The Caves of Paviland.—Engis.—Trou du Frontal.—Gendron.—Neanderthal.—Gailenreuth.—Aurignac.—Bruniquel.—Cro-Magnon.— Lombrive.—Cavillon, near Mentone.—Grotta dei Colombi in Island of Palmaria, inhabited by Cannibals.—General Conclusions.

There are many prehistoric3 caves in Britain and on the Continent which do not contain remains sufficiently4 characteristic to fix the date of their use, either for occupation or burial, unless the term neolithic5 be understood to cover the wide interval6 between the pal2?olithic stage of the pleistocene on the one hand, and the bronze age on the other.

The Paviland Cave.

The Cave of Goat’s Hole155 at Paviland, in Glamorganshire, explored by Dr. Buckland in 1823, offers an instance of an interment having been made in a pre-existent deposit of the pleistocene age. It consists of a chamber7 facing to the sea, in a cliff of limestone8 100 feet high, at a level of from 30 to 40 feet above the high-water mark. Its floor was composed of red loam9, containing the remains of the woolly-rhinoceros10, hy?na, cave-bear,233 and mammoth11. Close to a skull12 with tusks14 of the last animal a human skeleton (equalling in size the largest male skeleton in the Oxford15 Museum) was discovered; and in the soil, “which had apparently16 been disturbed by ancient diggings,” were fragments of charcoal17, a small chipped flint, and the sea-shells of the neighbouring shore. Certain small ivory ornaments18, found close to the skeleton, are considered by Dr. Buckland to have been carved out of the tusks of the mammoth near which they rested; and he justly remarks that, “as they must have been cut to their present shape at a time when the ivory was hard, and not crumbling19 to pieces, as it is at present at the slightest touch, we may from this circumstance assume for them a high antiquity20.”

May we not also infer, from the fact of the manufactured ivory and the tusks from which it was cut being in precisely21 the same state of decomposition22, that the tusks were preserved from decay, during the pleistocene times, by precisely the same agency as those now found perfect in the polar regions—namely, the intense cold; that after the skull of the mammoth had been buried in the cave, the tusks, thus preserved, were used for the manufacture of ornaments; and that, at some time subsequent to the interment of the ornaments with the corpse23, a climatal change has taken place, by which the temperature in England, France, and Germany has been raised, and the ivory became decomposed24 that up to that time had preserved its gelatine? On this point it is worthy25 of remark that fossil tusks have been discovered in Scotland sufficiently perfect to be used as ivory. The ornaments may, however, not have been made from the fossil tusks.

234 The presence of the bones of sheep underneath26 the remains of mammoth, bear, and other animals, coupled with the state of the cave earth, which had been disturbed before Dr. Buckland’s examination of the cave, would prove that the interment is not of pleistocene date. No traces of sheep or goat have as yet been afforded by any pleistocene deposit in Britain, France, or Germany.

Dr. Buckland’s conclusion, that the interment is relatively27 more modern than the accumulation with remains of the extinct mammalia, must be accepted as the true interpretation28 of the facts. The intimate association of the two sets of remains, of widely diverse ages, in this cave show that extreme care is necessary in cave exploration.

The Cave of Engis.

Human remains have been obtained from some of the caves of Belgium under circumstances which are generally considered to indicate that they are of the same antiquity as the skeletons of the animals with which they are associated. The possibility, however, of the contents of caves of different ages being mixed by the action of water, or by the burrowing29 of animals, or by subsequent interments, renders such an association of little value, unless the evidence be very decided30. The famous human skull discovered by Dr. Schmerling156 in the cave of Engis, near Liége, in 1833, is a case in point. It was obtained from a mass of breccia, along with bones and teeth of mammoth, rhinoceros, horse, hy?na, and bear; and subsequently235 M. Dupont157 found in the same spot a human ulna, other human bones, worked flints, and a small fragment of coarse earthenware31. The discovery of this last is an argument in favour of the human remains being of a later date than the extinct mammalia, since pottery32 has not yet been proved to have been known to the pal?olithic races who co-existed with them, while it is very abundant in neolithic burial-places and tombs. The fact of all the objects being cemented together by calcareous infiltration33 is no test of relative age, which cannot be ascertained34 without distinct stratification, such as that in the caves of Wookey and Kent’s Hole.

It seems therefore to me, that the conditions of the discovery are too doubtful to admit of the conclusion of Sir Charles Lyell and other eminent35 writers, that the human remains are of pal?olithic age.

The skull is described by Professor Huxley158 as being of average size, its contour agreeing equally well with some Australian and European skulls36; it presents no marks of degradation37, “and is in fact a fair average human skull, which might have belonged to a philosopher, or might have contained the thoughtless brains of a savage38.” Its measurements fall within the limits of the long-skulls described in the preceding chapter, and it certainly belongs to the same class.

236 The following Table will show the variation in size and form of the skulls mentioned in this chapter:

Measurements of Skulls of doubtful antiquity.

Length. Breadth. Height. Circum-

ference. Cephalic

index. Altitudinal

index.

Engis (Huxley) ?7·7? 5·4? — 20·5? ·700 —

Trou du Fronta (Pruner-Bey) ?6·9? 5·6? — 21·55 ·811 ·704

Gailenreuth (Dawkins) ?6·82 5·5? — 21·55 ·813 ·813

Neanderthal (Schaaffhausen) 12·0 5·75 — 23·?? ·720 —

Cro-Magnon, No. 1 (Broca) 7·95 5·86 — 22·36 ·730 —

” ” 2 ” 7·52 5·39 — 21·26 ·71? —

” ” 3 ” 7·94 5·94 — 22·24 ·74? —

Trou du Frontal.

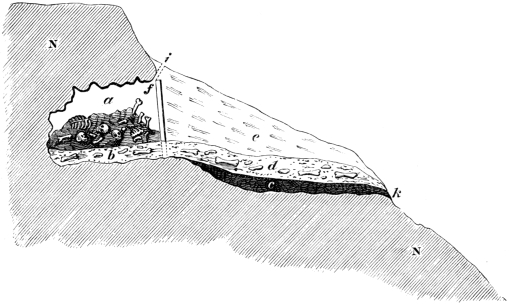

The human skeletons in the Trou du Frontal, situated39 in a picturesque40 limestone cliff on the banks of the Lesse, near Furfooz, are considered by M. Dupont to be of the same age as the contents of the caves close by the Trou des Nutons and Trou Rosette, which have been inhabited by pal?olithic savages41. The following is the section (Fig42. 69) which he gives of the deposits. Close to the river Lesse is the alluvium (No. 1), below which is a clay (No. 2), with angular blocks passing upwards43 under the rock shelter, and filling the cave. Under this is a stratum44 of loam (No. 3), resting on gravel45 (No. 4). Sixteen human skeletons were discovered in the sepulchral46 cavity (S), at the mouth of which was a large slab47 of rock (D), by which it was originally blocked up. A singular urn48, with a round bottom and with the handles perforated for suspension, was found at the entrance, together with flint flakes50, ornaments in fluorine, and eocene shells perforated for237 suspension. Outside, at the points H H, was an accumulation of broken bones, belonging to the lemming, tailless hare (Lagomys), beaver51, wild cat, boar, horse, stag, urus, chamois, goat, and other animals, birds and fishes. From the occurrence of fragments belonging to two reindeer52, it is considered by M. Dupont to belong to the reindeer age. The old hearth53 was close by, at F (Fig. 69).

Fig. 69.—Section of the Trou du Frontal. (Dupont.)

From this section we may infer, that the rock-shelter was used by man at the points H H and F before the formation of the stratum No. 2, which is probably merely subaerial rain-wash, due to the disintegration55 of the adjacent rocks, and that the sepulchral cavity was a place of burial either before, or while No. 2 was accumulated. Can we further conclude that there is any necessary connection between the refuse-heap and the sepulchre in point of time? M. Dupont holds that the contents of all the caves in the cliff are pal?olithic, and238 that the sepulchral cavity is therefore of that age.159 It seems to me, however, that the evidence in favour of this view is not conclusive56. The burial place may have belonged to one people, and the refuse-heaps in the neighbouring caves and outside the slab in the rock-shelter of the Trou du Frontal to another. The form of the urn is remarkably57 like some of those which have been obtained from the neolithic pile-dwellings of Switzerland, and therefore may possibly imply that the interment is of that age.

The human remains were mixed pêle mêle with stones and yellow clay within the chamber. Two skulls, sufficiently perfect to allow of measurement, show that their possessors were broad-headed (brachy-cephalic), and of the same type as those of Sclaigneaux. They are considered by the late Dr. Pruner-Bey to belong to the “type Mongoloide,” and are believed by M. Dupont to prove that the pal?olithic inhabitants of Belgium were a Mongoloid race. They seem, however, to be of the same general order as the broad-skulls from the neolithic caves and tombs of France, and from the round barrows of Great Britain, as well as those from the neolithic tombs of Borreby and Mo?n in Scandinavia. And they are looked upon by MM. de Quatrefages, Virchow, and Lagneaux,160 as presenting the same type as that which is to be recognized in the present population of Belgium, in the neighbourhood, for example, of Antwerp.

These affinities58 may be explained by the view advanced by Dr. Thurnam, that the broad-heads of the British, French, and Scandinavian tombs are cognate239 with the modern Fin59; or by the higher generalisation of Prof. Huxley, that the Swiss “Dissentis” skull, the South German, the Sclavonian, and the Finnish, belong to one great race of fair-haired, broad-headed, Xanthochroi “who have extended across Europe from Britain to Sarmatia, and we know not how much further to the east and south.”161

Besides these broad crania, M. Lagneaux162 calls attention to a fragment, sufficiently perfect to indicate a skull of the long type (très dolicho-céphale), and that differed from them in many other particulars. In the Trou du Frontal, therefore, there is proof that a long and a short-headed race lived in Belgium side by side, just as a similar association in the cave of Orrouy establishes the same conclusion as to the neolithic dwellers61 in France. And since skulls of both these types have been discovered in the neolithic caves of Sclaigneaux and Chauvaux, the interment in the Trou du Frontal may probably be referred to that date.

The Cave of Gendron.

The sepulchral cave of Gendron163 on the Lesse, in which fourteen skeletons were discovered lying at full length, and in regular order, along with one flake49 and some fragments of pottery, is of uncertain age, since those articles were found at the entrance, and have no necessary connection with the interments. And if they were deposited at the same time, M. Dupont’s view that they stamp the neolithic age is rendered untenable by240 the fact that flakes and rude pottery were in use as late as the date of the Roman conquest of Britain, and are frequently met with in association with articles of bronze and of iron. And for the same reasons the neolithic age of the human bones in the Trou de Sureau and of the Trou de Pont-à-Lesse is open to considerable doubt. The contents, however, prove these caves to be post-pleistocene.

Cave of Gailenreuth.

The same uncertainty62 overhangs the age of the interments in the cave of Gailenreuth, in Franconia, from which Dr. Buckland164 obtained a human skull of the same broad type as that from Sclaigneaux, along with fragments of black coarse pottery, one of which is ornamented63 with a line of finger-impressions. The skull is remarkable64 for the great width of the parietal protuberances, and the flattening65 of the upper and posterior region of the parietal bone. Its measurements are given in the Table, p. 236, from which it will be seen that it belongs to the same class of skulls as those from the neolithic caves and tumuli of France.

Cave of Neanderthal.

The extraordinary skull found in 1857 in the cave of Neanderthal,165 by Dr. Fuhlrott, with some of the other bones of the skeleton, was not associated with any other241 animals from which its age could be inferred. “Under whatever aspect,” writes Professor Huxley, “we view this cranium, whether we regard its vertical66 depression, the enormous thickness of its supraciliary ridges67, its sloping occiput, or its long and straight squamosal suture, we meet with ape-like characters, stamping it as the most pithecoid of human crania yet discovered. But Prof. Schaaffhausen states that the cranium, in its present condition, holds 1033·24 cubic centimetres of water, or about 63 cubic inches, and as the entire skull could hardly have held less than an additional 12 cubic inches, its capacity may be estimated at about 75 cubic inches, which is the average capacity given by Morton for Polynesian and Hottentot skulls.

So large a mass of brain as this would alone suggest that the pithecoid tendencies, indicated by this skull, did not extend deep into the organization, and this conclusion is borne out by the dimensions of the other bones of the skeleton, given by Prof. Schaaffhausen, which show that the absolute height and relative proportions of the limbs were quite those of a European of middle stature68. The bones are indeed stouter69, but this, and the great development of the muscular ridges noted70 by Dr. Schaaffhausen, are characters to be expected in savages. The Patagonians, exposed without shelter or protection to a climate possibly not very dissimilar from that of Europe at the time during which the Neanderthal man lived, are remarkable for the stoutness71 of their limb-bones.

In no sense, then, can the Neanderthal bones be regarded as the remains of a human being intermediate between men and apes; at most they demonstrate the existence of a man whose skull may be said to revert242 somewhat towards the pithecoid type—just as a carrier, or a poulter, or a tumbler may sometimes put on the plumage of its primitive73 stock, the Columba livia.”

This skull, like the preceding, belongs to the dolicho-cephalic division, reaching the enormous length of twelve inches, with a parietal breadth of 5·75.

A long-skull found near Ledbury Hill in Derbyshire, and belonging to the river-bed type of Prof. Huxley, comes so close to this one of Neanderthal, that were it flattened74 a little and elongated75, and possessed76 of larger supraciliary ridges, it would be converted into the nearest likeness77 which has yet been discovered.166

The Caves of France.—Aurignac.

In the cave of Neanderthal, the question of the antiquity of the human remains is not complicated by the juxtaposition78 of extinct pleistocene animals or of pal?olithic implements80. Those caves, however, in France which claim especial attention, Aurignac, Bruniquel, and Cro-Magnon, are equally famous for their interments, and the pal?olithic implements which they have furnished, along with the remains of the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, and other extinct animals.

