The Caves of France, Baume, of Périgord.—Caves and Rock-shelters of Belgium, Trou de Naulette.—Caves of Switzerland.—Cave-dwellers3 and Pal4?olithic Men of River-deposits.—Classification of Pal?olithic Caves.—Relation of Cave-dwellers to Eskimos.—Pleistocene animals living north of Alps and Pyrenees.—Relation of Cave to River-bed Fauna.—The Atlantic Coastline.—Distribution of Pal?olithic Implements5.

The Caves of France.

The caves of France have been proved, by the explorations carried on during the course of the present century, to contain the same animals, introduced under the same conditions as those which we have already described. Some species, however, have been met with which have not been discovered in this country. In the cave of Lunel-viel, for example, the common striped hy?na of Africa (Hy?na striata) has been found by Marcel de Serres, to whom belongs the credit of being the first systematic7 explorer of caverns9 in France. In that of Bruniquel, the ibex, now found only in the higher mountains in Europe, the chamois and the Antelope10 saiga, an animal337 inhabiting the plains of the region of the Volga and of southern Siberia, have been identified by Prof. Owen; while in the collection obtained by Mr. Moggridge from the caves of Mentone, Prof. Busk has recognized the marmot. With these exceptions there is no distinction between the faunas11 of the bone-caves of this country and of France.219

The Cave of Baume.

The Machairodus latidens,220 or great sabre-toothed feline12 of Kent’s Hole, has been discovered in the cave of Baume in the Jura, according to M. Gervais,221 along with the horse, ox, wild-boar, elephant, a non-tichorhine species of rhinoceros13, the spotted14 hy?na, and the cave-bear, or the same group of animals as that with which it is found in Kent’s Hole. The cave is considered by M. Lartet222 to be of preglacial age.

The Caves of Périgord.

The caves and rock-shelters of Périgord, explored by the late M. Lartet and our countryman, Mr. Christy,338223 1863–4, have not only afforded cumulative16 proof of the co-existence of man with the extinct mammalia, but have given us a clue as to the race to which he belonged. They penetrate17 the sides of the valleys of the Dordogne and Vezère at various levels, as may be seen in Fig18. 71, and are full of the remains19 left behind by their ancient inhabitants, which give as vivid a picture of the human life of the period, as that revealed of Italian manners in the first century by the buried cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. The old floors of human occupation consist of broken bones of animals killed in the chase, mingled20 with rude implements, weapons of bone, and unpolished stone, and charcoal21 and burnt stones which point out the position of the hearths22.

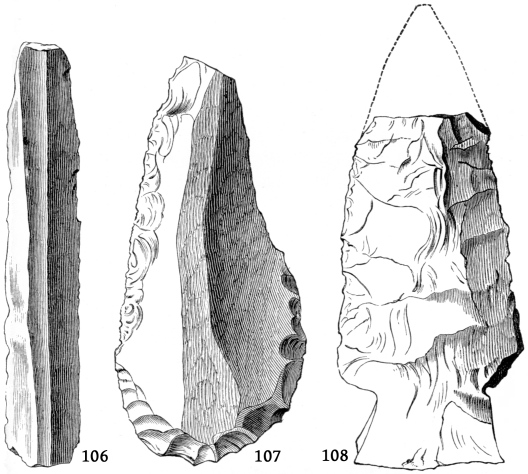

Flakes23 (Fig. 106) without number, rude stone-cutters, awls, lance-heads, hammers, saws made of flint or of chert, rest pêle-mêle with bone needles, sculptured reindeer25 antlers, engraved27 stones, arrow-heads, harpoons28, and pointed29 bones, and with the broken remains of the animals which had been used as food, the reindeer, bison, horse, the ibex, the saiga antelope, and the musk30 sheep. In some cases the whole is compacted by a calcareous cement into a hard mass, fragments of which are to be seen in the principal museums of Europe. This strange accumulation of débris marks, beyond all doubt, the place where ancient hunters had feasted, and the broken bones and implements are merely the refuse cast aside. The reindeer formed by far the larger portion of the food, and must have lived in enormous herds32 at that time in the centre of France. The severity of the climate at the time may be inferred by the presence of this animal, as well as by the accumulation of bones on the spots on which man had fixed33 his habitation. Indeed, had not this been the339 case, the decomposition34 of so much animal matter would have rendered the place uninhabitable even by the lowest savage35.

Fig. 106.—Flint-flake, Les Eyzies (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Fig. 107.—Flint Scraper, Les Eyzies (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Fig. 108.—Flint Javelin36-head, Laugerie Haute (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Besides the animals mentioned above, the cave-bear and lion have been met with in one, and the mammoth37 in five localities, and their remains bear marks of cutting or scraping, which show that they fell a prey38 to hunters. The Irish elk39, also, and the hy?na occur respectively in the cave of Laugerie Basse, and of Moustier, but the latter certainly did not gain access to the refuse-heaps, because the vertebr? are intact which it is in the habit of eating.340 For the same reason also, M. Lartet infers that the hunters were not aided in the chase by the dog. There is no evidence that they were possessed40 of any domestic animal. There were no spindle wheels to indicate a knowledge of spinning, nor potsherds to show an acquaintance with the potter’s art. In both these respects they resemble the Fuegians, Eskimos, and Australians, and contrast strongly with the neolithic42 races.

Fig. 109.—Flint Arrow-head, Laugerie Haute (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Fig. 110.—Bone needle, La Madelaine (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

The broken bones show that the reindeer furnished the more usual food, and next to that the horse, and then the bison. And from the absence of the vertebr? and pelvic bones of the two latter animals, M. Lartet concludes that they were cut up where they were killed, and the meat stripped from the backbone43 and the pelvis. Their food was probably cooked by boiling, the number of round stones used for heating water and bearing341 marks of fire, like the “pot boilers” of some of the American Indians, being very considerable.

Among the stone implements flint flakes were incredibly numerous, and the number of chips scattered44 about as well as the blocks of flint from which they had been struck, proved that they had been made on the spot; most of these flakes were notched45 by use (Fig. 106). Instruments with the ends carefully rounded off (Fig. 107) were also abundant, and from their analogy with similar instruments used by the Eskimos, there can be but little doubt that they were intended for the preparation of skins (compare Fig. 107 with Fig. 124). The ends of some were chipped to a point for insertion into a handle, while others rounded at both ends were probably used freely in the hand. In the cave of Moustier oval implements were met with, resembling those figured from the caverns of Kent’s Hole and Wookey (Figs47. 84 and 97). The spear, javelin, and arrow-heads of flint presented two modes of attachment48 to the shaft49, the base of some being squared off with a notch46 above for the ligature (as in Fig. 108), while in others (Fig. 109) it tapered50 off into a point intended for insertion. This latter form has been obtained also in Kent’s Hole.

The bone needles are carefully smoothed, and were pierced with a neatly-made eye (Fig. 110) by means of pointed flakes which were found along with them, and the use of which M. Lartet demonstrated by experiment. They had been sawn out of the compact metacarpals and tarsals of the reindeer224 and the horse, and subsequently rounded on fragments of sandstone, the grooves51 of which fitted them. In this, therefore,342 we have not merely the evidence that the hunters were in the habit of sewing, but also we have vividly52 brought before us the very method by which their needles were manufactured. They were probably used for sewing skins together, the tendon of a reindeer forming the thread, as among the modern Eskimos.

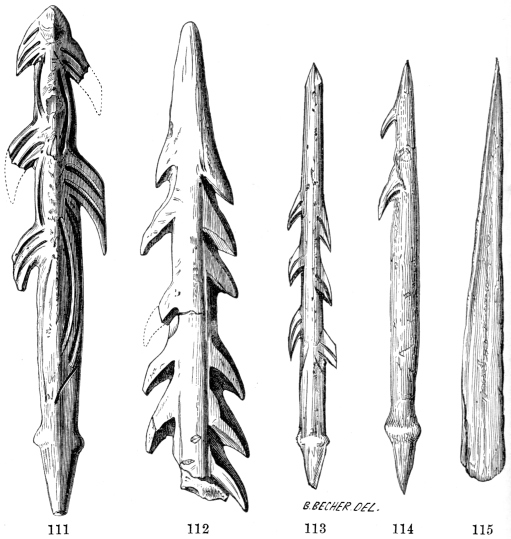

Figs. 111, 112.—Harpoons of Antler, La Madelaine. (Lartet and Christy.)

Figs. 113, 114.—Arrow-heads, Gorge53 d’Enfer. (Broca.)

Fig. 115.—Bone Awl24, Gorge d’Enfer (1/1). (Broca.)

The heads of arrows and lances are made principally out of reindeer antler, and are barbed, the barbs54 generally being grooved55, and carved on both sides of the axis343 (Figs. 111, 112, 113); but in some cases, as in Fig. 114, the barbs are only on one side. Many bones and antlers are variously carved into shapes for which it is impossible to assign a definite use. Fig. 115 is a bone awl.

Fig. 116.—Carved Handle of Reindeer Antler (1/2). (Lartet and Christy.)

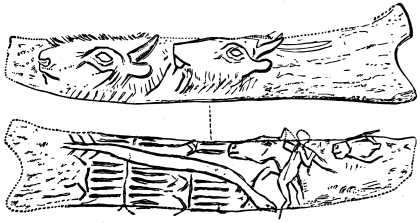

Fig. 117.—Two sides of Reindeer Antler, La Madelaine (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

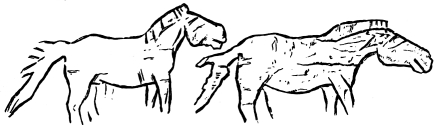

Fig. 118.—Horses engraved on Antler, La Madelaine (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

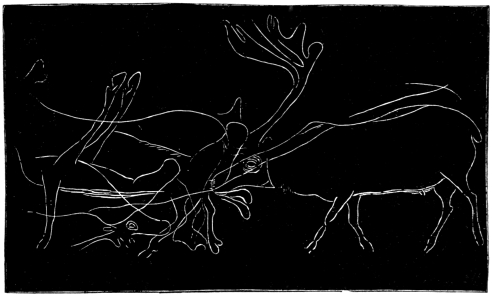

The most remarkable56 remains left behind by man in these refuse-heaps are the sculptured reindeer antlers, and the figures engraved on fragments of schist and on ivory. A well-defined outline of an ox stands out boldly from one piece of antler. A second presents us with a most elegant design: a reindeer is kneeling down in an easy attitude with its head thrown up in the air, so that the antlers rest on the shoulders, and the back of the animal forms an even surface for a handle, which is too small to be grasped in an ordinary European hand (Fig. 116). In a third a man stands close to a horse’s head, and hard by is a fish like an eel41; and on the other side of the same cylinder57 are two heads of bison, drawn58 with sufficient clearness to ensure recognition by anyone who had ever seen that animal (Fig. 117). On a fourth the natural curvature of one of the tines has been taken advantage of by the artist to engrave26 the head, and the characteristic recurved horns of the ibex; and on a fifth are figures of horses (Fig. 118), in which the upright disheveled mane and shaggy ungroomed tail are represented with admirable spirit. At first sight it would344 appear that the artist had drawn the heads out of all proportion to the bodies. A horse’s skeleton, however, from the pal?olithic “station” at Solutré, lately set up in the Museum at Lyons, proves that this is not the case, since, as M. Lortet pointed out to me, it is remarkable for its massive head, and small body. In Fig. 119 a group of reindeer are seen, two on their backs, and two in the act of walking. The Irish elk, red-deer, and probably rhinoceros, are also depicted59, the figures upon the hard schist being feebly and uncertainly drawn, as might be expected from the character of the tools. The most clever sculptor61 of modern times would, probably, not succeed very much better if his graver was a splinter of flint, and stone and bone were the materials to be engraved. One peculiarity63 runs through the figures of animals. With but two exceptions none345 of the feet are represented, a circumstance which is probably due, as Mr. Franks has suggested to me, to the fact that the hunters merely represented what they saw of the animal, of which the feet would be concealed64 by the herbage.

Fig. 119.—Group of Reindeer, Dordogne. (Broca.)

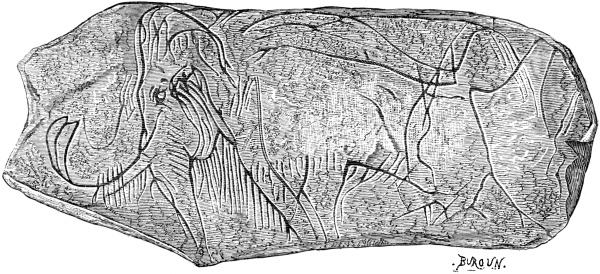

The most striking figure that has been discovered is that of the mammoth,225 Fig. 120, engraved on a fragment of its own tusk65, the peculiar62 spiral curvature of the tusk and the long mane, which are not now to be found in any living elephant, proving that the original was familiar to the eye of the artist. The discovery of whole carcases of the animal in northern Siberia, preserved from decay in the frozen cliffs and morasses66, has made us acquainted with the existence of the long hairy mane. Had not it thus been handed down to our eyes, we should probably have treated this most accurate drawing as a mere31 artist’s freak. Its peculiarities67 are so faithfully depicted that it is quite impossible346 for the animal to be confounded with either of the two living species. These drawings probably employed347 the idle hours of the hunter, and perpetuate68 the scenes which he witnessed in the chase. They are full of artistic69 feeling, and are evidently drawn from life. The mammoth is engraved on its own ivory, the reindeer generally on reindeer antler, and the stag on stag antler.

Fig. 120.—Mammoth engraved on Ivory, La Madelaine (1/2). (Lartet and Christy.)

From all these facts we must picture to our minds, that these ancient dwellers in the caves of Aquitaine lived by hunting and fishing, that they were acquainted with fire, and that they were clad with skins sewn together with sinews or strips of intestines70. That they did not possess the dog is shown, not merely by the negative evidence of its not having been discovered, but also by the fact that the bones which it invariably eats, such as the vertebr?, are preserved. They did not possess any domestic animals, and there is no evidence that they were acquainted with the potter’s art. M. de Mortillet’s view, that the art of making pottery71 was unknown in the pal?olithic age, seems to me to be probably true, the reputed cases of the discovery of potsherds being always connected with suspicious circumstances, which render it probable that they were subsequently introduced.

Besides the remains of the animals in the refuse-heaps were fragmentary portions of human skeletons, which, however, were not scraped or broken so as to imply the practice of cannibalism72.

Caves of Belgium.

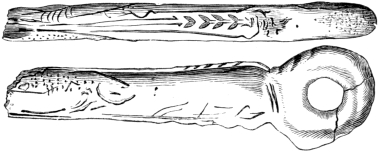

Fig. 121.—Carved Implement6 of Reindeer Antler, Goyet (1/2). (Dupont.)

The researches of Dr. Schmerling226 into the caves of Belgium, in 1829–30, revealed the fact that the animals348 so abundant in the caves of Germany, were equally numerous in those in the neighbourhood of Liége, and the flint flakes, and the fragments of human bones, which he found may possibly be of pal?olithic age. He also discovered the remains of the porcupine73, a species no longer living north of the Alps and Pyrenees. The systematic exploration, however, of the pal?olithic caves in that district was not carried out until, in the year 1864, M. Dupont227 began the investigation74 of those in the neighbourhood of Dinant-sur-Meuse, on behalf of the Belgian Government. His results, based upon the examination of upwards75 of twenty caves and rock-shelters, are published in a series of papers read before the Royal Academy of Belgium and subsequently in a separate work. Besides the remains of the animals living in Belgium within the historic period, he met with the ibex, chamois, and marmot, which are now to be found only in the mountainous districts of Europe, the tailless hare, lemming, and arctic fox, of the northern regions, the Antelope saiga, grizzly76 bear, lion, hy?na, and others. Most of these species occurred in refuse accumulations, their remains being in the fragmentary condition of those of the French caves. The349 associated implements are of the same type as those of Périgord, and some of them are ornamented77 in the same manner as, for example, that from the cavern8 of Goyet, Fig. 121, termed a “baton de commandement,” but which, from its analogy with similar articles in the British Museum, is most probably an arrow-straightener. Those of flint are also of the same kind, and in several of the caves there was the same association of fragmentary human remains with the relics78 of the feasts as in the French refuse-heaps.

Trou de Naulette.

The human remains consisting of a lower jaw79, ulna and metatarsal, discovered in the large cavern of Naulette,228 on the left bank of the Lesse, in association with the broken remains of the rhinoceros, mammoth, reindeer, chamois, and marmot, are undoubtedly80 of pal?olithic age, since they rested in an undisturbed stratum81. M. Dupont gives the following section in descending82 order.

METRES.

1. Sandy grey and yellow clay 2·90

2. Yellow grey clay with stones and bones of ruminants 0·45

3. Stalagmite.

4. Tufa.

5. Three bands of clay alternating with stalagmite.

6. Sandy clay with human bones at the depth of four metres.

7. Stalagmite.

8. Cave-earth with bones gnawed83 by hy?nas.

The human jaw is remarkable for its prognathism, which, according to Dr. Hamy, is greater than that which350 has been observed in any living races. The cave had afforded shelter to the hy?nas before it had been used by man.

The Caves of Switzerland.

The caves of Switzerland also contain the same class of rude implements and carvings84. Prof. Rupert Jones has called my attention to a recent discovery of carved reindeer antlers, and harpoon-heads, similar to those figured from the Dordogne, in a cave in the Canton of Schaaffhausen,229 along with the bones of hy?na, reindeer, and mammoth. In that of Veyrier,230 carved implements were found along with the remains of the ox, horse, chamois, and ibex, some of which, shown to me by Dr. Gosse, at the meeting of the French Association for the Advancement85 of Science, at Lyons in 1873, are of the same form and size as the arrow-straightener from the cave of Goyet (Fig. 121).

We may, therefore, infer that the same pal?olithic race of men once ranged over the whole region from the Pyrenees and Switzerland, as far to the north as Belgium. And since Prof. Fraas has obtained similar implements from a refuse-heap at Schussenreid in Würtemberg, they wandered as far to the east as that district, while the discoveries in Kent’s Hole and Wookey Hole prove that they extended as far to the west as Somersetshire and Devonshire.

351

Cave-dwellers and Pal?olithic Men of the River-gravels86.

These pal?olithic cave-dwellers are considered by Mr. Evans231 to belong to the same race as those who have left their rude flint implements in the river-gravels in the valleys of the Thames, the Somme, the Seine, and in the eastern counties, as far to the north as Peterborough. We must, however, allow that a marked difference is to be observed between a series of flint implements found in the caves, as compared with a series found in the river-strata, although some forms are common to the two; as for instance some of those found in Brixham and Kent’s Hole. This difference can scarcely be explained on the supposition that the small things would be less likely to be preserved in the fluviatile deposits, because it leaves the rarity in the caves of the larger fluviatile forms unaccounted for. It is perhaps safer, in the present state of our knowledge, to consider the two sets to be distinct from each other. The direct superposition in Kent’s Hole of the stratum with the ordinary cave-type of implement, over that with the ordinary fluviatile type, may perhaps prove that the latter is the older.

Classification of Pal?olithic Caves.

The pal?olithic caves are divided by M. Lartet232 into four groups, according to the species of animals which they contain; into those of the age of the cave-bear, of the age of the mammoth and woolly rhinoceros, of the352 age of the reindeer, and of the age of bison. Dr. Hamy follows Sir John Lubbock,233 in considering the age of the cave-bear to be co-extensive with that of the mammoth, and in the classification of caves he adopts a series of transitions. M. Dupont divides the caves of Belgium into those belonging to the age of the mammoth, and to that of the reindeer.

It is easy to refer a given cave to the age of the reindeer or of the mammoth because it contains the remains of those animals, but the division has been rendered worthless for chronological88 purposes, by the fact that both these animals inhabited the region north of the Alps and Pyrenees at the same time, and are to be found together in nearly every bone-cave explored in that area. The difference between the contents of one pal?olithic cave and another, is probably largely due to the fact that man could more easily catch some animals than others, as well as to the preference for one kind of food before another. And the abundance of the reindeer, which is supposed to characterise the reindeer period, may reasonably be accounted for by the fact, that it would be more easily captured by a savage hunter, than the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, cave-bear, lion, or hy?na. The classification will apply, as I have shown in my essay on the pleistocene mammalia,234 neither to the caves of this country, of Belgium, nor of France, and my views are shared by M. de Mortillet,235 after a careful and independent examination of the whole evidence.

The division of the caves also into ages, according to353 the various types of implements found in them, proposed by M. de Mortillet, seems to be equally unsatisfactory; for there is no greater difference in the implements of any two of the pal?olithic caves, than is to be observed between those of two different tribes of Eskimos, while the general resemblance is most striking. The principle of classification by the relative rudeness, assumes that the progress of man has been gradual, and that the ruder implements are therefore the older. The difference, however, may have been due to different tribes, or families, having co-existed without intercourse89 with each other, as is now generally the case with savage communities; or to the supply of flint, chert, and other materials for cutting instruments, being greater in one region than in another.

Relation of Cave-dwellers to Eskimos.

Fig. 122.—Eskimos Spear-head, bone (1/2).

Fig. 123.—Eskimos Arrow-straightener of Walrus90 Tooth (1/1). (Brit. Mus.)

Can these cave-dwellers be identified with any people now living on the face of the earth? or are they as completely without representatives as their extinct contemporaries, the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros? Absolute certainty we cannot hope to obtain on the point, but the cumulative evidence enables an answer to be given which is probably true. Along the American shore of the great Arctic Ocean, in the region of everlasting91 snow, dwell the Eskimos, living by hunting and354 fishing, speaking the same language, and using the same implements from the Straits of Behring on the west, to Greenland on the east. Their implements and weapons, brought home by the arctic explorers, enable us to institute a comparison with those found in the pal?olithic caves. The harpoons in the Ashmolean collection at Oxford92, brought over by Captain Beechey and Lieut. Harding from West Georgia, as well as those in the British Museum, are almost identical in shape and design with those from the caves of Aquitaine and Kent’s Hole; the only difference being that some of the latter have grooved barbs. The heads of the fowling93 and fishing spears, darts94, and arrows, as well as the form of their bases for insertion into the shafts95, are also identical (Fig. 122), as may be seen from a comparison of Fig. 122 with Figs. 99 and 114. The355 curiously96 carved instrument, Fig. 123, which the Eskimos use for straightening their arrows is variously ornamented with designs of animals, analogous97 to those cut on the reindeer antlers in Aquitaine; and if it be compared with the so-called “baton de commandement,” Fig. 121, it will be seen, that the latter also was probably intended for the same purpose; the difference in the shape of the hole in the two figured specimens98 being also observable in the series of Eskimos arrow-straighteners in the British Museum, and being largely due to friction99 by use. Many of the implements are the same in form. An Eskimos stone scraper for preparing skins, or plane for smoothing wood, is represented in Fig. 124, which is inserted in a handle of fossil mammoth ivory, obtained from the frozen ice-cliffs on the shores of the Arctic sea. If it be compared with Fig. 107 from the caves, it will be seen to be of the same pattern. It is indeed not a little singular, that the handle in which it is imbedded should have been formed out of the tusks100 of the same species of elephant as that which was depicted by the pal?olithic hunter (see Fig. 120), in the south of France.

Fig. 124.—Eskimos Plane or Scraper (1/1). (Lartet and Christy.)

Some of the Eskimos lance-heads of stone in the British Museum are of the same type as that figured from the caves of the Dordogne (Fig. 108).

356 The most remarkable objects brought home from the northern regions are the implements of bone and antler which are ornamented with the figures of animals hunted by the Eskimos on sea or land. On the side of one bow in the Ashmolean Museum, used for drilling holes, you see them harpooning101 the whale from their skin boats, and catching102 birds. On a second they are harpooning walrus and catching seals; on a third the seals are being dragged home. The huts in which they live, the tethered dogs, the boat supported on its platform, and their daily occupations are faithfully represented. One bow is ornamented with a large number of porpoises103, while on another is a reindeer hunt in which the animals are being attacked while they are crossing a ford15. On a bone implement in the British Museum from Fort Clarence, the reindeer are being shot down by archers104 (Fig. 125). The arrow straightener, Fig. 123, is adorned105 with a reindeer hunting scene, in which the animals are seen browsing106 and unsuspicious of the approach of the hunters, who are advancing, clad in reindeer skins and wearing antlers on their heads.

A comparison of these various designs with those from the caves of France and Belgium shows an identity of plan and workmanship, with this difference only, that the hunting scenes familiar to the pal?olithic cave-dweller were not the same as those familiar to the Eskimos on the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Each sculptured the animals he knew, and the whale, walrus, and seal were unknown to the inland dwellers in Aquitaine, just as the mammoth, bison, and wild horse are unknown to the Eskimos. The reindeer, which they both knew, is represented in the same way by both. The West Georgians made their dirks of walrus tooth, and ornamented357 them with carvings of the backbones107 of fishes; the people of Aquitaine used for the same purpose reindeer antlers, and ornamented them with figures of that animal (see Fig. 116). And it is worthy108 of remark that the latter had sufficient artistic feeling to depict60 the mammoth on mammoth ivory, the reindeer generally on reindeer antler, and the stag on its own antler.

Fig. 125.—Eskimos Hunting-scene (1/1). (Fort Clarence.)

An appeal to the habits of these two peoples, now separated by so wide an interval109 of space and time, tends also to show that they are descended110 from the same stock. The method of accumulating large quantities of the bones of animals around their dwelling-places, and the habit of splitting the bones for the sake of the marrow111, is the same in both. Their hides were prepared by the same sort of instruments and in the same manner, and the needles with which they were sewn together are of the same pattern. The few remains of man among the relics of feasts in the caves of Belgium and France, show the same disregard of sepulture as that implied by the human skulls113 lying about along with numerous bones of walrus, seal, dog, bear, and fox, in an Eskimos camp in Igloolik, which were carried away by Captain Lyon, without the slightest objection on the part of the relatives of the dead.

All these facts can hardly be mere coincidences, caused by both peoples leading a savage life under similar circumstances: they afford reasons for the belief that358 the Eskimos of North America are connected by blood with the pal?olithic cave-dwellers of Europe. To the objection that savage tribes living under similar conditions use similar instruments, and that, therefore, the correspondence of those of the Eskimos with those of the reindeer folk does not prove that they belong to the same race, the answer may be made, that there are no two savage tribes now living which use the same set of implements, without being connected by blood. The agreement of one or two of the more common and ruder instruments may be perhaps of no value in classification, but if a whole set agree, fitted for various uses, and some of them rising above the most common wants of savage life, we must admit that the argument as to race is of very great value. The implements found in Belgium, France, or Britain differ scarcely more from those now used in West Georgia, than the latter do from those now in use in Greenland or Melville Peninsula. The conclusion, therefore, seems inevitable114, that so far as we have any evidence of the race to which the dwellers in the Dordogne belong, that evidence points only in the direction of the Eskimos.

This conclusion is to a great extent confirmed by a consideration of the animals found in the caves. The reindeer and the musk sheep afford food to the Eskimos now, just as they afforded it to the pal?olithic hunters in Europe. No naturalist115 would deny that the pleistocene musk sheep is of the same species as that of North America, and although the animal is extinct in Europe and Asia, its remains, scattered through Germany, Russia in Europe, and Siberia, show that it formerly116 ranged in the whole of that area. The enormous distance, therefore, of southern France from the northern shores of America,359 cannot be considered as an obstacle to this view, for, to say the least, pal?olithic man would have had the same chance of retreating to the north-east as the musk sheep. The mammoth and bison have also been tracked by their remains in the frozen river gravels and morasses through Siberia, as far to the north-east as the American side of the Straits of Behring. Pal?olithic man appeared in Europe with the arctic mammalia, lived in Europe along with them, and disappeared with them. And since his implements are of the same kind as those of the Eskimos, it may reasonably be concluded that he is represented at the present time by the Eskimos, for it is most improbable that the convergence of the ethnological, and zoological evidence should be an accident. These views,236 which I advanced in 1866, have been to a great extent accepted by Sir John Lubbock in his last edition of Prehistoric117 Man.

Pleistocene Animals living to the North of the Alps and Pyrenees.

The principal mammalia inhabiting Britain, France, and Germany during the pleistocene age, and contemporary with man in Europe, are given in the following table, which shows that the fauna of the region to the north of the Alps and Pyrenees was remarkably118 uniform. The cave-fauna of Provence, Italy, and Spain, will be treated of in the next chapter.

360

(Image of Table)

Species. Gailenreuth Cave Kirkdale Victoria Cefn Plas-

newydd Plas Heaton Gallfaenan Paviland Bacon’s Hole Minchin Hole Bosco’s Den1 Crow Hole Ravenscliff Spritsail Tor Long Hole Blackrock Fissure119 Caldy Fissure Coygan Cave Hoyle Cave King Arthur’s Cave

Homo pal?olithicus—Pal?olithic Man x x x x x x

Spermophilus citillus—Pouched Marmot

Arctomys marmotta—Common Marmot

Castor fiber—Beaver

Lepus timidus—Hare x x x

Lepus variabilis—Alpine Hare

Lepus cuniculus—Rabbit x x x

Lepus diluvianus—Extinct Hare

Lagomys pusillus—Tailless Hare

Mus lemmus—Lemming

Hystrix dorsata—Porcupine x

Felis leo (var. spel?a)—Lion x x x x x x

Felis pardus—Leopard

Felis Lynx—Lynx

Felis caffer—Caffir Cat

Felis catus—Wild Cat x x x

Machairodus latidens

Gulo borealis—Glutton x x

Hy?na crocuta (var. spel?a)—Spotted Hy?na x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Hy?na striata—Striped Hy?na

Mustela martes—Marten x x x

Mustela putorius—Polecat x x x

Mustela erminea—Weasel x x

Lutra vulgaris—Otter x

Ursus arctos—Brown Bear x x x ? x x

Ursus ferox—Grizzly Bear x x x x x x x x

Ursus spel?us—Cave-Bear x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Canis lupus—Wolf x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Canis vulpes—Fox x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Canis lagopus—Arctic Fox

Elephas primigenius—Mammoth x x x x x x x x x x

Elephas antiquus x x x x x x x x x

Elephas Africanus—African Elephant

Equus caballus—Horse x x x x x x x x x x x x

Rhinoceros tichorhinus—Woolly Rhinoceros x x x x x x x x

Rhinoceros hemit?chus x x x x x x x x

Rhinoceros megarhinus

Bos urus—Urus

Bos bison—Bison x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Ovibos moschatus—Musk Sheep

Capra ibex—Ibex

Capella rupicapra—Chamois

Antilope saiga—Saiga

Sus scrofa—Wild Boar x x x x x x x x x x x

Cervus elaphus—Stag x x x x x x x x x

Cervus capreolus—Roe x x x x

Cervus megaceros—Irish Elk x x x x x x x x

Cervus tarandus-Reindeer x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Hippopotamus120 amphibius (var. major)— Hippopotamus x x x x

361

(Image of Table)

Species. Durdham Hutton Banwell Bleadon Uphill Sandford Hill Wookey Hole Brixham Kent’s Hole Moustier La Madelaine Laugerie Haute Laugerie Basse Gorge d’Enfer Cro Magnon Les Eyzies Lunel Viel Belgian Caves River Deposits, Britain River Deposits, France

Homo pal?olithicus—Pal?olithic Man x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Spermophilus citillus—Pouched Marmot x x x x x x

Arctomys marmotta—Common Marmot x

Castor fiber—Beaver x x x x x

Lepus timidus—Hare x x x x x x? x? x x x x x

Lepus variabilis—Alpine Hare x

Lepus cuniculus—Rabbit x x x x x

Lepus diluvianus—Extinct Hare x x x x

Lagomys pusillus-Tailless Hare x x x x

Mus lemmus—Lemming x x x x x

Hystrix dorsata—Porcupine x

Felis leo (var. spel?a)—Lion x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Felis pardus—Leopard x x x x x

Felis Lynx—Lynx x x x

Felis caffer—Caffir Cat x x

Felis catus—Wild Cat x ? x x x x x

Machairodus latidens x

Gulo borealis—Glutton x x x

Hy?na crocuta (var. spel?a)—Spotted Hy?na x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Hy?na striata—Striped Hy?na x

Mustela martes—Marten x x

Mustela putorius—Polecat x

Mustela erminea—Weasel x x x

Lutra vulgaris—Otter x x x x x

Ursus arctos—Brown Bear x x x x x x x x x

Ursus ferox—Grizzly Bear x x x x x x x

Ursus spel?us—Cave-Bear x x x x x x x x x x x x (?)

Canis lupus—Wolf x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Canis vulpes—Fox x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Canis lagopus—Arctic Fox x

Elephas primigenius—Mammoth x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Elephas antiquus x x x x x

Elephas Africanus—African Elephant

Equus caballus—Horse x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Rhinoceros tichorhinus—Woolly Rhinoceros x x x x x x x x

Rhinoceros hemit?chus x x x x

Rhinoceros megarhinus x x

Bos urus—Urus x x x x x x x x x x

Bos bison—Bison x x x x x x ? x x x x x x x x x x

Ovibos moschatus—Musk Sheep x x x x

Capra ibex—Ibex x x x x x x x x

Capella rupicapra—Chamois x x x x x

Antilope saiga—Saiga x x x

Sus scrofa—Wild Boar x x x x x x x x x x x

Cervus elaphus—Stag x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x

Cervus capreolus—Roe x x x x x

Cervus megaceros—Irish Elk x x x x x x x x x

Cervus tarandus—Reindeer x x x x x x x x x x + x + x x x x x

Hippopotamus amphibius (var. major)—Hippopotamus x (?) x x

362

Cave Fauna the same as River-bed Fauna.

If this list237 of animals from the caves be compared with that of the river-deposits of Britain and the continent, it will be seen that the same fauna is present in both, and that they are therefore of the same geological age.238 This was the conclusion to which Dr. Falconer was led by the examination of the caves of Gower, and it has been confirmed by every subsequent discovery.

The Pleistocene Coast-line of North-Western Europe.

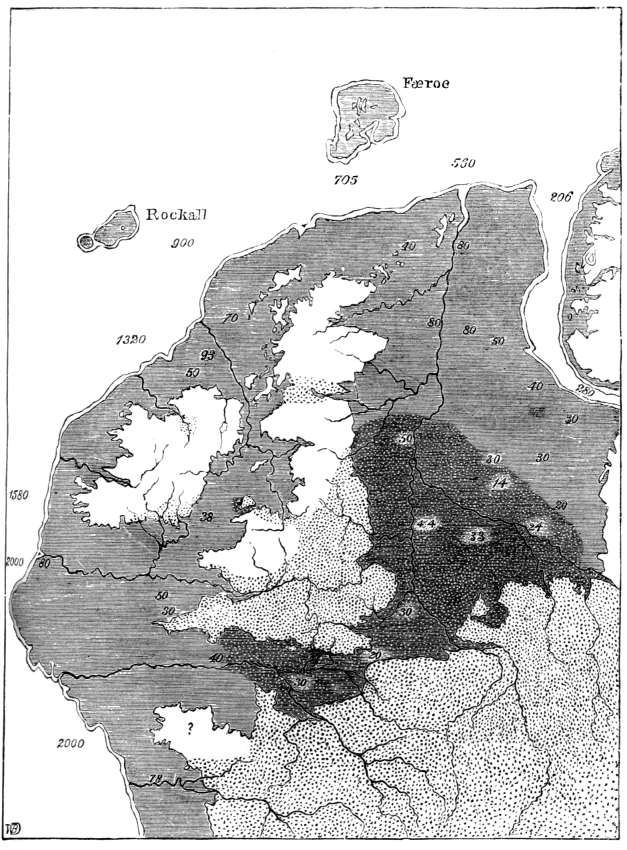

The identity of the British pleistocene fauna with that of the continent, leads to the conclusion that in the pleistocene age Britain was connected with the adjacent countries by a bridge of land, over which the wild animals had free means of migration121. And this might be brought about by a comparatively small elevation122 of the area. The soundings show that Britain and Ireland constitute merely the uplands of a plateau now submerged to the extent of about 100 fathoms123, on the side of the Atlantic. On the east it extends at a depth of from twenty to fifty fathoms, in the direction of Belgium; and on the south it is only sunk from twenty to forty fathoms below the sea-level. Immediately to the westward124 of this line the sea deepens so suddenly, that there is scarcely any difference between the lines of 100 and of 200363 fathoms, and the depth rapidly increases to 2,000. Were this plateau elevated above the sea to an extent of 100364 fathoms, the tract125 shaded in the map (Fig. 126) would unite the British Isles127 to the continent, and the Thames and other rivers on the eastern coast would unite with the Elbe and the Rhine to form a river debouching on the North Sea, somewhat after the manner which I have represented by taking the deepest line of soundings. The Straits of Dover would then be the watershed129 between this valley of the German Ocean, as it may be termed, and that of the English Channel, in which the Seine and the Somme and other French rivers joined those of the south coast, and ultimately reached the Atlantic. Evidence that the latter river flowed in the course assigned to it in the map is afforded by the discovery of the fresh-water mussel (Unio pictorum), recorded by Mr. Godwin Austen239 to have been dredged up by Captain White from a depth of from 50 to 100 fathoms, not very far from what I have taken to be its mouth. We are also indebted to Mr. Godwin Austen for the discovery near this spot of banks of shingle130 and littoral131 shells, which indicate the position of the ancient coast-line.

Fig. 126.—Physiography of Great Britain in Late Pleistocene Age.

Shaded area = land now submerged; dotted area = region occupied by animals;

plain area = region occupied by glaciers132.

The view that the 100-fathom line marks the limit of the pleistocene land surface to the west, is held by Sir H. de la Bêche, Mr. Godwin Austen, Sir Charles Lyell, and other eminent133 geologists134, and it is supported by many facts that can be explained in no other manner. To pass over the discovery of a fresh-water shell at the bottom of the English Channel, quoted above, the distribution of fossil mammalia at the bottom of the German Ocean (represented in Fig. 126 by the dotted area) is365 analogous to that which we find in the river gravels and brick-earths on the land. The quantity of teeth and bones belonging to the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, horse, reindeer, and spotted hy?na, and other animals, dredged up by the fishermen in the German Ocean is almost incredible. Mr. Owles, of Yarmouth, informed me in 1868 that off that place there is a bank on which the fishing nets are rarely cast without bringing up fossil remains. It seems most probable, that these accumulations have been formed under subaerial conditions near the drinking places, or below the fords, which were used for ages by the pleistocene animals. I might quote as an example of a similar deposit of fossils on the land, that discovered in 1866 by Captain Luard, R.E., in digging the foundations of the new cavalry135 barracks at Windsor, which consisted mainly of bones and antlers of reindeer, with a few carnivores, such as the brown bear and wolf, that usually follow reindeer in their migrations136 in Siberia.240 Were this submerged it would be a case precisely137 similar to that off Yarmouth.

The ancient forest, exposed at low water under the cliffs on the Norfolk and Suffolk shores, flourished when the land stood higher than it does now. Traces of a similar forest, also at, and below, low-water mark, have been met with on the shore at Selsea, near Chichester, in Sussex; and remains of the mammoth have been dredged up in several places off the coast, as for example in Torbay and in Holyhead harbour, or found in gravel87 beds near low-water mark, as in the Isle126 of Wight, and on the north coast of Somerset at St. Audries, near Watchet, where a skull112 with gigantic tusks rested in the366 gravel. In all these facts we have ample proof that Britain stood at a higher level in the pleistocene age than at the present day.

The vast abundance also of the mammalia in the caves of South Wales and Somerset, and their presence in the Island of Caldy, and it may be added in Ireland, can only be accounted for by the elevation of the present sea-bottom, so as to allow of their migration over plains covered with abundant pasture. It seems, therefore, to me that the accompanying map, Fig. 126, represents with tolerable accuracy the ancient coast-line of Britain, and of the adjacent parts of the continent in the pleistocene age. The fertile valleys of the English Channel, Bristol Channel, and the German Ocean, would afford sustenance138 to a large and varied139 fauna, and numerous herbivores, such as the reindeer, bison, and horse, would supply food to the pal?olithic hunters, who followed them in their annual migrations. And it must be remarked on this hypothesis, that the valley of the Garonne would offer a free passage both to the animals and to the hunters of Auvergne down to the prairie, extending as far as the 100-fathom line off the French coast, and that the hunting grounds would reach to Devonshire and Somerset without any barrier except that offered by the rivers. It is therefore no wonder that the implements in the caves of Kent’s Hole, Wookey Hole, and the South of France, should be of the same type.

Distribution of Pal?olithic Implements in this Area.

This geographical140 configuration141 in pleistocene times may perhaps account for the distribution of the pal?olithic implements in the river gravels. The Seine and367 the Somme debouch128 into the same valley as the rivers of the south of England, and the Straits of Dover mark the position of a low watershed leading into the valley of the German Ocean, on the sides of which, in the eastern counties, river-bed implements are so numerous. These are of the same type in northern France, Sussex, Hampshire, Kent, and as far north as the Wash; and were therefore used by the same race of men. The difference between them and those of the cave-dwellers in the south and west, may be due to their possessors occupying different hunting grounds. Each tribe of American Indians at the present time has its own territory for hunting, which is jealously guarded against encroachment142, and in which the articles peculiar to the tribe are being accumulated in the refuse-heaps, while other sets are being accumulated in other districts. If we suppose that the pal?olithic savages143 divided up their hunting grounds in this manner, the difference which exists between the implements of the river-beds and caves may be readily explained, as well as their being found for the most part in different areas.

The pleistocene climate in the area north of the Alps and Pyrenees will be treated in the eleventh chapter, after the examination of the cave-fauna of southern Europe.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

den

|

|

| n.兽穴;秘密地方;安静的小房间,私室 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

fauna

|

|

| n.(一个地区或时代的)所有动物,动物区系 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

dwellers

|

|

| n.居民,居住者( dweller的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

pal

|

|

| n.朋友,伙伴,同志;vi.结为友 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

implements

|

|

| n.工具( implement的名词复数 );家具;手段;[法律]履行(契约等)v.实现( implement的第三人称单数 );执行;贯彻;使生效 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

implement

|

|

| n.(pl.)工具,器具;vt.实行,实施,执行 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

systematic

|

|

| adj.有系统的,有计划的,有方法的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

cavern

|

|

| n.洞穴,大山洞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

caverns

|

|

| 大山洞,大洞穴( cavern的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

antelope

|

|

| n.羚羊;羚羊皮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

faunas

|

|

| 动物群 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

feline

|

|

| adj.猫科的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

rhinoceros

|

|

| n.犀牛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

spotted

|

|

| adj.有斑点的,斑纹的,弄污了的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

Ford

|

|

| n.浅滩,水浅可涉处;v.涉水,涉过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

cumulative

|

|

| adj.累积的,渐增的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

penetrate

|

|

| v.透(渗)入;刺入,刺穿;洞察,了解 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

mingled

|

|

| 混合,混入( mingle的过去式和过去分词 ); 混进,与…交往[联系] | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

charcoal

|

|

| n.炭,木炭,生物炭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

hearths

|

|

| 壁炉前的地板,炉床,壁炉边( hearth的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

flakes

|

|

| 小薄片( flake的名词复数 ); (尤指)碎片; 雪花; 古怪的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

awl

|

|

| n.尖钻 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

reindeer

|

|

| n.驯鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

engrave

|

|

| vt.(在...上)雕刻,使铭记,使牢记 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

engraved

|

|

| v.在(硬物)上雕刻(字,画等)( engrave的过去式和过去分词 );将某事物深深印在(记忆或头脑中) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

harpoons

|

|

| n.鱼镖,鱼叉( harpoon的名词复数 )v.鱼镖,鱼叉( harpoon的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

pointed

|

|

| adj.尖的,直截了当的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

musk

|

|

| n.麝香, 能发出麝香的各种各样的植物,香猫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

mere

|

|

| adj.纯粹的;仅仅,只不过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

herds

|

|

| 兽群( herd的名词复数 ); 牧群; 人群; 群众 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

fixed

|

|

| adj.固定的,不变的,准备好的;(计算机)固定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

decomposition

|

|

| n. 分解, 腐烂, 崩溃 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

savage

|

|

| adj.野蛮的;凶恶的,残暴的;n.未开化的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

javelin

|

|

| n.标枪,投枪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

mammoth

|

|

| n.长毛象;adj.长毛象似的,巨大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

prey

|

|

| n.被掠食者,牺牲者,掠食;v.捕食,掠夺,折磨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

elk

|

|

| n.麋鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

possessed

|

|

| adj.疯狂的;拥有的,占有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

eel

|

|

| n.鳗鲡 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

neolithic

|

|

| adj.新石器时代的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

backbone

|

|

| n.脊骨,脊柱,骨干;刚毅,骨气 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

scattered

|

|

| adj.分散的,稀疏的;散步的;疏疏落落的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

notched

|

|

| a.有凹口的,有缺口的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

notch

|

|

| n.(V字形)槽口,缺口,等级 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

figs

|

|

| figures 数字,图形,外形 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

attachment

|

|

| n.附属物,附件;依恋;依附 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

shaft

|

|

| n.(工具的)柄,杆状物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

tapered

|

|

| adj. 锥形的,尖削的,楔形的,渐缩的,斜的 动词taper的过去式和过去分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

grooves

|

|

| n.沟( groove的名词复数 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏v.沟( groove的第三人称单数 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

vividly

|

|

| adv.清楚地,鲜明地,生动地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

gorge

|

|

| n.咽喉,胃,暴食,山峡;v.塞饱,狼吞虎咽地吃 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

barbs

|

|

| n.(箭头、鱼钩等的)倒钩( barb的名词复数 );带刺的话;毕露的锋芒;钩状毛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

grooved

|

|

| v.沟( groove的过去式和过去分词 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

cylinder

|

|

| n.圆筒,柱(面),汽缸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

drawn

|

|

| v.拖,拉,拔出;adj.憔悴的,紧张的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

depicted

|

|

| 描绘,描画( depict的过去式和过去分词 ); 描述 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

depict

|

|

| vt.描画,描绘;描写,描述 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

sculptor

|

|

| n.雕刻家,雕刻家 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

peculiarity

|

|

| n.独特性,特色;特殊的东西;怪癖 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

concealed

|

|

| a.隐藏的,隐蔽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

tusk

|

|

| n.獠牙,长牙,象牙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

morasses

|

|

| n.缠作一团( morass的名词复数 );困境;沼泽;陷阱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

67

peculiarities

|

|

| n. 特质, 特性, 怪癖, 古怪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

perpetuate

|

|

| v.使永存,使永记不忘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

artistic

|

|

| adj.艺术(家)的,美术(家)的;善于艺术创作的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

intestines

|

|

| n.肠( intestine的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

pottery

|

|

| n.陶器,陶器场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

cannibalism

|

|

| n.同类相食;吃人肉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

porcupine

|

|

| n.豪猪, 箭猪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

investigation

|

|

| n.调查,调查研究 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

upwards

|

|

| adv.向上,在更高处...以上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

grizzly

|

|

| adj.略为灰色的,呈灰色的;n.灰色大熊 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

ornamented

|

|

| adj.花式字体的v.装饰,点缀,美化( ornament的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

relics

|

|

| [pl.]n.遗物,遗迹,遗产;遗体,尸骸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

jaw

|

|

| n.颚,颌,说教,流言蜚语;v.喋喋不休,教训 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

stratum

|

|

| n.地层,社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

descending

|

|

| n. 下行 adj. 下降的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

gnawed

|

|

| 咬( gnaw的过去式和过去分词 ); (长时间) 折磨某人; (使)苦恼; (长时间)危害某事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

carvings

|

|

| n.雕刻( carving的名词复数 );雕刻术;雕刻品;雕刻物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

advancement

|

|

| n.前进,促进,提升 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

gravels

|

|

| 沙砾( gravel的名词复数 ); 砾石; 石子; 结石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

gravel

|

|

| n.砂跞;砂砾层;结石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

chronological

|

|

| adj.按年月顺序排列的,年代学的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

intercourse

|

|

| n.性交;交流,交往,交际 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

walrus

|

|

| n.海象 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

everlasting

|

|

| adj.永恒的,持久的,无止境的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

Oxford

|

|

| n.牛津(英国城市) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

fowling

|

|

| 捕鸟,打鸟 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

darts

|

|

| n.掷飞镖游戏;飞镖( dart的名词复数 );急驰,飞奔v.投掷,投射( dart的第三人称单数 );向前冲,飞奔 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

shafts

|

|

| n.轴( shaft的名词复数 );(箭、高尔夫球棒等的)杆;通风井;一阵(疼痛、害怕等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

curiously

|

|

| adv.有求知欲地;好问地;奇特地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

analogous

|

|

| adj.相似的;类似的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

specimens

|

|

| n.样品( specimen的名词复数 );范例;(化验的)抽样;某种类型的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

friction

|

|

| n.摩擦,摩擦力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

tusks

|

|

| n.(象等动物的)长牙( tusk的名词复数 );獠牙;尖形物;尖头 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

harpooning

|

|

| v.鱼镖,鱼叉( harpoon的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

102

catching

|

|

| adj.易传染的,有魅力的,迷人的,接住 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

porpoises

|

|

| n.鼠海豚( porpoise的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

archers

|

|

| n.弓箭手,射箭运动员( archer的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

adorned

|

|

| [计]被修饰的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

browsing

|

|

| v.吃草( browse的现在分词 );随意翻阅;(在商店里)随便看看;(在计算机上)浏览信息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

backbones

|

|

| n.骨干( backbone的名词复数 );脊骨;骨气;脊骨状物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

worthy

|

|

| adj.(of)值得的,配得上的;有价值的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

interval

|

|

| n.间隔,间距;幕间休息,中场休息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

descended

|

|

| a.为...后裔的,出身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

marrow

|

|

| n.骨髓;精华;活力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

skull

|

|

| n.头骨;颅骨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

skulls

|

|

| 颅骨( skull的名词复数 ); 脑袋; 脑子; 脑瓜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

inevitable

|

|

| adj.不可避免的,必然发生的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

naturalist

|

|

| n.博物学家(尤指直接观察动植物者) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

formerly

|

|

| adv.从前,以前 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

prehistoric

|

|

| adj.(有记载的)历史以前的,史前的,古老的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

remarkably

|

|

| ad.不同寻常地,相当地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

fissure

|

|

| n.裂缝;裂伤 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

120

hippopotamus

|

|

| n.河马 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

migration

|

|

| n.迁移,移居,(鸟类等的)迁徙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

elevation

|

|

| n.高度;海拔;高地;上升;提高 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

fathoms

|

|

| 英寻( fathom的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

westward

|

|

| n.西方,西部;adj.西方的,向西的;adv.向西 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

125

tract

|

|

| n.传单,小册子,大片(土地或森林) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

126

isle

|

|

| n.小岛,岛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

127

isles

|

|

| 岛( isle的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

128

debouch

|

|

| v.流出,进入 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

129

watershed

|

|

| n.转折点,分水岭,分界线 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

130

shingle

|

|

| n.木瓦板;小招牌(尤指医生或律师挂的营业招牌);v.用木瓦板盖(屋顶);把(女子头发)剪短 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

131

littoral

|

|

| adj.海岸的;湖岸的;n.沿(海)岸地区 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

132

glaciers

|

|

| 冰河,冰川( glacier的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

133

eminent

|

|

| adj.显赫的,杰出的,有名的,优良的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

134

geologists

|

|

| 地质学家,地质学者( geologist的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

135

cavalry

|

|

| n.骑兵;轻装甲部队 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

136

migrations

|

|

| n.迁移,移居( migration的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

137

precisely

|

|

| adv.恰好,正好,精确地,细致地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

138

sustenance

|

|

| n.食物,粮食;生活资料;生计 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

139

varied

|

|

| adj.多样的,多变化的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

140

geographical

|

|

| adj.地理的;地区(性)的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

141

configuration

|

|

| n.结构,布局,形态,(计算机)配置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

142

encroachment

|

|

| n.侵入,蚕食 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

143

savages

|

|

| 未开化的人,野蛮人( savage的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |