Definition of Historic Period.

In the preceding chapter the origin of caves has been discussed, as well as their relation to the physical geography of the districts in which they are found. We must now pass on to the biological division of the subject, which relates to the animals that they contain and the inferences that may be drawn6 from their occurrence.75 The caves will be divided into historic, prehistoric7, and pleistocene, according to the principles laid down in the first chapter.

It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to define with precision the point where legend ends and history begins; but the line may be drawn with convenience at the first beginning of a connected and continuous narrative8, rather than at the first isolated9 notice of a country. If we accept this definition, the historic period in Great Britain cannot be extended further back than the temporary invasion of Julius C?sar, B.C. 55, even if so far, since of the interval10 that elapsed between that event and the subjugation11 under Claudius, in the year A.D. 43, we know scarcely anything. Of the events which happened in this country before C?sar’s invasion there is no documentary evidence, although, by the modern method of scientific research, we are able to extend the narrative away from the borders of history far back into the arch?ological and geological past.

Wild Animals in Britain during the Historic Period.

During the historic period great changes have taken place in the animals inhabiting Great Britain. The wild animals have been diminished in number, and their area of occupation has been narrowed by the increase of population and the improvement in weapons of destruction. The brown bear, inhabiting Britain during the time of the Roman occupation, was extirpated12 probably before the tenth century. The current belief that it was destroyed in Scotland by the founder13 of the Gordon family in 1057 is unsupported by any documentary evidence which I have been able to discover;76 the crest14 of the Gordons, which is supposed to have been derived15 from the last of those animals slain16 in the island, consisting of three boars’, not bears’, heads. The last wolf is said to have been destroyed in Scotland in 1680, while in Ireland the animal lingered thirty years later to be a terror to the defenceless beggars. It was deemed worthy17 of a special decree for its destruction in the reign18 of Edward I. The wild boar was extinct before the reign of Charles I., while the beaver19, which was hunted for its fur on the banks of the Teivi in Cardiganshire during the time of the first Crusade, became extinct shortly afterwards. The stag was so abundant in the south of England as recently as the reign of Queen Anne, that she saw a herd20 of no less than five hundred between London and Portsmouth. At present the animal lives only in a half-wild condition, in the forest of Exmoor and the Highlands of Scotland; while the roedeer is now only found wild in Scotland, although it formerly22 ranged throughout the length and breadth of the country.

The reindeer23 is proved to have been living in Caithness as late as the year 1159, by a passage in the Orkneyinga Saga24.

The common rat, Mus decumanus, is the only wild or semi-wild animal that has migrated into this country during the historic period contrary to the will of man. In 1727 it (Pallas, Glires) had begun to invade Southern Russia from the regions of Persia and the Caspian Sea. Thence it swiftly spread over Asia Minor25, and while it was advancing to the west overland, it was carried by ships to nearly all the ports in the world. It arrived in Britain certainly before the year 1730, and has since nearly exterminated26 the black77 indigenous27 species. It is the only wild animal which is known to have invaded Europe since the pleistocene age, with the exception, perhaps, of the true elk28.

Animals living under the care of Man.

The fallow-deer, indigenous in the countries bordering on the Mediterranean29, was probably introduced by the Romans, since its remains occur in refuse-heaps of Roman age, such as that of London Wall, and of Colchester, while it has not been met with in older deposits. To them, also, we probably owe the introduction of the pheasant, which was sufficiently30 abundant in the neighbourhood of London in the time of Harold to be mentioned as one of the articles of food eaten on feast-days by the households of the Canons at Waltham Abbey in 1059. The domestic fowl31 has left the first traces of its presence in this country in the Roman refuse-heaps, although it was known to the Belg?, according to the testimony32 of C?sar, before the first Roman invasion.

The earliest mention of the domestic cat in this country is to be found in the laws of Howel Dha,40 that were probably codified33 at the end of the tenth or in the eleventh century, although many of the enactments34 may be of a much earlier date. The king’s cat is assessed at eightpence, or twice as much as that belonging to any subject. The ass41 was certainly known in Britain in the days of ?thelred (A.D. 866–871), when, according to Professor Bell, its price was fixed35 at the large sum of twelve shillings. The larger breed of cattle represented by the Chillingham ox, and descended36 from the great Urus,78 first appears in this country about the time of the English invasion. It gradually spread over those districts conquered by the English, until the small aboriginal37 dark-coloured, short-horn Bos longifrons, which was the only domestic breed in the prehistoric and Roman times, is now only to be met with in the hill country of Wales and of Scotland, in which the Brit-Welsh or Romano-Celtic inhabitants still survive.

Classificatory value of Historic Animals.

The principal changes in the fauna38 of Great Britain during the historic age are the extinction39 of the bear, wolf, beaver, reindeer, and wild boar, and the introduction of the domestic fowl, the pheasant, fallow-deer, ass1, the domestic cat, the larger breed of oxen, and the common rat; and as this took place at different times, it is obvious that these animals enable us to ascertain40 the approximate date of the deposit in which their remains happen to occur. And for this purpose the following table42 may be consulted:—

Animals Extinct.

A.D.

Brown bear circa 500–1000

Reindeer ” 1200

Beaver ” 11–1200

Wolf ” 1680

Wild boar ” 1620

Animals Introduced.79

Domestic fowl before 55 B.C.

Fallow-deer circa ”

Pheasant ” ”

Domestic ox of Urus type ” 449 A.D.

Ass ” 800–850

Cat ” 800–1000

Common rat ” 1727–30

Some or other of these animals are met with in the peat-bogs and alluvia, and in caves, but far more abundantly in the refuse-heaps left behind by man, by whom they have here been used either for service or for food.

The disappearance41 of certain wild species, from the areas in which they lived on the continent, in historic times, has not been ascertained42 so accurately43 as in this country, and many animals, which have become extinct in our restricted and highly-cultivated island, are still to be found in the continental44 forests, morasses45, and mountains. The brown bear is still to be met with in the Pyrenees, the Vosges, and in the wilder and more inaccessible46 portions of northern, middle, and southern Europe. The wolf still survives in France, and during the late German war preyed47 upon the slain after some of the battles. It, as well as the wild boar, ranges throughout the uncultivated regions of the continent. The beaver still lives in the waters of the Rhone, as well as in the rivers of Lithuania and of Scandinavia, and the reindeer, now restricted to the regions north of a line passing east and west through the Baltic, extended further south, in sufficient numbers to be remarked by C?sar, among the more noteworthy animals living in the great Hercynian forest, which overshadowed northern Germany in his days. This forest also afforded shelter to the true elk80 and the bison, both of which still live in Lithuania, as well as to the Urus, which was hunted by Charles the Great, near Aachen, and probably became extinct in the fifteenth or sixteenth century. The lion inhabited the mountains of southern Thrace in the days of Herodotus and of Aristotle, and became extinct in Europe between 330 B.C. and the days of Dio Chrysostom Rhetor (A.D. 100), who expressly says that there were no lions in Greece in his time. The panther also inhabited the same district when Xenophon wrote his “Treatise on Hunting.”

The fallow-deer was believed by the late Professor Edouard Lartet to have been introduced into France by the Romans. On a visit, however, to Paris in September 1873, Professor Gervais called my attention to an antler of the animal in the Jardin des Plantes, said to have been found in a refuse-heap along with axes of polished stone. It must therefore have lived in France in the Neolithic age, if it were obtained from an undisturbed deposit. It gradually spread into Germany and Switzerland, until in the eleventh century it was sufficiently abundant to be mentioned among the articles of food in a metrical grace of the monks49 of St. Gall50.

“Imbellem damam faciat benedictio summam.”43

The domestic fowl is to be recognized on Gallic coins before the Roman invasion, and therefore was probably known at the very dawn of Gallic history. The larger breed of oxen, descended from the Urus type, has been known in France, Germany, Lombardy, Scandinavia, and Switzerland, in the remote division of the prehistoric81 age known as the Neolithic.44 The buffalo51, on the other hand, of the Roman Campagna, was introduced into Italy, according to Paulus Diaconus, in the year 596, and the domestic cat,45 known to the Greeks from their intercourse52 with Egypt, became familiar to the eyes of the inhabitants of Rome and Constantinople as early as the fourth century after Christ.

It is evident from the survival of the wolf, the bear, beaver, reindeer, and the wild boar on the continent at the present time, that the chronological53 table which I have constructed for Britain is inapplicable to Europe in general. In the present state of our knowledge of the varying ranges of the animals, it seems impossible to form any similar scheme.

The historic caves are characterized by the presence of some of these animals, as well as of coins and pottery54, and other articles by which the date of their occupation may be ascertained.

The Victoria Cave, Settle, Yorkshire.

