Changes of Level in the Mediterranean area in Meiocene and Pleiocene Ages.—Bone-caves of Southern Europe.—Of Gibraltar.—Of Provence and Mentone.—Of Sicily.—Of Malta.—Range of Pigmy Hippopotamus3.—Fossil Mammalia in Algeria.—Living Species common to Europe and Africa.—Evidence of Soundings.—The Glaciers4 of Lebanon.—Of Anatolia.—Of Atlas6.—Glaciers probably produced by elevation7 above the Sea.—Mediterranean Coast-line comparatively modern.

In the preceding chapter we have seen that north-western Europe was elevated, during the pleistocene age, to an extent of at least 600 feet above its present level; so that Ireland was united to Britain, and Britain was joined to the mainland of Europe, proof of this elevation being dependent upon the soundings on one hand, and the distribution of the fossil mammalia on the other. Such a change must necessarily have affected8 the whole physical conditions of the area, since the substitution of a mass of land for a stretch of sea, and the higher altitude of the land, would tend to produce climatal extremes of considerable severity. It is indeed no wonder that during this time of continental9 elevation, the hills of369 Wales, Yorkshire, Derbyshire, Cumbria, and Scotland should be crowned with glaciers, or that there should have been a migration10 to and fro of animals, comparable to that which is now going on in Siberia and the northern portions of North America. The condition of southern Europe at that time has a most important bearing on any conclusion which may be drawn11 as to the pleistocene climate in France, Germany, or Britain. For if it be proved that the Mediterranean Sea was then smaller than it is now, the greater land-surface would increase both the heat of the summer and the cold of the winter in central and north-western Europe.

Changes of Level in Mediterranean area in Meiocene and Pleiocene Ages.

The geological evidence that the Mediterranean region has been subjected to oscillations of level during the tertiary period, is clear and decisive. Prof. Gaudry241 has proved, in his work on the fossil remains12 found at Pikermi, that the plains of Marathon, now so restricted, must have extended in the meiocene age far south into the Mediterranean, so as to afford pasture to the enormous troops of hipparions and herds13 of antelopes14, the mastodons and large edentata, revealed by his enterprise. The rocky area of Attica, as now constituted, could not have supported such a large and varied16 group of animals, nor could the broken hills and limestone17 plateaux have been inhabited by hipparions and antelopes, if their habits at all resembled those of their descendants living at the present time. It may, therefore, reasonably be concluded370 that Greece, in those times, was prolonged southwards, and united to the islands of the Archipelago by a stretch of land. If Africa were then as now the head-quarters of the antelopes, it is very probable that one of the lines by which they passed over into Europe, and spread over France and Germany, was in this direction. Nevertheless, it must be admitted that the changes of level, which have taken place since the meiocene age in those regions, are so complicated as to render it almost impossible to restore the meiocene geography.

In the succeeding, or the pleiocene age, the presence of the African hippopotamus in Italy, France, and Germany, can only be accounted for by a more direct connection with the African mainland than is offered by a route through Asia Minor19. It would seem, therefore, that the Mediterranean Sea could not then have formed the same barrier to the northern migration of the animals which it does now. In many regions, however, the present land was then sunk beneath the sea, and marine20 strata21, of pleiocene age, were accumulated in the Val d’Arno, Sicily, and southern France.

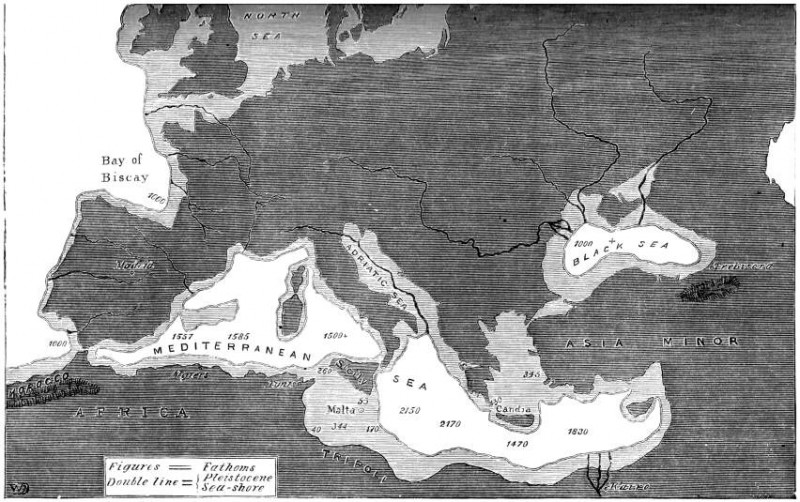

The physical geography242 of the Mediterranean in the pleistocene age may be ascertained22 with considerable accuracy by the distribution of the animals, coupled with the evidence of the soundings.

Bone-caves of Southern Europe.

The mammalia in the bone-caves of southern Europe differ from those of the region north of the Alps and Pyrenees in the absence of the arctic species, and the371 presence of some which are of a more strictly23 southern type. Nevertheless, the influence of the mountains in lowering the temperature in their neighbourhood is to be traced in the presence of the remains of certain animals. Thus, in the caves of Gibraltar we find an ibex, which cannot be distinguished24 from those of the Spanish sierras, and in Mentone and Provence, a marmot, specifically identical with that of the Alps.

The bone-caves in the neighbourhood of the Mediterranean afford most important testimony25 as to the geographical26 changes which have taken place, since the animals found in them lived in that region. We will take those of the Iberian peninsula first.

Caves of Gibraltar.

Ossiferous caverns28 have long been known to occur in the fortified29 rock of Gibraltar,243 but were not examined scientifically until the year 1863, when the researches of Captain Brome, Prof. Busk, and Dr. Falconer, proved that pleistocene species were buried in considerable numbers in its cavities and fissures30. Of these the most important is the great perpendicular32 fissure31 in Windmill Hill, called the Genista cave, which has been traced down to more than a depth of 200 feet. From the upper portion were obtained the polished stone implements33, human skulls34, and other neolithic35 remains described in the sixth chapter, p. 204, which prove that Gibraltar was inhabited by the Basques in the neolithic age, while the remains from the lower revealed the presence of a singularly mixed group of animals.

372 The fossil bones have been referred by Prof. Busk and Dr. Falconer to the following species:—

Lepus cuniculus, rabbit.

Felis leo, lion.

F. pardus, panther.

F. caffer.

F. pardina, lynx.

F. serval, serval.

Ursus ferox, grizzly36 bear.

Canis lupus, wolf.

Equus caballus, horse.

Rhinoceros37 hemit?chus.

Capra ibex, ibex.

Sus scrofa, wild-boar.

Cervus elaphus, red deer.

C. capreolus, roe38.

C. dama, fallow deer.

The spotted39 hy?na, the serval, and Felis caffer, are species now peculiar40 to Africa, and it is obvious that they could not have found their way into Gibraltar under the present physical conditions of the Mediterranean. Elephants and rhinoceroses41 could not have lived on so barren and treeless a rock, unless it had overlooked a fertile plain, nor would the carnivora have chosen it for their dens42, had it then been cut off from the feeding-grounds of the herbivores. Their presence, therefore, as Dr. Falconer justly remarks, implies the existence of land now sunk beneath the waves, but then extending southwards to join Africa.

To the African animals, mentioned above as inhabiting the Iberian peninsula in the pleistocene age, M. Lartet has added the African elephant (E. Africanus) and the striped hy?na (II. striata), which have been found in a stratum43 of gravel44 near Madrid along with flint implements.244 None of the purely45 arctic mammalia, such as the reindeer46, musk47 sheep, or woolly rhinoceros, so abundant in France, Germany, and Britain, have been met with south of the Pyrenees.

373

Bone-caves of Provence and Mentone.

The arctic animals are also absent from the numerous bone-caves and bone breccias of Provence and Mentone. The pleistocene fauna of Provence consists, according to M. Marion,245 of the spotted hy?na, and lion, Elephas antiquus or straight-tusked elephant, Rhinoceros hemit?chus, wild-boar, urus, stag, horse, and rabbit. The breccias in the island of Ratonneau have also furnished the porcupine48, brown bear, and tailless hare. Man is proved to have been living in the district at the time by the discovery of perforated and cut bones, in the cave of Rians.

The fissures and caves of Mentone, explored by Mr. Moggridge246 in 1871, and subsequently by M. Rivière, contained a fauna composed, according to Prof. Busk, of the following species:—

Marmot.

Field-vole.

Lion.

Panther.

Lynx.

Wild-cat.

Spotted hy?na.

Wolf.

Fox.

Brown bear.

Cave-bear.

Roe.

Stag.

Ibex.

Urus.

Horse.

Wild-boar.

Rhinoceros hemit?chus.

Along with these were large quantities of charcoal50 and flint flakes51, which proved that man had inhabited the district while the deposits were being formed.

374 Mr. Moggridge gives the following account of the results of his exploration:—247

“The caves of the red rocks, half a mile out of Mentone, are in lofty rocks of jurassic limestone on the shore of the Mediterranean, and at an average height of 100 feet above that sea, the rocks themselves attaining52 an elevation of 260 feet. They have now been repeatedly rifled by the learned or the curious; but when the principal cave (Cavillon) was nearly intact, the author made a section of it from the modern or highest floor, down to the solid rock. There were five floors formed in the earth by long-continued trampling54; on each, and near the centre, were marks of fire, around which broken bones and flints were abundant, except upon the lowest, where but few bones occurred, and no flints. The bones were those of animals still existing. Few implements were found, but many chips of flint, some cores and stones used as hammers. Perhaps this cave was used as a place for manufacturing flints, which must have been carried from their native bed, distant about one mile.

“There is nothing to evince the action of water; on the contrary, the numerous stones that occur are all angular.... Below these caves a slope of about 180 feet descends55 to the edge of the sea. Through the upper part of this slope, at distances from the cave of from 0 to ten feet, is a railway cutting 600 feet long, fifty-four feet deep, and sixty feet above the sea. The mass removed in making this cutting was composed of angular stones not waterworn. Loose at the surface, it soon became a more or less mature breccia, for the most part so hard that it was blasted with gunpowder56.” In this breccia, and at various depths, some of more than thirty375 feet, the author has taken out teeth of the bear (Ursus spel?us) and of the hy?na (Hy?na spel?a) while with and below those teeth he found flints worked by man.

The subsequent exploration by M. Rivière248 has resulted in no important addition to the fauna: the famous human skeleton having been, as I have already remarked in the seventh chapter, interred57 in the pleistocene strata, and probably not pal53?olithic. It may possibly be of the era of the upper floors described by Mr. Moggridge, in which all the remains belong to living species.249

This cave-fauna is more closely related to that of southern Europe than to that north of the Alps and Pyrenees. The striped hy?na found in the cave of Lunel-viel, Hérault, by Marcel de Serres, along with the reindeer and other animals, probably belongs to the same southern group.

Bone-caves of Sicily.

Certain members of the African fauna are also proved to have ranged northwards over Europe in the direction of Sicily, by the discoveries in the caves of that island. The Sicilian bone-caves have been worked for the sake376 of the bones since the year 1829; and of these many shiploads were sent to Marseilles from San Ciro, belonging, according to M. de Christol, principally to the hippopotamus. In 1859,250 Dr. Falconer examined the collections made from this cave, as well as those which remained in situ, and carried on further researches into a second in the neighbourhood, known as the Grotto58 di Maccagnone, and in the following year two others were discovered and explored in northern Sicily by Baron59 Anca. The species were as follows:—

Homo, man.

Felis leo, lion.

Hy?na crocuta, spotted hy?na.

Ursus ferox,251 grizzly bear.

Canis.

Cervus, deer.

Bos, ox.

Equus, horse.

Sus scrofa, boar.

Elephas antiquus.

Elephas Africanus, African elephant.

Hippopotamus major, hippopotamus.

Hippopotamus Pentlandi.

Lepus.

The presence of man was indicated by charcoal and flint flakes.

The African elephant was obtained from three caves: from that of San Teodoro, by Baron Anca; from Grotta Santa, near Syracuse, by the Canon Alessi; and from a cave near Palermo, by M. Charles Gaudin. It is obvious that the presence of this animal, as well as of the spotted hy?na, in Sicily can only be accounted for on the hypothesis that a bridge of land formerly60 existed, by which they could pass from their head-quarters, that is to say Africa. On the other hand the presence of the grizzly bear, and of the Elephas antiquus implies that they377 passed over into Sicily, from their European headquarters, before the existence of the Straits of Messina, since both animals are abundant on the mainland of Europe. The larger species of hippopotamus, doubtfully referred by Dr. Falconer to the H. major (= H. amphibius), may have crossed over either from Italy, where its remains are very abundant in the pleiocene and pleistocene strata, or from Africa.

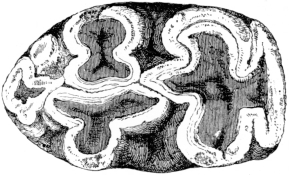

Fig62. 127.—Molar of Hippopotamus Pentlandi (1/1). (Sicily.)

A small species of hippopotamus, H. Pentlandi, Fig. 127, occurs in incredible abundance in the Sicilian caves. It bears the same relation, in point of size, to the fossil variety of the African hippopotamus, as the living H. liberiensis does to the latter.

Bone-caves of Malta.

The bone-caves of Malta were first scientifically explored by Admiral Spratt, in 1858, and subsequently by Dr. Leith Adams, and others. The Maghlak Cave near the town of Crendi, contained large quantities of the Hippopotamus Pentlandi, together with the gigantic dormouse, named Myoxus Melitensis. A short distance off a second cavern27, explored by Dr. Leith Adams, contained numerous remains of at least two species of pigmy378 elephant about the height of a small horse. Its small size may be gathered from the accompanying woodcut (Fig. 128) of the last lower true molar, taken from the lithograph63 published in Dr. Falconer’s “Pal?ontographical Memoirs,” vol. ii. pl. xii.

Fig. 128.—Molar of Elephas Melitensis, Malta (2/3). (Falconer.)

Range of Pigmy Hippopotamus.

The pigmy hippopotamus has lived also in other districts in the Mediterranean region. One of its teeth, now preserved in the British Museum, was discovered by Dr. Leith Adams, in Candia. In 1872 I identified in the Oxford64 Museum a last lower true molar, which extends the range of this species to the mainland of Europe. It was obtained by Dr. Rolleston from a Greek tomb at Megalopolis65, in the Peloponese, and was probably derived66 from one of the many caves in the limestone of that district. For this extinct animal to have spread from Sicily to Malta, from Malta to Candia, and from Candia to the Peloponese, or vice67 versa, these three islands must have been united to the Peloponese and have been the higher grounds of land, now submerged beneath the waves of the Mediterranean.

The view therefore, advanced by Dr. Falconer and Admiral Spratt, that Europe was connected with Africa379 by a bridge of land, extending northwards from Sicily, is fully61 borne out by an examination of the fossil remains both of that island and of Malta (see Fig. 129).252

Fossil Mammalia in Algeria.

If the African mainland extended to Europe in the direction of the Straits of Gibraltar, and of Malta and Sicily, so as to afford passage for the African mammalia into Europe, it would equally afford passage for the southern advance into Africa of some of the European mammalia. Evidence of this we meet with in a stratum of clay at Mansourah, near Constantine, in Algeria, described by M. Bayle in 1854.253 The animals which he obtained, consisting of the ox, antelope15, hippopotamus, and elephant, have been described by Prof. Gervais. An examination of his figure of a fragment of a molar tooth leaves no room for doubt, that the Elephas meridionalis was living in north Africa during the pleistocene age; that is to say an extinct animal, the head-quarters of which are to be found in Italy, ranged as far south as northern Africa.

Living Species common to Europe and Africa.

The former continuity of Africa by way of the Iberian peninsula and Sicily, may also be inferred by the distribution of the mammalia at the present time. Prof. Gervais254 observes that most of the insectivora are380 the same in Europe and north Africa. The genette and ferret (F?torius furo), the Mangousta Widdringtoni (Gray), and the fallow deer, are common to Spain and Africa. The porcupine of Algeria belongs to the same species as that of Italy and Sicily, and the wild boar does not present any characters of importance by which it can be separated from that of Europe. From the present range, therefore, of the mammalia the same conclusion may be drawn as to the continuity of Africa with Europe as is afforded by their distribution in the pleistocene age.

Evidence of Soundings.

These conclusions derived from the study of the mammalia, are corroborated68 and supplemented by the evidence of the soundings. As we enter the Straits of Gibraltar (Fig. 129) the Atlantic Ocean shallows, until between Tangiers and Tarifa it is not more than from 270 to 300 fathoms69. Between Tarifa and Ceuta the sea measures from 300 to 400 fathoms, and thence, in passing eastwards70, suddenly deepens to the extent of over 1,500 fathoms. An elevation of 400 fathoms would be quite sufficient to raise a barrier of land between Morocco and Spain, and to insulate the deep Mediterranean basin from the Atlantic. The soundings between Sicily and Tunis are 260 fathoms; between the former place and Malta, 55 fathoms; between Malta and the African mainland, 34·4 fathoms. An elevation of 400 fathoms would suffice therefore to connect Africa with Sicily, and to insulate the eastern from the western Mediterranean depths. To the east of Sicily the soundings reveal a depth of over 2,000 fathoms, and this deep381 basin extends as far to the east as Cyprus and Asia Minor. Between Candia and the Peloponese, the sea is 460 fathoms deep. An elevation therefore from 400 to 500 fathoms would allow of the passage of Hippopotamus Pentlandi from Candia to the Peloponese, and thence by southern Italy into Sicily and Malta. I have therefore represented in the map what would be the necessary result of the elevation of the bottom of the Mediterranean to that extent. Two great barriers of land would unite Africa with Spain and Italy, and enable the African mammalia to find their way into the regions north of the Mediterranean Sea. The shallowness of the sea at those two points indicates the existence of the sunken barriers. The African elephant however did not pass far northwards, since it has only been met with in Spain and Sicily.

Fig. 129.—Physiography of Mediterranean in Pleistocene Age.

Such a change in level as this would convert the Adriatic into dry land, and cause the islands of the Grecian Archipelago to rise high above the surrounding plains. The 500-fathom line is therefore taken to represent the probable sea margin71 of the pleistocene age, although in centres of volcanic72 activity, such as Sicily and the Archipelago, local changes of level, even of greater magnitude, may have taken place.

This view of the former elevation of the Mediterranean area to a height of from two to three thousand feet above the present level will go far to explain the remarkable73 traces of glaciers discovered in Syria, Anatolia, and Morocco.

The Glaciers of Lebanon.

Dr. Hooker, in his journey to Syria in 1860, discovered that the cedars74 of Lebanon grew principally on one383 spot, on old moraines which traverse the head of the Kedisha valley. This valley terminates in broad, shallow, open basins at a height of about 6,000 feet above the sea, resembling the corries of the Highlands; and one of these, in which the cedars grew, was divided into two distinct flats by a transverse range of ancient moraines from 80 to 100 feet high and with perfectly75 defined boundaries. “The rills from the surrounding heights collect in the upper flat, and form one stream, which winds among the moraines on its way down to the lower flat, whence it is precipitated76 into the gorge77 of the Kedisha. The cedars grow on that portion of the moraine which immediately borders this stream, and nowhere else; they form one group about 400 yards in diameter, with an outstanding tree or two not far from the rest, and appear as a black speck78 in the great area of the corry and its moraines, which contain no other arborious vegetation, nor any shrubs79, but a few berberry and rose bushes that form no feature in the landscape.”255

In ancient times, therefore, the glaciers descended81 to a height of about 6,000 feet above the sea, and were fed by the perennial82 snow-fields of the crest83 of Lebanon.

The Glaciers of Anatolia.

The former presence of glaciers at nearly the same altitude has also been proved by the travels of Mr. Gifford Palgrave in Anatolia,256 especially in the valley through which the Chorok flows, and in the mountainous country to the north-east, between Georgia and the384 Black Sea. The river Chorok runs about 120 miles in a north-easterly direction, and is separated from the Euxine by a mountain chain reaching a height of 11,000 feet, thus forming a long strip of land, which is called Lazistan after its inhabitants, a tribe of Lazes. It then turns suddenly to the north, where it falls into the sea. The southern side is determined84 by mountains of Cretaceous, Jurassic, and Plutonic rocks, which form the watershed85 between the tributaries86 of the Black Sea and Persian Gulf87. Three large moraines are to be found on the southern side of the valley, their lower extremity88 about 5,000, their upper origin nearly 8,000 feet above the sea. No moraines are seen where the chain does not reach an altitude of 7,000 feet, though angular boulders89 are not uncommon91. The upper mountain contours are invariably rounded, and smoothed off, and the sides are scooped92 too widely for the depressions to have been caused by water. Low down in the valley the slopes terminate in rifted precipices93.

That these moraines were posterior to the volcanic eruptions94 in the district, is evident from the examination of a broad stone ridge49, near the highest point to the east of Erzeroum, where at a height of 7,000 feet the Jurassic limestone was interrupted by a volcanic outbreak of several miles in extent. Traces of a crater95 were visible. Above, the granite96 peaks rose to a height of 9,000 feet; below, a wide moraine crossed the road, composed of volcanic fragments mixed with granite. Consequently, it must have been formed after the volcano had become extinct. Similar traces are to be found at Keskeem Boughaz. Mr. Palgrave concludes “that the ice-cap of the north-eastern Anatolian watershed, in post-pleiocene (pleistocene) times, must have reached downwards97, on385 the northern side of the range, to 7,000 feet above the present sea-level, while some of the glaciers issuing from it descended to about 4,500 of the same measurement.” Striated98 and ice-worn boulders, especially of granite, were very abundant. This region, it must be observed, is within sight of the lofty granite range of Tortoom, which is “streaked with perpetual snow.”

After leaving the Chorok valley and getting on to the watershed, at a distance of fifty miles to the north-east, Mr. Palgrave reached the main ridge or backbone99 of the land. Here, among the limestone ledges100, about 6,400 feet above the sea, is a colossal101 moraine, formed of worn granite blocks, partly overgrown with forest, and descending102 from a height of over 8,000 feet. It is divided, by a valley, from a lofty undulating granite plateau that is scooped out here and there into deep oval lakes, always full of blue water. The sides of the plateau are strewn with boulders of granite, brought from the higher peaks about five miles off. These boulders occur in greater or less abundance down to the basin of the Ardahan, near the sources of the Kur or Cyras, which joins the Araxes before flowing into the Caspian. The height of this Ardahan basin is about 6,500 feet; it is, but for a slight easterly slope, a water level. The bottom consists of deep alluvial103 soil mixed with detritus104 and boulders; the sides are rounded and smoothed, and bear every mark of long ice-covering. These plateaux, studded with lakes, stretch east to Russo-Georgia, till their greatest height is gained at Kel Dagh, a mountain about 11,000 feet high: thence they descend18 to the plains of Georgia and the Black Sea.

No glacial marks have been observed on the seaward side of the range, except at Hamshun in the Lazistan386 mountains, between the River Riom and Trebizond. Here, at 6,900 feet, is a granite-strewn plateau, thinly green with grass, sheltered from the sea by lofty peaks on the north-west, and backed to the south-east by tremendous jagged granite cliffs, the highest 12,500 feet above the sea. The plateau itself is about forty miles in length, irregular in breadth, its surface rounded and jotted105 over with boulders. But just as my track led near under the base of Verehembek, at an altitude of 8,300 feet, it crossed a large broad moraine, descending from the higher slopes, and having its base in a broad bare valley not far below, which showed that here, at the highest and widest part of the Lazistan chain, perpetual ice had once existed in sufficient quantity to furnish at least one glacier5. From this case it seems that the limited ice-cap of the Hamshun highlands extended no further down than 8,500 or 9,000 feet, thus differing by a line of from 1,000 to 2,000 feet from the glacial covering of the inland range.

The Glaciers of the Atlas Mountains.

Similar traces of glaciers have been observed in the Atlas mountains by Mr. George Maw,257 in his travels in Morocco with Dr. Hooker and Mr. Ball in 1871. “After four hours’ continued ascent,” he writes (p. 19), “the termination of the glen comes into full view, and we observe with great interest that it is closed by a group of moraines, proving the former existence of glaciers in the Atlas, and confirming my opinion that the great boulder90 beds flanking the chain are also of387 glacial origin. Two villages, probably the highest in the Atlas, are built on the principal moraine; Eitmasan, at its base, at a height of 6,000 feet, and Arroond, near its summit, at a height of 6,800 feet; the terminal angle of the larger moraine having a vertical106 height of 800 feet. It is composed of immense blocks of porphyry, lying at a steep angle of repose107, up which it takes us nearly an hour to climb. The existence of these moraines in latitude108 30?° N. (the latitude of Alexandria) is perhaps the most interesting fact we noticed during our journey, for this is the most southerly point at which the evidence of extinct glaciers has been observed, and tends to confirm the opinion entertained by many geologists109, that the refrigeration during the glacial period was almost Universal.”

Glaciers probably the result of elevation above the Sea.

The elevation of the African moraines above the sea, of about 6,000 feet and upwards110, is nearly the same as those of Asia Minor. If the mountains of the Atlas, Lazistan, and Lebanon shared in the upward movement of the Mediterranean area, the addition of 3,000 feet to the height could not fail to leave marks behind of the low temperature thereby111 caused. It is very probable, that during the time the Mediterranean was reduced to two land-locked seas, these mountains were covered with snow-fields, and constituted the ice-sheds of glaciers.

From the range of the mammalia we have inferred the existence of land barriers, extending across from Africa to Spain and Italy, and from Candia to Greece, and their actual existence beneath the sea has been proved by388 soundings, which necessitate112 an elevation of from 400 to 500 fathoms to bring them above the sea-level. We have also seen that the higher mountains, which most probably participated in this upward movement, bear traces of a lower temperature in the moraines of the Atlas and Lazistan. The hypothesis of such an elevation during the pleistocene age may therefore be taken to be proved so far as it explains two widely different classes of facts, the distribution of the mammals and the existence of glaciers where they are now unknown.

The physical condition of the Mediterranean area, in the pleistocene age, may be summed up as follows. The mainland of Africa extended northwards to join Europe, in the direction of Gibraltar and Italy. The islands of Malta and Sicily were hilly plateaux, overlooking an undulatory plain. Corsica and Sardinia were joined to Italy, Majorca and Minorca to Spain, Candia to Peloponese, and Cyprus to Asia Minor. The area now occupied by the Adriatic Sea constituted the lower valley of the Po, and the Archipelago was a plain studded with volcanic cones113; and at the same time glaciers crowned the higher mountains of northern Africa and of Asia Minor.

The substitution of land for a stretch of sea, in the Mediterranean, could not fail to cause the summer heat to be more intense in the region to the north than at the present time, while the increased elevation would produce a greater severity of winter cold, as Mr. Godwin Austen has pointed114 out in the case of the hills of Devonshire. When, indeed, we consider that the pleistocene land surface extended from the snowy heights of Atlas, as far north as the 100-fathom line off the coast of Ireland, we might expect to find African animals, such as the spotted hy?na and Felis caffer, ranging as389 far north as Yorkshire, for the only barrier to their migration would be that offered by the severity of a pleistocene winter.

Mediterranean Coast-line comparatively modern.

The submergence of the barriers, and the constitution of the Mediterranean as we find it now, have probably taken place but a short time ago, from the geological point of view, though we know that for the last 3,000 years the coast-line has been on the whole unchanged, except from the silting115 out of the sea by the sediment116 of rivers, such as the Po, and the elevation and depression of small areas by volcanic energy, as at Santorin. The physical character of the shores testifies to the truth of this view.

“On entering the Straits of Gibraltar,” Mr. Maw writes, “from the Atlantic, a notable change takes place in the aspect of the coast. Cape80 St. Vincent, on the Atlantic coast, presents a bold line of cliffs to the sea, and bluff117 cliffs extend many miles towards the Straits; but as soon as these are passed, a change of coast-form takes place, which must be noticeable to every observer. Cliffs on the sea-board become the exception, and the general line of the coast is merely a shelving under the sea of the general hill-and-valley system of the land, the sea running up all the depressions, and the land elevations118 spreading out into the sea with scarcely any abrupt119 cliff-line of demarcation. The uneven120 sea-bottom of the Straits seems to be a continuation of the contour of the adjacent land, consisting of rolling alternations of hill and valley, which must have received its conformation by subaerial agencies.”

390 “Corsica, and the adjacent islands of Elba, Capraja, and Monte Christo, are also remarkable for the absence of cliffs, and are wanting in those abrupt escarpements separating land and water which are so abundant on our own coasts. Their aspect is that of mountain-tops rising out of the sea, suggesting to the eye the seaward prolongation of their subaerial contour of sloping hillsides and river-cut valleys, as though the sea had not stood sufficiently121 long at its present level to excavate122 an escarpement. The deep intersecting bays that occur along the coast from Marseilles to the Riviera suggest the same conclusion, the undulating land surface spreading down to the water’s edge, and the deep bays running up the intervening valleys, which must have had an origin common with that of their landward prolongations.”

It is impossible to shut our eyes to the full force of this reasoning. The present aspect of the Mediterranean is, geologically speaking, a thing of yesterday.

Changes of Level in the Sahara coincident with those in the Mediterranean.

But if the Mediterranean area has been depressed123 to an amount of from 2,000 to 3,000 feet since the pleistocene age, we have proof that the region to the south has been elevated to that extent in comparatively modern times. Mr. Maw,258 in his journey in 1873 to the Northern Sahara, observed raised beaches at a height of 2,000 feet, and loam124 and shingle-beds as high as 2,700 feet. He therefore concludes that the part of the Sahara which he explored had been raised at least 3,000 feet above the sea. These changes of level, the same in amount, but391 in opposite directions, were probably compensatory and simultaneous. Northern Africa may have been cut off from the central and southern portions of the continent by the sea extending over the Sahara, during the time that the Mediterranean was represented by the two inland salt lakes figured in the accompanying map (Fig. 129). And while the region of the Sahara was being elevated, that of the Mediterranean was probably being depressed.

These changes in the relation of sea to land, and the greater elevation of the mountains in the neighbouring countries, must have affected not merely the climate of southern, but also of north-western Europe, and ought not to be left out of account in any theory relating to pleistocene climate.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

fauna

|

|

| n.(一个地区或时代的)所有动物,动物区系 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

Mediterranean

|

|

| adj.地中海的;地中海沿岸的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

hippopotamus

|

|

| n.河马 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

glaciers

|

|

| 冰河,冰川( glacier的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

glacier

|

|

| n.冰川,冰河 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

atlas

|

|

| n.地图册,图表集 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

elevation

|

|

| n.高度;海拔;高地;上升;提高 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

affected

|

|

| adj.不自然的,假装的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

continental

|

|

| adj.大陆的,大陆性的,欧洲大陆的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

migration

|

|

| n.迁移,移居,(鸟类等的)迁徙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

drawn

|

|

| v.拖,拉,拔出;adj.憔悴的,紧张的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

herds

|

|

| 兽群( herd的名词复数 ); 牧群; 人群; 群众 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

antelopes

|

|

| 羚羊( antelope的名词复数 ); 羚羊皮革 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

antelope

|

|

| n.羚羊;羚羊皮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

varied

|

|

| adj.多样的,多变化的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

limestone

|

|

| n.石灰石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

descend

|

|

| vt./vi.传下来,下来,下降 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

minor

|

|

| adj.较小(少)的,较次要的;n.辅修学科;vi.辅修 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

marine

|

|

| adj.海的;海生的;航海的;海事的;n.水兵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

strata

|

|

| n.地层(复数);社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

ascertained

|

|

| v.弄清,确定,查明( ascertain的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

strictly

|

|

| adv.严厉地,严格地;严密地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

distinguished

|

|

| adj.卓越的,杰出的,著名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

testimony

|

|

| n.证词;见证,证明 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

geographical

|

|

| adj.地理的;地区(性)的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

cavern

|

|

| n.洞穴,大山洞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

caverns

|

|

| 大山洞,大洞穴( cavern的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

fortified

|

|

| adj. 加强的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

fissures

|

|

| n.狭长裂缝或裂隙( fissure的名词复数 );裂伤;分歧;分裂v.裂开( fissure的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

fissure

|

|

| n.裂缝;裂伤 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

perpendicular

|

|

| adj.垂直的,直立的;n.垂直线,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

implements

|

|

| n.工具( implement的名词复数 );家具;手段;[法律]履行(契约等)v.实现( implement的第三人称单数 );执行;贯彻;使生效 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

skulls

|

|

| 颅骨( skull的名词复数 ); 脑袋; 脑子; 脑瓜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

neolithic

|

|

| adj.新石器时代的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

grizzly

|

|

| adj.略为灰色的,呈灰色的;n.灰色大熊 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

rhinoceros

|

|

| n.犀牛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

roe

|

|

| n.鱼卵;獐鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

spotted

|

|

| adj.有斑点的,斑纹的,弄污了的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

rhinoceroses

|

|

| n.钱,钞票( rhino的名词复数 );犀牛(=rhinoceros);犀牛( rhinoceros的名词复数 );脸皮和犀牛皮一样厚 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

dens

|

|

| n.牙齿,齿状部分;兽窝( den的名词复数 );窝点;休息室;书斋 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

stratum

|

|

| n.地层,社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

gravel

|

|

| n.砂跞;砂砾层;结石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

purely

|

|

| adv.纯粹地,完全地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

reindeer

|

|

| n.驯鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

musk

|

|

| n.麝香, 能发出麝香的各种各样的植物,香猫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

porcupine

|

|

| n.豪猪, 箭猪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

ridge

|

|

| n.山脊;鼻梁;分水岭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

charcoal

|

|

| n.炭,木炭,生物炭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

flakes

|

|

| 小薄片( flake的名词复数 ); (尤指)碎片; 雪花; 古怪的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

attaining

|

|

| (通常经过努力)实现( attain的现在分词 ); 达到; 获得; 达到(某年龄、水平、状况) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

pal

|

|

| n.朋友,伙伴,同志;vi.结为友 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

trampling

|

|

| 踩( trample的现在分词 ); 践踏; 无视; 侵犯 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

descends

|

|

| v.下来( descend的第三人称单数 );下去;下降;下斜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

gunpowder

|

|

| n.火药 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

interred

|

|

| v.埋,葬( inter的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

grotto

|

|

| n.洞穴 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

baron

|

|

| n.男爵;(商业界等)巨头,大王 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

formerly

|

|

| adv.从前,以前 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

fully

|

|

| adv.完全地,全部地,彻底地;充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

lithograph

|

|

| n.平板印刷,平板画;v.用平版印刷 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

Oxford

|

|

| n.牛津(英国城市) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

megalopolis

|

|

| n.特大城市 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

derived

|

|

| vi.起源;由来;衍生;导出v.得到( derive的过去式和过去分词 );(从…中)得到获得;源于;(从…中)提取 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

vice

|

|

| n.坏事;恶习;[pl.]台钳,老虎钳;adj.副的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

corroborated

|

|

| v.证实,支持(某种说法、信仰、理论等)( corroborate的过去式 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

fathoms

|

|

| 英寻( fathom的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

eastwards

|

|

| adj.向东方(的),朝东(的);n.向东的方向 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

margin

|

|

| n.页边空白;差额;余地,余裕;边,边缘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

volcanic

|

|

| adj.火山的;象火山的;由火山引起的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

cedars

|

|

| 雪松,西洋杉( cedar的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

precipitated

|

|

| v.(突如其来地)使发生( precipitate的过去式和过去分词 );促成;猛然摔下;使沉淀 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

gorge

|

|

| n.咽喉,胃,暴食,山峡;v.塞饱,狼吞虎咽地吃 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

speck

|

|

| n.微粒,小污点,小斑点 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

shrubs

|

|

| 灌木( shrub的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

cape

|

|

| n.海角,岬;披肩,短披风 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

descended

|

|

| a.为...后裔的,出身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

perennial

|

|

| adj.终年的;长久的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

crest

|

|

| n.顶点;饰章;羽冠;vt.达到顶点;vi.形成浪尖 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

determined

|

|

| adj.坚定的;有决心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

watershed

|

|

| n.转折点,分水岭,分界线 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

tributaries

|

|

| n. 支流 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

gulf

|

|

| n.海湾;深渊,鸿沟;分歧,隔阂 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

extremity

|

|

| n.末端,尽头;尽力;终极;极度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

boulders

|

|

| n.卵石( boulder的名词复数 );巨砾;(受水或天气侵蚀而成的)巨石;漂砾 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

boulder

|

|

| n.巨砾;卵石,圆石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

uncommon

|

|

| adj.罕见的,非凡的,不平常的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

scooped

|

|

| v.抢先报道( scoop的过去式和过去分词 );(敏捷地)抱起;抢先获得;用铲[勺]等挖(洞等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

precipices

|

|

| n.悬崖,峭壁( precipice的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

eruptions

|

|

| n.喷发,爆发( eruption的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

crater

|

|

| n.火山口,弹坑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

granite

|

|

| adj.花岗岩,花岗石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

downwards

|

|

| adj./adv.向下的(地),下行的(地) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

striated

|

|

| adj.有纵线,条纹的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

backbone

|

|

| n.脊骨,脊柱,骨干;刚毅,骨气 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

ledges

|

|

| n.(墙壁,悬崖等)突出的狭长部分( ledge的名词复数 );(平窄的)壁架;横档;(尤指)窗台 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

colossal

|

|

| adj.异常的,庞大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

descending

|

|

| n. 下行 adj. 下降的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

alluvial

|

|

| adj.冲积的;淤积的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

detritus

|

|

| n.碎石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

jotted

|

|

| v.匆忙记下( jot的过去式和过去分词 );草草记下,匆匆记下 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

vertical

|

|

| adj.垂直的,顶点的,纵向的;n.垂直物,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

repose

|

|

| v.(使)休息;n.安息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

latitude

|

|

| n.纬度,行动或言论的自由(范围),(pl.)地区 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

geologists

|

|

| 地质学家,地质学者( geologist的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

upwards

|

|

| adv.向上,在更高处...以上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

thereby

|

|

| adv.因此,从而 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

necessitate

|

|

| v.使成为必要,需要 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

cones

|

|

| n.(人眼)圆锥细胞;圆锥体( cone的名词复数 );球果;圆锥形东西;(盛冰淇淋的)锥形蛋卷筒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

pointed

|

|

| adj.尖的,直截了当的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

silting

|

|

| n.淤积,淤塞,充填v.(河流等)为淤泥淤塞( silt的现在分词 );(使)淤塞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

sediment

|

|

| n.沉淀,沉渣,沉积(物) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

bluff

|

|

| v.虚张声势,用假象骗人;n.虚张声势,欺骗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

elevations

|

|

| (水平或数量)提高( elevation的名词复数 ); 高地; 海拔; 提升 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

abrupt

|

|

| adj.突然的,意外的;唐突的,鲁莽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

120

uneven

|

|

| adj.不平坦的,不规则的,不均匀的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

excavate

|

|

| vt.挖掘,挖出 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

depressed

|

|

| adj.沮丧的,抑郁的,不景气的,萧条的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

loam

|

|

| n.沃土 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |