Relation of Pleistocene to Prehistoric1 Period.—Magnitude of the Interval2.—Animals.—Physical changes.—Excavation3 and filling up of Valleys: Fisherton; Freshford.—Comparison of Deposits in Valleys with those of Caves.—Differences of Mineral Condition.—The Pleistocene Caves of Germany: Gailenreuth; Kühloch.—Of Great Britain.—The Caves of Yorkshire: Kirkdale.—Of Derbyshire: The Dream Cave.—Of North Wales, near St. Asaph.—Of South Wales, in counties of Glamorgan, Caermarthen, Pembroke.—Of Monmouth.—Of Gloucestershire.—Of Somersetshire: Uphill, Banwell, Bleadon, Sandford Hill, Wookey Hole.—The District of Mendip higher in Pleistocene age than now.—The condition of bones gnawed4 by Hy?nas.—The Caves of Devonshire: Oreston; Brixham; Kent’s Hole.—The probable age of the Machairodus of Kent’s Hole.—Those of Ireland, Shandon.

Relation of Pleistocene to Prehistoric Period.

We have seen, in the fifth and sixth chapters, that the caves offer valuable information as to the prehistoric ethnology of Europe, and that they prove the ancient neolithic5 population to stand directly related to the Basque and Celtic elements in the present inhabitants of Britain, France, and Spain. We shall discover in the course of this and the following chapters that no such265 continuity can be made out between the pal6?olithic man of the pleistocene age and any of the races now living in our quarter of the world; and we shall see that he is separated from his neolithic successor by an interval of time, the length of which cannot be measured in terms of years. Before the pleistocene group of caves be examined, it will be necessary to define the relation that exists between the prehistoric and the pleistocene periods.

The Animals—Magnitude of Interval.

The prehistoric mammalia consist, as we have seen (p. 136), with the solitary7 exception of the Irish elk8, of the wild animals at present living in Europe, together with the domestic species and varieties introduced by man, probably from central Asia. In the rest of this work we shall have to deal, not merely with the wild animals at present inhabiting Europe, but also with those which have either become extinct, or have migrated to Asia, America, or Africa. Besides this addition to the European fauna10 in the pleistocene age, the total absence of the domestic animals is a most important feature. The dog, goat, sheep, Celtic short-horn, and domestic swine are conspicuous11 by their absence: the reputed association of their remains12 with those of the pleistocene mammals being due, in all the cases which I have examined in France and Britain, to a confusion between distinct strata13 in the same cave or river-deposit, which are respectively of pleistocene and prehistoric or historic ages. Thus in the excavations14 in the gravel15 underneath16 London, the Celtic short-horn and goat of the superficial strata are very generally mixed with the266 reindeer17 and mammoth18 of the pleistocene gravels19 below, by the collectors, and the names of the domestic animals have crept into the pleistocene lists. None of the domestic animals have been recorded from any carefully explored strata of that age in any part of Europe.

The following late pleistocene species were unknown in Britain in the prehistoric age:—

Glutton21.

Spotted22 hy?na.

Panther.

Lion.

Lynx.

Felis Caffer.

Musk-sheep.

Bison.

Hippopotamus23.

Lemming.

Pouched24 marmot.

Tailless hare.

Lepus diluvianus.

Arvicola Gulielmi.

Cave-bear.

Rhinoceros25 hemit?chus.

R. tichorhinus.

Elephas antiquus.

Mammoth.

The glutton, lynx, bison, and lemming, still live in Europe, the spotted hy?na, Felis Caffer, and hippopotamus are peculiar26 to Africa, the lion to Africa and Asia, and the last seven species are extinct. The Machairodus cultridens and Rhinoceros megarhinus probably disappeared in an early stage of the pleistocene. It may reasonably be inferred, from the migration29 and extinction30 of so many species between the close of the pleistocene and beginning of the historic period, that the interval was of considerable length; for it would be impossible for such changes to have taken place in a short time.

The same sharp line of demarcation exists between the two faunas31 on the continent. The panther, Felis Caffer, lynx, spotted hy?na, musk-sheep, hippopotamus, and the extinct group disappeared. The African elephant forsook32 Spain and Sicily, the striped hy?na the south of France, before the prehistoric period; while the Elephas meridionalis and pigmy hippopotamus of Sicily, and267 the pigmy elephant and gigantic dormouse of Malta, became extinct. Speaking in general terms, the wild fauna of Europe, as we have it now, dates from the beginning of the prehistoric age, and consists merely of those animals which were able to survive the changes by which their pleistocene congeners were banished33 or destroyed. The arrival of the domestic animals under the care of man in the neolithic age, and their extension over the whole of Europe in a wild or semi-wild state, coupled with the disappearance34 of the wild species mentioned above, constitutes a change in the mammal life at least as important as any of those which define the meiocene from the pleiocene, or the pleiocene from the pleistocene periods.

Physical changes—The excavation and filling up of Valleys.

The magnitude of the interval between the two periods may also be gathered from the great changes which have taken place in physical geography. In nearly every valley in Great Britain, certain areas to be mentioned presently excepted, are strata of sand and gravel, proved to be of pleistocene age by their fossil mammals, and by their fluviatile shells to have been deposited by rivers. They occur at various heights, forming sometimes terraces, and at others isolated35 patches, which were accumulated when the river flowed at their level, and before the valleys were cut down to their present depth. Those at Fisherton near Salisbury, described by Sir Charles Lyell, Mr. Prestwich, Mr. John Evans,175 and others, may be taken as an example.

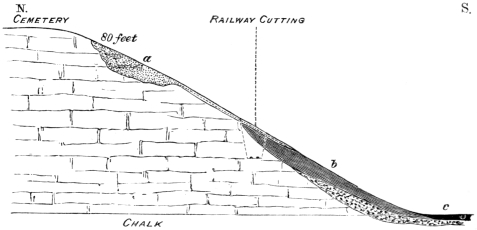

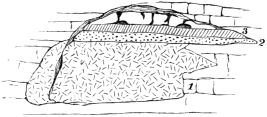

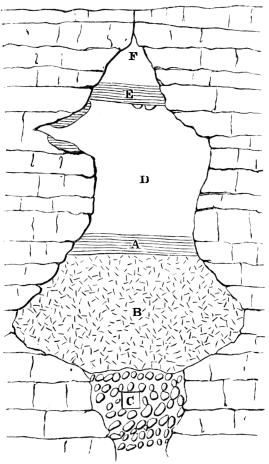

Fig36. 74.—Section of Valley-gravels at Fisherton. (Evans.)

The valley through which the river Wily flows is excavated37 in the chalk (Fig. 74), and on its northern side fluviatile deposits occur at two levels, represented in the accompanying section. One patch of gravel, about twelve feet thick, a, lies about eighty feet above the present level of the Wily; while a second, b, consisting of clayey brickearth or loam39, with seams of gravel, and fluviatile shells, sweeps down from a lower point to the bottom of the valley, and passes under the river. From the deposit a, Dr. Blackmore obtained many rudely-chipped implements41, of the same pal?olithic type as those found with the extinct mammalia in the gravel beds at Amiens and Abbeville in the valley of the Somme. In the deposit b, fossil mammalia were met with belonging to the following animals:—

Spotted hy?na.

Lion.

Reindeer.

Stag.

Bison.

Urus.

Musk-sheep.

Wild boar.

Horse.

Woolly rhinoceros.

Mammoth.

Lemming.

Pouched marmot.

Hare.

269 Dr. Blackmore subsequently discovered a flint implement40 along with these animals, of the same type as those previously42 met with in the deposit a.

A horizontal stretch of alluvium, c, deposited by the floods, occupies the present bottom of the valley. In this section it is plain that the gravels and brickearth at a and b were deposited by a river, which formerly44 flowed at those levels. In other words, the valley of the Wily was excavated during the time that the pleistocene strata a and b were being formed, while pal?olithic man and the extinct animals were living in the neighbourhood. The position also of b below the present bottom of the valley proves that the latter then was deeper than it is now. The prehistoric alluvium, c, represents the last stage in the history of the valley in which it is beginning to be filled with the deposits of floods. While it was being accumulated none of the animals of a and b were living in the district except the hare, urus, stag, horse, and wild boar.

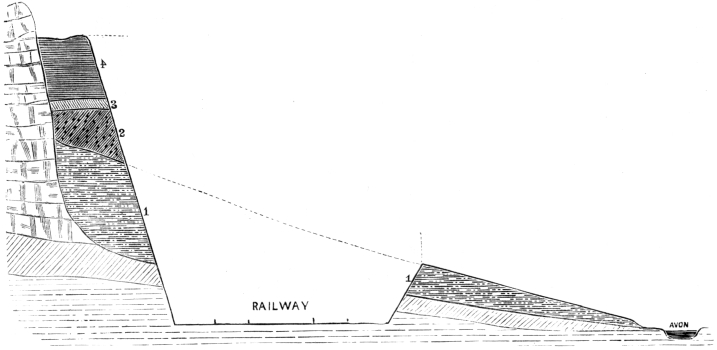

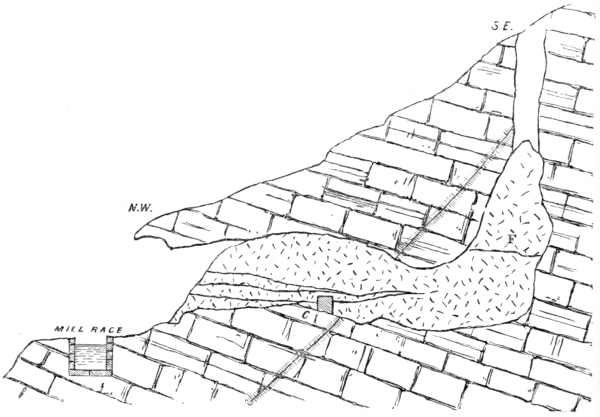

A somewhat similar section is exposed in the valley of the Avon at Freshford, near Bath, in a railway cutting, at a height of about thirty-five feet above the river. A thick mass of gravel abuts45 directly against a cleft46 of inferior oolite (Fig. 75), and gradually dies down to the alluvium. In it Mr. Charles Moore discovered the remains of the musk-sheep, and the Rev43. H. H. Winwood those of the mammoth, bison, horse, and reindeer. In this case the pleistocene strata occupied the side of one of the valleys which had been deepened since the time of their deposit.

Fig. 75.—Section of Valley-gravels at Freshford, Bath.

4, Red loam, 5ft. 6in.; 3, Oolitic wash, 1ft.; 2, Clay with flints, 4ft. 10in.; 1, Gravel with fossil mammals, 8ft.

The alluvium in the neighbourhood of Bath contains in its lower portion a layer of peat, with bones of the Celtic short-horn (Bos longifrons), stag, roe47, horse, goat, and pig; and in its upper part are old refuse heaps,270 proved to be Roman by the coins and ware48, which are also met with at various points underneath the surface soil, and sometimes at considerable depths. It is, therefore, of prehistoric and historic age, and since271 it is found only in the valley bottoms, we may conclude that the present courses of the rivers along the sides of which it is found date back from the prehistoric age; while their ancient courses are marked by the fluviatile deposits with the extinct mammalia standing49 at various levels, the higher being the older. In the section at Fisherton we have evidence that the river flowed at a lower level in the pleistocene age than in the prehistoric, and in that at Freshford that the lower portion of the valley had been excavated after the pleistocene strata had been formed. One or other of these physical changes is to be traced in nearly all river valleys.176 We may conclude that both imply a considerable lapse50 of time, because similar changes are now produced with extreme slowness. In the pleistocene river deposits, which lie scattered51 about at various heights on the valley sides, we seek in vain for neolithic implements, or domestic animals. In the low-lying alluvia, and accumulations of peat, we seek equally in vain for traces of pal?olithic man, or of the extinct mammalia, except the Irish elk.

We may also gather, from the localization of the prehistoric alluvia close to the present streams, that the time represented by its accumulation is insignificant52 in comparison with the long lapse of ages implied by the pleistocene gravels and brickearths, that were deposited at various heights during the excavation of the valleys. The general surface of the valleys has undergone but little change since history began, and the excavation by the rivers has been so small as to have escaped accurate measurement. The alluvia represent272 the principal work done since the close of the pleistocene period.

The most important testimony54 that the interval between the two periods was very long, is offered by the climatal change, and the severance55 of Britain from the continent. The arctic severity of the pleistocene winter in these latitudes56 had passed away before the prehistoric age, and the pleistocene valleys of the North Sea, St. George’s Channel, the British, and Irish Channels had been depressed57 beneath the waves of the sea before any prehistoric strata yet known had been deposited. The evidence that these changes actually took place must be referred to the two following chapters.

Comparison of Deposits in Valleys with those in Caves.

If these valley deposits be compared with the contents of some of the bone caves, such, for example, as those of the Victoria Cave (compare Figs58. 74 and 75 with Figs. 20, 21, 29), it will be seen that they present the same section. The pleistocene gravels and brick-earths of the one correspond with the lower strata of the other, and contain the same extinct animals. The prehistoric alluvium of the one is represented by the layer containing neolithic bronze or iron implements, as well as the same animals; while the historic strata are represented in both by the superficial accumulations. The only difference indeed between the one and the other is, that in the former the strata of the three periods are spread over a wide area, while in the latter they are super-imposed in vertical59 order, the pleistocene below, the prehistoric in the middle, and the historic on the surface.

273

Difference in Mineral Condition of Deposits in Caves.

The prehistoric, and the historic strata in caves differ from the pleistocene in their physical constitution. They are darker in colour, and more loosely stratified, and contain bones in a more friable60 and less mineralized condition, and are more free from stalagmite.

The Caves of Germany: Gailenreuth.

The use of fossil bones for medicinal purposes led, as I have already mentioned in the first chapter, to the exploration of caves, which were first scientifically examined in Germany towards the close of the eighteenth century. They abound61 in all the limestone62 plateaux, especially in the region of Franconia, and in that of the Hartz. Among them the most interesting, perhaps, is that of Gailenreuth, explored by Esper, Rosenmüller, Goldfuss, Buckland, Lord Enniskillen, and Sir Philip Egerton. It penetrates64 a lofty cliff, that forms a side of the deep gorge65 which the river Weissent has cut in the rock, at a point about three hundred feet above the water level.

The entrance, Dr. Buckland177 writes, is about seven feet high and twelve feet broad, and within it a short passage leads into two chambers66 (Fig. 76, A and B),178 hung with stalactites, and with the floors covered by a dense68 stalagmitic pavement, that has been more or less broken up by repeated diggings. These floors are perfectly274 horizontal, the level of that of B being considerably70 below that of A. They rest on an accumulation of reddish grey loam, containing pebbles72, and angular limestone blocks, and vast quantities of the bones and teeth of the animals formerly living in the district. The depth of this ossiferous deposit has not been ascertained73, but in the further end of the chamber67 B, it has been proved to be more than twenty-five feet thick.

Fig. 76.—Section of Gailenreuth Cave. (Buckland.)

The remains of the animals lie scattered in the wildest confusion; sometimes being completely matted together, but more generally each bone is enveloped74 in earth. They belong to the lion, the cave variety of the spotted hy?na, the cave-bear, grizzly75 bear, mammoth, Irish elk, and reindeer, as well as to those species which are still275 to be found in Germany, such as the glutton, brown bear, wolf, fox, and stag.

It is very difficult to account for such an accumulation as this, but it was probably introduced through the present entrance, and thence into the chamber B, passing from the higher to the lower levels. The teeth-marks on the bones show that some of the animals had formed the prey76 of the hy?nas, but had they introduced all the bones there would have been distinct strata marking the floors of occupation, as in Wookey Hole (Fig. 88). Moreover, no perfect skulls78, such as those of the bears, would have escaped their powerful teeth. The pebbles in the loam bear testimony to the passage of a current of water. And if we suppose that the cave was subject to floods, such as those in the water-caves described in the second chapter, the scattering79 of the bones through the loam may be explained. This, however, could not have happened had the cave then opened on the face of a nearly vertical cliff, and the only condition under which it would have been possible is, that the present entrance should have been directly connected with a stream flowing from the surface, that is to say, over the space now occupied by the gorge of the Weissent. If this view, advanced by Dr. Buckland, be accepted, the remoteness of the date of the filling up of the cave may be measured by the fact, that since that time the gorge has been cut down by the Weissent to a depth of more than 300 feet.

The stream by which the contents of the cave were introduced had a course probably analogous80 to that of Dalebeck (Fig. 6) and the remains of the animals were caught up from the surface, and accumulated in the276 subterranean81 chambers which it traversed. Their abundance offers no obstacle to this view, since wild animals frequent their drinking places in vast numbers, and fall a prey to the carnivora which lurk82 near the streams, and very many tumble into the natural pitfalls83, or swallow-holes, so universal in limestone districts.

The Cave of Kühloch.

Very many other caves occur in the neighbourhood, most of them, such as those of Zahnloch, celebrated84 for the abundance of fossil teeth, Mokas, Rabenstein, and others, of which the cave of Kühloch alone demands notice.

The cave of Kühloch is situated85 opposite to the castle of Rabenstein, in the gorge of the Esbach, at about thirty feet from the bottom. Its exterior86 presents a lofty arch in a nearly perpendicular87 cliff, about thirty feet wide and twenty feet high, and the entrance gradually leads into two large chambers “both of which terminate in a close round end, or cul-de-sac, at the distance of about 100 feet from the entrance. It is intersected by no fissures88, and has no lateral90 communications connecting it with any other caverns91, except one small hole close to its mouth, and which opens also to the valley.” The first thirty feet present a steep slope towards the entrance. Dr. Buckland describes the contents of the chambers in the following words:179—

“It is literally93 true that in this single cavern92 (the size and proportions of which are nearly equal to those of the interior of a large church) there are hundreds of cart-loads of black animal dust entirely94 covering the277 whole floor, to a depth which must average at least six feet, and which, if we multiply this depth by the length and breadth of the cavern, will be found to exceed 5,000 cubic feet. The whole of this mass has been again and again dug over in search of teeth and bones, which it still contains abundantly, though in broken fragments. The state of these is very different from that of the bones we find in any of the other caverns, being of a black, or, more properly speaking, dark umber colour throughout, like the bones of mummies, and many of them readily crumbling95 under the finger into a soft dark powder resembling mummy powder, and being of the same nature with the black earth in which they are embedded96. The quantity of animal matter accumulated on this floor is the most surprising, and the only thing of the kind I ever witnessed; and many hundred—I may say thousand—individuals must have contributed their remains to make up this appalling97 mass of the dust of death. It seems in great part to be derived98 from comminuted and pulverized99 bone; for the fleshy parts of animal bodies produce by their decomposition100 so small a quantity of permanent earthy residuum, that we must seek for the origin of this mass principally in decayed bones. The cave is so dry, that the black earth lies in the state of loose powder, and rises in dust under the feet; it also retains so large a proportion of its original animal matter that it is occasionally used by the peasants as an enriching manure101 for the adjacent meadows. I have stated that the total quantity of animal matter that lies within this cavern cannot be computed102 at less than 5,000 cubic feet; now allowing two cubic feet of dust and bones for each individual animal, we shall have in this single vault103 the remains of at least 2,500 bears, a number278 which may have been supplied in the space of 1,000 years by a mortality at the rate of two and a half per annum.”

Dr. Buckland’s explanation, that the cave was inhabited by bears for long generations, is probably true. The absence of pebbles and silt104 show that water had no share in the introduction of the remains; their preservation105 is due to the dryness of the cave, and to its proximity106 to the outer atmosphere.

The famous caves of Sundwig, Schartsfeld, and Bauman’s Hole, belong to the same class as Gailenreuth, and offer no differences which need be described.

These explorations establish the fact that, in the antediluvian107 age which we now term pleistocene, the lion, the cave-bear and grizzly bear, and cave-hy?na abounded108 in Germany, and that they sought as their prey not merely the wild animals now living in that region, but the reindeer, mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and Irish elk. All the discoveries in the German caves from the date of the exploration of Gailenreuth have merely verified this conclusion without adding any new fact of importance.

The Caves of Great Britain.

These discoveries in the German caves led to the exploration of those in our country. Dr. Buckland visited Gailenreuth in 1816, and in 1821 applied109 the result of his knowledge gained in Germany to the investigation111 of the famous cavern of Kirkdale.279180

The Hy?na-den28 at Kirkdale.

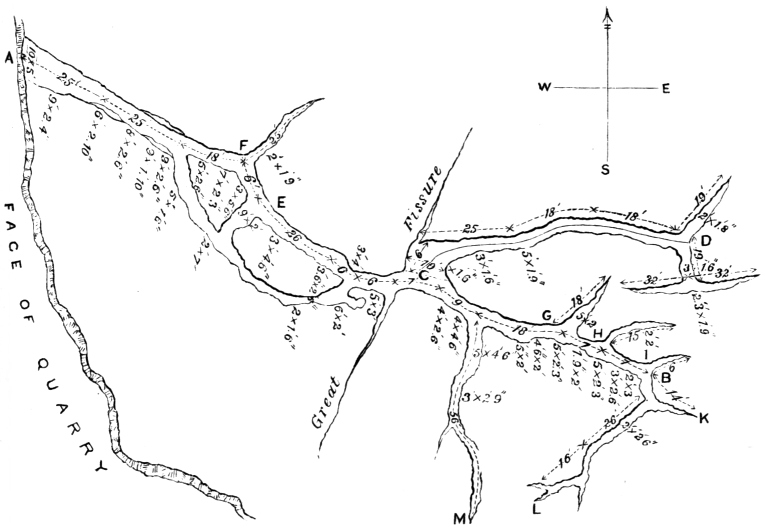

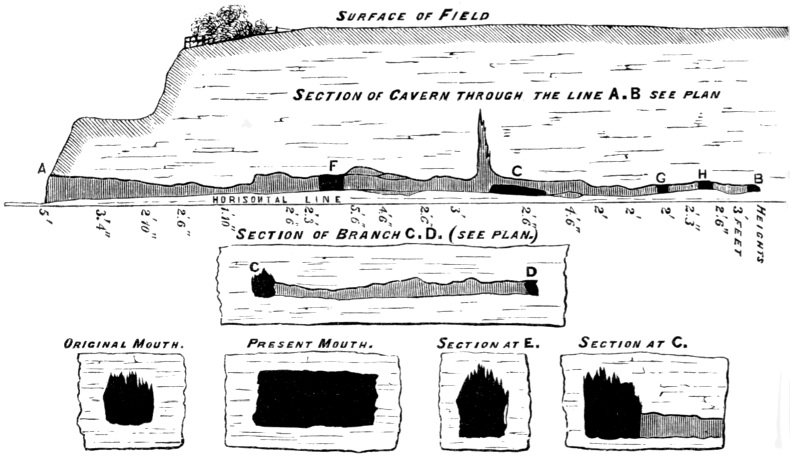

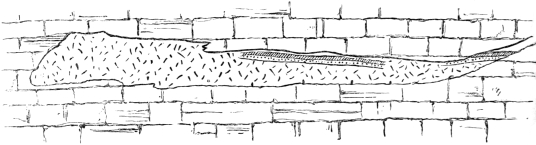

Fig. 77.—Plan of Kirkdale Cave. (Taylor.)

The cave of Kirkdale (Figs. 77, 78) was discovered in a quarry112 in the vale of Pickering, about twenty-five miles to the NN.E. of York, at a point where the dale of Holmbeck joins Kirkdale. The entrance, eighty feet above the valley bottom and twenty feet from the surface of the plateau above, was about three feet high and six feet wide, and led into a passage from five to ten feet wide, which ran nearly horizontally into the rock, and branched off into smaller ramifications113. Its general form and size may be gathered from the examination of the accompanying woodcuts, which were published by Mr. Taylor in “Macmillan’s Magazine,” in September 1862. The roof was for the most part free from stalactite, and there was no continuous coating of stalagmite on the280 floor, but merely here and there a few calcareous bosses termed “cows’ paps” by the workmen.

Fig. 78.—Sections of Kirkdale Cave. (Taylor.)

A layer of fine red loam covered the bottom, in the lower portions of which were large numbers of gnawed and broken bones, and teeth, for the most part of the same species as those formed in the German caves. In some places they were lying in little confused heaps, and in others, where the loam was thin, were exposed to the calcareous drip and cemented into a mass, their upper portions projecting through the stalagmite “like the legs of pigeons through pie-crust,” and their irregular distribution resembling that of the fragments scattered on the floor of a dog-kennel.

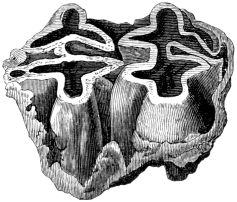

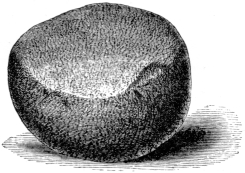

The remains of the animals were incredibly abundant, when the small space in which they were packed was taken into consideration. Those of the hy?na are estimated by Dr. Buckland as belonging to between two or three hundred individuals of all ages. The lion and the281 cave-bear, the wild boar, the hippopotamus (Fig. 79) an extinct kind of elephant (E. antiquus), and the rhinoceros named by Dr. Falconer R. hemit?chus, the reindeer, and Irish elk are also represented, but the species of most common occurrence are the bison and the horse. With a few exceptions all the bones with marrow114 were broken, and scarred by teeth, while the solid and marrowless115 were more or less perfect.

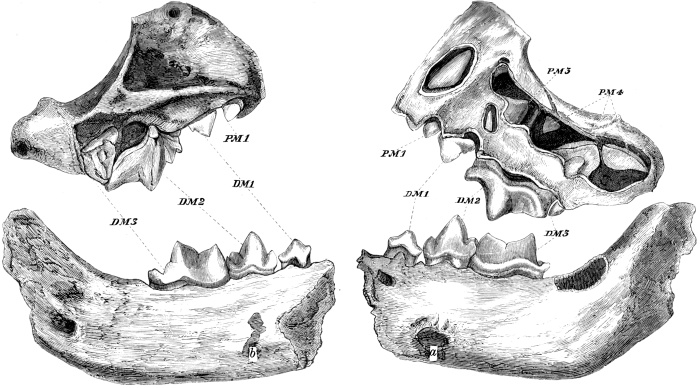

Fig. 79.—Molar of Hippopotamus. (Buckland.)

Dr. Buckland’s method of solving the problem of the introduction of remains of so many and different animals into so small a space, is a model of scientific analysis. He argues from the abundance of the remains of the hy?na, and from the correspondence of their teeth with the marks on the bones, and from the quantity of their coprolites, that the cave was inhabited by many generations of those animals, and that the gnawed fragments were relics116 of their prey. The hy?nas of the present day inhabit caves strewn with the bones of their prey, which are crushed by their powerful jaws118 into the same form as those of Kirkdale. He further demonstrated the truth of his conclusion by the crucial experiment of subjecting the leg-bone of an ox to a spotted hy?na from the Cape53 of Good Hope, in Wombwell’s Menagerie. “I was able,” he writes,181 “to observe the animal’s mode of proceeding119 in the destruction of bones: the shin-bone of an ox being presented to this hy?na, he began to bite off with his molar teeth large282 fragments from its upper extremity120, and swallowed them whole as fast as they were broken off. On his reaching the medullary cavity, the bone split into angular fragments, many of which he caught up greedily and swallowed entire: he went on cracking it till he had extracted all the marrow, licking out the lowest portion of it with his tongue: this done, he left untouched the lower condyle, which contains no marrow, and is very hard. The state and form of this residuary fragment are precisely121 like those of similar bones at Kirkdale; the marks of teeth on it are very few, as the bone usually gave off a splinter before the large conical teeth had forced a hole through it; these few, however, entirely283 resemble the impressions we find on the bones at Kirkdale; the small splinters also in form and size, and manner of fracture, are not distinguishable from the fossil ones. I preserve all the fragments and the gnawed portions of this bone, for the sake of comparison by the side of those I have from the antediluvian den in Yorkshire: there is absolutely no difference between them, except in point of age. The animal left untouched the solid bones of the tarsus and carpus, and such parts of the cylindrical122 bones as we find untouched at Kirkdale, and devoured124 only the parts analogous to those which are there deficient125. The keeper, pursuing this experiment to its final result, presented me the next morning with a large quantity of album gr?cum, disposed in balls, that agree entirely in size, shape, and substance with those that were found in the den at Kirkdale. The power of his jaws far exceeded any animal force of the kind I ever saw exerted, and reminded me of nothing so much as of a miner’s crushing mill, or the scissors with which they cut off bars of iron and copper126 in the metal foundries.”

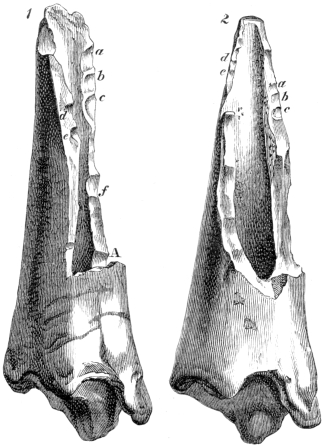

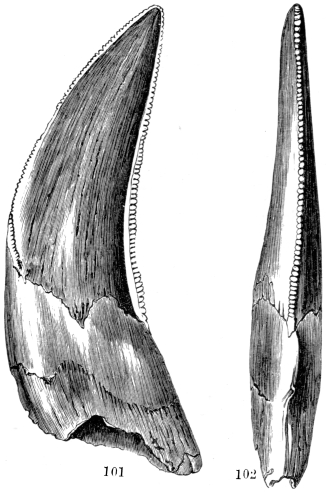

Fig. 80.—Leg-bones gnawed by Hy?nas—1, of Ox in Menagerie; 2, of Bison in Kirkdale. (Buckland.)

The exact correspondence of one of the fragments of the tibia of an ox, gnawed by the Cape hy?na, with the corresponding bone of the bison from Kirkdale, may be gathered from a comparison of the two figured in Fig. 80, in which the teeth-marks a, b, and c, are very distinct. The same kind of identity runs through the whole series of bones gnawed by the living and fossil hy?nas.

Dr. Buckland’s conclusion, that the Kirkdale cave was the den of the spotted hy?nas (H. crouta) that preyed127 upon the animals of Yorkshire in ancient times, and that it was undisturbed down to the time of its exploration,284 cannot be disputed. The tread of the hy?nas in their passage to and fro had polished some of the bones and jaws scattered on the floor, and the polished surfaces were uppermost, the rest of the fragments being rough. And Prof. Phillips informs me that the leg-bone of a ruminant was discovered wedged into a small fissure89 in the floor, with that portion which was within reach of the hy?na’s teeth gnawed away, while the rest was uninjured. The hy?na had lost his bone in the fissure, and was only able to nibble128 the end which projected. In these incidents we have a vivid picture of an hy?na’s den in Yorkshire during the pleistocene age, with the contents left in their natural order and not rearranged by the passage of water.

The Victoria cave near Settle, in Yorkshire, described in the third chapter, has also been occupied by hy?nas.

Caves of Derbyshire: the Dream-cave near Wirksworth.

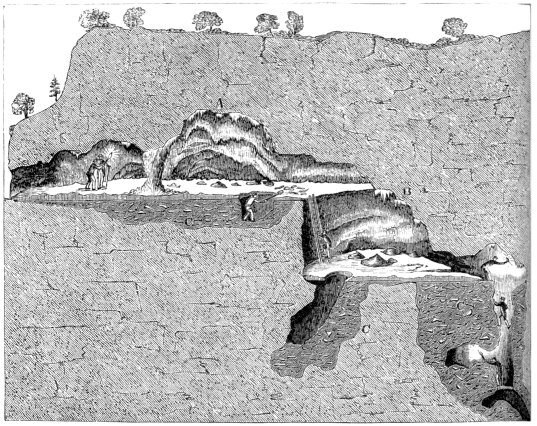

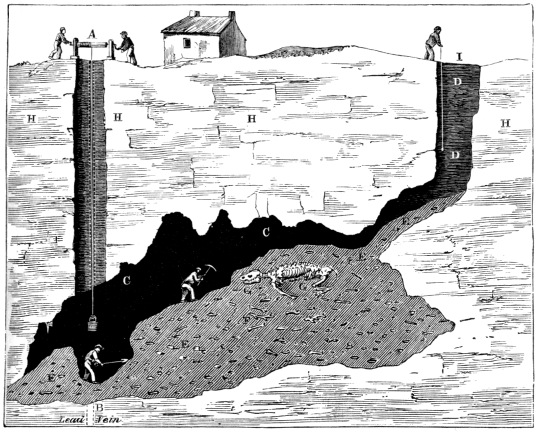

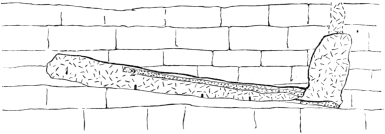

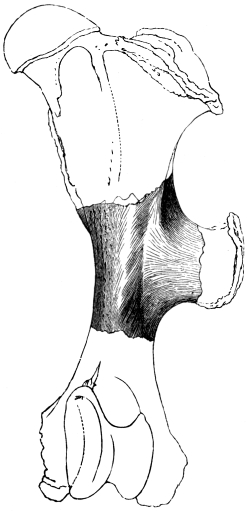

The Dream-cave, near Wirksworth,182 in Derbyshire, contrasts with that of Kirkdale in the perfect state of the bones which it contains. It was discovered in 1822, in following a vein129 of lead (Fig. 81). The miners suddenly broke into a hollow, c, filled with red earth and stones, and as they continued their shaft130 downwards131 the sides continually closed upon them until the roof of a cave was revealed. A nearly perfect skeleton of the rhinoceros was discovered in the earth, as well as bones of the horse, reindeer, and urus. After a large quantity of the earth had been removed, the surface soil, i, at a little distance began to sink, and ultimately a vertical shaft285 was found to connect the cave with the surface. Into this the animals had fallen, just as at the present time sheep and oxen frequently perish in similar natural pitfalls in the limestone strata.

Fig. 81.—The Dream-cave, Wirksworth. (Buckland.)

A Shaft following lead-vein.

B Supposed continuation of lead-vein.

C Cave.

D Swallow-hole.

E Ossiferous loam.

F Antler of deer.

G Rhinoceros.

H Limestone.

I Natural entrance.

Other caves and fissures in Derbyshire have yielded remains of the extinct animals: those of Balleye, near Wirksworth, and of Doveholes, near Chaple-en-le-Frith, the mammoth, and a small cave in Hartle Dale, near Castleton, explored by Mr. Pennington and myself in 1872, the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros.

286

The Caves of North Wales, near St. Asaph.

The ossiferous caves and fissures at Cefn, near St. Asaph, in the mountain limestone that forms the south side of the Vale of Clwyd, were first described in 1833,183 by the Rev. Edward Stanley, afterwards Bishop132 of Norwich, who explored that which Mr. E. Lloyd had discovered about half-way down the vertical cliff, in the grounds of Cefn Hall. It consists of a narrow passage, turning on itself, and communicating with the surface of the cliff by two entrances, which were completely blocked up with red silt, containing a vast quantity of bones in very bad preservation. The bottom has not yet been reached. In one portion I found, in 1872, a deposit of comminuted bone with scarcely any mixture of loam, that rose in clouds of dust as it was disturbed. The animals belonged to the same class as those of Germany, the cave-bear, spotted hy?na, and reindeer, as well as the hippopotamus, Elephas antiquus and Rhinoceros hemit?chus of the Kirkdale cave. Pebbles derived from the boulder133 clay, and rounded waterworn fragments of bone, showed that the contents had been introduced into this cave by a stream. Some of the remains, which were marked with teeth, may have been introduced by the hy?nas. The flint-flakes134 found with the human skull77 and cut antlers of stag, already referred to in the fifth chapter, were discovered in the lower entrance.

The same group of animals has been obtained by Mrs. Williams Wynn, the Rev. D. R. Thomas, and myself out of a horizontal cave at the head of the defile136 leading287 down from Cefn to Pont Newydd, in which the remains are embedded in a stiff clay, consisting of rearranged boulder clay, and are in the condition of waterworn pebbles. From it I have identified the brown, grizzly, and cave-bear. A further examination by the Rev. D. R. Thomas, and Prof. Hughes, has recently resulted in the discovery of rude implements of felstone, and a tooth which has been identified by Prof. Busk as a human molar of unusual size.184

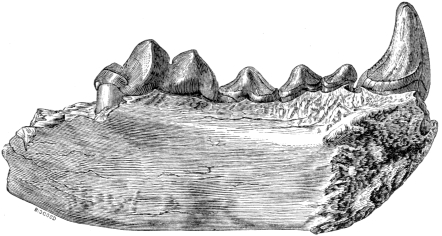

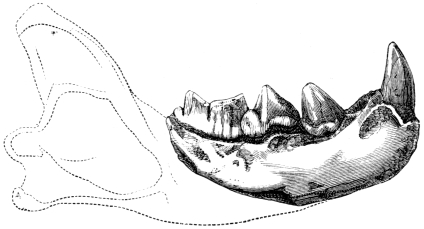

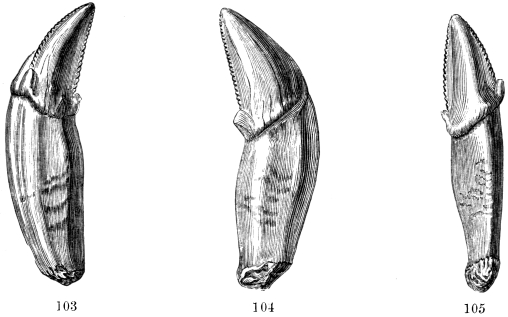

Fig. 82.—Left Lower Jaw117 of Glutton, Plas Heaton Cave.

A third cave in the neighbourhood at Plas Heaton, explored in 1870 by Mr. Heaton and Prof. Hughes, furnished the remains of the cave-bear, spotted hy?na, bison, and reindeer, and a remarkably137 fine specimen138 of the lower jaw of a glutton (Fig. 82), which I have described in the “Geological Journal” (vol. xxvii. p. 406). In a fourth cave, at Gallfaenan, the bear and reindeer were discovered. It is evident from the presence of numerous bones gnawed by hy?nas in these caves, that the valleys of the Clwyd and the Elwy were the favourite haunts of that animal in the pleistocene age.

288

Caves of South Wales in the counties of Glamorgan and Caermarthen.

The earliest cavern explored in South Wales is that of Crawley Rocks,185 Oxwich Bay, about twelve miles from Swansea. It was discovered in quarrying140 the mountain limestone in 1792, and contained the remains of the elephant, rhinoceros, ox, stag, and hy?na. It was completely destroyed before Dr. Buckland identified these animals in the collection of Miss Talbot of Penrice Castle.186

The line of cliffs, bounding the rocky peninsula of Gower, contains the cave of Paviland, described in the seventh chapter (p. 232), as well as the group explored by Colonel Wood of Start Hall, from the year 1848187 to the present time, Bacon Hole, Minchin Hole, Bosco’s Den, Devil’s Hole, Crow Hole, Raven’s Cliff, Spritsail Tor, and Long Hole, which are described by the late Dr. Falconer. The Rhinoceros hemit?chus was met with in comparative abundance, and in association with the woolly rhinoceros, mammoth, and E. antiquus. In Bosco’s Den there were no less than 750 shed antlers of reindeer; and in Long Hole, many flint-flakes were discovered in 1860 underneath the stalagmite, and in association with the extinct mammalia, which prove, as Dr. Falconer points out, that man inhabited that district in the pleistocene age.

These caves and fissures were at all levels in the cliff, and in some the bottoms were covered with a stratum141 of marine142 sand with sea shells, which showed that they had been washed by the sea before they had been filled by the ossiferous débris. Most of them had probably289 been filled by streams in the same manner as Gailenreuth and Wirksworth. They abound on the coast merely because a clear section has been worn by the waves. A straight cut through the rocks in any part of the district would probably show them to occur in equal abundance inland.

Caves in Pembrokeshire.

The patches of limestone on the opposite side of Caermarthen Bay, in the neighbourhood of Tenby, also contain ossiferous caverns. The Rev. G. N. Smith,188 of Gumfriston, has made a fine collection of bones and teeth of mammoth and hy?na, from a fissure in the Blackrock Quarry, close to Tenby, from a fissure in the cliff on Caldy Island, and from the Coygan cave in an outlier of limestone, near Pendine, and has discovered flakes of flint and of a peculiar hornstone in the “tunnel cave” termed the Hoyle, underneath stalagmite, in a stratum containing bones of the bear and reindeer. With the exception of the fissure in the Blackrock Quarry none of these have been fully20 explored. On a visit to Tenby, in 1872, I obtained many flint flakes, and bones broken by man, from the breccia in the Hoyle; and from a fissure on Caldy Island, numerous bones and teeth of young wolves, which represented a whole litter, and two metatarsals of bison, cemented together into a compact mass.

The discovery of mammoth, rhinoceros, horse, Irish elk, bison, wolf, lion, and bear, on so small an island as Caldy, indicates that a considerable change has taken290 place in the relation of the land to the sea in that district since those animals were alive. It would have been impossible for so many and so large animals to have obtained food on so small an island. It may therefore be reasonably concluded that, when they perished in the fissures, Caldy was not an island, but a precipitous hill, overlooking the broad valley now covered by the waters of the Bristol Channel, but then affording abundant pasture. The same inference may also be drawn143 from the vast numbers of animals found in the Gower caves, which could not have been supported by the scant144 herbage of the limestone hills of that district. We must, therefore, picture to ourselves a fertile plain occupying the whole of the Bristol Channel, and supporting herds145 of reindeer, horses, and bisons, many elephants and rhinoceroses146, and now and then being traversed by a stray hippopotamus, which would afford abundant prey to the lions, bears, and hy?nas inhabiting all the accessible caves, as well as to their great enemy and destroyer man. We shall see in the ninth chapter that the elevation147 of the whole district above its present level is part of the general elevation of north-western Europe, and no mere9 small or local phenomenon.

Cave in Monmouthshire.

King Arthur’s cave,189 on the side of a beautifully wooded knoll148, overlooking the valley of the Wye, near Whitchurch, in Monmouthshire, explored by the Rev. W. S. Symonds in 1871, is a hy?na den, like that of Kirkdale, containing the gnawed remains of the lion,291 Irish elk, mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and reindeer. Flint flakes, however, occurred in the undisturbed strata, which prove that it was also the resort of man. Mr. Symonds believes that the sand and gravel inside were deposited by the Wye, at a time when it flowed 300 feet above its present course, or before the valley was cut down to that depth. If this conclusion be true, the date of the occupation must be separated from the present day by a vast interval, which is only to be measured by the subsequent erosion of the valley by the slow operation of the subaerial agents, running water, ice, snow, and carbonic acid.

The only remains of the mammoth which I have examined belong to young individuals, and consist of the second and third milk-molars, a fact which I have very generally observed in hy?nas’ dens27. The older mammoths would not fall an easy prey to so cowardly an animal. The cave had also been inhabited by man after the pleistocene age, for coarse pottery149 of the neolithic kind, and flint flakes, were dug out of an upper stratum, while I was watching the excavation, in company with the Rev. W. S. Symonds, and the “Wanderers” field club.

Caves of Gloucestershire and Somersetshire.

The outliers of mountain limestone, on the southern side of the Bristol Channel, have long been known for their ossiferous caverns and fissures. From a fissure in Durdham Down,190 near Bristol, Mr. J. S. Miller150 obtained fragments of bones, about the year 1820, and among them Dr. Buckland notices the fossil joint151 of the hind-leg of a horse, the astragalus being held in natural position,292 between the tibia and the calcaneum, by stalagmite. Subsequently a large series of animals of the same species as those of Gower were discovered in it by Mr. Stutchbury, and are preserved in the Bristol Museum.

Caves of the Mendip Hills.

The caves of the Mendip Hills were known to contain bones as early as the middle of the eighteenth century, when that of Hutton,191 near Weston-super-Mare, was discovered in working the ochre and calamine which fills some of the fissures. The miners having opened an ochre pit, south of the little village of Hutton, discovered a fissure in the limestone full of good ochre, which they followed to a depth of eight yards, until it led into a cavern, the floor of which was formed of ochre, with large quantities of white bones on the surface, and scattered through its mass. Dr. Calcott describes the bones as projecting from the sides, roof, and floor of the excavation in such quantities as to resemble the contents of a charnel-house. Subsequently it was fully explored by the Rev. D. Williams, and Mr. Beard, of Banwell.

We owe the exploration of the neighbouring caves of Banwell, Sandford Hill, Bleadon, Goat’s Hole, in Burrington Combe, and Uphill,192 to the joint labours of the two above-mentioned gentlemen, extending over the period which elapsed between 1821 and 1860. The vast quantity of remains which they obtained can only be realized by a visit to the Museum of the Somerset Arch?ological and Natural History Society, at Taunton.293193 They belong to the same species as those already mentioned from the caves of South Wales. The fauna of the Mendip is, however, characterized by the great number of lions, and by a few fragments of the glutton. Of the former animal, Mr. Ayshford Sanford and myself have met with sufficient remains to figure nearly every portion of the skeleton, and the skulls prove that it was not a tiger, as it is considered to be by some naturalists152, but a true lion, differing in no respect, except in its large size, from those now living in Asia and Africa.

All these caverns consist of chambers at various levels more or less connected with fissures, and, from the perfect condition of the bones they must have been inaccessible153 to the bone-destroying hy?na. Their contents were introduced, as is suggested by Dr. Buckland, from the surface by streams falling into swallow-holes (see Fig. 81), which have now, under the changed physical conditions, ceased to flow.

The extraordinary quantity of remains preserved in one cave may be, to some extent, verified by a visit to that at Banwell. It consists of two large chambers, the upper one filled with thousands of bones of bison, horse, and reindeer, taken out of the red silt which originally filled it to the roof; the lower one full of the undisturbed contents, from which the bones project in the wildest confusion. This accumulation has been introduced by water, through a vertical fissure which opened on the surface. It is evident, from the very nearly perfect skulls of wolf and bear which were discovered, that the cave was not used as a den by the hy?nas. They are, however, proved to have been living close by at the time, since their skulls, and the gnawed antlers of reindeer, have been discovered294 inside. They were probably swept in by the stream along with the other bones.

The Uphill Cave.

The Cave of Uphill,194 discovered in 1826, by some workmen, and explored by the Rev. D. Williams, merits especial notice, from the peculiar conditions under which the remains of the extinct animals occurred. Like the other caves of the Mendips, it consists of fissures opening into chambers. In the upper part of one of these fissures were the remains of rhinoceros, hy?na, bear, horse, bison, and wild boar, imbedded in loam which rested on two large masses of limestone that had fallen so as to block up the fissure. Below this were no remains of the extinct animals, and the fissure ultimately led into a cave opening upon the line of cliffs. This latter had been inhabited within historic times, since many bones of sheep, or goat, and pieces of pottery, were met with, as well as a coin of the Emperor Julian. In this case, owing to the extraordinary accident of the fissure being blocked up by a fall of stone, the pleistocene accumulation is vertically154 above the historic; and had the barrier given way, Mr. Williams would undoubtedly155 have discovered the remains of the extinct mammalia, lying in a heap above the comparatively modern historic stratum. It seems to me very probable that some such accident may have caused the occurrence of the pleiocene machairodus in the Kent’s Hole cavern, in association with the pleistocene mammalia. In the long lapse of ages between the pleistocene and the present day, such accidents would be likely to occur in some295 few caverns, and we might expect to find remains of widely different ages, in certain exceptional cases, lying side by side, or even the older resting vertically over the newer. At all events we must conclude, that superposition, or association, cannot be rigidly156 enforced as tests of relative age in all ossiferous caverns.

The Hy?na-den of Wookey Hole.

The Hy?na-den of Wookey Hole,195 near Wells, on the south side of the Mendips, which I explored with the Rev. J. Williamson in 1859, and in the following years with Messrs. Willett, Parker, and Ayshford Sanford, is worthy157 of a more detailed158 notice, because it was among the first caverns in this country in which works of art were found under conditions that proved the co-existence of man with the extinct mammalia.

The ravine in which it was discovered, in 1852, is one of the many which pierce the dolomitic conglomerate159, or petrified160 sea-beach, of the Triassic age, resting at the foot of the cliffs from which it was torn by the waves, and overlying the lower slopes of the Mendips (see Fig. 1). Open to the south, it runs almost horizontally into the mountain-side, until closed abruptly161 northwards by a perpendicular wall of rock, 200 feet or more in height, ivy-covered, and affording a dwelling-place to innumerable jackdaws. Out of a cave at its base, in which Dr. Buckland discovered pottery and human teeth, flows the river Axe162, in a canal cut in the rock. In cutting this passage, that the water might be conveyed to a large paper-mill close by, the mouth of the hy?na-296den was intersected in 1852, and from that time up to December 1859 it was undisturbed save by rabbits and badgers163, and even they did not penetrate63 far into the interior, or make deep burrows164. Close to the mouth of the cave the workmen (employed in making this canal) found more than 300 Roman coins, among which were those of Allectus and of Commodus. When the Rev. J. Williamson and myself began our exploration, about twelve feet of the entrance of the cave had been cut away, and large quantities of the earth, stones, and animal remains had been used in the formation of an embankment for the stream which runs past the present entrance of the cave.

According to the testimony of the workmen, the bones and teeth formed a layer about twelve inches in thickness, which rested immediately upon the conglomerate-floor, while they were comparatively scarce in the overlying mass of stones and red earth. The workmen state also that at the time of the discovery of the cave the hillside presented no concavity to mark its presence. So completely was the cave filled with débris up to the very roof, that we were compelled to cut our way into it. Of the stones scattered irregularly through the matrix of red earth, some were angular, others water-worn; all are derived from the decomposition of the dolomitic conglomerate in which the cave is hollowed. Near the entrance, and at a depth of five feet from the roof, were three layers of peroxide of manganese, full of bony splinters, and, passing obliquely166 up towards the southern side of the cave and over a ledge110 of rock that rises abruptly from the floor: further inwards they became interblended one with another, and at a distance of fifteen feet from the entrance were barely visible. In297 and between these the animal remains were found in the greatest abundance.

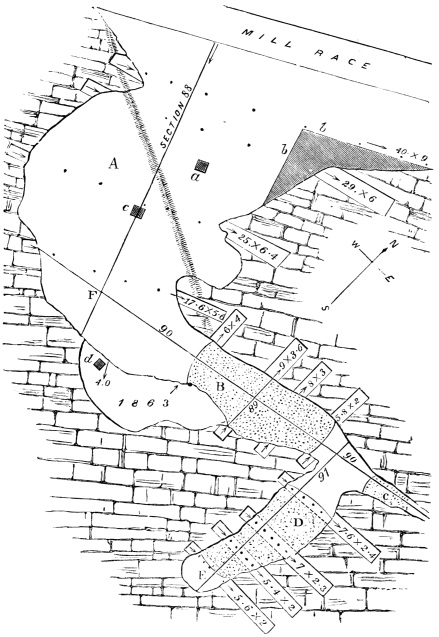

Fig. 83.—Plan of Hy?na-den at Wookey Hole.

Right lines = sections; dotted areas = bone-beds; shaded areas = ashes and implements.

While cutting our way inwards (Figs. 83 and 88), we found an angular piece of flint, which had evidently been chipped by human agency, and a water-worn fragment of a belemnite, which probably had been derived from298 the neighbouring marlstone rocks. Bones and teeth of the woolly rhinoceros, reindeer, stag, Irish elk, mammoth, hy?na, cave-bear, lion, wolf, fox, and horse rewarded our labours; and frogs’ remains, cemented together by stalagmite, were abundant at the mouth. The teeth preponderated167 greatly over the bones, and the great bulk were those of the horse. The hy?na-teeth also were very numerous, and in all stages of growth, from the young unworn to the old tooth worn down to the very gums. Those of the mammoth had belonged to a young animal, and one had not been used at all. The hollow bones were completely smashed and splintered, and scored with tooth-marks, while the solid carpal, tarsal, and sesamoid bones were uninjured, as in the Kirkdale Cave. The organic remains were in all stages of decay, some crumbling to dust at the touch, while others were perfectly69 preserved and had lost very little of their gelatine.

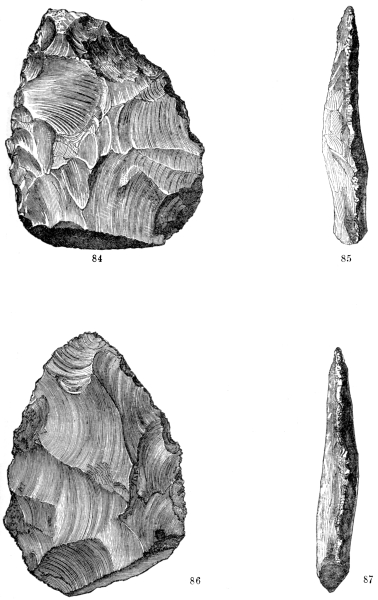

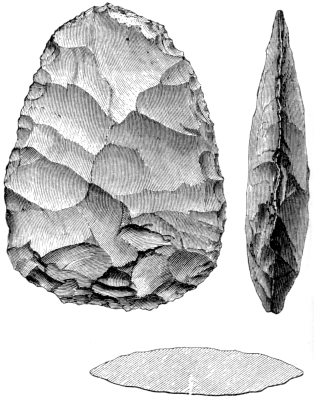

Figs. 84, 85, 86, 87.—Four Views of Flint Implements found in the Hy?na-den at Wookey Hole, near Wells.

In 1860 we resumed our excavations; and, in addition to the above remains, found satisfactory evidence of the former presence of man in the cave. Our search was rewarded by one oval implement of white flint, of rude workmanship (Figs. 84, 85, 86, 87), one chert arrow-head, a roughly-chipped and a round flattened168 piece of chert, together with various splinters of flint, which had apparently169 been knocked off in the manufacture of some implement. Two rudely-fashioned bone arrow-heads were also found, which unfortunately were subsequently lost by the photographer to whom they were sent; they resembled in shape an equilateral triangle with the angles at the base bevelled off. All were found in and around the same spot, in contact with some hy?na-teeth, between the dark bands of299 manganese, at a depth of four feet from the roof, and at a distance of twelve feet from the present entrance (Fig. 83, a).

That there might be no mistake about the accuracy of the observations, I examined every shovelful170 of débris as it was thrown out by the workman; while the exact spot where they were excavating171 was watched by my colleague. The figured implement was picked out of the undisturbed matrix by him; the rest were found by me in the earth thrown out from the same place.

The lines of peroxide of manganese must have been accumulated on the old floors of the cave, because they were associated with numerous splinters and gnawed animal remains; and there can be no doubt that the latter were introduced by the hy?nas. Those animals have a peculiar habit, as Dr. Buckland proved by experiment, of gnawing172 similar bones in precisely the same way; and a comparison of the relics of the meals of the hy?nas in the Zoological Gardens with those in the cave, shows that the latter have passed between the jaws of a like animal that once inhabited Somersetshire. Coprolites of the same animal were very abundant, and in some places formed a greyish-white layer of phosphate of lime. There were also other equally unmistakeable traces of the animal in fragments of bone, polished by their tread, as in the Kirkdale cave. It is, therefore, only reasonable to suppose that these remains of animals were brought into the cave from time to time by hy?nas, and left on the floors. That they were not introduced by water is proved by the preservation of the delicate processes and points of bone, which would certainly have been broken in transitu. Since, then, the implements, which, beyond doubt, had been fashioned by man, were301 underneath one of these old floors, it was certain that man was contemporary in the district with the hy?na and the animals on which it preyed, and the fact that they were found only on one spot implies that they were deposited by the hand of man. To suppose that a savage173 would take the trouble to excavate38 a trench174 twenty-four feet long—for twelve feet of the former mouth of the cave had been cut away—with miserable175 implements, and consequently with great labour, and having excavated it again to fill it up to the very roof, is little less than absurd. Nor could such an operation take place in such a deposit, without the stratification of the layers being destroyed. The absence of pottery and human bones precludes176 the idea of the cave ever having been a place of sepulture, such as Aurignac or Bruniquel. This discovery, therefore, of itself stamps the contemporaneity of man with the extinct mammalia, and following close on the similar discoveries in Brixham cave, to be mentioned presently, puts the question beyond all doubt.

In April 1861 we resumed our excavations; and, as we made our way inwards, found that the cave began to narrow, and ultimately to bifurcate177, one branch extending vertically upwards178, while the other appeared to extend almost horizontally to the right hand. As we reached the middle constricted179 passage, the teeth became fewer, while the stones were of larger size than any that we had hitherto discovered. The great majority of the gnawed antlers of deer were found at this part, also the posterior half of a cervine skull, the right upper jaw of wolf, and, what is more remarkable180, a stone with one of its surfaces coated with a deposit apparently of stalagmite: this, however, was much lighter181 than stalagmite, and not so good a conductor of heat; and, on analysis,302 I found that it consisted of phosphate of lime, with a little carbonate, and a very small portion of peroxide of manganese. Doubtless the surface of the stone, covered with phosphate of lime, formed part of the ancient floor of the cave, and hence was coated with album gr?cum; while the lower part, being imbedded in the earth on the floor, was not so coated. This deposit may, perhaps, explain the absence of round balls of coprolite, which, assuming that the cave at the time was more damp than that at Kirkdale, would be trodden down on the floor by the hy?nas, instead of presenting a rounded form. The stone also itself exhibits tooth-marks underneath the coating of album gr?cum, and probably was gnawed by the hy?nas, like the antlers, for amusement. This discovery proves that violent watery182 action had but small share, if any, in filling the cave; for in that case the soft covering would have been removed from the stone. Similar evidence is offered by the wonderful preservation of some of the more delicate fragments of bone, such as the palatine process of the maxilla of the wolf.

The section made in cutting this passage presented irregular layers of peroxide of manganese, full of bony splinters, and each more or less covered by a layer of bones in various stages of decay. These layers were absent from the upper portion of the passage. There were masses of prisms of calc-spar scattered confusedly through the matrix. After excavating the vertical branch as far as we dared (for the large stones in it made the task dangerous), we were compelled to leave off, having penetrated183 altogether only thirty-four feet from the entrance. No flint implements rewarded our search this year. Teeth were far more numerous than303 bones, probably because they are more durable184 as well as because of their rejection185 by the hy?nas. One jaw was bitten in two, and the fragments found about a foot apart in the undisturbed matrix, just as they had been dropped from the mouth of the hy?na.

In the spring of 1862 Mr. Parker, Mr. Willett, and myself resolved to verify the association of articles of man’s handiwork along with the extinct mammalia, by cleaning out the cave, which was courteously186 placed at our disposal by the owner, Mr. Hodgekinson.

Our first task was to clear the contents out of the portion of the cave nearest the mouth, or the antrum (Fig. 83, A), and as we excavated onwards many traces of the presence of man were met with. A wide area on the left-hand side (b), where the roof and floor of the cave gradually met together, furnished innumerable fragments of charcoal187, and many flint implements associated with the remains of the horse, rhinoceros, and hy?na. One fragment of bone in particular, belonging to the rhinoceros, had been calcined, and its carbonized condition bore unmistakeable testimony that it had been burnt while the animal juices were present. There were many other bones also burnt, which indicated the place where fires had been kindled188, and food cooked. As we dug our way forward we met with a third area (c), that furnished flint and chert implements under the same conditions of deposit as that which tempted189 us to carry on our excavations. Its relation to the old floors of hy?na-occupation is shown by the dark lines over the area c in Fig. 88. At last the large open chamber (A) was cleared; it measured about thirty feet wide by six feet high, and it extended forty feet inwards. On the left there was a small upward-turning passage, very nearly304 blocked up with a mass of stalagmite; at the farther end a vertical fissure extended upwards (F), to the surface. This fissure has subsequently been proved to extend downwards to the right, and will doubtless furnish large quantities of animal remains to future explorers.

Fig. 88.—Section through A of Fig. 83, showing contents of Hy?na-den.

c = flint implements; thick lines above = old floors.

Fig. 89.—Transverse Section through B of Fig. 83.

1 = red earth; 2 = bone-bed; 3 = dark earth.

The large chamber now turned abruptly to the left, and we gradually worked our way into a small horizontal passage about four feet high. Here there was an interval of from three to four inches between the roof and contents, traversed by stalactites, which in some places formed a smooth undulating drapery with stony190 tassels191, and in others tiny pillars extending down to the débris, and, as it were, propping192 up the roof. These pedestals (see Fig. 15) gradually expanded into round plates of stalagmite, which sometimes met and formed a continuous crust. In some places an infiltration193 of carbonate305 of lime had cemented organic remains, stones, and earth into a hard mass, which had to be broken up with gunpowder194 before it could be removed out of the cave. The excitement of extracting from these blocks their treasures was of the very keenest, for we could not tell what a stroke of the hammer would reveal. Sometimes an elephant’s tooth suddenly came to light, at others a hy?na’s jaw, or a rhinoceros’ tooth, or the antler of a reindeer, or the canine195 of a bear. The bones were so numerous that they scarcely attracted attention. In one fragment of this breccia, now in the Brighton Museum, are a tusk196 and carpal of mammoth, the right ulna of the woolly rhinoceros, and an antler of reindeer. In a second, two shoulder-blades and two haunch bones of the woolly rhinoceros, with a coprolite and lower jaw of cave hy?na. As the men removed the large blocks they were brought to the mouth of the cave to be broken up by our smaller instruments. Presently the passage narrowed to about six feet, and presented the following section (Fig. 89). On the floor of the cave there was a layer of red earth two feet in thickness, and, as usual, containing a few organic remains and many stones (Fig. 89, 1). Upon this rested a most remarkable accumulation of bones, and teeth, matted306 and compacted together, from three to four inches thick, and extending horizontally from one side of the passage to the other (Fig. 89, 2). Next came a layer of dark red earth (Fig. 89, 3), loose and friable, three to four inches thick, supporting in its surface a few rounded stalagmites, and a few stalactitic pillars, that spanned the interval of from three to four inches between it and the roof. This bone-bed was about seven feet wide and fourteen feet long, affording, therefore, a square area of ninety-eight feet (see dotted area B Fig. 83, and in Fig. 90). The enormous quantity of the remains of animals present cannot fairly be estimated even by the large number preserved, because most of the bones were as soft as wet mortar197. The five hundred and fifty specimens198 obtained must be looked upon merely as a small fraction of the whole.

Fig. 90.—Longitudinal Section through B and C of Fig. 83, showing bone-beds.

Dotted area = bone-bed.

We presently passed beyond the bone-bed, and found that the passage bifurcated199 (Fig. 83, C and D), the smaller branch going straight forwards and gently upwards (Fig. 90), while the larger stretched at right angles from it and passed gently downwards. In the former there was a second bone-bed similar in every respect to that already described, which continued undiminished in thickness until it rested directly on307 the floor. It afforded a square area of about fifteen feet. The passage was about sixteen inches high and three feet wide, and gradually narrowed until at a distance of twelve feet from the bifurcation a stalactite six inches long reached the floor and formed a vertical bar, as if to forbid another ingress. When this had been explored as far as we could crawl, the larger branch (Fig. 83, D, and Fig. 91) engaged our attention, and we soon discovered a third layer of bones of the same character as the others, and in the same position, excepting that in some places it was in immediate165 contact with the roof. In width it was six, in length fourteen, and in square area eighty-four feet. From its further end to the termination of the passage there was not the slightest vestige200 of bones or teeth, and a stiff grey clay rested on a horizontal layer of sand on the floor. Here the passage suddenly turned upwards until it became so small and barren that it was not worth our while to pursue it farther. It doubtless rises to the surface, like the large fissure opposite the entrance of the cave shown in Fig. 88.196

The exploration was resumed the following year by Mr. Ayshford Sanford and myself, and yielded vast308 quantities of fossil remains. We cleared out the space marked 1863 in the plan, and discovered a flint implement at the point marked d, in Fig. 83. My friend the late Mr. Wickham Flower has also worked the cave, more particularly at the right-hand side of the entrance chamber.

The ashes and implements were found in positions, near the mouth of the cave, where man himself may have placed them (see Figs. 83, 88), with the exception of the flint implement at d, and an ash of bone imbedded in the earthy matrix between the canine tooth and a coprolite of the hy?na, and cemented to a fragment of dolomitic conglomerate. This was found far in the cave, either at the entrance of the passage B, or in the middle of the passage D. The latter passage yielded the only rolled flint without traces of man’s handiwork. The materials out of which the implements were made were used pretty equally. All those, like Fig. 84, were of flint; all those chipped into a rounded form and flat-oval in section of chert from the Upper Greensand; while the flakes consisted of both used indifferently. Besides these three typical forms, which were most abundant, is a fourth, in form roughly pyramidal, with a smooth and flat base, and a cutting edge all round. Of these we found but two examples, both consisting of chert. In form they are exactly similar to several hundreds found in a British village at Stanlake, in Berkshire, and to those I discovered in a cemetery201 of the same age at Yarnton, near Oxford202. They strongly resemble a cast I have of one found by M. Lartet in the cave of Aurignac. Were it not for this similarity, I should look upon them as cores from which flakes had been struck. The rest309 are mere splinters, irregular in form, and probably made in the manufacture of the various flint and chert implements. All the flint implements have been altered in colour and structure, either by heat or, as is more probable, by some chemical action. Without exception, the old surfaces present a waxy203 lustre204 (by the absence of which forgeries205 are easily detected), the colour is of a uniform milk-white, and the ordinary conchoidal fracture is replaced by that of porcelain206. Some are not harder than chalk. I have met with weathered and calcined flints in Sussex in which similar changes are observable, and in which the difference in the results of chemical action and heat can hardly be detected. The chert implements, on the other hand, show no traces of any such changes, but are similar in colour and structure to the rocks from which they came—the Upper Greensand of the Blackdown Hills.

All the fragments of calcined bone, with the exception of one already mentioned, were found near the entrance (see Fig. 83, b), and in a place more suitable for a fire than any other in the cave. I can identify none of them as human. The coarse texture207, the structure, and the thickness of one indicate a fragment of a long bone of the rhinoceros.197 All resemble many splinters strewn about in other parts of the cave, which are not calcined, but were evidently introduced by the hy?nas. The calcination may therefore be due to the accident of their lying upon the surface at the time the fire was kindled.

The remains obtained in 1862–3 from three to four thousand in number, afford a vivid picture of the animal life of the time in Somerset. They belong to the following310 animals, the numbers representing the jaws and teeth only, and the implements:—

Man 35

Cave-Hy?na 467

Cave-Lion 15

Cave-Bear 27

Grizzly Bear 11

Brown Bear 11

Wolf 7

Fox 8

Mammoth 30

Woolly Rhinoceros 233

Rhinoceros hemit?chus 2

Horse 401

The Great Urus 16

Bison 30

The Irish Elk 35

Reindeer 30

Red Deer 2

Lemming 1

The remains of these animals were so intermingled that they must have been living together at the same time. They lie large with small, the more with the less dense, and are not in the least degree sorted by water. There is no evidence of the hy?na succeeding to the cave-bear, or the reindeer to the urus, or that the bears came here to die, as in some of the German caves, or that the herbivores fell, or were swept into open fissures, and left their remains, as in the caves of Hutton and Plymouth. On the contrary, the numerous jaws and teeth of hy?na, and the marks of those teeth upon nearly every one of the specimens, show that they alone introduced the remains that were found in such abundance. And they preyed not merely upon horses, uri, and other herbivores, but upon one another (Figs. 92, 93), and they even overcame the cave-bear and lion in their full prime. Some of the bones of the larger animals, and in particular a leg-bone of a gigantic urus, have been broken short across and not bitten through—a circumstance which points towards one of the causes of the vast accumulation of bones in so small a cave. It is well known that wolves and hy?nas311 at the present day are in the habit of hunting in packs, and of forcing their prey over precipices208. The Wookey ravine is admirably situated for this mode of hunting, and would not fail to destroy any animal forced into it from the hill-side. It is therefore very probable that the hy?nas sometimes caught their prey in this manner. They would not have dared to attack the bears and lions unless these had been disabled.

Fig. 91.—Longitudinal Section through D of Fig. 83.

Dotted area = bone-bed.

But if all the remains of the animals were introduced by the hy?nas, they certainly in some cases do not occupy the exact position in which they were left by those animals. One of the bone layers (Fig. 91) for instance, actually touched the roof. This, indeed, has been used as an argument in favour of their having been introduced by water, from some unknown repository. But if this hypothesis be admitted, we are landed in the following dilemma209: either the introducing current of water must have passed down the vertical passages, or upwards through the horizontal mouth of the cave. In the former case the three bone layers would not have been found in the narrow passages, but would have been swept out into the wide chamber, where the force of the hypothetical current must have abated210. In the latter case the great bulk of the remains would have312 been found in the chamber, and not in the smaller passages. Moreover, the absence of marks of transport by water, and especially of that sorting action which water as a conveying agent always manifests, renders the view of their being so introduced untenable. On the other hand, the horizontality of the layers of bone, and the presence of sand and of red earth, imply that water was an agent in re-arranging the bones and in introducing some of the contents of the cave. The only solution of the difficulty that I can hazard is the occurrence of floods from time to time, during the occupation of the hy?nas, similar to those which now take place in the caverns of the neighbourhood. A few years ago, the outlet211 of the Axe in the great cave was partially212 blocked up, and the water rose to a height of upwards of sixteen feet, leaving a horizontal deposit of red earth of the same nature as that in the hy?na-den. Now if we suppose that similar floods were caused by an obstruction213 in the ravine below the hy?na-den, it may have been flooded, just as the upper galleries of the great cave, and the water laden214 with sediment215 might have elevated the layers of matted bone, and some of the scattered remains on the surface, while the current was insufficient216 to disturb the stones, or to affect to any extent the deposits of former floods. The buoyancy of the organic remains is not required to be greater, on this hypothesis, than in that of their having been introduced by a current through the vertical passages. Some of the wet bones taken straight from the cave were sufficiently217 light to be carried down by the current of the Axe.

All these facts taken together enable us to form a clear idea of the condition of things at the time the hy?na-den was inhabited. The hy?nas were the normal occupants313 of the cave, and thither218 they brought their prey. We can realize those animals pursuing elephants and rhinoceroses along the slopes of the Mendip, till they scared them into the precipitous ravine, or watching until the strength of a disabled bear or lion ebbed219 away sufficiently to allow of its being overcome by their cowardly strength. Man appeared from time to time on the scene, a miserable savage armed with bow and spear, unacquainted with metals, but defended from the cold by coats of skin.198 Sometimes he took possession of the den and drove out the hy?nas; for it is impossible for both to have lived in the same cave at the same time. He kindled his fires at the entrance, to cook his food, and to keep away the wild animals; then he went away, and the hy?nas came to their old abode220. While all this was taking place there were floods from time to time until eventually the cave was completely blocked up with their deposits.

Fig. 92.—Gnawed jaw of Hy?na, from Hy?na-den at Wookey (1/2).

Dotted outline = portion eaten.

314 The winter cold at the time must have been very severe to admit of the presence of the reindeer and lemming.

The district of the Mendip Hills at a higher level than now.

When we reflect on the vast quantities of the remains of the animals buried in the caves of so limited an area as the Mendip Hills, it is evident that there must have been abundance of food to have enabled them to live in the district. The great marsh221 now extending from Wells to the sea, and cutting off the Mendips from the fertile region to the south, was probably a rich valley at a higher level than at present, joining the westward222 plains now submerged under the Bristol Channel. An elevation of from 100 to 300 feet would produce the physical conditions necessary for the sustenance223 of the herbivora found in the caves both in South Wales and Somersetshire.

The characters of a Hy?na-den.

Fig. 93.—A and B, upper and lower jaws of Hy?na-whelp, Wookey.

The remains of the animals which have been eaten by the cave-hy?na, may be recognized by the following characters. All are more or less scored by teeth, and the only perfect bones are those which are solid, or of very dense texture. The skulls are represented merely by the harder portions. That of the woolly rhinoceros, for example, by the hard pedestal which supports the anterior224 horn (see Fig. 30). Several of these pedestals occurred in the Wookey hy?na-den. The lower jaws also have lost their angle and coronoid process, and are gnawed to the pattern of the shaded portion of Fig. 92, the less succulent part bearing the teeth being rejected.315 This holds good of the jaws of all the animals so persistently225, that out of more than two hundred from Wookey there was only one exception. The jaw of the glutton (Fig. 82), from Plas Heaton, is also gnawed to the same shape, and one of those of the cave-bear from the cavern of Lherm, considered by M. Garrigou to have been fashioned by the hand of man into an implement, seems to me, after a careful comparison in company with Dr. Falconer, referable solely226 to the gnawing of the hy?na. In Fig. 92, the lower jaw of an adult hy?na is represented, and in Fig. 93 (1) the upper and lower jaws of a hy?na-whelp. In the latter the teeth marks a and b are remarkably distinct.199

Fig. 94.—Left Thigh227-bone of Woolly Rhinoceros gnawed by Hy?nas; Shaded parts left. (Wookey Hole.)

The marrow-containing bones are also universally splintered away, until either the articular ends alone are left, as in Fig. 80, or in some cases, as in that of the femur of woolly rhinoceros (Fig. 94), the dense central portion bearing the third trochanter is preserved. This fragment is extremely317 abundant in nearly all the hy?na-caves in this country. From the invariable habit of the hy?na leaving the bones of its prey in fragments of this kind, their dens are characterized by the absence of perfect long-bones and skulls, and consequently, when these occur in a cave it is certain proof that it was not occupied by these animals. In a great many caves, however, the gnawed fragments are associated with the perfect bones, as, for example, at Banwell, a circumstance that may be accounted for by the untouched carcases and the gnawed fragments being swept in from the surface by a stream falling into a swallow-hole. In all hy?na-dens also are large quantities of album gr?cum, as well as fragments of bone more or less polished by the friction228 of the hy?na’s feet.

The Caves of Devonshire.

The ossiferous caves on the south coast of Devonshire, explored during the last fifty years, are by far the most important in this country, since they were the first which were scientifically examined, and the first which established the co-existence of man with the extinct mammalia.

We owe the full details of their history to the labours of the distinguished229 cave-hunter Mr. Pengelly, F.R.S.,200 whose writings are freely used in the following account.

The Oreston Caves.

The first intimation of the presence of fossil bones in the district was furnished by Mr. Whidbey, the engineer318 in charge of the construction of the Plymouth breakwater, who discovered numerous bones and teeth, imbedded in clayey loam, in some cavernous fissures at Oreston, which were brought before the Royal Society by Sir Everard Home in 1817. Thus Dr. Buckland’s researches in Kirkdale were anticipated by four years. From time to time, since that date, several other fissures and caves close by have furnished remains of rhinoceros, mammoth, hy?na, lion, and other animals. Among the bones and teeth originally sent up by Mr. Whidbey are several which were identified by Prof. Busk,201 as belonging to the Rhinoceros megarhinus, a species that is vastly abundant in the pleiocene strata of northern Italy and is also represented in the early pleistocene forest-bed of Norfolk and Suffolk, and in the lower brickearths of the valley of the Thames at Grays and Crayford. This is the only case on record of the discovery of the animal in a cavern deposit.

The cavernous fissures in the neighbourhood of Yealmpton,202 about seven miles east-south-east from Plymouth, explored by Mr. Bellamy and Colonel Mudge, R.A., F.R.S. in 1835–6, contained the remains of the hy?na and rhinoceros, and the other animals more usually associated with them. They were probably filled, as in the case of Oreston, mainly by the streams which introduced the pebbles. They may, however, from time to time have been inhabited by the hy?nas, although the presence of three skulls of that animal forbids the supposition that they dragged in all the fossil bones.

319

The Caves at Brixham.

The series of fissures accidentally discovered in 1858, in quarrying the rock which overlooks the little fishing town of Brixham, known as the Windmill cave, was selected by the late Dr. Falconer,203 as a spot in which thorough investigation would be likely to decide the then doubtful question of the co-existence of man with the extinct mammalia. Kent’s Hole had been disturbed by repeated diggings, and the results might be viewed with suspicion. He, therefore, urged the importance of a systematic230 examination of this virgin231 cave with such effect, that it was undertaken by the Royal and Geological Societies, and a committee was appointed, comprising, amongst others, Dr. Falconer, Prof. Ramsay, Mr. Prestwich, Sir Charles Lyell, Prof. Owen, Mr. Godwin-Austen, and Mr. Pengelly. To the superintendence of the last is mainly due the minute care with which the exploration was conducted. The remains have been identified by Dr. Falconer and Prof. Busk. The work was commenced in July 1858, and completed in the summer of 1859.204

The cave consists of three principal galleries, with diverging232 passages, running in the direction of the joints233 from north to south, and from east to west, communicating with the surface at four points. The following is the general section (Fig. 95) of the deposits in descending234 order.

320 (A.) On the floor was a layer of stalagmite, varying from a few inches to upwards of a foot in thickness, and containing only twenty-five bones, among which were the humerus of a bear, and the antler of a reindeer.

Fig. 95.—Diagram of Deposits in Brixham Cave. (Pengelly.)

(B.) Reddish cave-earth with fragments and blocks of limestone, and of stalagmite, generally averaging from two to four feet. In it 1,102 bones were discovered irregularly scattered through its mass, and belonging to mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, lion, cave, grizzly, and brown bears, reindeer, and others. They varied235 in state of preservation, and some were scored and marked by teeth. Associated with these, thirty-six rude flint implements were met with, of indisputable human workmanship, and of the same general order as those figured by the Rev. J. MacEnery from Kent’s Hole. Among them was one lanceolate implement with rounded point and unworked butt236 end, considered by Mr. John Evans, F.R.S., of the type of those usually found in the valley gravels.205 There was, therefore, the most conclusive237 evidence that man inhabited the neighbourhood,321 either before or during the time of the accumulation of B, and before those physical changes took place by which the red silt ceased to be deposited, or the stalagmite above began to be formed.

(C.) At the bottom of the cave-earth was a deposit of gravel, principally of rounded pebbles and devoid238 of fossils.

The early history of the cave, as shown by these deposits, is given by Mr. Prestwich, in the report presented to the Royal Society, as follows:—