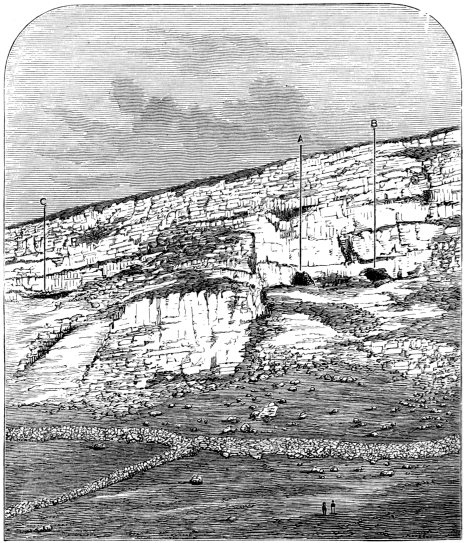

The most important historic cave in this country is that discovered by Mr. Joseph Jackson, near Settle, in Yorkshire, on the coronation day of Queen Victoria, in 1838, and which has therefore been called the Victoria Cave. It runs horizontally into the precipitous side of a lonely ravine known as King’s Scar (Fig55. 19), at a height of about 1,450 feet above the sea, according to Mr. Tiddeman, and it consists of three large ill-defined chambers56 filled with débris nearly up to the roof.

Fig. 19.—View of King’s Scar, Settle, showing the entrances of the Victoria and Albert Caves (from a photograph). A, B, Victoria; C, Albert.

The entrances face to the south-west, and open at the bottom of an overhanging cliff at the point where a scree, or accumulation of fragments from the cliff above, gradually slopes down to the bottom of the valley, about one hundred feet below. When Mr. Jackson made his discovery, he passed inwards through a small entrance,46 and was rewarded by finding in the earth on the floor a number of Roman coins, together83 with ornaments59 and implements60 of bronze, and some brooches of singular taste and beauty, with implements of bone, and large quantities of broken bones and fragments of pottery. The collection was very miscellaneous; for besides iron spear-heads, nails, daggers62, spoon-brooches of bone, spindle-whorls, beads64 of amber57 and of glass, there were bronze brooches, finger-rings, armlets, bracelets65, buckles67, and studs. All were lying pêle-mêle together, side by side with the broken bones of the animals, and the whole set of remains, with the exception of some of the brooches, was of the kind which is usually met with in the neighbourhood of Roman camps, cities, and villas68 which have been sacked.

The fragments of Samian ware69 and Roman pottery scattered70 through the mass, as well as coins of Trajan and Constantine, proved further, that the cave had been inhabited after the Roman invasion, and not earlier than the middle of the third century; and the rude imitations of Roman coins were, according to Mr. Roach Smith,47 probably in circulation for some centuries after the departure of the Romans from Britain.—“And although some of these remains are indicative of sepulture, yet from the evidence furnished there appears no positive proof of their having formed part of funereal71 deposits. A more satisfactory conclusion seems to arise in considering that these caves (i.e. the group) may have been used as places of refuge by the Romanized Britons during the troublous times at and after the close of the fourth century.” This conclusion we shall see fully72 borne84 out by the evidence subsequently obtained. Mr. Jackson gives the following account of the discovery:—

“The entrance was nearly filled up with rubbish, and overgrown with nettles73. After removing these obstructions74, I was obliged to lie down at full length to get in. The first appearance that struck me on entering was the large quantity of clay and earth, which seemed as if washed in from without, and presented to the view round pieces like balls of different sizes. Of this clay there must be several hundred waggon75 loads, but abounding76 more in the first than in the branch caves. In some parts a stalagmitic crust has formed, mixed with bones, broken pots, &c. It was on this crust I found the principal part of the coins, the other articles being mostly imbedded in the clay. In the other caves very little has been found. When we get through the clay, which is very stiff and deep, we generally find the rock covered with bones, all broken and presenting the appearance of having been gnawed78. The entrance into the inner cave has been walled up at the sides. In the inside were several large stones lying near the hole, any one of which would have completely blocked it up by merely turning the stone over. I pulled the wall down, and the aperture80 was now about a yard wide, and two feet high. On digging up the clay at about nine or ten inches deep, I found the original floor; it was hard and gravelly, and strewed81 with bones, broken pots, and other objects. The roof of the cave was beautifully hung with stalactites in various fantastic forms and as white as snow.”48

The interest in these discoveries led Mr. Denny, Mr. Farrer, and other gentlemen to examine the superficial85 stratum from time to time, until, in 1870, Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth, Mr. Walter Morrison, Mr. Birkbeck, and other gentlemen in the neighbourhood formed a committee for the investigation82 of the contents of the cave, which had been placed at their disposal by the courtesy of the owner, the late Mr. Stackhouse. They were aided by the assistance of Sir C. Lyell, Sir. J. Lubbock, and Mr. Darwin, Professor Phillips, Mr. Franks, and others, and by a grant obtained from the British Association, and have carried on the work since that time with comparatively little interruption. Mr. Jackson, the original discoverer, superintended the workmen; while I identified the works of art and the mammalian remains that were discovered, and drew up for the committee the reports brought before the British Association in 1870, 1871, and 1872, and before the Anthropological83 Institute in 1871. Mr. Tiddeman also contributed a report on the physical history of the cave, which is printed in the British Association Report for 1872, and subsequently in the Geological Magazine, January 1873.8649

The Romano-Celtic or Brit-Welsh Stratum.

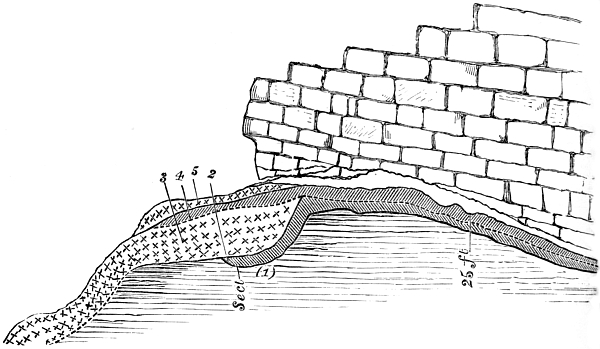

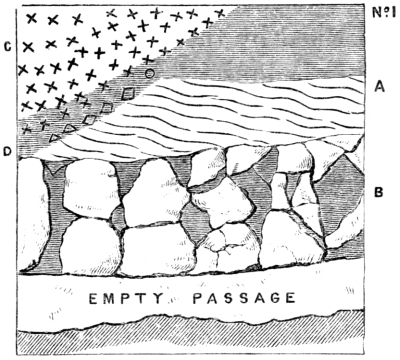

Fig. 20.—Longitudinal Section of Victoria Cave.

The committee resolved not to begin at the entrance which Mr. Jackson discovered in 1838 (Fig. 19 A), but to make a new passage, at a point where daylight could be seen through the chinks of the broken débris, which there prevented access. Ground was broken on a small plateau in front of this (Figs85. 19 B, 20), which, from the sunny aspect and commanding view, would naturally be chosen by the dwellers86 in the cave as their more usual place for eating and lounging, and in which we might therefore expect to find the remains of whatever they had dropped or lost. The gloomy recesses88 of a cave, indeed, even if lit up by large fires or by torches, are not fitted for any other purpose than for sleeping or concealment89; and if we add in this case the damp cold clay under foot and the constant drip of the water overhead, it was only reasonable to infer that most of their life was spent out of doors, and that the cave was used merely as a place of retirement90 for shelter. As the87 trench91 progressed we dug first of all through a thickness of two feet (Figs. 20, 21) of angular blocks of limestone92, that had fallen from the cliff above, and that rested on a black layer (No. 4) containing the kind of remains which we had expected. The layer was composed of fragments of bone and charcoal93, surrounding the burnt stones which had formed the ancient hearths94, and contained large quantities of the broken bones of animals which had been used for food, and coins and articles of luxury, as well as those instruments which were more naturally suited for the half-savage life of dwellers in caves. As we opened out the new mouth, the angular fragments disappeared and the black layer rose to the surface, composing the floor, and lying in some places beneath enormous blocks of limestone which had fallen from the roof since its accumulation, and being continuous with the layer in which Mr. Jackson first made his discoveries.

Fig. 21.—Vertical Section at the Entrance to the Victoria Cave.

It was evident that this stratum had been formed during the sojourn95 of man in the cave, and we shall88 find, in the examination of the remains which it furnished, proof that it is connected with the obscure history of Britain during the fifth and sixth centuries. We will take each group of objects in its proper class, beginning with what at first sight seems the least promising96, the broken bones of the animals that supplied the inhabitants with food.

The Bones of the Animals.

The bones of the Celtic short-horn (Bos longifrons) were very abundant, and proved that a variety of ox, indistinguishable from the small dark mountain cattle of Wales and Scotland, was the chief food of the inhabitants. A variety of the goat with simple recurved horns, which is commonly met with in the Yorkshire tumuli explored by Canon Greenwell, and in the deposits round Roman villas in Great Britain, furnished the mutton; while the pork was supplied by a domestic breed of pigs with small canines97; and since the bones of the last animal belong for the most part to young individuals, it is clear that the young porker was preferred to the older animal. The bill of fare was occasionally varied98 by the use of horse-flesh, which formed a common article of food in this country down to the ninth century. To this list must be added the venison of the roedeer and stag, but the remains of these two animals were singularly rare. Two spurs of the domestic fowl, and a few bones of wild duck and grouse99, complete the list of animals which can with certainty be affirmed to have been eaten by the dwellers in the cave. The numerous unbroken bones, some very gigantic, of the badger100, and those of the fox, wildcat, hare, and water-vole, commonly called water-rat,89 have probably been introduced subsequently, from those animals having used the cave as a place of shelter. There were also bones of the dog, which from their unbroken condition proved that the animal had not been used for food, as it certainly was used by the men who lived in the caves of Denbighshire in the Neolithic age. The whole group of remains implies that the dwellers in the Victoria Cave lived upon their flocks and herds101, rather than by the chase. And since the domestic fowl was not known in Britain until about the time of the Roman invasion, the presence of its remains fixes the date of the occupation as not earlier than that time. On the other hand, since the small Celtic short-horn (Bos longifrons) was the only domestic ox in use known in Roman Britain, and since it disappeared from those portions of the country which were conquered by the English, along with its Celtic possessors, the date is fixed in the other direction as being not much later than the Northumbrian conquest of that portion of Yorkshire. I shall return to this part of the subject presently; here I will only remark, that the present distribution of the lineal descendants of the Celtic short-horn, the small, dark-coloured Scotch102 and Welsh cattle, corresponds with those regions on which the Celtic population fell back before the English. And its survival in Wales, and until comparatively recently in Cornwall, Cumberland, and Westmoreland, may be accounted for by the fact, that in those districts the Celtic populations of Roman Britain were not displaced by the English invaders104.50

The larger breed of cattle known in its purity as the90 white ox of Chillingham, from which all our purely105 English breeds have been derived, was imported originally by the English, and spread over the whole country which they occupied, until at last the smaller and more ancient oxen survived only in a few isolated areas in the north and west of Britain. This displacement106 of the Celtic short-horn by the English oxen of the Urus type corroborates107, in a striking degree, the truth of Mr. Freeman’s view of the ruthless destruction of everything Roman and Celtic at the hands of the English. It is clear, therefore, that from the examination of the bones we may infer that the cave was occupied before the Celtic short-horn was supplanted108 in this district by the larger domestic breed of oxen, and after the introduction of the domestic fowl, that is to say, in the interval which elapsed between the Roman and English invasions.

We must now treat of the remains of man’s handiwork in the cave.

Miscellaneous Articles.

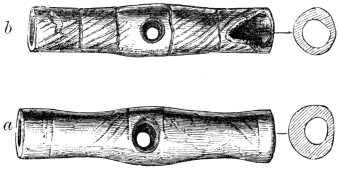

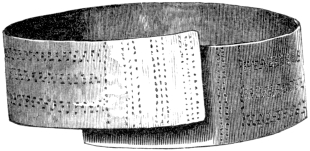

Fig. 22.—Spoon-brooch (natural size).

The ornaments and implements of bone consist of carefully smoothed pins, and points intended to be fitted to a handle, knife-handles made of bone and antler; three spindle-whorls made of the perforated head of a femur; a stud; a perfect spoon-shaped fibula (Fig. 22), which corresponds with one of those in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy, as well as several fragments, and which when in use was passed through holes in the clothes, in such a manner that the two ends alone were visible. These are ornamented109, and the shaft110 and the whole back is more or less polished by wear. Eight articles bear a close resemblance to the handles of gimlets (Figs. 23, 24), and most probably have been91 used as studs, or links, for fastening together clothing. The fact, indeed, that some have the central hole worn by the friction111 of a thong112 or string of some kind, coupled with the worn state of some of their surfaces, renders this guess very likely to be true. In Fig. 24, a, the ornament58 in right lines, which once covered the surface as in Fig. 24, b, is very nearly obliterated113 by friction against some soft body such as clothing. A reference to the figures will give a better idea of their shape and ornamentation than a mere79 description. Two perforated discs may have been used as studs. There are also many nondescript articles, consisting of sockets115 made of antler of stag, and bone rods carefully rounded, together with cut bones of uncertain use. For the identification of the ivory boss of a sword-hilt I am indebted to the kindness of Mr. Franks.

Besides the ornaments in bone and antler, there were seven glass beads, five transparent116 and two of a bluish tint117, and one of jet turned in a lathe118; as well as a fragment of a jet bracelet66. Among the articles of daily use were many rounded pebbles119, with marks of fire upon them, which had probably been heated for the purpose of boiling water. Pot-boilers, as they are called, of this kind are used by many savage92 peoples at the present day, and if we wished to heat water in a vessel120 that would not stand the fire, we should be obliged to employ a similar method. Other stones formed parts of ancient hearths, and two or three grooved121 slabs122 of sandstone had evidently been used for rounding and sharpening bone pins. The fragments of pottery were very abundant, and were all of the type usually found round Roman villas. One fragment of Samian ware was ornamented with the representation of a hunt.

Fig. 23.—Ornamented Bone-fastener (natural size).

Fig. 24.—Two Bone-links; a worn, b unworn (natural size).

This group of articles throws but little light on the date of the occupation of the cave. The Samian ware, and the ivory boss of a Roman sword, merely imply that it was either Roman or post-Roman.

93

The Coins.

If we turn now to the coins, we shall find the date to lie within narrower limits than those fixed by the animals. They consist of:—

Two silver of Trajan, d. 117.

Four bronze of Tetricus I., 267–274.

One bronze of Tetricus II., 267–274.

One bronze of Gallienus, d. 268.

One bronze of Constantine II., d. 343.

One bronze of Constans, d. 353.

Three barbarous imitations in bronze of coins of Tetricus, circa 400–500 A.D.

In a group of coins such as this the latest only give a clue to the date, since the earlier may have remained in circulation long after they were struck. In India, for example, those of Alexander the Great have not yet disappeared from the country, and in Spain, in the shops of Malaga, Moorish125, Roman, and even Ph?nician coins were current in 1863, as well as all those which have been struck since.51 We may therefore disregard the earliest coins, and fix our attention more particularly on those of the Constantine family, and the bronze minimi mentioned last in the list. The presence of the coin of Constans implies that the cave was occupied either during or after 337 A.D., when he ascended126 the throne; while the date of the minimi has not been ascertained with accuracy. “They abound77 upon all Roman sites, such as Verulam and Richborough. In size they come nearest to those struck under Arcadius and his successors, and I think that you will not be far wrong in assigning them to the first half of the fifth century.94 The latest of the genuine Roman coins found in this country are those of Arcadius and Honorius; at least, the finding of any of later date is quite exceptional. What the currency was between that time and the commencement of the Saxon coinage it is hard to say. It seems probable, however, that gold and silver had nearly disappeared, and that the needs of a small local commerce were supplied by the Roman copper127 coins of which abundance remained in the country, and by small pieces struck after their model, not improbably by private speculators.” This opinion, which Mr. John Evans, F.R.S., has been kind enough to write me, coincides with that of Mr. Newton, as well as that of Mr. Roach Smith; and we may therefore assume, with tolerable certainty, that the cave was inhabited during the first half of the fifth century or afterwards, at a time when the withdrawal128 of the Roman Legions had left the colony of Britain, whose youth and vigour129 had been consumed in the fierce struggle of the rivals for the throne of the West, a prey48 to the barbarian130 invaders.

It is of course conceivable that some of these coins may have been dropped at one time, and some at another, but nevertheless it seems very probable that the whole accumulation belongs to the same relative age. But whether this be accepted or not, it is certain the cave was inhabited during the time that the minimi were in circulation,—that is to say, during the first half of the fifth century, or from that time forwards.

The Jewellery, and its Relation to Irish Art.

This conclusion as to the date, derived from the coins, is confirmed in a remarkable131 degree by the examination of the articles of luxury. Besides two bronze brooches95 of the Roman pattern, known by arch?ologists as harp123-shaped (Coloured Plate, fig. 5), was one of the split-ring type, with a moveable pin, which is generally assigned to the later period of the Roman occupation of this country. One type of brooch was composed of two circular plates of bronze, soldered132 together, the front being very thin and bearing flamboyant133 and spiral patterns in relief (Fig. 25), of admirable design and execution. The original of the figure was discovered by Mr. Jackson, and is more perfect than any of those which we obtained in our excavations134. It is altogether unlike any Roman brooch properly so called, both in its composite make and style of ornament. A similar brooch has been discovered at Brough Castle, in Westmoreland, and was figured in the Proceedings136 of the Antiquarian Society (vol. iv. 129), by Sir James Musgrave, and a second is preserved in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy (492). The style corresponds with that of a medallion on a Runic casket of silver-bronze, figured by Prof. Stevens, and stated to have been obtained from Northumbrian Britain, as well as that of a brooch in the Museum at Mainz, assigned by the same authority to the third or fourth century. It is also to be met with in the illuminations of one of the Anglo-Saxon Gospels at Stockholm, as well as in those of the Gospels of S. Columban, preserved in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, and in the “Book of Kells” (8–900).52 In all these cases it cannot be96 affirmed to be Roman, and it is not presented by ornaments of either purely English or Teutonic origin. It is most closely allied137 to that work which is termed by Mr. Franks “late Celtic.” From its localization in Britain and Ireland, it seems to be probable that it is of Celtic derivation; and if this view be accepted, there is nothing at all extraordinary in its being recognized in the illuminated138 Irish Gospels. Ireland, in the sixth and seventh centuries, was the great centre of art, civilization, and literature; and it is only reasonable to suppose that there would be intercourse between the Irish Christians140 and those of the west of Britain during the time that the Romano-Celts, or Brit-Welsh, were being slowly pushed to the westward141 by the heathen English invader103. Proof of such an intercourse we find in the brief notice in the “Annales Cambri?,” in which Gildas, the Brit-Welsh historian, is stated to have sailed over to Ireland in the year A.D. 565. It is by no means improbable that about this time there was a Brit-Welsh migration142 into Ireland, as well as into Brittany.

Fig. 25.—Bronze Brooch (natural size).

Nor is it at all strange that the same style of ornament should occur in some few cases in North Germany.

“The conquest of Britain,” writes the Rev84. J. R. Green (“History of the English People,” p. 1653), “had thrust a wedge of heathendom into the heart of the Western Church. On the one side lay Italy and Gaul, whose Churches owned obedience143 to the see of Rome, on the other the free Celtic Church of Ireland. But the condition of the two portions of Western Christendom was very different. While the vigour of Latin Christianity was exhausted144 in a bare struggle for life, Ireland97 as yet unscourged by invaders had drawn from its conversion145 an energy such as it has never known since. Christianity had been received there with a burst of popular enthusiasm. Letters and arts sprang up rapidly in its train; the science and Biblical knowledge which had fled from the continent took refuge in famous schools which made Durrow and Armagh the universities of the West. The new life soon beat too strongly to brook146 confinement147 within insular148 bounds. Patrick, the first missionary149 of Ireland, had not been half a century dead, when Celtic Christianity flung itself with a fiery150 zeal151 into battle with the mass of heathenism which had rolled in upon the Christian139 world. Irish missionaries152 laboured among the Picts of the Highlands, among the Frisians of the northern seas; Columban founded monasteries153 in Burgundy and the Apennines; the canton of St. Gall still commemorates154 in its name the missionary before whom the spirits of flood and fell fled wailing155 over the waters of the Lake of Constance. For a time it seemed as if the course of the world’s history was to be changed, as if the older race that Roman and Teuton had swept before them had turned to the moral conquest of its conquerors156, as if Celtic and not Latin Christianity was to mould the destinies of the Churches of the West.”

It is impossible that Irish-Celtic art should not have made itself felt wherever the Irish missionaries penetrated157, and especially in the gorgeous illuminated Gospels, which it was the pride of S. Columban and his school to have made, and which now excite our wonder and admiration159. The early Christian art in Ireland grew out of the late Celtic, and was, to a great extent, free from the influence of Rome, which98 is stamped on the Brit-Welsh art of the same age in this country. The style, therefore, of these circular brooches, from its correspondence with that of the Irish illuminated gospels, affords reasonable grounds for the belief that the Victoria Cave was inhabited in the sixth century, or possibly later, but before the English invaders had swept the Brit-Welsh away from the district.

Two other brooches were also discovered in the black layer, which are even of greater interest than those which have just been described. The one represents a dragon (colored Plate, fig. 3), with its eye made of red enamel160; the other (colored Plate, fig. 7) shaped, like the letter S, has its front composed of an elaborate cloissonnée pattern in red, blue, and yellow enamels161, and is of the same design as two brooches in the British Museum, discovered, one near Whittington Hill, in Gloucestershire, and the other near Malton, in Yorkshire. All three were, undoubtedly162, turned out of the same artistic163 school, and they may have been made by one workman. The enamel, in all these examples, seems to have been inserted into hollows in the bronze, and then to have been heated so as to form a close union with them, and in some cases where it has been broken, as in colored Plate, fig. 7, small fragments still remain to attest164 the completeness of the fusion165 with the bronze. The style of workmanship is neither Roman nor Teutonic. An enamelled fibula with spirals in relief, found at Reichenbach54 (Soleure) in a post-Roman sepulchre, and figured by Bonstettin, is of a similar design, and it may be traced also in two brooches obtained by the Abbé Cochet, from the Merovingian Cemetery166 of99 Envermeu,55 although they are of more massive and square construction than those of Yorkshire.

One harp-shaped brooch (colored Plate, fig. 1) is ornamented with diamonds of blue enamel, separated by small triangles of red, and shows in its Roman design and Celtic ornamentation the union between Celtic and Roman art. A similar specimen167 from Brough Castle, Westmoreland, is preserved in the British Museum, and may have been turned out of the same workshop. We also met with an enamelled disk (colored Plate, fig. 6), and a finger-ring (fig. 4) of bronze-gilt, ornamented with blue enamel.

Several enamelled fibul? in the British Museum, obtained by Sir James Musgrave, at Kirby Thore, Westmoreland, belong to the same style of art as those of the Victoria cave, and were associated with the same class of remains. Shields,56 scabbards, horse trappings, and other articles have also been discovered in this county, decorated in the same fashion with coloured enamels, and especially a bronze vase from the late Roman tumuli, called the Bartlow Hills. They all belong to the class termed “late Celtic” by Mr. Franks, and are considered by him to be of British manufacture.

This view is supported by the only reference to the art of enamelling which is furnished by the classical writers. Philostratus, a Greek sophist, who left Athens in the beginning of the third century to join the Court of Julia Domna, the wife of the Emperor Severus, writes:—“It is said that the barbarians168 living in or by the ocean, pour these colors (those of the horse trappings)100 on heated bronze, that these adhere, grow as hard as stone, and preserve the designs that are made in them.”57 Mr. Franks’ opinion that this passage relates to Britain, seems to be more probable than that of the eminent169 French arch?ologist, M. de Laborde, who holds that it relates to Gaul and especially to “Belgica.”58

When we consider the variety of enamelled objects which have been discovered in the north of England, it seems to be by no means improbable that the principal centre of the art enamelling was here rather than in the south; and this conclusion is considerably170 strengthened by the fact that under the Romans political power centered in the district between the Humber and the Tyne, and that York, and not London, was the capital of Britain and the seat of the Roman Prefect. It is worthy of remark, that since the Emperor Severus built the wall which bears his name, marched in person against the Caledonians, and died at York, the account of the enamels may have been brought to the court of the Empress Julia from this very region, and thus come to be recorded by Philostratus.

Two harp-shaped fibul?, obtained by Mr. Jackson from the Victoria cave, and ornamented with enamel, are coated with silver, and in one of them two small blocks of that metal still remain firmly imbedded in the bronze. It is very probable that most of the ornaments were plated either with silver or gold, traces of which, in some cases, still remain.

Among the miscellaneous objects in metal are a bronze101 wire brooch (colored Plate, fig. 8), two bracelets, composed of twisted bronze-gilt wire; and one fragment in solid bronze, ornamented with right lines; one plain bronze finger-ring; two small buckles, respectively of bronze and of iron, and a small bronze flattened171 pin (colored Plate, fig. 2), ending in two points to which, at first, we were unable to assign a use. When, however, the two points were compared with the circles on the ornaments of bone (Fig. 22), there was but little doubt that this curious object was employed as a pair of fixed compasses. There were also iron articles which were too much corroded172 to admit of a guess at their probable use, besides a Roman key, knife-blades, and a spear-head discovered by Mr. Jackson.

The number of ornaments found in the Victoria Cave from time to time by various explorers is very considerable. They are scattered in the private collections of Messrs. Jackson and Eckroyd Smith, and in the Museums of Giggleswick Grammar-school, and of Leeds, and the British Museum.

Similar remains in other Caves in Yorkshire.

The Victoria cave is by no means the only one in the district that has furnished works of art and the remains of animals. The Albert cave (Fig. 19, c.) close by is, as yet, only explored sufficiently to prove that it contains the same kind of objects; and from that of Kelko, overlooking Giggleswick, they have been obtained by Mr. Jackson;59 as well as from that of Dowker-bottom between Arncliffe and Kilnsay, by Mr. James Farrer and Mr.102 Denny.60 From the last, seven spoon-shaped brooches of bone, and two spindle-whorls of Samian ware of the bottom of a vase, are preserved in the British Museum, as well as a bronze needle, and brooches both harp-shaped and discoid, and fragments of pottery. Three coins in bronze, according to Mr. Farrer,61 prove that the date of the accumulation is late or post-Roman, one being of Claudius Gothicus, whose reign ended A.D. 270, and two belonging to the Tetrici, A.D. 267–273, since they would remain in circulation for some time after they were struck. A bronze pin, in the possession of Mr. Jackson, from Dowker-bottom, is remarkable for the head being plated with silver.

The fragment of flattened antler from this cave, referred by Mr. Denny to the elk, most probably belongs to the crown of an old antler of the stag, and the remains of the “Canis prim173?vus” of that author cannot be distinguished174 from those of a large dog. The bones of the wolf, and an enormous stag in the Museum of the Philosophical175 Society at Leeds, are probably much older than the Brit-Welsh stratum.

These Caves used as Places of Refuge.

The presence of these works of art, in association with the remains of the domestic animals used for food, is only to be satisfactorily accounted for in the way proposed by Mr. Dixon. Men accustomed to luxury and refinement176 were compelled, by the pressure of some great calamity177, to flee for refuge, and to lead a half-savage life in these inclement178 caves, with whatever they could103 transport thither179 of their property. They were also accompanied by their families, for the number of personal ornaments and the spindle-whorls imply the presence of the female sex. We may also infer that they were cut off from the civilization to which they had been accustomed, since they were compelled to extemporize180 spindle-whorls out of the pieces of the vessels181 that they brought with them, instead of using those which had been manufactured for the purpose.

The evidence of History as to the Date.

We have already seen from the examination of the coins, that the Victoria cave was occupied during or after the first half of the fifth century, and from the works of art that it may have been, and probably was, occupied at a later time. To fix the latest possible limit to the occupation of the group of caves to which it belongs, we must appeal to contemporary history.

During the first four centuries of Roman dominion182 in Britain, the spread of the manners and arts of the great mistress of the world followed close upon her success in arms; and the policy of one of the greatest of her generals, Agricola, bore fruit in the adoption183 of her civilization by the British provincials184. The population clustered round the Roman stations, and cities sprang up, such as Chester, Bath, York, and Lincoln, between which a ready communication was maintained by the roads that still remain as monuments of engineering skill, and which, in many cases, have been used uninterruptedly from that time to the present day. Agriculture was carried on to such an extent, that Britain became one of the principal corn-producing regions of the Roman Empire; and a commerce with foreign countries was carried on from the ports on the104 banks of the Thames and the Severn (Gildas, i.). The mineral sources were also fully explored; tin was sought in the mines of Cornwall, lead in those of Derbyshire and Somersetshire, and iron in the forest of Dean, Sussex, and Northumberland. Nor was this material prosperity unaccompanied by the signs of luxury and culture. Numerous villas were dotted throughout the province, resembling in size and plan the quadrangle of a medi?val college at Oxford185 or Cambridge, and even in ruins astonishing us by their magnitude and the beauty of their tessellated pavements. York was the capital of the province and the centre of government, and consequently Yorkshire must have been, if anything, more completely penetrated with the Roman arts and civilization than any other part of Britain. The relation of the Roman conquerors to the conquered Celtic inhabitants was somewhat analogous187 to that which now exists between the English and the subject nations in India. Latin was the language spoken by the higher classes in the cities, of the army, and probably of the courts of law; while in the country the Celtic tongue held its ground, and still survives in the language of Wales. Christianity was probably professed188 in this country about the time of Constantine, and became the dominant189 religion by the middle of the fifth century, if not before.

Underneath190 all the outward signs of prosperity during the Roman rule in Britain, there were causes at work which ensured the ruin of the province. The policy of centralization, and the very perfection of the machinery191 for government on autocratic principles, which brought about the destruction of the Roman Empire, as in our own days they have nearly ruined France, bore fruit in Britain in the helpless apathy192 of the provincials when105 the machinery was broken up. It is therefore no wonder that when the Roman garrison193 was finally withdrawn194 from this country, in the year 409, the provincials were left an easy prey to their enemies. Nor need we wonder that they set up isolated centres of government, which we may term communes, in the year 410, in which each city stood out for itself, instead of combining together for the common weal. From this time forward the inhabitants of the Roman province of Britain, severed195 from the Roman Empire, became a prey to the many tyrants196 who sprang up, and the anarchy197 followed so pathetically described by Gildas. It was at this time that the coinage became debased, and Roman coins afforded the patterns for the small bronze minimi of the Settle cave,62 which are so abundant among the ruins of Roman cities in this country, such as St. Alban’s.

The invaders of Britain must now be considered. The Picts and Scots had secured a rude liberty under the protection of their mountains and morasses, rather than by their success in arms against the Roman legions, and their raids into the Roman province had been curbed198 by the walls and lines of forts, extending, the one from the Firth of Forth199 to the Firth of Clyde, the other from the Solway Firth to the Tyne. In spite of these, however, from time to time, in the fourth century, they carried desolation into Northumberland and Yorkshire, even if they did not penetrate158 farther into the south. And on the withdrawal of the Roman legions, at the beginning of the fifth century, their raids were organized on a much larger scale. In the pages of Gildas we have a melancholy200 picture of their results. In the letter written to106 ?tius, the Roman commander in Gaul, in 446, the Britains are described as sheep, and the Picts and Scots as wolves. “The barbarians drive us back to the sea; the sea drives us back again to perish at the hands of the barbarians,” are the words put into the mouth of the embassy.63 One plea for aid, which they advanced, is especially interesting, because it shows incidentally that the Roman civilization did not disappear with the withdrawal of the legions—the plea that unless they were succoured the name of Rome would be dishonoured201. Nerved by despair, the British in the following year take up arms, and, according to Gildas, leave their houses and lands, and taking shelter in mountains and forests, and in caves,64 succeed in driving back their Pictish and Scottish enemies.

It is very significant that caves should be mentioned in this account; for the region of Craven is one of the very few in the country in which they are sufficiently abundant to allow of their being used as places of shelter on a scale sufficiently large to be recorded in history; and when we consider that one of the natural highways from Scotland into central England lies through that district, it seems to me extremely probable that the group of caves of which Victoria is one is that referred to. On this point it is worthy of record, that in the year 1745, when the younger Pretender was at Shap, and it was doubtful whether he would take the route through Ribblesdale or by way of Preston, the eldest107 son of one of the landowners near Settle, was hidden, along with the family plate, in a Cave close to the Victoria, in the belief that the Highlanders were in the habit of eating children as well as of laying hands on the precious metals. The historical notice tallies202 exactly with the geographical203 position, and is not inconsistent with the evidence offered by the coins and other remains. The date, therefore, of the occupation may probably be assigned as about the middle of the fifth century.

This, however, is not the latest date that can be assigned. In the year 449, the three ships which contained Hengist and his warriors204, landed at Ebbsfleet, in Thanet, and the first English colony was founded among a people who were known to the strangers as “Brit-Welsh.”65 From that time a steady immigration of Angle, Jute, Saxon, and Frisian set in towards the eastern coast of Britain, as far north as the Firth of Forth, until, in the first half of the sixth century, the whole of the eastern part of our island was taken possession of by various tribes,66 whose names, for the most part, still survive in the names of our counties. The principal rivers also afforded them a free passage into the heart of the country, and the kingdom of Mercia gradually expanded until it embraced, not only the basin of the Trent, but reached as far as the line of the Severn. The river Humber afforded a base of operations for the Anglian freebooters, who founded the kingdom of Deira or modern Yorkshire; while the camp of Bamborough108 was the centre from which Ida, who landed with fifty ships in the year 547, conquered Bernicia, or the region extending from the river Tees to Edinburgh. The tide of English colonization205 rolled steadily206 westward, until, at the close of the sixth century, the hilly and impassable districts culminating in the Pennine Chain, and extending southwards from Cumberland and Westmoreland, through Yorkshire and Derbyshire, formed the barrier between the Brit-Welsh kingdoms of Elmet and Strathclyde on the east, and the English on the west. To the south of this the Brit-Welsh dominion was bounded by the river Severn, and included Chester and the whole of the basin of the Dee; while Somerset, Devon, and Cornwall, and the district round Bradford and Malmesbury formed the kingdom of West Wales.67

The long war by which the borders of England were gradually pushed to the west, at the expense of the Brit-Welsh, was one of the most fearful of which we have any record. The English invaders came over, with their wives and children and household stuff, in such force that the country which they left behind was left desolate207 for several centuries. Worshippers of Thor and Odin, and living a free life, equally divided between farming, hunting, and war, they were mortal foes208 to Christianity and to Roman civilization. They destroyed the Brit-Welsh cities with fire and sword; and the ashes of the Roman villas, which are to be found in nearly every part of the Roman province of Britain, testify to the keenness of their hate to everything which was at once Christian, Roman, and Celtic. Gildas forcibly describes the destruction which they wrought209 among his countrymen, by the metaphor210 that “the flame kindled109 in the east, raged over nearly all the land, until it flared212 red over the western ocean.”68 In the conquered districts the Brit-Welsh were either exterminated or enslaved, and their civilization was wholly replaced by the rude culture of the English.

It follows, from the nature of this conquest, that any group of remains, such as those in the caves under consideration, must be assigned to the time before the English had possession of the district, and we must therefore see what historical proof is to be found on the point.

At the close of the sixth century the Brit-Welsh kingdom of Elmet (in the basin of the river Aire)—a name which still survives in Barwick-in-Elmet, a little village about seven miles to the north-east of Leeds—extended over the country round Leeds and Bradford, passing westwards towards, if not into, Lancashire, and northwards probably so as to embrace Ribblesdale, and forming a barrier to the westward advance of the English possessors of eastern Yorkshire. Its downfall will give us the latest possible limit which we are seeking for the Brit-Welsh occupation of the Victoria Cave. The two kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia had united to form the powerful state of Northumbria, at the beginning of the seventh century, under ?thelfrith, who carried on the war against the Brit-Welsh with greater vigour than his predecessors213. In 60769 he marched along the line of the Trent, through Staffordshire, avoiding thereby214 the difficult and easily-defended hilly country of Derbyshire and110 East Lancashire, to the battle near Chester, famous for the destruction of the power of Strathclyde, and the death of the monks of Bangor, who fought against him with their prayers. By this decisive blow, the English first set foot on the coast of the Irish Channel, and Strathclyde and Elmet, on the one hand, were cut asunder215 from Wales. On the other Chester was so thoroughly216 destroyed that it remained in ruins for nearly three centuries, to be rebuilt by ?thelfl?d, “the Lady of the Mercians,” in 907, and the plains of Lancashire lay open to the invader.70 This western advance of the Northumbrians was completed by the conquest of Elmet, in 616, by Eadwine, and the whole district from Edinburgh, as far south as the Humber, and as far west as Chester, became subject to his rule.71 The latest possible date, therefore, that can be assigned for the occupation of these caves by the Brit-Welsh is determined217 by that event. It cannot be later than the first quarter of the seventh century, or the time when what remained of Roman art and civilization in that district was swept away by the ancestors of the present dalesmen. The relics218 in the caves must have been accumulated in the two centuries which elapsed between the recall of the legions in the days of Honorius and the English conquest. They are traces of the anarchy which existed in those times, and they tell a tale of woe219, wrought on the Brit-Welsh, by Pict, Scot, or Englishman, as eloquently220 as the lament221 of Gildas, or the mournful verses of Talliesin.111 They complete the picture of the desolation of those times revealed by the ashes of the villas and cities which were burned by the invaders.

We have now examined the evidence as to date offered by the contents of these caves, and we have seen that it agrees with the contemporary history. It may therefore be concluded that it lies in the fifth and sixth centuries, possibly the first quarter of the seventh.

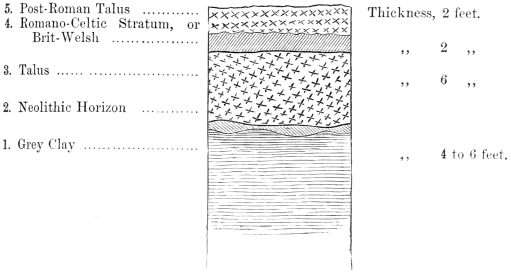

The Neolithic Stratum.

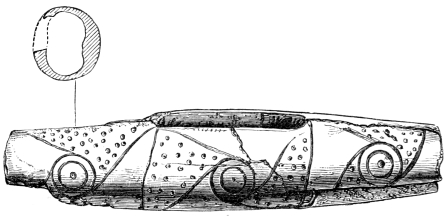

Fig. 26.—Bone Harpoon222 (natural size).

This occupation of the Victoria Cave by the Brit-Welsh is a mere episode in its history. It was inhabited by man in the neolithic age, at a time so remote that the interval between it and the historical period can only be measured by the rude method by which geologists223 estimate the relative age of the rocks. At the entrance the dark Romano-Celtic or Brit-Welsh stratum (Fig. 20, No. 4; Fig. 21, No. 4) lay buried, as we have seen, under an accumulation of angular fragments of stone which had fallen from the cliff. It rested on a similar accumulation (Fig. 20, No. 3; Fig. 21, No. 3) which was no less than six feet thick, and at the bottom of this, at the point where it was based on a stiff grey clay, a bone harpoon (Fig. 26) was discovered, as well as charcoal; a bone bead63 (Fig. 27), three rude flint flakes226, and the broken bones of the brown bear, stag, horse, and Celtic shorthorn (Bos longifrons). The harpoon is a little more than three inches long, with the head armed with two barbs227 on each side, and the base presenting a mode of securing attachment228 to the handle which has not before been discovered in Britain. Instead of a mere projection229 to catch the ligatures by which it was bound to the112 shaft, there is a well-cut barb124 on either side, pointing in a contrary direction to those which form the head. Ample use for such an instrument would be found in Malham tarn230, some three miles off, and very probably also in that which formerly existed close by at Attermire, but which has been choked up by peat, and is now turned into grass-land by drainage. The remains of the brown bear consist of numerous hollow bones and teeth, and the shaft of a femur with its articular ends broken off, has been polished by friction against some soft substance, so that its surface has a lustre231 like that of glass.

Fig. 27. Bone-bead (natural size.)

The question naturally arises, who were the ancient inhabitants of the cave whose rude implements occur in this lower stratum? From the few remains which we discovered, they were hunters and fishermen, and the possessors of domestic oxen, and possibly horses, and in a much lower state of civilization than the Brit-Welsh inhabitants who succeeded them in the cave after a long interval. There is no proof that they used a coinage, or that they were acquainted with metal. The conclusion that they were neolithic is based on the following evidence:—In 1871 the Exploration Committee examined a small cave about 200 yards off, in King’s Scar, and obtained the broken bones of the stag, Celtic short-horn (Bos longifrons), goat, and horse, a whetstone,113 and a rudely chipped scraper, to which, subsequently, Mr. John Birkbeck, jun., made the important addition of part of a human thigh-bone. This set of remains, the human thigh-bone excepted, agrees with those in the lower stratum in the Victoria Cave, not merely in the absence of metal, but also in affording signs of a comparatively rude civilization; and we might reasonably expect that the two caves so close to each other, would have been occupied by the same people at approximately the same time. If this be allowed, the thigh-bone may be assigned to one of these earlier inhabitants, the place of habitation being, as is frequently the case, subsequently used for purposes of burial. The thigh-bone itself is characterized by the great development of the muscular ridge186 known to anatomists as the linea aspera, implying the peculiar232 flatness of shin which is termed by Professor Busk platycnemism. This peculiar form has been met with in the neolithic tumuli of Yorkshire, explored by the Rev. Canon Greenwell, as well as in the human remains which I have discovered in the neolithic caves and chambered tombs of Denbighshire; and since it has not been observed in any human skeletons in this country which are not of that age, it may be fairly taken to prove that a neolithic people formerly lived in Ribblesdale. And further, since the traces of rude culture met with in these two caves are the same as those which characterize neolithic burial and dwelling233 places throughout Europe, they may be assigned to that remote age. Similar human remains were obtained by Mr. Farrer from the Dowker-bottom Cave, and imply that that cave also was used as a neolithic burial-place.

114 The identification of this race with the Basque or Iberian stock, from which are descended the small, dark peoples of Derbyshire, Wales, and certain parts of Ireland, must be referred to the chapters on the Neolithic Caves.

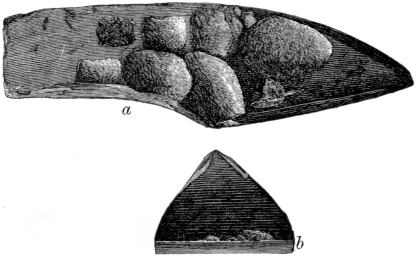

Fig. 28.—Stone Adze: a, side view; b, edge (natural size).

The reputed discovery of an adze (Fig. 28), of a variety of greenstone which Mr. Wyndham identifies with melaphyr, many years ago in the Victoria Cave, may offer additional evidence as to its having been occupied by a neolithic tribe. It was presented to the Museum of the Philosophical Society at Leeds by Mr. Jackson, and figured by Mr. Denny among the remains from the Caves of Craven, and presents characters that have not, to my knowledge, been met with in any other neolithic implement61 found in Great Britain: one end being roughly chipped for insertion into a socket114, while the other is carefully ground into a chisel234 edge. In these respects, as Mr. O’Callaghan and Mr. Denny have observed, it bears a striking resemblance to the stone adzes used by the South Sea Islanders, and especially in Tahiti;—a resemblance so strong that,115 unless it had been traced from the hands of the discoverer into the Museum at Leeds, it would be considered by many arch?ologists as an implement actually obtained from the South Seas. It may have been derived from the lower stratum, which furnished the equally peculiar harpoon, Fig. 26.

The Approximate Date of the Neolithic Occupation.

From the position in which these remains occurred, it is obvious that a neolithic tribe occupied the cave before the accumulation of the angular fragments, six feet in thickness (Fig. 20, No. 3; Fig. 21, No. 3), just as the date of the Brit-Welsh occupation is fixed as being after this, and before the accumulation of the two feet of débris above (No. 5). And in this we have a means of roughly estimating the interval of time between them. It is clear that the accumulation of two feet of angular fragments, torn away by the action of the weather from the cliff, has been formed in about 1,200 years, i.e. between the Brit-Welsh occupation and the present time. If it be admitted that equal quantities of the cliff have been weathered away in equal times, it will follow that the thickness of six feet between the Brit-Welsh stratum and that under examination was formed during a time thrice as long, or 3,600 years; and that consequently the date of the earlier occupation of the cave by man is fixed as being about 4,800, or 5,000 years ago. It is perfectly235 true, that in ancient times the frosts may have been more intense than they are now, and therefore that the rate of weathering may have been faster. To the objection that possibly a large mass of cliff may have tumbled down at one time, and subsequently116 been disintegrated236, it may be answered, that at the point at the entrance where the section was taken there was no evidence of any such fall; the angular blocks, both above and below the Brit-Welsh stratum, being as nearly as possible of the same size, and not lying with their faces parallel to each other, as would have been the case had they been disintegrated fallen blocks. Nevertheless this attempt to fix a date cannot lay claim to scientific precision, and in that respect is neither better, nor worse, than any other similar attempt founded on the rate at which a valley is being excavated237, or alluvium being deposited, or on the retrocession of a waterfall, such, for example, as Niagara. It is merely valuable as enabling us to form some sort of idea of the high antiquity238 of the neolithic men who left these remains behind in the cave.

As the trench (see Figs. 20, 21) begun on the outside passed into the entrance of the cave, the accumulation of stones above the neolithic stratum disappeared, and the latter became intermingled with the Brit-Welsh layer above, so that it would have been impossible to distinguish the one from the other had not the talus marked the interval in the plateau outside. The talus also above the Brit-Welsh stratum ceased at the entrance, although here and there large blocks of stone, fallen from time to time from the roof, rested on its upper surface.

The Grey Clays.

Immediately below the neolithic stratum, a deposit of stiff grey clay of unknown depth occupies both the entrance and the inside of the cave (Figs. 20, 21), containing fragments of limestone and large angular blocks117 which had fallen from the roof. A shaft sunk to a depth of twenty-five feet near the entrance failed to arrive at the bottom, but presented the following section in descending240 order: stiff grey clay with layer of stalagmite six feet thick; a finely laminated calcareous clay twelve feet thick; and below, a similar bed of clay to that on the surface. In a second shaft sunk to the depth of twelve feet farther within the cave, the base of the grey clay was not reached.72

Fig. 29.—Section below Grey Clay at entrance.

A third shaft, at the entrance, however, penetrated the clay, No. 1 of Figs. 20, 21, 29, at a depth of about five feet, and revealed the existence below of a reddish-grey loamy cave-earth (Fig. 29, A), containing bones and teeth of the same animals as those from the caverns118 of Kent’s Hole, Wookey Hole, and others, which belonged to a group that invaded Europe before the glacial period, and that inhabited the region north of the Alps and the Pyrenees in pre- and post-glacial times.73

We subsequently discovered the cave-earth to be from three to four feet thick, and that it rested on an accumulation (Fig. 29, B) of large blocks of limestone, the interstices between which were filled with clay, sometimes laminated and at others homogeneous, as well as with coarse sand. Below this we broke into an empty passage, one side of which was formed by the solid rock, and the other of blocks of stone imbedded in the clay.

As we opened out a horizontal passage towards the cave-earth, A, from the outside, the talus (Fig. 29, C) of angular débris was cut through first, which gradually became more and more clayey in its lower portions: at one point, D, there were several glaciated blocks, some imbedded in clay and others perfectly free. It rested obliquely243 on the edges of the cave-earth, and passed gradually at the entrance into the clay occupying the interior of the cave.

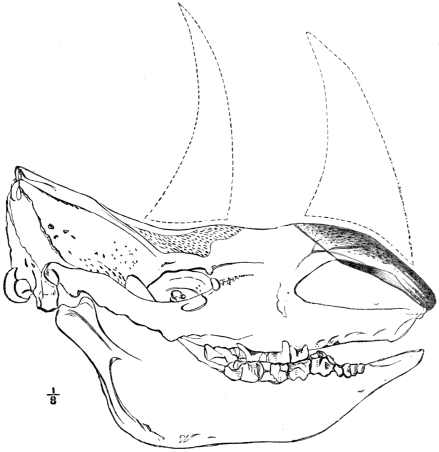

The Pleistocene Occupation by Hy?nas.

The remains of the spel?an variety of the spotted244 hy?na were very abundant in the cave-earth, consisting of fragments of skulls246, jaws248, and bones, and especially of coprolites, which formed irregular floors, accumulated during successive occupations of the cave by that animal. All the bones were gnawed and scored by119 teeth, the lower jaws were without the angle and coronoid process (see Fig. 92), and the hollow bones which contain marrow249 were broken, while those which were solid and marrowless250 were for the most part perfect: and this held good, not merely of the remains of the hy?na, but of those of all the animals which constituted their prey. The bones, for example, of the woolly rhinoceros251 are represented merely by the hard distal portion of the shaft of the humerus, and of the solid bones of the ulna and radius252, while the only portions of skull245 are the solid pedestal offered by the nasal bones on which the front horn was supported, and a few smaller fragments. The pedestal in question is depicted253 by the dark shaded portion of120 Fig. 30, the outline of the skull and lower jaw247 being taken from one of Professor Brandt’s plates of the Woolly Rhinoceros found in Siberia.74 The teeth which imply the presence of the mammoth254 (milk molars 3 and 4) were those of a young individual, as is very generally the case in caves which have been occupied by hy?nas. The young would naturally be more exposed to the attack of those cowardly beasts of prey than the adult, armed with its long curved tusks255, and defended, not merely by its thick skin, but also by the covering of wool and long hair which is peculiar to the species. Besides these animals, the reindeer, red-deer, bison, horse, the brown, grizzly256, and great cave bears, were preyed upon by the hy?nas and dragged into the cave. All these species were discovered within an area of a few square yards of cave-earth, which passes into the interior of the cave under the grey clay. They belong to that well-defined group known as pleistocene, quaternary, or post-pleiocene, which was proved to have inhabited Yorkshire75 in ancient times from Dr. Buckland’s discoveries in Kirkdale, and Mr. Denny’s examination of the river-deposit at Leeds, in which the remains of the hippopotamus257 were obtained.

Fig. 30.—Skull of Woolly Rhinoceros, showing the part which is not eaten by the hy?nas.

The last and most important addition to this fauna is that of man, a fragment of fibula in the same mineral condition as the rest of the pleistocene bones, having been identified by Professor Busk with an unusually massive recent human fibula. Although the fragment is very small, its comparison with the abnormal specimen in Professor Busk’s possession removes all doubt121 from my mind, as to its having belonged to a man, who was contemporary with the cave-hy?na and the other pleistocene animals found in the cave.

The probable Pre-glacial Age of the Pleistocene Stratum.

Is this occupation of the Victoria Cave by the pleistocene mammalia pre-glacial or post-glacial?—before, or after, the great lowering of the temperature in northern Europe? This difficult question can only be answered by an appeal to the physical history of the clay and cave-loam241, and to the evidence as to glacial action in the district, and to the distribution of the mammalia in Great Britain during the pleistocene period. Glaciers258 have left their marks in nearly every part of Lancashire and Yorkshire, and especially in the neighbourhood of the Victoria Cave. The hill-sides around are studded with large ice-borne Silurian rocks; boulder-clay occupies nearly every hollow on the elevated plateaux; and moraines are to be observed in nearly every valley. At the entrance of the cave itself, ice-scratched Silurian grit-stones are imbedded in the clay, which abuts260 directly on the cave-loam, and passes insensibly into the clay, with angular blocks of limestone within the cave. They may possibly be the constituents261 of a lateral262 moraine in situ, as Mr. Tiddeman suggests, or they may merely be derived from the waste of boulder-clay which has dropped from a higher level.

The latter view seems to me to be most likely to be true, because some of the boulders263 have been deprived of the clay in which they were imbedded, and are piled on each other with empty space between them, the clay122 being carried down to a lower level and re-deposited. Their position, however, on the edges of the cave-earth implies, in any case, that they had been dropped after its accumulation.

There is another point to be considered in the physical evidence. The deposits above the cave-earth, occupying the interior and entrance of the cave, have been introduced by the rains, either through the entrance, or through the crevices264 which penetrate the roof, and consist of a finer detritus265 washed out of the boulder-clay on the surface at a higher level. The cave-earth, however, although it has been introduced in the same way, cannot be accounted for on the supposition that it was derived from the boulder-clay, with which it contrasts in the fact that it is a loam, of a reddish grey colour, containing a large percentage of carbonate and phosphate of lime.

Similar deposits, characterized by their red colour, are to be found in nearly all the caves of the south of England, in France, and southern Europe, not complicated, as here, by the glacial phenomena266 of the district. Had the layer been formed in the Victoria Cave, from the destruction of the boulder-clay, it would have been identical in composition with the deposits above.

The laminated portions of the grey clay are considered by Mr. Tiddeman to have been formed by the flow of water through the entrance, derived from the daily melting of the glacier259 which occupied the valley in ancient times, and he compares it with a similar lamination in the boulder-clay at Ingleton, which has been described by Mr. Binney in the neighbourhood of Clifton, near Manchester, under the expressive267 name of “book-leaves.” Since, however, similar accumulations123 are being formed at the present time at the bottom of pools in many caves, as, for example, in that of Ingleborough, they cannot be taken to imply a glacial origin. They are not found merely in one spot in the Victoria Cave, but are scattered, more or less, through the general mass of the clay, and occur abundantly even below the cave-earth, having been deposited in the interstices between the large blocks of limestone. In these positions they are of uncertain age, and there is no reason why some of the hollows which we discovered below the cave-earth (Fig. 29, B) should not be filled with them at the present time by the heavy rains. They dip at all angles, and are conformable to the surfaces on which they have been dropped.

The most important argument in favour of the pre-glacial age of the mammaliferous cave-earth is afforded by the range of the animals in Great Britain during the time that certain areas were occupied by glaciers. In a paper read before the Geological Society in 1869, I showed that those areas in Great Britain in which the marks of glaciers were the freshest and most abundant coincided with those which were barren of the remains of the pleistocene mammalia, and I therefore inferred that this was due to the fact, that the areas in question were covered by ice at the time that pleistocene animals were so numerous in the caves, and river-deposits of southern and eastern England, and on the continent. In a map published in 1871, Cumberland, Westmoreland, Lancashire, and the greater portion of Yorkshire are represented as being one of these barren areas, in which no pleistocene mammalia have been observed. It is obvious that the hy?nas, bears, mammoths, and other creatures found in the pleistocene124 stratum, could not have occupied the district when it was covered by ice; and had they lived soon after the retreat of the ice-sheet, their remains would occur in the river-gravels, from which they are absent throughout a large area to the north of a line drawn between Chester and York, whilst they occur abundantly in the glacial river deposits south of that line. On the other hand, they belong to a fauna, that overran Europe, and must have occupied this very region before the glacial period, since their remains have been found in pre-glacial strata268 to the north in Scotland, to the south at Selsea, and to the east in Norfolk and Suffolk. It may, therefore, reasonably be concluded that they occupied the cave in pre-glacial times, and that the stratum in which their remains lie buried, was protected from the grinding of the ice-sheet, which destroyed nearly all the surface accumulations in the river-valleys, by the walls and roof of rock, which has since, to a great extent, been weathered away.76 This view is also held by Mr. Tiddeman.

The exploration of the Victoria Cave, which has hitherto yielded such interesting evidence of three distinct occupations—first by hy?nas, then by neolithic men, and lastly by the Brit-Welsh, is by no means complete. The cave itself is of unknown depth and extent, and the mere removal of so much earth and clay as it is at present known to contain will be a labour of years. The results of the exploration, up to the present time, are of almost equal value to the arch?ologist, to the historian, and the geologist224, and prove how close is the bond of union between three branches of human thought which at first sight appear125 remote from each other. The discussion of the problems connected with the neolithic and pleistocene strata must be referred to the fifth and following chapters.

The Kirkhead Cave.

Other caves in this country, besides the group under consideration in Yorkshire, have been occupied by the Brit-Welsh. That known as the Kirkhead Cave, on the eastern shore of the Promontory269 of Cartmell, on the northern shore of Morecambe Bay, explored by Mr. J. P. Morris,77 and a Committee of the Anthropological Society in 1864–5, contained remains of the same type as those of the Brit-Welsh stratum in the Victoria Cave. In the débris which formed the floor and extended to an unknown depth below, a coin of Domitian, “a trefoil-shaped Roman fibula,” a pin, ornamented with green enamel, and a bronze ring were discovered in association with broken remains of domestic animals—Bos longifrons, pig and goat, dog and horse, as well as stag, roe21, wild goose, and many human bones. A bronze celt and a spear-head were also found, at a depth respectively of five and six feet, and a flint flake225 at a depth of seven feet; and fragments of pottery, a bead of amber, cut bones, the perforated head of the femur, and other articles. From this group of remains it may be inferred that the cave was occupied by the Brit-Welsh, and before them by the users of bronze, and possibly by a neolithic people, and that it had at some time or another been used as a place of burial. Just inside the entrance, which overlooked the sea at a height of 45 feet, a semi-circular breastwork of large126 stones rendered the cave habitable, and capable of easy defence.

Mr. Morris’s view that the discovery of a bronze celt, flint flakes, and coins in this cave proves that all three were in use at the same time, and by the same people, is not borne out by the published account of the excavation135. There is no proof that the deposit had not been disturbed, or that the articles were not dropped at different times. And in support of this conclusion, it may be advanced, that there is no case on record of the discovery of bronze celts or swords along with any Roman coins under conditions which would prove that they were in use at the same time. Had such been the case the ruins of the many Roman villas and cities, destroyed by the English, would have furnished some examples. At Silchester, even such a rare article as a Roman eagle has been met with. There is every reason to believe with Sir John Lubbock, Mr. Evans, and other eminent arch?ologists, that the use of bronze for weapons had been superseded270 by that of iron before the dawn of history in this country. It is otherwise with the flint flakes; since my discovery of several inside a Roman coffin271 at Hardham, near Pulborough, in Sussex, in a cemetery that belongs to the later portion of the Roman dominion in Britain, proves that they were used for some purpose at that time.78

Poole’s Cave, near Buxton.

In the collection of articles obtained from Poole’s Cave, in Buxton, in Derbyshire, I identified, in 1871, in company with Mr. Pennington, bronze Roman coins, minimi, Samian and other ware, and large quantities of127 broken bones of the same animals as those from the Victoria Cave. A bronze harp-shaped fibula of the type of Fig. 5 of the coloured Plate is inlaid with silver, and is so perfect that it might still be used.

Thor’s Cave, near Ashbourne.

A cave also, in Staffordshire, four miles from Ilam, explored by the Midland Scientific Association in 1864,79 under the supervision272 of Mr. Carrington, has furnished articles of the same kind as those of Yorkshire. It is known as Thor’s cave, and penetrates273 the lofty cliff of limestone, on the south side of the river Manifold, at a height of about 254 feet from the bottom of the valley, and about 900 feet above the sea, running horizontally inwards, and being divided inside by a row of buttressed274 columns into two noble gothic aisles275. Its bottom was occupied by clay, in which, near the entrance, there were thick layers of charcoal at depths of two, three, and four feet below the surface, mingled239 with broken bones and pottery, that indicated the spots where fires had been kindled211. The articles discovered were as follows:—