The intimate relation between pot-holes, caves, ravines, and valleys will be discussed in the rest of this chapter, and illustrated52 by English examples; and then we shall proceed to show that the chemical action of the carbonic acid in the rain-water, and the mechanical friction53 of the sand and gravel, set in motion by the water, by which Professor Phillips explains the origin of caves, will equally explain the pot-holes and ravines by which they are invariably accompanied.

29

The Water-Cave of Wookey Hole, near Wells, Somerset.

Caves may be divided into two classes: those which are now mere passages for water, in which the history of their formation may be studied, and those which are dry, and capable of affording shelter to man and the lower animals. Among the water-caves, that of Wookey Hole25 is to be noticed first, since its very name implies that it was known to the Celtic inhabitants of the south of England, and since it was among the first, if not the first, of those examined with any care in this country, Mr. John Beaumont26 having brought it before the notice of the Royal Society in the year 1680.

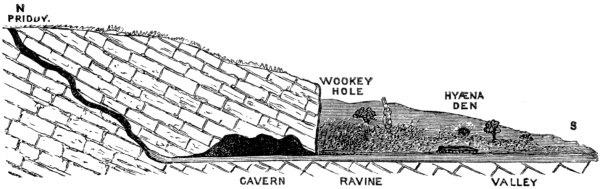

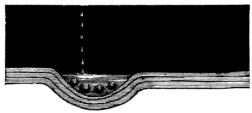

The hamlet of Wookey Hole nestles in a valley, through which flows the river Axe54, and the valley passes insensibly, at its upper end, into a ravine, which is closed abruptly55 by a wall of rock (Fig56. 1), about two hundred feet high, covered with long streamers and festoons of ivy57, and affording scanty58 hold, on its ledges60 and in its fissures, to ferns, brambles, and ash saplings. At its base the river Axe issues, in full current, out of the cave, the lower entrance of which it completely blocks up, since the water has been kept back by a weir61, for the use of a30 paper-mill a little distance away. A narrow path through the wood, on the north side of the ravine, leads to the only entrance now open.27 Thence a narrow passage leads downward into the rock, until, suddenly, you find yourself in a large chamber62, at the water level. Then you pass over a ridge20, covered with a delicate fretwork of dripstone, with each tiny hollow full of water, and ornamented63 with brilliant lime crystals. One shapeless mass of dripstone is known in local tradition as the Witch of Wookey, turned into stone by the prayers of a Glastonbury monk64. Beyond this the chamber expands considerably65, being some seventy or eighty feet high, and adorned66 with beautiful stalactites, far out of the reach of visitors. The water, which bars further entrance, forms a deep pool, which Mr. James Parker managed to cross on a raft (see Appendix I.) into another chamber, which was apparently67 easy of access before the construction of the weir. It was in this further chamber that Dr. Buckland found human remains and pottery68.

Fig. 1.—Diagram of Wookey Hole Cave and Ravine.

The cave has been proved to extend as far as the village of Priddy, about two miles off, on the Mendip hills, by the fact observed by Mr. Beaumont, that the water used in washing the lead ore at that spot, in his time, found its way into the river Axe, and poisoned cattle in31 the valley of Wookey. And this observation has been verified during the last few years by throwing in colour and chopped straw. The stream at Priddy sinks into a swallow-hole (Fig. 1), and has its subterranean course determined69 by the southerly dip of the rock, by which the joints running north and south afford a more free passage to the water than those running east and west. The cave is merely a subterranean extension of the ravine in the same line, as far as the swallow-hole, and all three have been hollowed, as we shall see presently, by the action of the stream and of carbonic acid in the water.

The Goatchurch Cave.

The largest cavern2 in the Mendip hills is that locally known as the Goatchurch, which opens on the eastern side of the lower of the two ravines that branch from the magnificent defile70 of Burrington Combe, about two miles from the village of Wrington, at the height of about 120 feet from the bottom of the ravine. After creeping along a narrow, muddy passage, with a steep descent to the west, at an angle of about 30°, you suddenly pass into a stalactitic chamber of considerable height and size. From it two small vertical shafts lead into the lower set of chambers71 and passages; the first being blocked up, and the second being close to a large barrel-shaped stalagmite, to which Mr. Ayshford Sanford, Mr. James Parker, and myself fastened our ropes when we explored the cave in 1864. The latter affords access into a passage, beautifully arched, and passing horizontally east and west, and just large enough to admit a man walking upright. At the further end numerous open32 fissures, caused by the erosion of the joints in the limestone, cross it at right angles, and pass into several ill-defined chambers, partially73 stalactitic, but for the most part filled with loose, bare, cubical masses of limestone. Two of the transverse fissures lead into a large chamber, at a lower level. At its lower end, on crawling along a narrow passage, we came into a second chamber, also of considerable height and depth, at the bottom of which the noise of flowing water can be heard through two vertical holes, just large enough to admit of access. On sliding down one of these we found ourselves in a third chamber, which was traversed by a subterranean stream, doubtless in part the same which disappears in the ravine, at a point eighty feet above by aneroid measurement. The temperature of the water, as compared with that of the stream outside (49° : 59°), renders it very probable that, between the point of disappearance74 in the ravine and reappearance in the cave, it is joined by a stream of considerable subterranean length, since the water could not have lost ten degrees in the short interval75 which it had to traverse, were it supplied only from the stream in the ravine. From the point of its disappearance in the cave, the water passes downwards76 to join the main current flowing underneath77 Burrington Combe, that gushes78 forth79 in great volume at Rickford. The lowest portion of the cave was eighteen or twenty feet below the stream, and 220 feet below the entrance of the cavern.

On examining the floors of the chambers and passages, we discovered that they were composed of the same kind of sediment80 as that which is now being deposited by the water in Wookey Hole, and there could be no doubt but that they had been originally traversed by water. For33 this to have taken place it is necessary to suppose that, while the Goatchurch was a water cave, the ravine on which it opens was not deeper than the entrance—in other words, that in the interval between the formation and excavation81 of the chambers and passages, to the present time, the ravine has been excavated in the limestone to a depth of a hundred and twenty feet, and the water which originally passed through the entrance has found its way, by a new series of passages, to the point where it appears at the bottom of the cave.

We obtained evidence that the horizontal passage, immediately below the first vertical descent, had been inhabited at a very remote period. At the spot where Mr. Beard, of Banwell, obtained a fine tusk82 of mammoth83, we found a molar of bear, and a fragment of flint, which were imbedded in red earth, and were underneath a crust of stalagmite of about two inches in thickness. It would follow from this, that the date of the formation of this part of the cave was before the time when the traces of elephants, bears, and of man were introduced.

The cave is the resort of numerous badgers84. On hiding ourselves in one of the transverse fissures, and throwing our light across the horizontal passage, these animals ran to and fro across the lighted field with extraordinary swiftness, and had it not been for the white streaks85 on the sides of their heads, which flashed back the light, they would not have been observed. Though they are rarely caught, they must be abundant in the district.

Like all the other large caverns in the district, it has its legends. The dwellers86 in the neighbourhood, who have never cared to explore its recesses88, relate that a certain34 dog put in here found its way out, after many days, at Wookey Hole, having lost all its hair in scrambling89 through the narrow passages. At Cheddar the same legend is appropriated to the Cheddar cave. At Wookey the dog is said to have travelled back to Cheddar. Some eighteen years ago, while exploring the limestone caves at Llanamynech, on the English border of Montgomeryshire, I met with a similar story. A man playing the bagpipes90 is said to have entered one of the caves, well provisioned with Welsh mutton, and after he had been in for some time his bagpipes were heard two miles from the entrance, underneath the small town of Llanamynech. He never returned to tell his tale. The few bones found in the cave are supposed to be those which he had picked on the way. This is doubtless another form of the story of the dog; both owe their origin to the vague impression, which most people have, of the great extent of caverns, and both versions are equally current in France and Germany.

The Water-caves of Derbyshire.

The celebrated cavern of the Peak, at Castleton in Derbyshire, presents the same essential character as that of Wookey Hole. It runs into the hill-side at the end of the ravine, and is traversed by a powerful stream of water, which has been met with in driving an horizontal adit in lead-mining at a considerable distance from the entrance, and finally traced to a distant swallow-hole. At a little distance from Buxton a smaller cave, known as Poole’s Cavern, is in part traversed by water, which has found an outlet at a lower level, and allowed of the present entrance being used by the Brit-Welsh35 (Romano-Celtic) inhabitants of the district as a habitation in the fifth and sixth centuries.28 There are, besides these, very many others, some known, others unknown, that debouch91 on the sides of the dales in Derbyshire and Staffordshire, and are all well worthy92 of examination, since they illustrate51 not merely the history of the formation of caves, but also have been proved to contain works of art, pottery and flint implements93, and the remains of animals, such as the mammoth and rhinoceros.

The Water-caves of Yorkshire.

The caves in the mountain limestone of Yorkshire rival in size those of Carniola, or those of Greece, and they are to be seen in all stages of formation. In their gloomy recesses all the higher qualities of a mountaineer may be exercised, and there is sufficient danger to give a keen zest94 to their exploration. The mountain streams sometimes plunge95 into a yawning chasm96, locally known as a pot, and at others emerge from the dark portals of a cave in full current. There is, perhaps, no place in the world where the subterranean circulation of water may be studied with better advantage.

Ingleborough forms a centre from which the rainfall on every side finds its way into the dales, through a system of caves more or less complicated, which during the last forty years have been thoroughly97 explored by Mr. Farrer, Mr. Birkbeck, and Mr. Metcalfe. On the south it collects in a ravine, and then leaps into a deep bottle-shaped hole called “Gaping98 Gill,” into which Mr.36 Birkbeck unsuccessfully attempted to descend99, the sharp edges of the rock cutting the rope, and very nearly causing a serious accident. In depth it is about three hundred feet. The stream thence finds its way through a series of chambers and passages until it reappears in the famous Ingleborough cave, that was explored by Mr. Farrer in the year 1837, and proved to pass into the rock between seven and eight hundred yards.

The present entrance of the Ingleborough cave29 is dry, except after heavy rains, when the current reverts100 to its old passage. The following admirable account of the interior is given by Professor Phillips:—30

“From Mr. Farrer’s plan and description, as given in the ‘Proceedings of the Geological Society,’ June 14, 1848, and from information obligingly communicated to me, a clear notion of the history of this most instructive spar grotto101 may be formed. For about eighty yards from the entrance the cave has been known immemorially. At this point Josiah Harrison, a gardener in Mr. Farrer’s service, broke through a stalagmitical barrier which the water had formed, and obtained access to a series of expanded cavities and contracted passages, stretching first to the N., then to the N.W.; afterwards to the N. and N.E., and finally to the E., till after two years spent in the interesting toil102 of discovery, at a distance of 702 yards from the mouth, the explorers rested from their labours in a large and lofty irregular grotto, in which they heard the sound of water falling in a still more advanced subterranean recess87. It has been ascertained103, at no inconsiderable personal risk, that37 this water falls into a deep pool or linn at a lower level, beyond which further progress appears to be impracticable. In fact Mr. Farrer explored this dark lake by swimming—a candle in his cap and a rope round his body.

“In this long and winding104 gallery, fashioned by nature in the marble heart of the mountain, floor, roof, and sides are everywhere intersected by fissures which were formed in the consolidation105 of the stone. To these fissures and the water which has passed down them, we owe the formation of the cave and its rich furniture of stalactites. The direction of the most marked fissures is almost invariably N.W. and S.E., and when certain of these (which in my geological work I have called master fissures) occur, the roof of the cave is usually more elevated, the sides spread out right and left, and often ribs106 and pendants of brilliant stalactite, placed at regular distances, convert the rude fissure into a beautiful aisle107 of primæval architecture. Below most of the smaller fissures hang multitudes of delicate translucent108 tubules, each giving passage to drops of water. Splitting the rock above, these fissures admit, or formerly admitted, dropping water: continued through the floor, the larger rifts109 permit, or formerly permitted, water to enter or flow out of the cave. By this passage of water, continued for ages on ages, the original fissure was in the first instance enlarged, through the corrosive110 action of streams of acidulated water; by the withdrawal111 of the streams to other fissures, a different process was called into operation. The fissure was bathed by drops instead of streams of water, and these drops, exposed to air currents and evaporation112, yielded up the free carbonic acid to the air and the salt of lime to the rock. Every38 line of drip became the axis of a stalactitical pipe from the roof; every surface bathed by thin films of liquid became a sheet of sparry deposit. The floor grew up under the droppings into fantastic heaps of stalagmite, which, sometimes reaching the pipes, united roof and floor by pillars of exquisite113 beauty.”

At the time of its exploration, the water stood at a considerably higher level inside than at the present time, and formed deep pools. The barrier of dripstone has been cut through, and the water level lowered, and a passage made for a considerable distance. Inside, the old water line, which separated the subaërial from the subaqueous dripstone, is very distinct, the former being deposited in thick bosses, crumpled114 curtains, drops, straws, pyramids, and other fantastic drip-structures, while the latter is honeycombed, and composed of rounded, grape-like masses. Between them an ice-like coating of stalagmite forms a dividing line, now supported in mid115 air, but that formerly shot across the surface of the pools that have been drained, or rested on the mud and stones which had been brought down by the stream in ancient times. In some places it still rests on the surface of the pools.

A stalactitic curtain on the right-hand side presents a very singular appearance, its surface being covered with an abundant crop of tiny club-like bodies about one-tenth of an inch in length, and consisting each of a shining drop of water, enclosing a minute fungus116. These may possibly explain in some degree the peculiar117 fungoid-appearance of certain small bosses of dripstone which I have met with in the caves of Pembrokeshire: for an accumulation of carbonate of lime on such a nucleus118 would produce the forms which they assume (see Fig. 17).

39 There are also magnificent groups of dripstone, and each joint15 in the rock is adorned with lines, and pipes, and fringes of calc spar, or widened out into roof-shaped hollows, and traversed by deep, vertical grooves119, caused by the passage of water laden120 with carbonic acid. The general surface of the roof, where the rock is bare, has had its fossils etched out by the acidulated water. In one place you may stand under a branching coral, with its sides and base distinctly marked, and in another fossil shells stand out almost in their original beauty.

Rate of the Accumulation of Stalagmite.

The rate at which the calcareous matter is being deposited at the present time is very easy to be estimated, for that accumulated since the passage was cleared out is white, and contrasts with the dirty, grey-red colour of the older kind. In one case a thickness of 0·24 had been formed in thirty-five years, by the water flowing down the side of the passage excavated by Mr. Farrer, while in another, in about the same time, 0·05 inch had been formed. This would give an annual accumulation of 0·0068 in the one case, and in the other about one-fifth of that amount. This rate does not agree with the rate of increase noted121 by Mr. Farrer and Professor Phillips in the case of a large stalagmite called the Jockey Cap, on which a line of drops is continually falling from one point in the roof. Its circumference122 in 1839 measured 118 inches, in 1845, 120 inches, and in 1873, I found it to be 128 inches. The annual rate of increase from 1845 to 1873 is ·2941 inch, and that from 1839 to 1845 is ·2857. I found, however, that the most remarkable increase was that40 in height. In 1845 its apex123 was 95·25 inches from the roof, in 1873, 87 inches, which would imply an annual deposit of not less than ·2946. (See Appendix II.) At this rate it will arrive at the roof in about 295 years. But even this comparatively short lapse124 of time will probably be diminished by the growth of a pendant stalactite above, that is now being formed in place of that which measured 10 inches in 1845, and has since been accidentally destroyed.

It is very possible that the Jockey Cap may be the result, not of the continuous, but of the intermittent125 drip of water containing carbonate of lime, and that therefore the present rate of growth is not a measure of its past or future condition. Its age in 1845 was estimated by Professor Phillips at 259 years, on the supposition that all or nearly all of the carbonate of lime in each pint126 was deposited. If, however, it grew at its present rate, it may be not more than 100 years old; and if it be taken as a measure of the rate generally, all the stalagmites and stalactites in the cave may not date further back than the time of Edward III.

It is evident, from this instance of rapid accumulation, that the value of a layer of stalagmite in measuring the antiquity127 of deposits below it, is comparatively little. The layers, for instance, in Kent’s Hole, which are generally believed to have demanded a considerable lapse of time, may possibly have been formed at the rate of a quarter of an inch per annum, and the human bones which lie buried under the stalagmite in the cave of Bruniquel, are not for that reason to be taken to be of vast antiquity. It may be fairly concluded, that the thickness of layers of stalagmite cannot be used as an argument in support of the remote age of the strata41 below. At the rate of a quarter of an inch per annum, twenty feet of stalagmite might be formed in 1,000 years.

The Descent into Helln Pot.

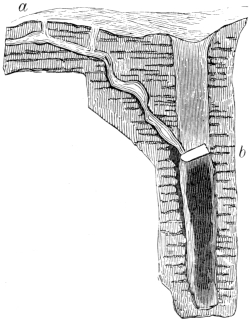

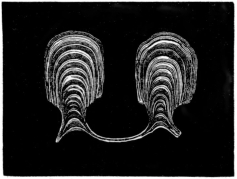

The subterranean passages grouped round Helln Pot, a tremendous chasm near Selside, on the east of Simon’s Fell in Ribblesdale, illustrate in a remarkable degree the mode in which the water is at present wearing away the rock. Those which have been explored constitute the Long Churn Cavern, which is comparatively easy of access through a hole known as Diccan Pot (Fig. 2, a). On descending128 into it, the visitor finds himself in the bed of a stream that now roars in a waterfall, now gurgles over the large fallen blocks from the roof, and that here and there has worn for itself deep pools by the mechanical friction of the sand and pebbles129 brought down by the current. If it be followed down after passing over a waterfall, the light of day is seen streaming upwards130 beneath the feet from the point where the water leaps into the great chasm of Helln Pot (Figs131. 2, b. 3, a). Above the entrance there is a complicated network of passages, some dry, and some containing streams which have not yet been fully72 explored.

Fig. 2.—Diagram of Helln Pot and the Long Churn Cavern.

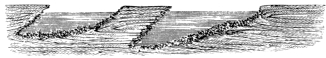

42 The two actions by which caves are hewn out of the calcareous rock are seen here in operation side by side. Below the level of the stream the rock is seen to be smoothed and polished by the mechanical action of the materials swept down by the current. Above the water-level the sides of the cave are honeycombed and eaten into the most fantastic and complex shapes, the resultant surface (see Fig. 7) bearing small points and keen knife-edges of stone, that stand out in relief and mark the less soluble132 portions of the rock. This is due to the chemical effect of the carbonic acid in the water percolating133 through the strata.

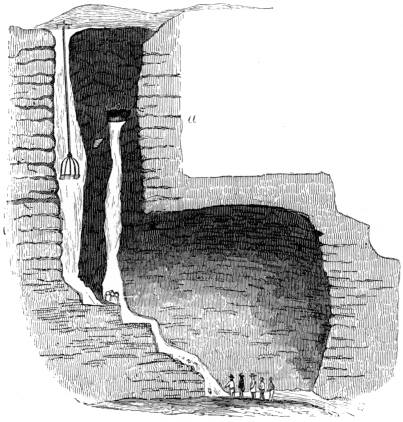

Fig. 3.—Diagram of Helln Pot.

The Helln Pot, into which the stream flowing through the Long Churn Cave falls, is a fissure (Figs. 2, 3, 4)43 a hundred feet long by thirty feet wide, that engulfs134 the waters of a little stream on the surface, which are dissipated in spray long before they reach the bottom. From the top you look down on a series of ledges, green with ferns and mosses135, and, about a hundred feet from the surface, an enormous fragment of rock forms a natural bridge across the chasm from one ledge59 to another. A little above this is the debouchement of the stream flowing through the Long Churn Cave (Fig. 3, a), through which Mr. Birkbeck and Mr. Metcalfe made the first perilous137 descent in 1847. The party, consisting of ten persons, ventured into this awful chasm with no other apparatus138 than ropes, planks139, a turn-tree, and a fire-escape belt. On emerging from the Long Churn Cave they stood on a ledge of rock about twelve feet wide, and which gave them free access to the “bridge” (Fig. 2, b). This was a rock ten feet long, which rested obliquely140 on the ledges. Having crossed over this, they crept behind the waterfall which descended141 from the top, and fixed142 their pulley, five being let down while the rest of the party remained behind to hoist143 them up again. In this way they reached the bottom of the pot, which before had never been trod by the foot of man. Thence they followed the stream downwards as far as the first great waterfall, down which Mr. Metcalfe was venturesome enough to let himself with a rope, and to push onwards until daylight failed. He was within a very little of arriving at the end of the cave into which the stream flows, but was obliged to turn back to the daylight without having accomplished144 his purpose. The whole party eventually, after considerable danger and trouble, returned safely from this most bold adventure.

A second descent was made in 1848 from the surface,44 and a third in the spring of 1870, in both of which Mr. Birkbeck took the lead. The apparatus employed consisted of a windlass (Fig. 3), supported on two baulks of timber, and a bucket, covered with a shield, sufficiently large to hold two people, and two guiding ropes to prevent the revolution of the bucket in mid air. There was also a party of navvies to look after the mechanical contrivances, and two ladders about eight feet long to provide for contingencies145 at the bottom. Thirteen of us went down, including three ladies. As we descended, the fissure gradually narrowed, until at the bottom it was not more than ten feet wide. The actual vertical descent was a hundred and ninety-eight feet. After running the gauntlet of the waterfall we landed in the bed of the stream, which hurried downwards over large boulders147 of limestone and lost itself in the darkness of a large cave, about seventy feet high. We traced it downwards, through pools and rapids to the first waterfall, of about twenty feet. This obstacle prevented most of the party going further, for the ladders were too short to reach to the bottom. By lashing148 them together, however, and letting them down, we were able to reach the first round with the aid of a rope, and to cross over the deep pool at the bottom. Thence we went on downwards through smaller waterfalls and rapids, until we arrived at a descent into a chamber, where the roar of water was deafening149. Down to this point the daylight glimmered150 feebly, but here our torches made but little impression on the darkness. One of the party volunteered to go down with a rope, and was suddenly immersed in a deep pool; the rest, profiting by his misadventure, managed to cling on to small points of rock, and eventually to reach the floor45 of the chamber. We stood at last on the lowest accessible point of the cave, about 300 feet from the surface. It was indeed one of the most remarkable sights that could possibly be imagined. Besides the waterfall down which we came, a powerful stream poured out of a cave too high up for the torches to penetrate the darkness, and fell into a deep pool in the middle of the floor, causing such a powerful current of air that all our torches were blown out except one. The two streams eventually united and disappeared in a small black circling pool, which completely barred further ingress.

Fig. 4.—Diagram of Helln Pot, showing Waterfall at the Bottom.

The floor of the pot and the cave was strewn with masses of limestone rounded by the action of the streams; and the water-channels were smoothed and46 grooved151 and polished, in a most extraordinary way, by the silt152 and stones carried along by the current. Some of the layers of limestone were jet black, and others were of a light fawn-colour, and as the strata were nearly horizontal, the alternation of colours gave a peculiarly striking effect to the walls. Beneath each waterfall was a pool more or less deep, and here and there in the bed of the stream were holes, drilled in the rock by stones whirled round by the force of the water. High up, out of the present reach of the water, were old channels, which had evidently been watercourses before the pot and cave had been cut down to their present level. In the sides of the pot there are two vertical grooves reaching very nearly from the top to the bottom, which are unmistakeably the work of ancient waterfalls. There was no stalactite, but everywhere the water was wearing away the rock and enlarging the cave. We found our way back without any difficulty, a small passage on the right-hand side enabling us to avoid the very unpleasant task of scrambling up two of the waterfalls. We arrived finally at the top, after about five hours’ work in the cave, wet to the skin.

We had very little trouble in making this descent, because of the completeness of Mr. Birkbeck’s preparations; but we could fully realize what a dangerous feat36 the first explorers performed when they ventured into an unknown chasm, comparatively unprepared. The very name “Helln Pot,” = Ællan Pot, or Mouth of Hell, testifies to the awe153 with which the Angles looked down into its recesses.31

Such is the interior of one of those great natural laboratories in which water is wearing away the solid47 rock, either hollowing it into caves or cutting it into ravines. At the bottom of Helln Pot it was impossible not to realize, that the enormous chasm had been formed by the same action as that by which it was being deepened before our eyes. It was merely a portion of the vast cave into which it led, which had been deprived of its roof, and opened out to the light of heaven. The bridge was but a fragment of the roof which happened to fall upon the two ledges. The rounded masses of rock at the bottom are fragments that have fallen probably within comparatively modern times. The absence of stalactites and of stalagmites proves that the destructive action is rapidly going on.

The water-course at the bottom contained pebbles and boulders of limestone, and gritstone rounded by friction against one another and the rocky floor. The gritstone has probably been derived154 from the wreck155 of the boulder146 clay on the surface above the Helln Pot, and ultimately torn from the millstone grit of the higher hills in the district.

Caves and Pots at Weathercote.

Fig. 5.—Waterfall in Pot-hole at Weathercote.

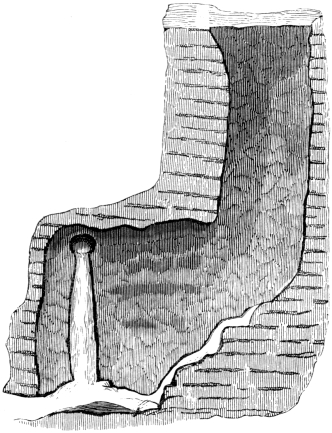

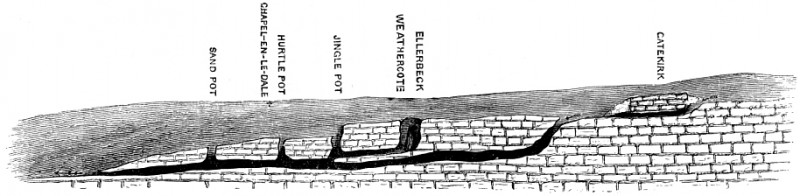

On the north side of Ingleborough the series of caves and pots round the little Church of Chapel-en-le-Dale are especially worthy of attention. The chasm at Weathercote opens suddenly in the hill-side, and is perfectly156 accessible to visitors. You come suddenly upon a cleft157 a hundred feet deep, with its ledges covered with mosses, ferns, and brambles; at one end a body of water rushes from a cave, and under a great bridge of rock, and falls seventy-five feet, a mass of snow-white foam158 filling the bottom with spray (Fig. 5). The large masses of rock piled in wild confusion at the48 bottom, the dark shadows of the overhanging ledges, and the thick covering of green moss136, to which the spray clings in tiny glittering drops, form a picture which cannot easily be forgotten. In the sunshine an almost circular rainbow is to be seen from the bottom. The stream passes from the bottom into a cave, and thence downwards to two large pots (Fig. 6), about two hundred yards away. In flood-time the channel has been known to become blocked up, and Weathercote has been filled to the brim. Usually after heavy rains the current is said to flow so violently into the first of the pot-holes, that it throws up stones at least thirty or forty feet from the bottom, with a peculiar rattling159 noise. From this strange phenomenon it is known as Jingle160 Pot, while the lower of the two is termed Hurtle Pot, because in49 flood-time the water whirls so fast round, that it is “hurtled” out at the top. The water flowing through Weathercote is derived from the little stream of Ellerbeck, which disappears in the limestone hills about a mile to the north, and runs at right angles to Dalebeck, or the stream flowing down to Ingleton, which it has been proved to join at a spot below Jingle Pot, by Mr. Metcalfe, who made his way down into it from the chasm of Weathercote.

Fig. 6.—Diagram of Subterranean Course of Dalebeck.

The course of Dalebeck, as you pass up the valley of Chapel-en-le-Dale, affords a striking instance of the dependence161 of scenery upon the nature of the rock. In its lower portion it has cut out for itself a deep ravine in the hard Silurian strata, in which you come upon the waterfalls, deep pools, and trees, that look as if they had been transported bodily from the district of Cader Idris, and inserted into the limestone scenery of the dales. The Silurian rocks are very much contorted, and on their waterworn edges lie the nearly horizontal limestone strata, in which the upper part of the valley has been scooped162. As we rise the ravine opens into a valley (Fig. 6), along which the50 beck flows, until suddenly it is lost in a fissure, at a place called Godsbridge. Its subterranean course is marked, first of all, by a small depression known as Sandpot, and still higher by Hurtle Pot. It ultimately reappears at the surface, above Weathercote, and after passing through a picturesque163 cavern, known as the Gatekirk, its fountainhead is reached. The subterranean portions of its course are in the same right line as the open valley, and the pot-holes have been formed in the same manner as Helln Pot, by the passage of water at a time when the drainage found its way down the valley at a higher level than at present, very much as it does now in times of extraordinary floods.

Water-caves such as these are by no means uncommon164 in Yorkshire. In the dales there is scarcely a mass of limestone without its subterranean water system, as well as channels deserted165 by water, which are now dry caves situated166 at higher levels. These are always arranged on the line of the natural drainage, and generally open on the sides of the valleys and precipices167. If you look northward169 from the flat crown of Ingleborough, you can see the ravines which radiate from it on the surface of the shale below, abruptly ending in pot-holes when they reach the limestone. In each case the streams reappear, issuing out of the caves at the points in Chapel-en-le-Dale, where the horizontal beds of limestone rest on the upturned edges of the impermeable170 Silurian rocks.

The Formation of Caves and their Relation to Pot-holes and Ravines.

The general conditions under which caves occur in limestone rocks, and the phenomena171 which they present,51 may be gathered from the above examples. Universally the pot-holes, ravines, and caverns are so associated together, that there can be but little doubt that they are due to the operation of the same causes.

It requires but a cursory172 glance to see at once that running water was the main agent. The limestone is so traversed by joints and lines of shrinkage, that the water rapidly sinks down into its mass, and collects in small streams, which owe their direction to the dip of the strata and the position of the fissures. These channels are being continually deepened and widened by the mere mechanical action of the passage of stones and silt. But this is not the only way in which the rock is gradually eroded173. The limestone is composed in great part of pure carbonate of lime, which is insoluble in water. It is, however, readily dissolved in any liquid containing carbonic acid, which is an essential part of our atmosphere, is invariably present in the rain-water, and is given off by all organic bodies. By this invisible agent the hard crystalline rock is always being attacked in some form or another. The very snails174 that take refuge in its crannies leave an enduring mark of their presence in a surface fretted175 with their acid exhalations, which sometimes pass current among geologists176 for the borings of pholades, and are the innocent cause of much speculation177 as to the depression of the mountain-tops beneath the sea in comparatively modern times. The carbonic acid taken up by the rain is derived, in the main, from the decomposing178 vegetable matter which generally forms the surface soil on the limestone.

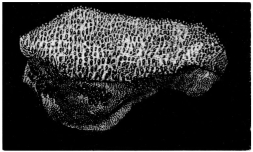

Fig. 7.—Diagram of an acid-worn joint, Doveholes, Derbyshire.

The view from the ancient camp on the top of Ingleborough offers a striking example of the effect of rain-water in eroding179 the surface of the limestone. As you52 look down over the dark crags of millstone grit, great, grey, pavement-like masses of limestone strike the eye, standing180 above the heather, perfectly bare, and in the distance resembling clearings, and in rainy weather sheets of snow. On approaching them the surface of erosion becomes more and more apparent, and the shapes due to the mere accident of varying hardness in the rock, or the varying quantity of water passing over it, present a most astonishing variety. There are, however, general principles underlying181 the confusion. The lines of joints in the strata being lines of weakness, searched out by the acid-laden water, have been widened into chasms182, sometimes of considerable depth; and as they cross at right angles, the whole surface is formed of rectangular masses, each insulated from its fellow, and some of them detached from the strata beneath so as to form rocking-stones. The mode in which the acid has attacked one of these joints in the limestone of Doveholes in Derbyshire is represented in Figure 7, the surface being honeycombed and worn into sharp points, solely183 by chemical action. The minute fossil-shells also, and fragments of crinoid standing out in bold relief, lead to the same conclusion—that the denuding184 agent is chemical and not mechanical. Each of the upper surfaces of the blocks is traversed by small depressions, which are valley systems in miniature, in which the tiny valleys converge185 into a main trunk leading into the nearest chasm. There are also tiny caves and hollows, that are sometimes mistaken for borings made by pholas. In the chasms the vegetation is most luxuriant, and the dark green fronds186 of harts-tongue, the delicate53 Lady-fern, and the graceful187 Asplenium nigrum, grow with a rare luxuriance.

In these pavements every feature of limestone scenery is represented on a minute scale. There are the valley systems on the surface, determined by the direction of the drainage; the long chasms represent the open valleys and ravines, and the caves and hollows, for the most part, run in the line of the joints.

The carbonic acid has left precisely188 the same kind of proof of its work within the caves as we find above-ground; and it would necessarily follow, that to it, as well as to the mechanical power of the waters flowing through them, their formation and enlargement must be due, as Professor Phillips has pointed189 out in his “Rivers, Mountains, and Sea Coast of Yorkshire,” pp. 30–1.

From the preceding pages it will be seen that caves in calcareous rocks are merely passages hollowed out by water, which has sought out the lines of weakness, or the joints formed by the shrinkage of the strata during their consolidation. The work of the carbonic acid is proved, not merely by the acid-worn surfaces of the interior of the caves, but also by the large quantity of carbonate of lime which is carried away by the water in solution. That, on the other hand, of the mechanical friction of the stones and sand against the sides and bottom of the water-courses, is sufficiently demonstrated by their grooved, scratched, and polished surfaces, and by the sand, silt, and gravel carried along by the currents. The generally received hypothesis, that they have been the result of a subterranean convulsion, is disproved by the floor and roof being formed, in very nearly every case, of solid rock; for it would be unreasonable54 to hold that any subterranean force could act from below, in such a manner as to hollow out the complicated and branching passages, at different levels, without affecting the whole mass of the rock. Nor is there cause for holding the view put forth by M. Desnoyers32 or M. Dupont,33 that they are the result of the passage of hydrothermal waters. The causes at present at work, operating through long periods of time, offer a reasonable explanation of their existence in every limestone district; and those which are no longer watercourses can generally be proved to have been formerly traversed by running water, by the silt, sand, and rounded pebbles which they contain. In their case, either the drainage of the district has been changed by the upheaval190 or depression of the rock, or the streams have searched out for themselves a passage at a lower level.

But if caves have been thus excavated, it is obvious that ravines and valleys in limestone districts are due to the operation of the same causes. If, for instance, we refer to Figures 1 and 6, we shall see that the open valley passes insensibly into a ravine, and that into a cave. The ravine is merely a cave which has lost its roof, and the valley is merely the result of the weathering of the sides of the ravine. There can be no manner of doubt but that, in both these cases, the ravine is gradually encroaching on the cave, and the valley on the ravine; and if the strata be exposed to atmospheric agencies long enough, the valley of the Axe will extend as far as Priddy (Fig. 1), and that of Dalebeck to the watershed191 above the Gatekirk cave (Fig. 6).

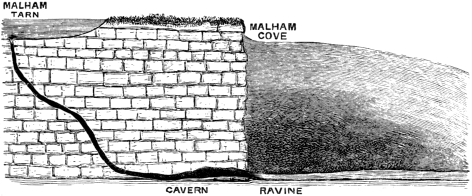

55 In the same manner the lofty precipice168 of Malham Cove7, near Settle, in Yorkshire (Fig. 8), is slowly falling away and uncovering the subterranean course of the Aire. Eventually the ravine thus formed will extend as far as Malham Tarn192, and the Aire flow exposed to the light of day from its source to the sea.34

Fig. 8.—Diagram of Source of the Aire at Malham.

This view is applicable to many if not to all ravines and valleys in calcareous rocks, such as the Pass at Cheddar, or the gorge193 of the Avon at Clifton, and those of Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and Wales. And since the agents by which the work is done are universal, and calcareous rock for the most part of the same chemical composition, the results are the same, and the calcareous scenery everywhere of the same type. In the lapse of past time, so enormous as to be incapable194 of being grasped by the human intellect, these agents are fully capable of producing the deepest ravines, the widest valleys, and the largest caves.

This view of the relation of caves to ravines was so strongly held by M. Desnoyers, that he terms the latter “cavernes à ciel ouvert.” I arrived independently at56 the same conclusion after the study of the scenery of limestone for many years.

In many cases, however, in northern latitudes195 and in high altitudes, the ravine or valley so formed has been subsequently widened and deepened by glacial action. That, for instance, of Chapel-en-le-Dale bears unmistakeable evidence of the former flow of a glacier196, in the roches moutonnées and travelled blocks that it contains. To this is due the flowing contour and even slope of its lower portion.

The pot-holes and “cirques” in calcareous rocks with no outlet at the surface, may also be accounted for by the operation of the same causes as those which have produced caves. Each represents the weak point towards which the rainfall has converged197, caused very generally by the intersection198 of the joints. This has gradually been widened out, because the upper portions of the rock would be the first to seize the atoms of carbonic acid, and thus be dissolved more quickly than the lower portions. Hence the funnel shape which they generally assume, and which can be studied equally in the compact limestone or in the soft upper chalk. They are to be seen on a small scale also in all limestone “pavements.” Sometimes, however, the first chance which the upper portions of the funnels have of being eroded by the acidulated water, is more than counter-balanced by the increased quantity converging199 at the bottom, and the funnel ends in a vertical shaft47. If the area in the rock thus excavated be sufficiently large to allow of the development of a current of water, the mechanical action of the fragments swept along its course will have an important share in the work, as we have seen to be the case in Helln Pot.

Caves not generally found in Line of Faults.

In some few cases the lines of weakness which have been worn into caves, pot-holes, ravines, and valleys, may have been produced, as M. Desnoyers believes, by subterranean movements of elevation200 and depression; but in all those which I have investigated the faults do not determine the direction of the caverns. The mountain limestone of Castleton, in Derbyshire, offers an example of caves intersecting faults without any definite relation being traceable between them. The ramifications201 of the Peak cavern traverse the Speedwell Mine nearly at right angles, and the water flowing through it has been traced, Mr. Pennington informs me, to a swallow-hole near Chapel-en-le-Frith, running across two, if not three faults, which are laid down in the geological map. As a general rule caverns are as little affected202 by disturbance203 of the rock as ravines and valleys which have been formed in the main irrespective of the lines of fault.

M. Desnoyers points out the close analogy between caverns and mineral veins204, and infers that both are due to the same causes. This, undoubtedly205, exists in that class of veins which are known to miners as “pipe” and “flat veins;” and there is clear proof, in the majority of cases, that the cavities in which the minerals occur have been formed by the action of running water, and have subsequently been more or less filled with their mineral contents; and these have been deposited on the sides of the cavity by the same “incretionary35”58 action, as that by which dripstone is now being formed in the present caves from the solution of carbonate of lime. Such veins present every conceivable form of irregularity, and frequently contain silt, sand, and gravel, which have been left behind by their streams, and their history is identical with that of the caverns.

It is not so, however, with the second class of veins, the “rake,” “right running,” and “cross courses,” as the miners term them, or those which occupy lines of fault. The fissures which contain the ore are proved very frequently, by their scratched and grooved sides, and polished surfaces or slicken-sides, to have been the result of subterranean movements by which the rock has been broken by mechanical force. They have been subsequently modified, in various ways, by the passage of water, and filled with minerals, in the same manner as the preceding class. With this exception they present no analogy to the caverns, with which they contrast strongly in their rectilinear direction, as well as in their purely206 mechanical origin.

The various Ages of Caves.

It is very probable that caves were formed in calcareous rocks from the time that they were raised to the level of the sea, since they abound207 in the Coral Islands. “Caverns,” writes Prof. Dana,36 “are still more remarkable on the Island of Atiu, on which the coral-reef59 stands at about the same height above the sea as on Oahu. The Rev. John Williams states—that there are seven or eight of large extent on the Island of Tuto; one he entered by a descent of twenty feet, and wandered a mile in one only of its branches, without finding an end to ‘its interminable windings208.’ He says—‘Innumerable openings presented themselves on all sides as we passed along, many of which appeared to be equal in height, beauty, and extent to the one we were following. The roof, a stratum of coral-rock fifteen feet thick, was supported by massy and superb stalactitic columns, besides being thickly hung with stalactites from an inch to many feet in length. Some of these pendants were just ready to unite themselves to the floor, or to a stalagmitic column rising from it. Many chambers were passed through whose fret-work ceilings and columns of stalactites sparkled brilliantly, amid the darkness, with the reflected light of our torches. The effect was produced not so much by single objects, or groups of them, as by the amplitude209, the depth, and the complications of this subterranean world.’”

Calcareous rocks might, therefore, be expected to contain fissures and caves of various ages. In the Mendip Hills they have been proved by Mr. Charles Moore to contain fossils of Rhætic age, the characteristic dog-fishes, Acrodus minimus, and Hybodus reticulatus, the elegant sculptured Ganoid fish, Gryrolepis tenuistriatus, and the tiny marsupials, Microlestes and its allies. This singular association of terrestrial with marine210 creatures is due to the fact, that while that area was being slowly depressed211 beneath the Rhætic and Liassic seas, the remains were mingled212 together on the coast-line, and washed into the crevices213 and holes in the rock.

60 The older caves and fissures have very generally been blocked up by accumulations of calc-spar or other minerals, and they are arranged on a plan altogether independent of the existing systems of drainage.

It is a singular fact that no fissures or caves should, with the above exception, contain the remains of animals of a date before the Pleistocene age. There can be but little doubt that they were used as places of shelter in all ages, and they must have entombed the remains of the animals that fell into them, or were swept into them by the streams. Caves there must have been long before, and the Eocene Palæotheres, and Anoplotheres met their death in the open pit-falls, just as the sheep and cattle do at the present time. The Hyænodon of the Meiocene had, probably, the same cave-haunting tastes as his descendant, the living Hyæna, and the marsupials of the Mesozoic age might be expected to be preserved in caves, like the fossil marsupials of Australia. The chances of preservation214 of the remains when once cemented into a fine breccia, or sealed down with a crystalline covering of stalagmite, are very nearly the same as those under which the Pleistocene animals have been handed down to us. The only reasonable explanation of the non-discovery of such remains seems to be, that the ancient suites215 of caves and fissures containing them, and for the most part near the then surface of the rock, have been completely swept away by denudation216, while the present caverns were either then not excavated or inaccessible.

Such an hypothesis will explain the fact that the no ossiferous caverns are older than the Pleistocene age, not merely in Europe, but in North and South America, Australia, and New Zealand. The effect of denudation in rendering217 the geological record imperfect, may be61 gathered from the estimate, which Mr. Prestwich has formed, of the amount of rock removed from the crests218 of the Mendips and the Ardennes, which is in the one case a thickness “of two miles and more,” and in the other as much as “three or four miles.”37 Under these conditions we could not expect to find a series of bone caves reaching far back into the remote geological past, since the caves and their contents would inevitably be destroyed.

The Filling up of Caves.

We must now consider the condition under which caves become filled up with various deposits. If the velocity219 of the stream in a water-cave be lessened220, the silt, sand, or pebbles it was hurrying along will be dropped, and may ultimately block up the entire watercourse. In bringing this to pass, however, the carbonate of lime in the water plays a most important part. If the excess of carbonic acid by which it is held in solution be lost by evaporation, it immediately reassumes its crystalline form, and shoots over the surface of the pool like plates of ice, or is deposited in loose botryoidal masses at their sides and on their bottoms; and, since the atmospheric water very generally percolates221 through the crannies in the rock, the sides and roof of the channel, above the level of the water, are adorned with a stony222 drapery of every conceivable shape. The rate at which this accumulation takes place depends upon the free access of air necessary for evaporation, and is therefore variable,—as in the case of the Ingleborough cave. In all the caves which I have examined62 there is a free current of air. If a water-channel becomes blocked up by either or both these causes, the joints and fissures in the rock offer an outlet to the drainage, more or less free, at a lower level, as in the Ingleborough cave, Poole’s cave, near Buxton, and many others. Sometimes, however, owing to the increased rain-fall, or to the obstruction223 of the lower channels, the water re-excavates the old passages, as we shall see to have been the case with the famous caverns of Kent’s Hole and Brixham. In the summer of 1872, a sudden rain-fall not merely opened out for itself a new passage into a swallow-hole close to Gaping Gill, on the flanks of Ingleborough, but forced its way out through the old entrance of the Ingleborough cave, breaking up the calcareous breccia, and removing the large stones in its course. A cave obviously may become dry, either by the drainage passing along a lower level, or by the elevation of the district by subterranean energy. After it has been forsaken224 by the stream, the particles brought down by the atmospheric water percolating through the joints, tend to fill it up on the surface, and these may be either of clay, loam225, or sand.

These actions may be studied in this country in the well-known caves of Ingleborough, Buxton, Cheddar, Wookey Hole, and a great many others in Derbyshire, Yorkshire, Staffordshire, Durham, Cumberland, and Wales.

The Cave of Caldy.

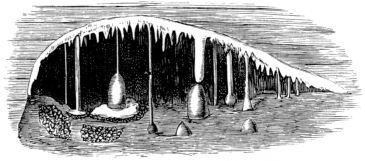

Fig. 9.—A View in the Fairy Chamber, Caldy.

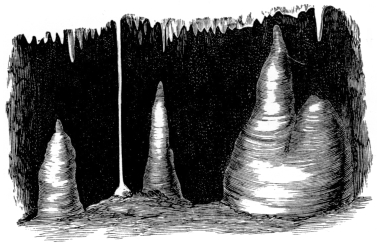

Fig. 10.—Stalagmites in the Fairy Chamber, Caldy.

Fig. 11.—The Fairy Chamber, Caldy.

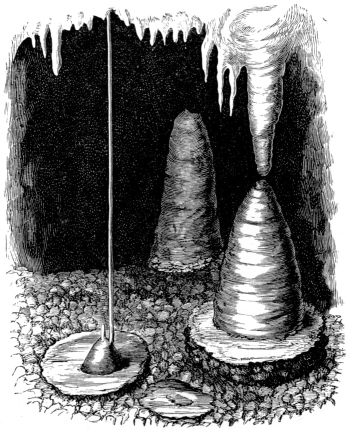

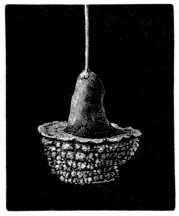

Among the most beautiful stalactite caverns in this country is that on the island of Caldy, immediately opposite to Tenby in Pembrokeshire, discovered some63 years ago in the limestone cliff, and explored by Mr. Ayshford Sanford and the Rev. H. H. Winwood, in 1866, and subsequently by the writer in 1871 and 1872. On creeping through a narrow entrance with an outlook to the sea on a precipitous side of a quarry226, a passage leads to a chamber of considerable horizontal extent, the bottom being covered with silt, on which stand pedestals of dripstone from an inch to two feet in length, each rising from a thin calcareous crust which does not altogether conceal227 the silt below. From it a low entrance leads into a fairy-like chamber, the floor consisting of a rich red, crystalline pavement, perfectly horizontal, and studded here and there with round64 bosses (Figs. 9, 10, 11), either red or snow-white. From the roof hang stalactites offering the same beautiful contrast of colours, forming a delicate canopy228 of tassels229, or passing downwards to the floor and constituting slender shafts about three feet long, and about the diameter of straws. Each of these is hollow, translucent, and more or less traversed by water, and in some places each stood next its fellow, almost as close as the straws in a cornfield. Sometimes the shaft stands on a cone230 (Fig. 11) of dripstone, more or less raised above the floor. Small pools of water occupy hollows in the pavement, each lined with glittering crystals of calcite (Fig. 12), which are slowly shooting over the surface, and converting some of the open hollows into bottle-shaped cavities65 (Fig. 13). Their sides and bottoms are covered with a crystalline growth of singular beauty, of which an idea may be formed by woodcut 14, which represents the edge. Where the drip happened to fall into a shallow pool, it gradually built up for itself a cone, on the lower portion of which the varying water-level is marked by horizontal rings of crystals (Fig. 15), and the normal waterline by the upper horizontal plate. Sometimes these were united to the roof by a slender straw-shaft. In Figure 11 the original shaft has been broken away, and as the direction of the drip has slightly shifted, a new one gradually descended, until finally it became cemented to the side of the cone.

Fig. 12.—Pools in Fairy Chamber.

Fig. 13.—Pool in Fairy Chamber.

Fig. 14.—Edge of Pool in Fairy Chamber.

Fig. 15.—Cone with Straw-column.

The history of these structures is very evident. The straw-like stalactites were formed by the evaporation of the carbonic acid from the surface of each drop of water, as it accumulated in one spot, and the consequent66 deposit of carbonate of lime around its circumference. It could not be formed in the centre, because of the continual movement of the successive drops in falling. By a circumferential231 growth of this kind a small crystal tube, of the diameter of a drop, is slowly developed, which continues to lengthen232 until the result is one of the straw-columns, with a hole in the centre for the passage of the water, which cannot readily part with its carbonic acid till it arrives at the end of the tube. Sometimes the hole has been subsequently blocked up by calc-spar, or the general surface been covered over with successive layers, until it becomes a mass of considerable diameter. If the drop fell into a deep pool, the straw-column was continued down to the water-line; if in shallow water, or on the floor, a pedestal was built up, as is represented in the preceding figures. The crystallization going on in the pools is greater at the surface than below, because of the greater evaporation, and consequently the stalagmitic film is gradually extending over it on every side from the edges (Figs. 12, 13).

As I broke my way into some of the unexplored recesses, through the thickly planted straw-shafts, and scene after scene of fairy beauty, unsullied by man, opened upon my eyes, the ringing of the fragments on the crystalline floor that accompanied almost every movement made me feel an intruder, and sorry for the destruction.

In some places, where the drip was continuous, and the calcareous basin which it had built up for itself shallow, small spherical233 bodies of calcite were so beautifully polished by friction in the agitated234 water, that they deserve the name of cave-pearls from their lustre235. In Fig. 16 I have represented a tiny basin with its pearly67 contents. Where the drip had ceased to be continuous each of these formed a nucleus for the deposit of calcite crystals, by which they were united to the bottom of the basin.

Fig. 16.—Basin containing Cave-pearls.

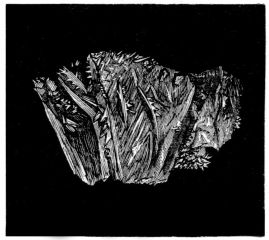

Fig. 17.—Fungoid Structures, magnified.

In the principal chamber in the cave, which is very nearly free from drip, the upper surfaces of the stones and stalagmites on the floor are covered with a peculiar fungoid-like deposit of calcite, consisting of rounded bosses, attached to the general surface by a pedicle (see Figs. 17, 18) sometimes not much thicker than a hair. They stood close together at various levels, following the inequalities of the surface of attachment236, and being on an average about 0·2 inch long. Several microscopical237 sections (Fig. 17) showed that each was formed originally on a slight elevation of the general surface, which would cause a greater evaporation of water than the surrounding portions, and therefore be covered with a greater deposit of calcite. This process would go on until the height was reached to which the water slowly passing over the general surface would no longer rise. Hence the remarkable uniformity of the height of the bosses. The evaporation is greater at the point furthest removed from the general surface, and therefore the apex is larger than the base (see Fig. 17). In Figure 18 they stand68 as thickly together as trees in a virgin30 forest, and are developed in greatest vigour238 where the small eminences239 cause a greater evaporation than the small depressions, and are stoutest240 and strongest at the free edges. Some of the pedicles, as in the figure, present traces of erosion, the outer layers having been eaten away by acid-laden water.

Some of these singular little bosses may have been moulded on minute fungi241, such as those in the cave of Ingleborough, but their presence is not revealed by the microscope.

The Black-rock Cave, near Tenby.

Fig. 18.—Fungoid Structure, Black-rock Cave.

I met with this remarkable kind of calcareous deposition242 in a second cave in the neighbourhood of Tenby. When examining the Black-rock quarries243 in 1871, the workmen pointed out a small opening which they believed to be the entrance of a cave, but which was too small for them to enter. By knocking off, however, a few sharp angles, I got into a small chamber about five feet high, with sides, roof, and bottom covered with massive dripstone. A few loose stones rested on the bottom. The whole surface, even including the stones upon the floor, one of which is figured (Fig. 18), was so completely covered with these peculiar fungoid bodies, that it was impossible to move without destroying hundreds of them. All were about the same height, 0·2 inches, snow-white,69 or of a rich reddish brown, and conformed to the unequal surface on which they stood. It is quite impossible to describe the effect of a whole chamber bristling244 with these peculiar structures. The only author by whom they are mentioned, Mr. John Beaumont—who described the caves of Mendip in 1680, considered them to be veritable plants of stone.38 The beautiful forms assumed by the dripstone in the caves of Caldy and Black-rock are by no means uncommon, but I have never met with them anywhere else in such perfection. They may be studied in all stalactitic caverns.

Great Quantity of Carbonate of Lime dissolved by Atmospheric Water.

A small portion only of the carbonate of lime is deposited as tufa or dripstone in the neighbourhood of the rock from which it has been derived, as compared with that carried by the streams into the rivers, and the rivers into the sea. An idea of this quantity may be formed from the calculation of the solid matter conveyed down by the Thames, given by Mr. Prestwich in his Presidential Address to the Geological Society in 1871, p. lxvii.

“Taking the mean daily discharge of the Thames at Kingston at 1,250,000,000 gallons, and the salts in solution at nineteen grains per gallon, the mean quantity of dissolved mineral matter there carried down by the Thames every twenty-four hours is equal to 3,364,286 lbs., or 150 tons, which is equal to 548,230 tons in the year. Of this daily quantity about two-thirds, or say70 1,000 tons, consist of carbonate of lime and 238 tons of sulphate of lime, while limited proportions of carbonate of magnesia, chlorides of sodium245 and potassium, sulphates of soda246 and potash, silica and traces of iron, alumina, and phosphates, constitute the rest. If we refer a small portion of the carbonates and the sulphates and chlorides chiefly to the impermeable argillaceous formations washed by the rain-water, we shall still have at least ten grains per gallon of carbonate of lime, due to the chalk, upper greensand, oolitic strata, and marlstone, the superficial area of which, in the Thames basin above Kingston, is estimated by Mr. Harrison at 2,072 square miles. Therefore the quantity of carbonate of lime carried away from this area by the Thames is equal to 797 tons daily, or 290,905 tons annually247, which gives 140 tons removed yearly from each square mile; or, extending the calculation to a century, we have a total removal of 29,090,500 tons, or of 14,000 tons from each square mile of surface. Taking a ton of chalk, as a mean, as equal to fifteen cubic feet, this is equal to the removal of 210,000 cubic feet per century for each square mile, or of 9/100 of an inch from the whole surface in the course of a century, so that in the course of 13,200 years a quantity equal to a thickness of about one foot would be removed from our chalk and oolitic districts.”

This destructive action, operating through long periods of time, destroys not merely the general surface of the limestone, but, where it is localized by the convergence of water, is capable of excavating248 the deepest gorges249 and the longest caves. The quantity of material carried away in solution is a measure of the power of carbonic acid in the general work of denudation.

71

The Circulation of Carbonate of Lime.

The circulation of carbonate of lime in nature presents us with a never-ending cycle of change. It is conveyed into the sea to be built up into the tissues of the animal and vegetable inhabitants. It appears in the gorgeous corallines, nullipores, calcareous sea-weeds, sea-shells, and in the armour250 of crustaceans251. In the tissues of the coral-zoophytes it assumes the form of stony groves252, of which each tree is a colony of animals, and in the wave-defying reef it reverts to its original state of limestone. Or, again, it is seized upon by tiny masses of structureless protoplasm, and fashioned into chambers of endless variety and of infinite beauty, and accumulated at the bottom of the deeper seas, forming a deposit analogous253 to our chalk. In the revolution of ages the bottom of the sea becomes dry land, the calcareous débris of animal and vegetable life is more or less compacted together by pressure and by the infiltration254 of acid-laden rain-water, and appears as limestone of various hardness and constitution. Then the destruction begins again, and caves, pot-holes, and ravines are again carved out of the solid rock.

The Temperature of Caves.

The air in caves is generally of the same temperature as the mean annual temperature of the district in which they occur, and therefore cold in summer and warm in winter. This would be a sufficient reason why they should be chosen by uncivilized peoples as habitations.

The very remarkable glacières, or caves containing ice instead of water, in the Jura, Pyrenees, in Teneriffe, Iceland,72 and other districts of high altitude and low temperature, in which the temperature even in summer does not rise much above freezing-point, may be explained by the theory advanced independently by De Luc and the Rev. G. F. Browne. “The heavy cold air of winter,” writes the latter, “sinks down into the glacières, and the lighter255, warm air of summer cannot on ordinary principles dislodge it, so that heat is very slowly spread in the caves; and even when some amount of heat does reach the ice, the latter melts but slowly, since a kilogramme of ice absorbs 79° C. of heat in melting; and thus when ice is once formed, it becomes a material guarantee for the permanence of cold in the cave. For this explanation to hold good it is necessary that the level at which the ice is found should be below the level of the entrance to the cave; otherwise the mere weight of the cold air would cause it to leave its prison as soon as the spring warmth arrived.” It is also necessary that the cave should be protected from direct radiation and from the action of wind. These conditions are satisfied by all the glacières explored by Mr. Browne.39 The apparent anomaly that one only out of a group of caves exposed to the same temperatures should be a glacière, may be explained by the fact that these conditions are found in combination but rarely, and if one were absent there would be no accumulation of perpetual ice. It is very probable that the store of cold laid up in these caves, as in an ice-house, has been ultimately derived from the great refrigeration of climate in Europe in the Glacial Period.

73

Conclusion.

In this chapter we have examined the physical history of caves, their formation, and their relation to pot-holes, cirques, and ravines; and we have seen that they are not the result of subterranean disturbance, but of the mechanical action of rain-water and the chemical action of carbonic acid, both operating from above. We have seen that cave-hunting is not merely an adventurous256 amusement, but also a quest that brings us into a great laboratory, so to speak, in which we can see the natural agents at work that have carved out the valleys and gorges, and shaped the hills wherever the calcareous rocks are to be found.

The rest of this treatise257 will be devoted258 to the evidence which they offer as to the former inhabitants, both men and animals, of Europe.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

volcanic

|

|

| adj.火山的;象火山的;由火山引起的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

cavern

|

|

| n.洞穴,大山洞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

caverns

|

|

| 大山洞,大洞穴( cavern的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

atmospheric

|

|

| adj.大气的,空气的;大气层的;大气所引起的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

shingle

|

|

| n.木瓦板;小招牌(尤指医生或律师挂的营业招牌);v.用木瓦板盖(屋顶);把(女子头发)剪短 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

inevitably

|

|

| adv.不可避免地;必然发生地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

cove

|

|

| n.小海湾,小峡谷 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

penetrate

|

|

| v.透(渗)入;刺入,刺穿;洞察,了解 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

formerly

|

|

| adv.从前,以前 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

inaccessible

|

|

| adj.达不到的,难接近的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

lava

|

|

| n.熔岩,火山岩 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

imprisoned

|

|

| 下狱,监禁( imprison的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

joints

|

|

| 接头( joint的名词复数 ); 关节; 公共场所(尤指价格低廉的饮食和娱乐场所) (非正式); 一块烤肉 (英式英语) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

joint

|

|

| adj.联合的,共同的;n.关节,接合处;v.连接,贴合 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

stratum

|

|

| n.地层,社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

laterally

|

|

| ad.横向地;侧面地;旁边地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

fissure

|

|

| n.裂缝;裂伤 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

grit

|

|

| n.沙粒,决心,勇气;v.下定决心,咬紧牙关 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

ridge

|

|

| n.山脊;鼻梁;分水岭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

fissures

|

|

| n.狭长裂缝或裂隙( fissure的名词复数 );裂伤;分歧;分裂v.裂开( fissure的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

mere

|

|

| adj.纯粹的;仅仅,只不过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

rhinoceros

|

|

| n.犀牛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

reindeer

|

|

| n.驯鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

rev

|

|

| v.发动机旋转,加快速度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

strata

|

|

| n.地层(复数);社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

limestone

|

|

| n.石灰石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

virgin

|

|

| n.处女,未婚女子;adj.未经使用的;未经开发的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

limestones

|

|

| n.石灰岩( limestone的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

minor

|

|

| adj.较小(少)的,较次要的;n.辅修学科;vi.辅修 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

celebrated

|

|

| adj.有名的,声誉卓著的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

subterranean

|

|

| adj.地下的,地表下的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

estuary

|

|

| n.河口,江口 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

feat

|

|

| n.功绩;武艺,技艺;adj.灵巧的,漂亮的,合适的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37