They have both been inhabited by pal?olithic man, and been used some time for burial. Does the period of habitation coincide with that of the burial? This important question has been answered almost universally in the affirmative, and the interments are viewed as evidence of a belief in the supra-natural among the most ancient inhabitants of Europe, as well as offering examples of their physique.

243 The famous cave of Aurignac, near the town of that name, in the department of the Haute Garonne, was explored and described by the late M. Ed. Lartet, and his conclusions were adopted by Sir Charles Lyell in the first three editions of the “Antiquity of Man.” In the fourth edition,167 however, the latter author, after a reconsideration of all the circumstances, qualifies his acceptance of the pal?olithic age of the interments, and shares the doubts which have been expressed by Sir John Lubbock and Mr. John Evans. The evidence is as follows:—

M. Lartet’s account falls naturally into two parts: first, the story which he was told by the original discoverer of the cave; and, secondly81, that in which the results of his own discoveries are described. We will begin with the first. In the year 1852, a labourer, named Bonnemaison, employed in mending the roads, put his hand into a rabbit-hole (Fig. 70, f), and drew out a human bone, and having his curiosity excited, he dug down until, as his story goes, he came to a great slab of rock. Having removed this, he discovered on the other side a cavity seven or eight feet in height, ten in width, and seven in depth, almost full of human bones, which Dr. Amiel, the Mayor of Aurignac, who was a surgeon, believed to represent at least seventeen individuals. All these human remains were collected, and finally committed to the parish cemetery82, where they rest to the present day, undisturbed by sacrilegious hands. Fortunately, however, Bonnemaison in digging his way into the grotto83, had met with the remains of extinct animals, and works of art; and these were244 preserved until, in 1860, M. Lartet accidentally heard of the discovery, and investigated the circumstances on the spot. He found that Bonnemaison, and the sexton who had buried the human remains, had taken so little note of the place where they were interred84, that it could not be identified, and on examining the cave he found that the interior had been ransacked85, and the original stratification to a great extent disturbed. M. Lartet’s exploration showed that a stratum containing the remains of the cave-bear, lion, rhinoceros, hy?na, mammoth, bison, horse, and other animals, and pal?olithic implements, like those of Périgord, extended from the plateau (d) outside into (b) the cave. On the outside he met with ashes, and burnt and split bones, which proved that it had been used as a feasting-place by the pal?olithic hunters; within he detected no traces of charcoal, and no traces of the hy?nas, which were abundant outside. Inside he met with a few human bones in the earth which Bonnemaison had disturbed, which were in the same mineral condition as those of the extinct animals, and he, therefore, inferred that they were of the same age. Such is the summary of the facts which M. Lartet discovered. He has, of his own personal knowledge, only proved that Aurignac was occupied by a tribe of hunters during the pal?olithic age, and that it had been used as a burial-place.

Fig. 70.—Diagram of the Cave of Aurignac.

Is he further justified87 in concluding that the period of pal?olithic occupation coincides with that in which the burial took place? Bonnemaison’s recollections may be estimated at their proper value by the significant fact, that, in the short space of eight years intervening between the discovery and the exploration, he had forgotten where the skeletons had been buried. And245 even if his account be true in the minutest detail, it does not afford a shadow of evidence in favour of the cave having been a place of sepulchre in pal?olithic times, but merely that it had been so used at some time or another. If we turn to the diagram constructed by M. Lartet to illustrate88 his views (“Ann. des Sc. Nat. Zool.,” 4e sér., t. xv., pl. 10), and made for the most part from Bonnemaison’s recollections; or to the amended89 diagram (Fig. 70) given by Sir Charles Lyell (“Antiquity of Man,” 1st ed., Fig. 25), we shall see that the skeletons are depicted90 above the stratum (b) containing the pal?olithic implements and pleistocene mammalia; and therefore, according to the laws of geological evidence, they must have been buried after the subjacent deposit was accumulated. The previous disturbance91 of the cave-earth does away with the conclusion, that the few human bones found by M. Lartet are of the same age as the extinct mammalia in the deposit. The absence of charcoal inside was quite as likely to be246 due to the fact that a fire kindled92 inside would fill the grotto with smoke, while outside the pal?olithic savage could feast in comfort, as to the view that the ashes are those of funereal93 feasts in honour of the dead within, held after the slab had been placed at the entrance. The absence of the remains of hy?nas from the interior is also negative evidence, disproved by subsequent examination.

The researches of the Rev72. S. W. King, in 1865, complete the case against the current view of the pal?olithic character of the interments, since they show that M. Lartet did not fully94 explore the cave, and that he consequently wrote without being in possession of all the facts. The entrance was blocked up, according to Bonnemaison, by a slab of stone, which, if the measurements of the entrance be correct, must have been at least nine feet long and seven feet high, placed, according to M. Lartet, to keep the hy?nas from the corpses95 of the dead. It need hardly be remarked, that the access of these bone-eating animals to the cave would be altogether incompatible96 with the preservation97 of the human skeletons, had they been buried at the same time. The enormous slab was never seen by M. Lartet, and it did not keep out the hy?nas. In the collection made by the Rev. S. W. King from the interior there are two hy?nas’ teeth, and nearly all the antlers and bones bear the traces of the gnawing98 of these animals. The cave, moreover, has two entrances instead of one, as M. Lartet supposed when his paper in the “Annales” was published. The bones of the sheep, or goat, also obtained from the inside, and preserved in the Christy Museum, afford strong evidence that the interment is not pal?olithic; and a fragment of pottery, agreeing exactly with that247 used in the neolithic age, probably indicates its relative antiquity. This conclusion has also been arrived at by the two most recent explorers, MM. Cartaillac and Gautier.

The skeletons, therefore, in the Aurignac cave cannot be taken to be of the same age as the stratum on which they rested; but, so far as there is any evidence, may probably be referred to the neolithic age, in which the custom of burial in caves prevailed throughout Europe.

Cavern99 of Bruniquel.

The famous cavern of Bruniquel, explored by the Vicomte de Lastic in 1863–4,168 and described by Professor Owen, is also one of the class which has furnished human bones, along with the remains of the extinct mammalia. It penetrates100 a cliff in the Jurassic limestone, opposite the little village of Bruniquel (Tarn and Garonne), about forty feet above the level of the river Aveyron. The bottom was covered with a sheet of stalagmite, resting on earth and blocks of stone, for the most part finely cemented into a breccia, that is black with the particles of carbon constituting the “limon noir” of the workmen, four or five feet thick, beneath which is the “limon rouge,” or red earth without charcoal, from three to four feet thick. Every part of the breccia is charged with the broken remains of the wolf, rhinoceros, horse, reindeer, stag, Irish elk101 and bison, and pal?olithic implements of flint and bone; some of the latter having well-executed designs of the heads of horses and reindeer, which prove that the cave had been used as a place of habitation by the hunters of those animals. Imbedded in the breccia at a depth of from three to five feet human bones were met248 with, and in two recesses102 several individuals, including a child, were found, one of which Professor Owen and the Vicomte de Lastic disinterred with sufficient care to prove that the body had been buried in the crouching103 posture104. The only calvarium sufficiently perfect to allow of a comparison belonged to the dolicho-cephalic type, and was very fairly developed.

Professor Owen infers, from the intimate association of the human bones with the pal?olithic implements and mammalia, that the cave of Bruniquel was used as a burial-place by the same people who had used it for habitation, and advances, in support of this, that the bones of man and of the animals are exactly in the same state of preservation, having lost the same amount of gelatine. The evidence, however, does not seem to be altogether conclusive. If the interment had been made after the pal?olithic inhabitants had forsaken105 the cave, the association of the human bones with the refuse bones in their old refuse-heap must inevitably106 have taken place. And if, further, water charged with carbonate of lime percolated107 the mass, it would be converted into a hard breccia, and ultimately covered with a sheet of stalagmite. This calcification108 may have taken place in modern times. A modern bone, as Mr. Evans has observed in the case of Aurignac, may lose its gelatine in a comparatively short time, and become chemically identical with those which have been imbedded in the same matrix for long ages. The mineral condition, therefore, is an uncertain test of relative antiquity.

For these reasons it seems to be doubtful whether the interment is of the same age as the occupation. The skull-shape, and the burial in the crouching posture,249 point rather in the direction of the long-headed race, that buried their dead in caves, in the neolithic age, in France, Spain, Belgium, and Great Britain.

The Cave of Cro-Magnon.

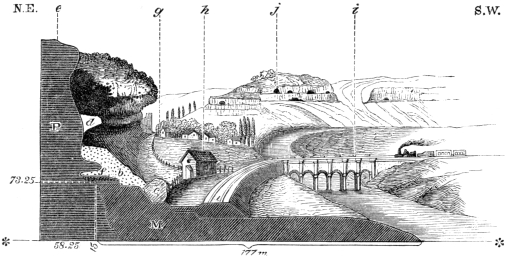

The human skeletons in the cave of Cro-Magnon, at Les Eyzies, a little village on the banks of the Vezère in Périgord, fall into the same doubtful category as those of Aurignac. The cave (Fig. 71, f), situated at the base of a low cliff, was completely concealed109 by a talus of loose débris, four metres thick, which had fallen from above. (Fig. 71, b.)

Fig. 71.—Section across the Valley of the Vezère, and through the rock of Cro-Magnon.

Level of the Vezère at low water, 58·25 metres above the sea.

Height of cave above the Vezère, 15 metres; above the sea-level, 73·25 metres.

Distance from the cave to the river, 177 metres.

a Railroad.

b Talus.

c Great block of stone.

d Ledge86 of rock.

P Limestone.

M Detritus111 of the slopes and alluvium of the Valley.

e Rock of Cro-Magnon.

f Cave.

g Chateau112 and Village of Les Eyzies, in the Valley of the Beaune.

h Gatekeeper’s house.

i Railway bridge over the Vezère.

j Caves of Le Cingle.

It forms one of a group of caves at various heights above the Vezère, which are very well represented in250 the preceding figure, which I am kindly113 allowed to borrow from the “Reliqui? Aquitanic?” (Fig. 39).

At the time of its discovery in 1868, in the course of making an embankment for the railway close by, and of obtaining material for mending the roads, it was completely blocked up. On the removal of this (b), by the contractors114 MM. Bertoú-Meyroú and Delmarés, the entrance was exposed, and human remains and worked flints revealed, which were carefully exhumed115 in the presence of MM. Laganne, Galy, and Simon. At this stage of the exploration M. Louis Lartet was deputed, by the Minister of Public Instruction, to superintend the work, and from his report the following account is taken (Lartet and Christy, “Rel. Aq.,” p. 66) by the courtesy of the editors.

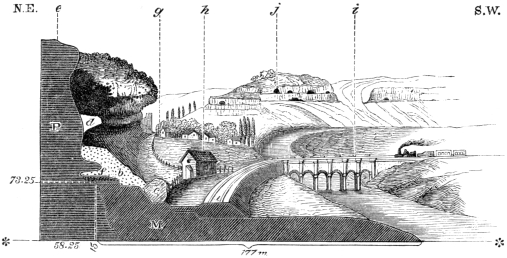

“The cave of Cro-Magnon is formed by a projecting ledge of cretaceous limestone (rich with fossil corals and polyzoans), having a thickness of 8 metres and a length of 17 metres (Fig. 72, P). The bed which it overlies, and the destruction of which has given rise to the cave, abounds116 with Rhynchonella vespertilio, which is a type fossil, fixing the geological horizon. The débris of this marly and micaceous117 limestone had accumulated on the original floor of the cavern to a great thickness, at least for 0·70 metres (see Fig. 72, A), when the hunters of the reindeer stopped here for the first time, leaving as a trace of their short stay a blackish layer (Fig. 72, B), from 0·05 to 0·15 metre thick, containing worked flints, bits of charcoal, broken or calcined bones, and in its upper portion the elephant tusk13 before alluded118 to (Fig. 72, a).

Fig. 72.—Detailed Section of the Cave of Cro-Magnon, near Les Eyzies.

Scale = 1/100 (1 centimetre to 1 metre).

A Débris of soft limestone.

B First layer of ashes, &c.

C Calcareous débris.

D Second layer of ashes, &c.

E Calcareous débris, reddened by fire under the next layer of ashes, &c.

F Third layer of ashes, &c.

G Red earth, with bones, &c.

H Thickest layer of ashes, bones, &c.

I Yellowish earth, with bones, flints, &c.

J Thin bed of hearth-stuff.

K Calcareous débris.

L Rubbish of the Talus.

N Crack in the projecting ledge of rock.

P Projecting shelf of hard limestone.

Y Place of the pillar made to support the roof.

a Tusk of an elephant.

b Bones of an old man.

c Block of gneiss.

d Human bones.

e Slabs119 of stone fallen from the roof at different times.

“This first hearth is covered by a layer (C), 0·25 metre thick, of calcareous débris, detached bit by bit from the251 roof, during the temporary disuse of the shelter. Then follows another thin layer of hearth-stuff (D), 0·10 metre thick, also containing pieces of charcoal, bones, and worked flints. This bed is in its turn overlain by a layer of fallen limestone rubbish (E), 0·50 metre thick. Lastly, there is over these a series of more important layers, all of them containing, in different proportions,252 charcoal, bones (broken, burnt, and worked), worked flints (of different types, but chiefly scrapers), flint cores, and pebbles120 of quartz121, granites122, &c. from the bed of the Vezère, and bearing numerous marks of hammering. Altogether these layers seem to have reference to a period during which the cave was inhabited, if not continuously, at least at intervals123 so short as not to admit of intercalations of débris falling from the roof between the different hearth-layers which correspond with the successive phases of this (the third) period of habitation. The first (lowest) of these layers (F) is full of charcoal, and has a thickness of 0·20 metre; it does not touch the back of the cave, but extends a little further than the earlier layers. At its line of contact with the calcareous débris beneath, the latter is strongly reddened with the action of fire.

“On the last-mentioned hearth-layer is a bed of unctuous124 reddish earth (G), 0·30 metre thick, containing similar objects, though in less quantities. Last in succession is a carbonaceous bed (H), the widest and thickest of all, having an average thickness of 0·30 metre; at the edges it is only 0·10 metre thick; but in the centre, where it cuts into the subjacent deposits, which were excavated125 by the inhabitants in making the principal hearth, it attains126 a depth of 1·60 metre. This bed, being by far the richest in pieces of charcoal, in bones, pebbles of quartz, worked flints, flint cores, and bone implements, such as points or dart-heads, arrowheads, &c., may be regarded as indicative of a far more prolonged habitation than the previous.

“Above this thick hearth-layer is a bed of yellowish earth (I), rather argillaceous, also containing bones, flints, and implements of bone, as well as amulets127 or pendants.253 This appears to be limited upwards by a carbonaceous bed (J), very thin, and of little extent, 0·05 metre thick, which M. Laganne observed before my arrival, but of which only slight traces remained afterwards.

“It was on the upper part of this yellow band (I), and at the back of the cave, that the human skeletons and the accessories of the sepulture were met with; and all of them were found in the calcareous débris (K), except in a small space in the furthest hollow at the back of the cave. This last deposit also contains some worked flints, mixed up with broken bones, and with some uninjured bones referable to small rodents129 and to a peculiar130 kind of fox.

“Lastly, above these different layers, and all over the shelter itself, lay the rubbish of the talus (four to six metres thick), sufficient in itself, according to what we have said above about its mode of formation, to carry back the date of the sepulture to a very distant period in the prehistoric age.

“As for the human remains, and the position they occupied in bed I, the following are the results of my careful inquiries131 in the matter. At the back of the cave was found an old man’s skull (b), which alone was on a level with the surface, in the cavity not filled up in the back of the cave, and was therefore exposed to the calcareous drip from the roof, as is shown by its having a stalagmitic coating on some parts. The other human bones, referable to four other skeletons, were found around the first, within a radius132 of about 1·50 metre. Among these bones were found, on the left of the old man, the skeleton of a woman, whose skull presents in front a deep wound, made by a cutting instrument, but which did not kill her at once, as the bone has been254 partly repaired within; indeed our physicians think that she survived several weeks. By the side of the woman’s skeleton was that of an infant which had not arrived at its full time of f?tal development. The other skeletons (Fig. 70, d) seem to have been those of men.

“Amidst the human remains lay a multitude of marine133 shells (about 300), each pierced with a hole, and nearly all belonging to the species Littorina littorea so common on our Atlantic coasts. Some other species, such as Purpura lapillus, Turritella communis, &c., occur, but in small numbers. These are also perforated, and, like the others, have been used for necklaces, bracelets134, or other ornamental135 attire136. Not far from the skeletons, I found a pendant or amulet128 of ivory, oval, flat, and pierced with two holes. M. Laganne had already discovered a smaller specimen137; and M. Ch. Grenier, schoolmaster at Les Eyzies, has kindly given me another, quite similar, which he had received from one of his pupils. There were also found near the skeletons several perforated teeth, a large block of gneiss, split and presenting a large smoothed surface; also worked antlers of reindeer, and chipped flints, of the same types as those found in the hearth-layers underneath.

“... The presence, at all levels, of the same kind of flint scrapers, as finely chipped as those of the Gorge138 d’Enfer, and of the same animals as in that classic station, evidently shows them to be relics139 of the successive habitation of the Cro-Magnon shelter by the same race of nomadic140 hunters, who at first could use it merely as a rendezvous141, where they came to share the spoils of the chase taken in the neighbourhood; but coming again, they made a more permanent occupation,255 until their accumulated refuse and the débris gradually raised the floor of the cave, leaving the inconvenient142 height of only 1·20 metre between it and the roof; and then they abandoned it by degrees, returning once more at last to conceal110 their dead there. No longer accessible, except perhaps to the foxes above noticed, this shelter, and its strange sepulture, were slowly and completely hidden from sight by atmospheric143 degradation bringing down the earthy covering, which, by its thickness, alone proves the great antiquity of the burial in the cave.”

These conclusions as to the age of the burial do not seem to me to be supported by the facts of the case. That the cave was inhabited by a tribe of pal?olithic hunters there can be no doubt, but no evidence has been brought forward that it was used by them for the burial of their dead. They “abandoned it by degrees,” but what proof is there that they “returned once more to conceal their dead”? The interments are at a higher horizon than the strata144 of occupation, and therefore later, and although pal?olithic implements have been found “near” them, the value of the latter, in indicating the date, is destroyed by their occurrence throughout the old floors below. If we suppose that long after the cave had been inhabited by the hunters of the reindeer, it was chosen by a family as a burial-place, all the conditions of the discovery will be satisfied. The pre-existent strata would be disturbed in the process of burial, and the burrowing of foxes, and possibly of rabbits, might bring the pal?olithic implements into close association with the human bones. Taking the whole evidence into account, I should feel inclined to assign the interment to the neolithic age, in which cave-burial was so common; but whatever256 view be held, the facts do not warrant the human skeletons being taken as proving the physique of the pal?olithic hunters of the Dordogne, or as a basis for an inquiry145 into the ethnology of the pal?olithic races.

The largest cranium (see Table, p. 236), belonging to an old man, had the frontal region well developed, is orthognathic, with upturned nasals, and dolicho-cephalic. The occipital protuberance, or probole, is small. The bones of the extremity147 imply a stature of not less than five foot eleven inches for the man; the femur is carinate, and the tibi? platycnemic (see Fig. 48).

The Cave of Lombrive.

The human bones, obtained by MM. Garrigou, Filhol, and Rames, from the cave of Lombrive169 in the Department of Ariège, are, equally with those cited above, of doubtful antiquity. They were discovered on the superficial sandy loam, passing in places into a calcareous breccia, which rests at various levels in the chambers148, passages, and fissures149, along with bones of the brown-bear, urus, small ox, reindeer, stag, horse, and dog. From the occurrence of the reindeer the deposit is assigned to the pal?olithic age. But since this animal has been proved to have been eaten in Scotland by the neolithic men of Caithness, and to have inhabited Britain in the prehistoric age, it is by no means improbable that it may also have lived in the region of the Pyrenees in post-pleistocene times. The presence of the dog and the small domestic ox (Bos longifrons?) fixes the date of the accumulation as not being earlier than prehistoric;257 for both those animals were introduced into Europe by neolithic peoples.

The two human skulls, described by Professor Vogt, from this deposit confirm this conclusion, since they are of the broad type, and differ in no important character (Thurnam) from those of the neolithic brachy-cephali of France and Belgium.

The Cave of Cavillon, near Mentone.

The cave of Cavillon, explored by M. Rivière, in 1872, in the neighbourhood of Mentone, a few hundred yards on the Italian side of the frontier of France, is another case of the occurrence of human remains in association with those of the extinct animals. The floor is composed of dark earth, full of charcoal and fragments of bones, mingled150 with blocks of stone which have dropped from the roof. Below it, at a depth of six and a half metres, a skeleton was met with, as well as flint-flakes, rude instruments of bone, and a number of shells perforated for suspension. The skull was covered with a head-dress of more than 200 perforated sea-shells. It rested in an attitude of repose151, with the legs and arms bent,170 as may be seen in the admirable photo-lithograph given by M. Rivière in the volume of the “International Congress of Prehistoric Arch?ology,” published at Brussels, pl. 6. The teeth and bones of hy?na, lion, woolly rhinoceros, mammoth, and other pleistocene animals occurred both in the soil above and below, and for that reason both the discoverer and Sir Charles Lyell believe that the interment dates back to the time when those animals were258 living. If, however, neolithic savages, or those of a later age, had buried the skeleton in the earth containing the extinct animals, all the circumstances which have been noticed, either by Mr. Pengelly or Mr. Moggridge,171 may be satisfactorily explained. There are no stalagmites to divide one stratum from another, and were an interment made in the cave at the present time, the discoverer two or three centuries hence might assert, with equal justice, that it took place in the pleistocene age, because of the association with the animals characteristic of that remote period.

The superficial portions of the cave-earth had certainly been disturbed, and there is no evidence that the disturbance did not extend down to the horizon where the skeleton rested. Nevertheless, Mr. Pengelly concludes that the interment is of pal?olithic age from its analogy with that of Cro-Magnon and Paviland, which we have seen to be of equally doubtful antiquity. It seems to me that this conclusion, which is almost universally accepted, is not warranted by the facts, and that it cannot be used in support of any speculation152 as to the condition of man in the pleistocene age.

The skull is described by M. Rivière as long, the thigh-bones are strongly carinate, and the tibi? are platycnemic as in the case of those from Cro-Magnon, Gibraltar, Sclaigneaux, and North Wales.

Grotta dei Colombi in Island of Palmaria, inhabited by Cannibals.

We are indebted to Professor Capellini for an account of the exploration of the Grotta dei Colombi, a cave in a259 vertical cliff in the island of Palmaria,172 overlooking to the south the Gulf153 of Spezzia. In the red loam, composing the floor, were numerous flakes and scrapers, a rounded “striker” of Saussurite, quartz, pebbles, fragments of pottery, a bone needle, a whistle made of the first phalange of a goat’s foot, shells perforated for suspension, Natica mille-punctata, Pectunculus glycimeris, and Patella c?rulea, together with bones of goat, hog146, ox, wolf, wild cat, and broken and cut human bones belonging to children and young adults.

Among the remains Professor Capellini draws attention in particular to the thigh-bones, scorched154 by fire, one of which bears incisions155 on its posterior face made by a flint implement79 in cutting away the flesh (Pl. 73, a), and is also marked by scraping. He considers that they belong to an ape, closely allied156 to the Macacus innuus of Gibraltar and North Africa, and concludes, therefore, that the animal was living in Palmaria at the time that the cave was inhabited. This identification is forbidden by the spongy texture157, the rounded contour, and the absence of epiphyses that imply that the bone was very young, and that in the adult it would be far larger than any thigh-bone of the apes. On comparing his figures with eight femora belonging to young children, from the cairn at Cefn, and the caves at Perthi-Chwareu, I find that they agree in every particular with two, the flattening of the inferior extremity, considered by Prof. Calori to be a non-human character, being equally met with in all, and being relatively greater in the younger than the older. They offer, therefore, unmistakeable proof that the inhabitants of the cave were cannibals (Fig. 73). I am informed by my friend, Prof. Busk,260 that the bone figured belonged to a child about eight years old. The outline b in the figure represents the contour of one of the femora from the cavern at Cefn, described in the fifth chapter.

Fig. 73.—Thigh-bone of child from Grotta dei Colombi (Capellini). a, Cuts; b, Outline of corresponding thigh-bone from cavern at Cefn.

In this cave, as in those quoted above, there are no polished stone implements, or works of art, that establish that these feasts were carried on in the cave by neolithic cannibals, for the rude flint-flakes and bone articles, taken by Professor Capellini to fix its date, are common both to the pal?olithic and the bronze ages. Nevertheless, since the inhabitants have left behind no trace of any metal, and since their food was wholly supplied by the existing animals, they were probably in the neolithic stage of culture, if this be taken to cover the wide interval extending from the pleistocene to the age of bronze. They are proved, by the rudeness of their implements, to have been savages of a very low order.

261 We may gather from various allusions158, and stories scattered159 through the classical writers, such for example as that of the Cyclops, that the caves on the shores of the Mediterranean160 were inhabited by cannibals in ancient times. In the island of Palmaria we meet with unmistakeable proof that it was no mere54 idle tale or poetical161 dream. But we have no proof that cannibalism162 was universally practised at any stage in the history of man. All the caves of Europe, explored up to the present time, merely afford some three or four examples in the neolithic and bronze ages. In the pleistocene there is no instance which is devoid163 of doubt. This atrocious practice is therefore to be viewed as abnormal, and it probably became ingrafted into the religious ideas of the nations of antiquity from the horror by which it was surrounded, ultimately surviving in the form of human sacrifices to the offended gods.

General Conclusions as to Prehistoric Caves.

We have seen in the fifth and sixth chapters that the prehistoric caves which are so unimportant in the ages of bronze and iron, were used in the neolithic age throughout western Europe both for habitation and burial, and that they therefore offer us most valuable materials for working out the ethnology of Europe at that remote time. The two races of men, the remains of which they contain, are represented by the modern Basque and Berber on the one hand, and on the other by the Celt, and in Russia and Germany by the cognate60 Finn, Sclave, and Wend. And since all the human remains described in the present chapter, those of Cro-Magnon and possibly of262 the Grotta dei Colombi being exempted164, belong to one of other of these types, they may be referred to the neolithic age with a high degree of probability. In the present stage of the inquiry, it is much safer to put them into a distinct class, apart from those to which we can assign a relative age with tolerable certainty.

In the long ages which elapsed between the close of the pleistocene period and the dawn of history other races than these may have occupied Europe, and have passed away without leaving any clue as to their identity. But in the present state of our knowledge we are justified only in concluding, that the oldest population in prehistoric times was non-Aryan, the traces of which are left behind not merely in the caves and tombs, but in language,173 and in the small dark-haired inhabitants of western and southern Europe.

The prehistoric peoples lived under physical conditions very different from those of central and western Europe at the present time; the surface of the country being covered with rock, forest, and morass165, which afforded shelter to the elk, bison, urus, stag, megaceros, and wild boar, as well as to innumerable wolves. They arrived from the east with cereals and domestic animals, some of which, such as the Bos longifrons and Sus palustris, reverted166 to their original wild state. From the very exigencies167 of their position they lived partly by hunting, and they gradually pushed their way westward168, carrying with them the rudiments169 of that civilization which we ourselves possess.

263 It is an open question whether they came into contact with the pal?olithic races which preceded them.

The climate which they enjoyed was sufficiently severe to allow the reindeer to inhabit the district on which now stands the city of London, and its severity may also be inferred from the thickness of the bark of the Scotch170 firs, observed by Mr. Godwin-Austen in the submarine forests of the south of England, and by Mr. James Geikie in those of Scotland. The area of Great Britain was greater then, than now, since a plain extended seawards from the coast-line, nearly everywhere, supporting a dense171 forest of Scotch fir, oak, birch, and alder172, the relics of which are to be seen in the beds of peat, and the stumps173 of the trees, near low-water mark on most of our shores. And it may be inferred that the forest extended a considerable distance from the present sea margin174, from the large size of the trunks of the trees.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

pal

|

|

| n.朋友,伙伴,同志;vi.结为友 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

prehistoric

|

|

| adj.(有记载的)历史以前的,史前的,古老的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

neolithic

|

|

| adj.新石器时代的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

interval

|

|

| n.间隔,间距;幕间休息,中场休息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

chamber

|

|

| n.房间,寝室;会议厅;议院;会所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

limestone

|

|

| n.石灰石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

loam

|

|

| n.沃土 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

rhinoceros

|

|

| n.犀牛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

mammoth

|

|

| n.长毛象;adj.长毛象似的,巨大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

skull

|

|

| n.头骨;颅骨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

tusk

|

|

| n.獠牙,长牙,象牙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

tusks

|

|

| n.(象等动物的)长牙( tusk的名词复数 );獠牙;尖形物;尖头 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

Oxford

|

|

| n.牛津(英国城市) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

apparently

|

|

| adv.显然地;表面上,似乎 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

charcoal

|

|

| n.炭,木炭,生物炭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

ornaments

|

|

| n.装饰( ornament的名词复数 );点缀;装饰品;首饰v.装饰,点缀,美化( ornament的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

crumbling

|

|

| adj.摇摇欲坠的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

antiquity

|

|

| n.古老;高龄;古物,古迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

precisely

|

|

| adv.恰好,正好,精确地,细致地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

decomposition

|

|

| n. 分解, 腐烂, 崩溃 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

corpse

|

|

| n.尸体,死尸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

decomposed

|

|

| 已分解的,已腐烂的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

worthy

|

|

| adj.(of)值得的,配得上的;有价值的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

underneath

|

|

| adj.在...下面,在...底下;adv.在下面 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

relatively

|

|

| adv.比较...地,相对地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

interpretation

|

|

| n.解释,说明,描述;艺术处理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

burrowing

|

|

| v.挖掘(洞穴),挖洞( burrow的现在分词 );翻寻 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

decided

|

|

| adj.决定了的,坚决的;明显的,明确的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

earthenware

|

|

| n.土器,陶器 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

pottery

|

|

| n.陶器,陶器场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

infiltration

|

|

| n.渗透;下渗;渗滤;入渗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

ascertained

|

|

| v.弄清,确定,查明( ascertain的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

eminent

|

|

| adj.显赫的,杰出的,有名的,优良的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

skulls

|

|

| 颅骨( skull的名词复数 ); 脑袋; 脑子; 脑瓜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

degradation

|

|

| n.降级;低落;退化;陵削;降解;衰变 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

savage

|

|

| adj.野蛮的;凶恶的,残暴的;n.未开化的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

situated

|

|

| adj.坐落在...的,处于某种境地的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

picturesque

|

|

| adj.美丽如画的,(语言)生动的,绘声绘色的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

savages

|

|

| 未开化的人,野蛮人( savage的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

upwards

|

|

| adv.向上,在更高处...以上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

stratum

|

|

| n.地层,社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

gravel

|

|

| n.砂跞;砂砾层;结石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

sepulchral

|

|

| adj.坟墓的,阴深的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

slab

|

|

| n.平板,厚的切片;v.切成厚板,以平板盖上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

urn

|

|

| n.(有座脚的)瓮;坟墓;骨灰瓮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

flake

|

|

| v.使成薄片;雪片般落下;n.薄片 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

flakes

|

|

| 小薄片( flake的名词复数 ); (尤指)碎片; 雪花; 古怪的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

beaver

|

|

| n.海狸,河狸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

reindeer

|

|

| n.驯鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

hearth

|

|

| n.壁炉炉床,壁炉地面 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

mere

|

|

| adj.纯粹的;仅仅,只不过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

disintegration

|

|

| n.分散,解体 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

conclusive

|

|

| adj.最后的,结论的;确凿的,消除怀疑的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

remarkably

|

|

| ad.不同寻常地,相当地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

affinities

|

|

| n.密切关系( affinity的名词复数 );亲近;(生性)喜爱;类同 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

fin

|

|

| n.鳍;(飞机的)安定翼 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

cognate

|

|

| adj.同类的,同源的,同族的;n.同家族的人,同源词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

dwellers

|

|

| n.居民,居住者( dweller的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

uncertainty

|

|

| n.易变,靠不住,不确知,不确定的事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

ornamented

|

|

| adj.花式字体的v.装饰,点缀,美化( ornament的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

flattening

|

|

| n. 修平 动词flatten的现在分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

vertical

|

|

| adj.垂直的,顶点的,纵向的;n.垂直物,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

ridges

|

|

| n.脊( ridge的名词复数 );山脊;脊状突起;大气层的)高压脊 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

stature

|

|

| n.(高度)水平,(高度)境界,身高,身材 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

stouter

|

|

| 粗壮的( stout的比较级 ); 结实的; 坚固的; 坚定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

noted

|

|

| adj.著名的,知名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

stoutness

|

|

| 坚固,刚毅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

rev

|

|

| v.发动机旋转,加快速度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

primitive

|

|

| adj.原始的;简单的;n.原(始)人,原始事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

flattened

|

|

| [医](水)平扁的,弄平的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

elongated

|

|

| v.延长,加长( elongate的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

possessed

|

|

| adj.疯狂的;拥有的,占有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

likeness

|

|

| n.相像,相似(之处) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

juxtaposition

|

|

| n.毗邻,并置,并列 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

implement

|

|

| n.(pl.)工具,器具;vt.实行,实施,执行 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

implements

|

|

| n.工具( implement的名词复数 );家具;手段;[法律]履行(契约等)v.实现( implement的第三人称单数 );执行;贯彻;使生效 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

secondly

|

|

| adv.第二,其次 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

cemetery

|

|

| n.坟墓,墓地,坟场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

grotto

|

|

| n.洞穴 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

interred

|

|

| v.埋,葬( inter的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

ransacked

|

|

| v.彻底搜查( ransack的过去式和过去分词 );抢劫,掠夺 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

ledge

|

|

| n.壁架,架状突出物;岩架,岩礁 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

justified

|

|

| a.正当的,有理的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

illustrate

|

|

| v.举例说明,阐明;图解,加插图 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

Amended

|

|

| adj. 修正的 动词amend的过去式和过去分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

depicted

|

|

| 描绘,描画( depict的过去式和过去分词 ); 描述 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

disturbance

|

|

| n.动乱,骚动;打扰,干扰;(身心)失调 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

kindled

|

|

| (使某物)燃烧,着火( kindle的过去式和过去分词 ); 激起(感情等); 发亮,放光 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

funereal

|

|

| adj.悲哀的;送葬的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

fully

|

|

| adv.完全地,全部地,彻底地;充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

corpses

|

|

| n.死尸,尸体( corpse的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

incompatible

|

|

| adj.不相容的,不协调的,不相配的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

preservation

|

|

| n.保护,维护,保存,保留,保持 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

gnawing

|

|

| a.痛苦的,折磨人的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

cavern

|

|

| n.洞穴,大山洞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

penetrates

|

|

| v.穿过( penetrate的第三人称单数 );刺入;了解;渗透 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

elk

|

|

| n.麋鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

recesses

|

|

| n.壁凹( recess的名词复数 );(工作或业务活动的)中止或暂停期间;学校的课间休息;某物内部的凹形空间v.把某物放在墙壁的凹处( recess的第三人称单数 );将(墙)做成凹形,在(墙)上做壁龛;休息,休会,休庭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

crouching

|

|

| v.屈膝,蹲伏( crouch的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

posture

|

|

| n.姿势,姿态,心态,态度;v.作出某种姿势 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

Forsaken

|

|

| adj. 被遗忘的, 被抛弃的 动词forsake的过去分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

inevitably

|

|

| adv.不可避免地;必然发生地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

percolated

|

|

| v.滤( percolate的过去式和过去分词 );渗透;(思想等)渗透;渗入 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

calcification

|

|

| n.钙化 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

concealed

|

|

| a.隐藏的,隐蔽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

conceal

|

|

| v.隐藏,隐瞒,隐蔽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

detritus

|

|

| n.碎石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

chateau

|

|

| n.城堡,别墅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

kindly

|

|

| adj.和蔼的,温和的,爽快的;adv.温和地,亲切地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

contractors

|

|

| n.(建筑、监造中的)承包人( contractor的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

exhumed

|

|

| v.挖出,发掘出( exhume的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

abounds

|

|

| v.大量存在,充满,富于( abound的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

micaceous

|

|

| adj.云母的,含云母的,云母状的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

alluded

|

|

| 提及,暗指( allude的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

slabs

|

|

| n.厚板,平板,厚片( slab的名词复数 );厚胶片 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

120

pebbles

|

|

| [复数]鹅卵石; 沙砾; 卵石,小圆石( pebble的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

quartz

|

|

| n.石英 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

granites

|

|

| 花岗岩,花岗石( granite的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

intervals

|

|

| n.[军事]间隔( interval的名词复数 );间隔时间;[数学]区间;(戏剧、电影或音乐会的)幕间休息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

unctuous

|

|

| adj.油腔滑调的,大胆的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

125

excavated

|

|

| v.挖掘( excavate的过去式和过去分词 );开凿;挖出;发掘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

126

attains

|

|

| (通常经过努力)实现( attain的第三人称单数 ); 达到; 获得; 达到(某年龄、水平、状况) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

127

amulets

|

|

| n.护身符( amulet的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

128

amulet

|

|

| n.护身符 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

129

rodents

|

|

| n.啮齿目动物( rodent的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

130

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

131

inquiries

|

|

| n.调查( inquiry的名词复数 );疑问;探究;打听 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

132

radius

|

|

| n.半径,半径范围;有效航程,范围,界限 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

133

marine

|

|

| adj.海的;海生的;航海的;海事的;n.水兵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

134

bracelets

|

|

| n.手镯,臂镯( bracelet的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

135

ornamental

|

|

| adj.装饰的;作装饰用的;n.装饰品;观赏植物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

136

attire

|

|

| v.穿衣,装扮[同]array;n.衣着;盛装 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

137

specimen

|

|

| n.样本,标本 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

138

gorge

|

|

| n.咽喉,胃,暴食,山峡;v.塞饱,狼吞虎咽地吃 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

139

relics

|

|

| [pl.]n.遗物,遗迹,遗产;遗体,尸骸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

140

nomadic

|

|

| adj.流浪的;游牧的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

141

rendezvous

|

|

| n.约会,约会地点,汇合点;vi.汇合,集合;vt.使汇合,使在汇合地点相遇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

142

inconvenient

|

|

| adj.不方便的,令人感到麻烦的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

143

atmospheric

|

|

| adj.大气的,空气的;大气层的;大气所引起的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

144

strata

|

|

| n.地层(复数);社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

145

inquiry

|

|

| n.打听,询问,调查,查问 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

146

hog

|

|

| n.猪;馋嘴贪吃的人;vt.把…占为己有,独占 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

147

extremity

|

|

| n.末端,尽头;尽力;终极;极度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

148

chambers

|

|

| n.房间( chamber的名词复数 );(议会的)议院;卧室;会议厅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

149

fissures

|

|

| n.狭长裂缝或裂隙( fissure的名词复数 );裂伤;分歧;分裂v.裂开( fissure的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

150

mingled

|

|

| 混合,混入( mingle的过去式和过去分词 ); 混进,与…交往[联系] | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

151

repose

|

|

| v.(使)休息;n.安息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

152

speculation

|

|

| n.思索,沉思;猜测;投机 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

153

gulf

|

|

| n.海湾;深渊,鸿沟;分歧,隔阂 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

154

scorched

|

|

| 烧焦,烤焦( scorch的过去式和过去分词 ); 使(植物)枯萎,把…晒枯; 高速行驶; 枯焦 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

155

incisions

|

|

| n.切开,切口( incision的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

156

allied

|

|

| adj.协约国的;同盟国的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

157

texture

|

|

| n.(织物)质地;(材料)构造;结构;肌理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

158

allusions

|

|

| 暗指,间接提到( allusion的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

159

scattered

|

|

| adj.分散的,稀疏的;散步的;疏疏落落的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

160

Mediterranean

|

|

| adj.地中海的;地中海沿岸的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

161

poetical

|

|

| adj.似诗人的;诗一般的;韵文的;富有诗意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

162

cannibalism

|

|

| n.同类相食;吃人肉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

163

devoid

|

|

| adj.全无的,缺乏的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

164

exempted

|

|

| 使免除[豁免]( exempt的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

165

morass

|

|

| n.沼泽,困境 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

166

reverted

|

|

| 恢复( revert的过去式和过去分词 ); 重提; 回到…上; 归还 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

167

exigencies

|

|

| n.急切需要 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

168

westward

|

|

| n.西方,西部;adj.西方的,向西的;adv.向西 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

169

rudiments

|

|

| n.基础知识,入门 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

170

scotch

|

|

| n.伤口,刻痕;苏格兰威士忌酒;v.粉碎,消灭,阻止;adj.苏格兰(人)的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

171

dense

|

|

| a.密集的,稠密的,浓密的;密度大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

172

alder

|

|

| n.赤杨树 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

173

stumps

|

|

| (被砍下的树的)树桩( stump的名词复数 ); 残肢; (板球三柱门的)柱; 残余部分 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

174

margin

|

|

| n.页边空白;差额;余地,余裕;边,边缘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |