Relation of Human Remains2 to those found in Tumuli in Britain.—The Dolicho-cephali and Brachy-cephali.—Their Range in Britain and Ireland—in France.—The Caverne de l’Homme Mort.—The Sepulchral4 Cave of Orrouy.—The Tumuli.—In Belgium.—The Sepulchral Caves of Chauvaux and Sclaigneaux.—The Dolicho-cephali of the Iberian Peninsula—Gibraltar—Spain.—Cueva de los Murcièlagos.—The Woman’s Cave near Alhama in Granada.—The Guanches of the Canary Isles5.—Iberic Dolicho-cephali of the same race as those of Britain, France, and Belgium—Cognate6 or Identical with the Basque Race.—Evidence of History as to the Peoples of Gaul and Spain.—The Basque Populations the Oldest.—The Population of Britain.—Basque characters in Present Population of Britain and France.—Whence came the Basques?—The Celtic and Belgic Brachy-cephali.—The Ancient German Race.—General Conclusions.

The Relation of the Human Remains to those found in British Tumuli.

Before we examine the relation of this ancient neolithic race of men to those who have left their remains in tumuli and caves in other regions, it is necessary to define the cranial terminology7, as adopted by Professors Busk, Huxley, Dr. Thurnam, and other high authorities.190 The term “cephalic index” indicates “the ratio of the extreme transverse to the extreme longitudinal diameter of the skull8, the latter measurement being taken as unity9” (Huxley).

The most convenient classification of crania is that adopted by Dr. Thurnam and Professor Huxley,117 and based on the cephalic index.

I. Dolicho-cephali, or long skulls10 with cephalic index at or below ·73

Subdolicho-cephali ” ” from ·70 to ·73

II. Ortho-cephali, or oval skulls ” ·74 to ·79

Subbrachy-cephali ” ·77 to ·79

III. Brachy-cephali or broad skulls at or above ·80

It has been objected that skull form is of no value in determining race, because it varies so much at the present time among the same peoples, presenting the extremes of dolicho- and brachy-cephalism as well as every kind of asymmetry11. This, however, is due to our very abnormal conditions of life, and to the mixture of different races brought about by the needs of commerce, as in Manchester and Vienna, as is pointed12 out by Mr. Bradley.118

In prehistoric13 times, neither of these causes of variation made themselves seriously felt. There was little, if any, peaceful movement of races, but war was the normal condition, and society was not sufficiently14 advanced to remove man from the influence of his natural environment. The objection may therefore be dismissed as not applicable to the skulls in question.

The extent to which abnormal conditions of life are191 capable of modifying the shape of skulls may be gathered from the comparison of the skull of an Irish hog15 with that of its ancestor the wild-boar, or even that of a hy?na kept in confinement16 with that of a wild animal of the same species. (See Osteol. Series, Brit. Mus.)

The British Dolicho-cephali and Brachy-cephali.

The materials for working out the craniology of Europe, in prehistoric times, do not justify17 any sweeping18 conclusion as to the distribution of the various races, but those which Dr. Thurnam (op. cit.) has collected in Britain offer a firm basis for such an inquiry19. In the numerous long barrows and chambered “gallery graves” of our island, which from the invariable absence of bronze, and the frequent presence of polished stone implements21, may be referred to the neolithic age, the crania belong, with scarcely an exception, to the first two of these divisions. In the round barrows, on the other hand, in which bronze articles are found, they belong mainly to the third division, although some are ortho-cephalous. Sometimes, as in the case of Tilshead, the crania in the primary interment, over which the long barrow was raised, are long, while those in the secondary, which have been made after the heaping up of the barrow, are broad.

On evidence of this kind Dr. Thurnam concludes, that Britain was inhabited in the neolithic age by a long-headed people, and that towards its close it was invaded by a bronze-using race, who were dominant23 during the bronze age. This important conclusion has been verified by nearly every discovery which has been made in this country since its publication. The long skulls graduate192 into the broad, the oval skulls being the intermediate forms; and this would naturally result from the intermingling of the blood of the two races. There may, however, have been a tendency towards ortho-cephalism in the dolicho-cephali, without any admixture of foreign blood, since absolute unity of form could not be expected.

The skull of the primary interment in the barrow of Winterbourne Stoke is taken by Dr. Thurnam as typical of the dolicho-cephalic class. “The greatest length is 7·3 inches (the glabello-inial diameter 7·1 inches); the greatest breadth is 5·5 inches, being in the proportion of 75 to the length taken as 100. The forehead is narrow and receding25, and moderately high in the coronal region, behind which is a trace of transverse depression. The parietal tubers are somewhat full, and add materially to the breadth of this otherwise narrow skull. The posterior borders of the parietals are prolonged backwards26, to join a complex chain of Wormian bones in the line of the lambdoid suture. The superior scale of the occiput is full, rounded, and prominent; the inion more pronounced than usual in this class of dolicho-cephalic skulls. The superciliaries are well marked, the orbits rather small and long; the nasals prominent, the facial bones short and small; the molars flat and almost vertical27; the alveolars short, but rather projecting. The mandible is comparatively small, but angular; the chin square, narrow, and prominent.”119

Dolicho-cephalic skulls in general (and in part ortho-cephalic) are possessed28, according to Dr. Thurnam, of the following characters (Vol. iii. p. 69):—“The supraciliary ridges29 are less strongly marked than in the brachy-cephalic. There is none of the prognathism, exaggerated193 malar breadth or great width of the nasal openings, which give such an air of savageness31 and ferocity to the New Caledonians and Caroline Islanders; but the very reverse of all these. They are indeed more orthognathic even than many Europeans, and the facial characters generally are mild, and without exaggerated development in any one direction.” Their faces are oval. The upper jaw33 is small, and the sockets34 of the incisors and canine35 almost vertical. The supra-occipital region is full and rounded, and there is a post-coronal annular36 depression on the skull, termed by Dr. Gosse “tête annulaire.” The length is mainly due to the development of the occiput, a condition that is termed by M. Broca “dolicho-cephalie occipitale,” as distinguished37 from the “dolicho-cephalie frontale” of other races. The teeth are worn flat. The bones associated with the skulls of this character show that the stature38 of the race was short, 5 feet 5 inches being the average height.

In the brachy-cephalic, or broad skulls, on the other hand, the supraciliary ridges are more strongly marked than in the preceding group; the cheek-bones are high and broad, the sockets for the front teeth are oblique39, and the mouth projects beyond the vertical dropped from the forehead, presenting the character of prognathism. The face, instead of being oval, is angular or lozenge-shaped. On the back of the head the occipital tuberosity, or probole, is the most prominent feature, and there is also generally an occipital flattening40, which may have been caused by the use of an unyielding cradle-board in infancy41. The entire maxillary apparatus42 is so largely developed, that the term “macrognathic,” introduced by Professor Huxley, is particularly applicable to them. The “type mongoloide” of Dr. Pruner-Bey194 is closely allied43 to, if not identical with, this form of skull.

The stature of the British brachy-cephali is much greater than that of the dolicho-cephali, the average for the adult male being 5 feet 8·4 inches, according to Dr. Thurnam.

The human remains from the caves and chambered-tombs of Denbighshire belong to the first of these divisions, in the possession of every one of the characters assigned to it by Dr. Thurnam, although the crania belong to the ortho-cephalous portion of the series, that is, tending towards broad-headedness. It may therefore be inferred that they belong to the same race as the neolithic raisers of the long-barrows, a race which we shall presently see to be identical with the ancient Iberians and modern Basques.

The Range of the Dolicho-cephali in Britain and Ireland.

The same class of human remains has been obtained from caves in other districts in Great Britain. In the Oxford44 Museum a human skull, from the cave of Llandebie, possesses cephalic index of ·72; while a second, from the cave of Uphill in Somersetshire, explored by Mr. James Parker in 1863, measures ·723. (See p. 197.) The latter was associated with rude pottery45, charcoal46, and the remains of the following animals: the wild-cat, dog, fox, badger47, pig, stag, Bos longifrons, goat, and water-rat. Most of the remains belong to young individuals, and some have been gnawed48 by dogs, wolves, or foxes.

195 In Yorkshire a human femur presenting an enormous development of the linea aspera, which implies the possession of the platycnemic character, has been met with in a cave in King’s Scar, near Settle (see p. 113), and fragments of a long skull are preserved in the Museum at Leeds from that of Dowkerbottom.

Professor Turner has described120 the remains found in a cave in the Old Red sandstone on the shore of the bay of Oban in 1869 by Mr. Mackay. There were two human skeletons, along with the broken and burnt bones of the roe49 and stag, limpet-shells, flint nodules, and flint flakes50. One of the leg-bones is platycnemic, and the fragments of skull may probably be referred to the dolicho-cephalic type.

The same type of skull has also been obtained by the Rev32. Canon Greenwell, from the neolithic tumuli of Yorkshire, along with the same group of animals as in the caves at Perthi-Chwareu, the Bos longifrons, goat, horse, dog, and stag; and Professor Rolleston, F.R.S., informs me that some of the associated human leg-bones are platycnemic. It is also recognized by Professor Huxley as identical with his river-bed type of skulls from alluvial52 deposits near Muskham in the valley of the Trent, Ledbury Hall in the valley of the Dove, and in Ireland from the bed of the Nore in Queen’s County, and from that of the river Blackwater. To it also Professor Huxley refers121 five or six out of the seven skulls obtained by Mr. Laing from the stone cists in the burial mound53 at Keiss in Caithness, and associated with rude weapons and implements of bone and stone. They196 probably belonged to the inhabitants of the neighbouring burgh, or circular stone dwelling54, in and around which were the broken bones of the following animal remains: the Bos longifrons, goat, stag, hog, horse, dog, fox, grampus or small whale, dolphin or some other small cetacean, great auk (Alca impennis, now extinct in Europe), lesser55 auk, cormorant56, shag, solan goose, cod57, lobster58, and shell-fish. A lower jaw also of a child, broken after the same manner as other refuse bones, is considered by Professor Owen and Mr. Laing to prove that human flesh was sometimes used for food. The reindeer59 was living in the district at this time, since its remains have been identified by Dr. Campbell from the Harbour mound, one of the many refuse-heaps in the neighbourhood.

The same kind of skull is also described by Professor Wilson under the name of “boat-shaped” or “kumbe-cephalic,” from the ancient stone chambers60 and tumuli of Scotland.122

In the Table on the next page, showing the relative size and shape of the more important long skulls of Britain and Ireland, it will be seen that the extreme long-headedness of those from the long barrows is not possessed by those either of the caves and tombs of Denbighshire or of the river-bed type of Huxley, represented by the skulls from Muskham, Ledbury, Blackwater (Ireland), and Keiss.

The greater breadth of the skulls from the caves and tombs of Denbighshire, as compared with those of the typical long skulls from the long barrows, may possibly be due to a mixture with the broad-headed race. In that case, however, none of the tallness, or prognathism,197 of the latter has been handed down. It is most probably a mere61 variation within the limits of one race, and is unaccompanied by the fusion62 of dolicho-cephalic with brachy-cephalic characters, such as M. Broca and Dr. Thurnam have observed in the skulls from tombs and caves in France.

(Image of Table)

Skulls. Length. Breadth. Height. Circum-

ference. Latitud.

or Ceph.

Index. Alt.

Index.

Mean of 48 males, Brit., Thurnam, long barrows 7·7 5·5 5·62 21·3 ·715 ·730

Mn of 19 females, Brit., Thurnam long barrows 7·45 5·3 5·3 20·6 ·710 ·730

Mn of 10 skulls, Perthi-Chwareu Cave 7·07 5·5 5·6 20·0 ·765 —

Skull from Llandebie Cave 7·3 5·3 — — ·720 —

” Uphill 7·36 5·43 — — ·723 —

Mean of 6 skulls from Keiss. (Huxley) 7·22 5·45 5·19 — ·755 ·716

Skull from Muskham (Huxley) 7·0 5·4 — — ·770 —

” Ledbury Hall (Huxley) 7·15 5·5 — — ·770 —

” Blackwater, Ireland (Huxley) 7·2 5·65 — — ·780 —

From the examples given in the preceding pages it is evident that, in ancient times, long-headed men of small stature inhabited the whole of Britain and Ireland, burying their dead in caves, but more generally in chambered tombs. They were farmers and shepherds, and in this country in the neolithic stage of culture. In the solitary63 case offered by the Harbour mound at Keiss they were cannibals.123

The Range of the Brachy-cephali.

No human remains of the brachy-cephalic, or broad type, as defined by Dr. Thurnam have been obtained198 from the caves in Britain. The evidence, however, is decisive that, in the Bronze age, a tall, round-headed, rugged-featured race occupied all those parts of Britain and Ireland that were worth conquering, and drove away to the west or absorbed the smaller neolithic inhabitants. And the identity of their skull-form, in the series of interments in the round and bowl-shaped barrows, extending from the Bronze age down to the date of the Roman occupation of Britain, shows that, both in the North and the South, this large-sized coarse-featured people was in possession at the time of the Roman conquest.

The size and shape of the typical broad crania may be gathered from the first two columns of the following Table, which is an abstract of those published by Dr. Thurnam in “Crania Britannica,” and the “Memoirs of the Anthropological64 Society.”

199

Measurements of British Brachy-cephali, and Gaulish and Belgic Brachy-cephali and Dolicho-cephali.

Skull. Date.B Length. Breadth. Height. Circum-

ference. Latitudinal65

or Cephalic

index. Altitudi-

nal index.

TYPICAL BROAD SKULLS.—BRITAIN.

Mean of 56 males, Brit. Round Barrows N.B.I. ?7·28 5·9? 5·6 21·1 ·81 ·77

Mean of 14 females, Brit. Round Barrows N.B.I. 6·9 5·6? 5·3 20·? ·81 ·77

LONG AND SHORT SKULLS.—FRANCE.

Tumulus, Noyelles-sur-mer-Somme N. 6·9 5·6p 5·5 20·3 ·81 ·79

“Grotto,” Nogent les Vièrges, Oise N. 7·2 5·8p 5·5 21·? ·80 ·76

” ” ” ” 7·3 5·2p 5·2 20·1 ·71 ·71

” ” ” ” 7·1 5·7p 5·2 20·8 ·80 ·73

” ” ” ” 6·9 5·9p 5·5 20·9 ·85 ·79

” ” ” ” 7·3 5·4p 5·5 20·6 ·74 ·75

” ” ” ” 7·4 5·2p 5·6 20·8 ·70 ·75

Dolmen Du Val, Senlis, Oise N. 6·6 5·6p 5·4 19·7 ·84 ·81

” ” ” ” 7·1 5·5p 5·6 20·2 ·77 ·78

” ” ” ” 7·2 5·5? 5·8 20·8 ·76 ·80

” ” ” ” 7·2 5·8? — — ·80 —

” Chamant ” ” N. 7·4 5·3? — — ·71 —

” ” ” ” 7·1 5·5? — — ·78 —

” ” ” ” 7·4 5·5? 5·4 — ·74 ·72

Cave, Orrouy, Oise N.B.(?) 7·4 5·8? 5·3 21·2 ·78 ·72

” ” ” 7·1 5·8p 5·3 — ·77 ·74

” ” ” 7·2 5·4p 5·7 20·1 ·75 ·81

” ” ” 7·1 5·9p 5·6 20·7 ·83 ·78

” ” ” 6·7 5·5p 5·4 19·2 ·82 ·80

” ” ” 6·6 5·6p 5·5 19·9 ·85 ·83

” ” ” 7·2 5·9? 5·4 20·9 ·81 ·75

” ” ” 6·8 5·75 5·1 20·4 ·84 ·75

” ” ” N. 7·4 5·8? 5·7 — ·78 ·77

” ” ” 7·2 5·9? — 20·8 ·81 —

Lombrive, Ariège N. 6·7 5·5? 5·5 19·2 ·82 ·82

Dolmen, Meudon, Seine et Oise 7·? ?5·95p 5·9 20·7 ·85 ·84

” ” ” ” 7·2 5·7? 5·5 20·8 ·79 ·76

Lozerres 7·3 5·8p 5·7 21·? ·79 ·78

Tomb, Maintenon; Eure et Loire ?7·25 5·5? — 20·3 ·75 —

” ” ” ” 7·7 5·5? — 20·8 ·71 —

Tumulus, Bougon, Deux Sèvres 6·7 5·4p — 20·? ·80 —

Dolmen, Meloisy, C?te d’Or N. 7·3 5·5? — 20·9 ·75 —

Avignon(?), Vaucleuse 6·9 5·8? — 20·7 ·84 —

” ” 7·8 5·5p — 21·8 ·70 —

Genthod, Geneva I. 7·4 5·6p 5·5 21·1 ·75 ·74

” ” 6·9 5·6p 5·4 20·5 ·81 ·78

Mean 7·1 5·6? 5·5 20·5 ·78 ·77

Judge’s Cave, Gibraltar (Busk) (?) 6·9 5·4? 5·4 19·5 ?·792 —

Chauvaux Cave (Virchow) N ?7·35 5·3? 5·3 — 71·8?? 1·8

Sclaigneaux Cave. Skull 1. (Arnould) N ?7·35 6·5? 5·4 — 81·1?? 73·7?

” ” ” 2. ?7·25 6·25 ?5·25 — 81·6?? 70·6?

” ” ” 3. 6·9 5·75 — — — —

” ” ” 4. ?6·95 — — — — —

B N, Neolithic; B, Bronze; I, Iron.

The Range of the Dolicho-cephali and Brachy-cephali in France in the Neolithic Age.—The Caverne de l’Homme Mort.

The researches of M. Broca and Dr. Thurnam into the caves and tombs of France prove that the small dolicho-cephali and the tall brachy-cephali lived in that country in the neolithic age. We are indebted to the former for a most important account of the Caverne de l’Homme Mort, which reproduces all the essential points which we have observed in the sepulchral caves of Denbighshire.

200

The Caverne de l’Homme Mort124 is situated66 in a lonely ravine that penetrates67 the wild limestone68 plateau, in the south-west of the department of Lozère, near the hamlet of Vialle, in the commune of St. Pierre des Tripiés. It was discovered by the peasants, and its contents were partially69 disturbed by their search after hidden treasure before it was explored by Dr. Prunières. In front of the cave was a platform, composed of earth mingled70 with fragments of charcoal, forming a layer about forty centimetres thick, in which were the stones of seven hearths71, flint-flakes and scrapers, lance-heads, broken bones of the hare, fallow-deer, roe, pig (or wild-boar). All the flints were worked, and one lance-head had been chipped out of the stump72 of a celt and presented portions of the polished surface, thus fixing the neolithic age of the accumulation. Coarse pottery was also met with.

The bones of the hare were very abundant, and proved that there was no prejudice against the use of its flesh. In the caves of Perthi-Chwareu we have also seen that this was the case.

The refuse-heaps ceased abruptly73 at the entrance of the cave, at a point where the traces of a wall, composed of large stones, was visible. Immediately behind this were human bones, in a thick layer of dry sand, scattered74 about in the wildest confusion, which was probably the result of successive interments, as well as of subsequent disturbance75 by burrowing76 animals and treasure-seekers. Two bone-points and a flint arrow-head were the only implements discovered within the sepulchral chamber20.

Two small human bones, bearing undoubted marks of having been burnt, were discovered in the refuse-heap; but they do not, as M. Broca justly observes, imply the practice of cannibalism77, since they may have fallen out201 of the burial-place, and subsequently have come into contact with the fire on one of the hearths.

It is impossible to estimate the number of interments in this cave. Exclusive of the many skulls which have been destroyed or lost, M. Prunières obtained nineteen very nearly perfect, which are described by M. Broca as seven male, six female, three of uncertain sex, and three children. They are remarkable78 for the softness of their contours, the delicacy79 of their features, and the orthognathism of their faces. The forehead is wide and high, and the vertex and the occipital region of the skull well rounded. The cephalic index varies between ·680 and ·78, the mean of the whole series being ·732.

M. Broca remarks, that these crania contrast strongly with those of the present broad-headed inhabitants of the district, and that they differ from those found in the dolmens by M. Prunières in their greater length, in the smallness of their features, and the weakness of their muscular impressions. The study of the bones of the skeleton confirms these differences. The men who buried their dead in the Caverne de l’Homme Mort were smaller than the dolmen builders, their bones were more slender, and they were altogether a less muscular race. They are considered by M. Broca to represent the neolithic aborigines; and if his description and measurements be compared with those of the dolicho-cephali of Britain, given by Dr. Thurnam (p. 191 et seq.), it will be seen that they are identical with the latter, which is the oldest race yet known to have occupied Great Britain since the close of the pleistocene period.

At a little distance from the sepulchral cave, and in the same ravine, M. Broca explored a large cavern3, which had been occupied, probably by the same people, since202 the same kind of instruments were discovered as in the refuse-heap. So that we have here, side by side, the abode80 and the sepulchre of the same ancient tribe.

The Sepulchral Cave of Orrouy.

The sepulchral cave of Orrouy (Oise) described by M. Broca, in which the remains of about fifty individuals were interred81, furnished both types of skull, united, according to Dr. Thurnam and M. Broca,125 by a series of intermediate forms, that prove a fusion of blood between the broad- and the long-headed peoples. On referring to the preceding Table (p. 199) it will be seen that the cephalic index varies from ·75 to ·88. Eight out of the series of twenty-one skulls united the characteristic dolicho-cephalous fore-head with the brachy-cephalous middle and hind-head. “We have here,” writes Dr. Thurnam, “a veritable hybrid82 form of cranium, resulting from the mixture or crossing, under certain circumstances unknown to us, of a dolicho-cephalous with a brachy-cephalous race.”

“... In the Orrouy skulls of hybrid form, two encephalic growth-tendencies appear to me distinguishable; one, the longitudinal or fronto-occipital; the other a transverse, or bi-parietal and temporal one. Now the remarkable supramastoid depressions, visible in the hindhead of these skulls, seem to be well explained by the idea of an intersection83 or crossing of these two tendencies in the brain-growth; corresponding, as they must have done, to the angles formed by the posterior surfaces of the middle, the lower surfaces of the posterior203 and temporal lobes84 of the cerebrum, and the upper surface of the cerebellum.”126

In eight out of thirty-four humeri the fossa of the olecranon is perforated.

The human remains occurred in the same confusion as at Perthi-Chwareu, and were associated with fragments of coarse pottery, flint flakes, and bones of ruminants. The occurrence of polished stone celts indicates the neolithic age of the interment.

Skulls from French Tumuli.

Both long and broad skulls also occur in the chambered tombs of France, although the latter by far predominate. Those from the Long Barrow at Chamant are dolicho-cephalic and ortho-cephalic, with cephalic index ranging from ·71 to ·78 (Broca), and other similar cases are quoted by Dr. Thurnam from Noyelles-sur-Mer, Fontenay, and other tumuli. In the large sepulchral chamber at Meudon, that contained 200 skeletons, the majority of the skulls were brachy-cephalic, although twenty of them were of the ortho-cephalic type. This mixture may be accounted for, most probably, by the two races, which are clearly defined from each other in Britain, being intermingled in France.

Dr. Thurnam, summing up the whole evidence as regards the distribution of races in the tombs of Gaul, concludes that the two races came into contact in Gaul at an earlier period in the neolithic age than in Britain. And this must necessarily have been the case from the geographical85 position of our island, which could only be invaded, in those times, by the races in possession of the204 contiguous mainland of France and Belgium. Both these regions must have been conquered before an invasion could have taken place.

The Dolicho-cephali of the Iberian Peninsula, Gibraltar.

The researches carried on from 1863 to 1868, by Captain Brome, aided by Dr. Falconer and Professor Busk,127 into the caves of Gibraltar, have resulted in the proof that, in the neolithic age, that barren rock was inhabited by a race of men identical with that which is found in the long barrows and caves of Great Britain.

The enlargement of the military prison on the top of Windmill Hill revealed the existence of a deep fissure86, containing dark earth, mingled with charcoal and broken bones, which led into a series of chambers. The upper of these is described by Captain Brome as being completely choked up to the roof with earth, charcoal, and decomposed87 bones of mammals, birds, and fishes, flint flakes, and pottery. Below were two floors of stalagmite, filled with loose stones and earth, through which a shaft88 penetrated89 into a fissure at a lower level, leading into a lower chamber that had a free communication with the surface, since the current of air was so strong as to extinguish the lamps. In this also human remains and works of art were met with. The passages were very complicated, and in some of them a red breccia contained the remains of the pleistocene mammals, the spotted90 hy?na, the Rhinoceros91 hemit?chus, and others. This series of passages and chambers is described by205 Captain Brome and Professor Busk as “Genista Cave No. 1.”

A second, or “Genista, No. 2,” was discovered by Captain Brome opening on the surface near the West Cliff, with its floor covered with stalagmite, under which was the same class of remains as that above mentioned. Subsequently a third and fourth, “Genista, 3 and 4,” were explored with the same results, of which the latter, opening on the face of a vertical cliff 40 feet below the summit, from its difficulty of access must have been used as a place of refuge rather than of habitation or burial. With this exception, the whole group of Genista Caves contained human bones, resting in the greatest confusion, and proving that since the bodies had been interred the contents had been disturbed, either by the burrowing of animals or by the action of water, pools of which were present in some of the chambers. Evidence of the former presence of water was to be seen in the sheets of stalagmite on most of the floors. The same confusion would result, as is suggested by Professor Busk, by interments at successive times. The intimate association of the fractured bones of the animals, and the charcoal, broken pottery, and other traces of occupation, with the human bones, may be accounted for in the same manner as the similar mixture of remains in the caves of Denbighshire. If the caves had been inhabited at one time, and subsequently set apart for burials, the human bones would become intermingled with the accumulation of refuse on the floors by the causes above mentioned.

The bones of the animals associated with the human remains belong, according to Professor Busk, to the domestic ox of various sizes, goat, ibex, hog, arvicola,206 hare, rabbit, badger, dog, and a species of phoc?na, fish, birds, and marine92 and land molluscs. The pottery is for the most part hand-made, coarse and imperfectly burnt; and the vessels94 in some cases had singular perforated spouts95, similar to those still in use by the Kabyles of Algeria, and some of the Berber tribes. Some of it, however, is of a fine red ware51 turned in the lathe96, and probably introduced at a later period, even, as remarked by Mr. Franks, after the Roman occupation of Spain, to which he refers a bronze fish-hook, the only metallic97 article found in the group of caves. The implements of bone consist of a needle, and rounded pins and spikes98. One cannon-bone of a small ox bears marks of sharp cuts with an edge of metal, inflicted99 probably, as Professor Busk suggests, “in an attempt to hamstring the animal, as is sometimes done at the present day in the Spanish bull-ring.” It may possibly be more modern than the stone implements found in the same cave.

The associated stone articles are celts of polished greenstone, similar to that found in the neolithic cave at Perthi-Chwareu (Fig100. 38), flakes, a greenstone chisel101, querns and rubbing-stones, a whetstone perforated for suspension, and a fragment of an armlet made of alabaster102. A small lump of coarse plumbago may have been used for personal ornament103.

The human remains examined by Professor Busk belonged to a large number of individuals of all ages, and are for the most part in a fragmentary condition. Some of the thigh-bones are carinate, and remarkable for the enormous development of the linea aspera and the thickness of their walls (Fig. 57), the medullary cavity being reduced to a small size, as in those figured from the tumulus at Cefn. Some of the207 tibi? are platycnemic, presenting the peculiar104 lateral105 flattening which first attracted the attention of Dr. Falconer and Professor Busk (Figs106. 49, 50, and 51), but which M. Broca has since determined107 in the tumuli and caves of France, and I have discovered in those of Denbighshire (p. 177).

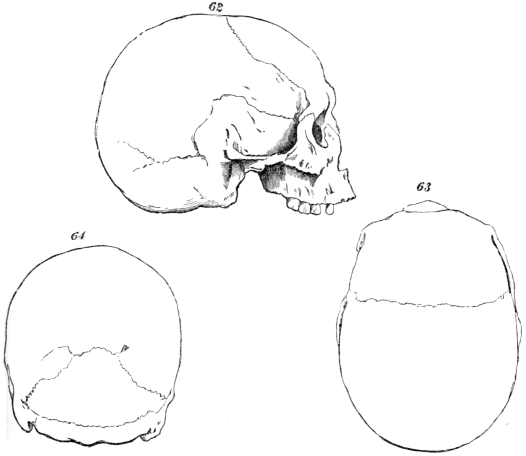

Figs. 62, 63, 64.—Cranium from Genista Cave (Busk).

The only two crania sufficiently perfect to allow of a comparison being made, from Genista Cave No. 3, are perfectly93 symmetrical, and belong to a high type (Figs. 62, 63, and 64). “They are dolicho-cephalic, quite orthognathous, and wholly aphanozygous. In one the frontal sinuses are considerably108 more developed than they are in the other, but in neither is there any thickening208 of the supra-orbital border” (Busk). The teeth are worn flat. They both belonged to men in the prime of life. A third skull, from Genista Cave No. 1, belongs to the same type. The measurements of the two most perfect skulls are given in the same table as those from North Wales (p. 171).

Gibraltar has also been occupied in ancient times by broad-headed men, similar, in M. Broca’s opinion, to those interred in the cave of Orrouy. In 1864 human bones, together with a skull (for measurements see p. 199), were dug out of the Judge’s Cave by Sir James Cochrane. The tibi? are platycnemic, and the skull is described by Professor Busk as being “perfectly symmetrical, brachy-cephalic, slightly prognathous, but with vertical teeth, aphanozygous. The forehead is well arched, and the supra-orbital border slightly elevated, the orbits being square, and the nasal opening elongated109 and pyriform.” The cephalic index is ·792. The age of these skeletons is uncertain.

Spain.—Cueva de los Murcièlagos.

Professor Busk128 calls attention to the fact, that a long skull similar to that from Gibraltar has been found in Spain, in an ancient copper110-mine of the Asturias, together with hammers made of antler, and that it bears “the closest possible resemblance” to the Basque skulls, described by M. Broca, from Guipuscoa on the Spanish and St. Jean de Luz on the French side of the Pyrenees. He points out, also, the resemblance which exists between the crania figured by Don Gongora y Martinez, from the caverns111 and dolmens of Andalusia and those under209 consideration; finally arriving at the conclusion that “a pretty uniform priscan race at one time pervaded112 the peninsula from one end to the other, and that this race is at the present day represented by, at any rate, a part of the population now inhabiting the Basque provinces.”

In the work of Don Manuel Gongora y Martinez129 referred to, there is a most interesting account of the prehistoric antiquities113 of Andalusia. Several interments are described in the Cueva de los Murcièlagos, a cave running into the limestone rock, out of which the grand scenery of the southern part of the Sierra Nevada has been, to a great extent, carved. In one spot, a group of three skeletons was met with, one of which was adorned114 with a plain coronet of gold, and clad in a tunic115 made of esparto-grass, finely plaited, so as to form a pattern which resembles some of the designs on gold ornaments116 from Etruscan tombs. At a spot further within, a second group of twelve skeletons lay in a semicircle, around one considered by Don Manuel to have belonged to a woman, covered with a tunic of skin, and wearing a necklace of esparto-grass, a marine shell pierced for suspension, the carved tusk117 of a wild boar, and earrings118 of black stone. There were other articles of plaited esparto-grass, such as baskets and sandals; flint flakes, pieces of a white marble armlet, polished axes of the type of fig. 38, bone awls, and a wooden spoon, together with pottery of the same type as that from Gibraltar, fragments of charcoal, and bones of animals.

Although, in this cave, there were no traces of metal, except gold, in a second, in the same neighbourhood,210 similar interments were met with in association with copper (bronze) implements, and with pottery of the same kind.

These interments in caves are of the same order as those from Gibraltar; and since the skulls agree with those from the latter, there can be little doubt but that, in the neolithic age, the long-headed small race under discussion had possession of the southern provinces.

The Woman’s Cave, near Alhama.

This conclusion derives119 additional support from the discoveries subsequently made by Mr. McPherson130 in the Woman’s Cave, near Alhama, in Grenada, of implements of bone, flint, and greenstone of the neolithic age, mingled with charcoal, pottery, and human skeletons of the same type as those from Gibraltar. The human skull, figured by Mr. McPherson, is dolicho-cephalic, and the thigh-bone is remarkable for the extreme development of the linea aspera, which assumes the form of a stout120 ridge30 sweeping from one extremity121 of the shaft to the other.

This long-headed race, burying their dead in caves, also erected122 dolmens in Andalusia. In the dolmen of De los Eriales131 human remains were discovered along with bronze (copper?) lance-heads, and pottery of the same sort as that of the caves. It is, therefore, evident that the practice of burial in caves, and of erecting123 dolmens, was carried on by the same people in Britain, in France, and in Spain.

211

The Guanches of the Canary Isles.

The Guanches,132 the ancient inhabitants of the Canary Isles, are considered by Berthollet, Glas, and other high authorities, to be allied to the Berbers of North Africa in language. At the time of their discovery and conquest by the Spaniards, they are described by Miss Haigh as being unacquainted with the use of any metal, and as fashioning their weapons out of a black, hard stone. The Guanches of Teneriffe lived principally in caves, preferring for their winter residence those near the coast, and “in the summer those in the higher parts in the interior of the island, whence they could enjoy the fresh air of the hills.” Some of these caves have been excavated124 by the hand of man, and are divided into square chambers, containing rock-hewn benches, “and deep niches125 made to contain vessels of milk or water.” They had also stone houses, thatched with straw or fern. They also buried their dead in sepulchral caves, belonging each to a family or clan126, entrances to which are carefully concealed127, and are now discovered only by accident. In them the dead were placed either upright, or lying side by side on wooden scaffolds, after having been prepared with salt and butter and thoroughly128 dried and wrapped in the tanned skins of sheep or goat. In some cases the prepared body was placed in the sitting posture129.

They were possessed of a settled government by “Menceys,” or chiefs subordinate to one head, and were divided into “nobles and common people, and had a code of punishment for the robber, murderer, and adulterer.”

212 Their food consisted of sheep and goats, roasted barley130 ground between two stones, and the fruit of the arbutus, date-palm and fig, as well as fish and rabbits. Their fences were made of reed, their ropes and nets of rushes, and their baskets, mats, and bags, of palm-leaves. They manufactured vessels out of clay or hard wood, needles of fishbones, beads131 of clay, and they especially excelled in the art of tanning. The civilization of this very interesting people may fairly be taken to be a fragment of that of North Africa and of Europe in the neolithic age, protected by insulation132 from the influences by which it was swept away from the countries bordering on the shores of the Mediterranean133, just as the old Norse customs and legends are preserved by the present inhabitants of Iceland in greater purity than in Norway.

The Berbers are viewed by Professor Busk as of the same non-Aryan stock as the Basque, and the civilization of the Guanches may therefore be taken to represent that of the Iberic peoples of Spain, among whom caves were used in like manner for habitation and burial.

Iberic Dolicho-cephali of the same Race as those of Britain.

If this group of Iberic skulls be compared with those from the caves and tumuli of Great Britain (see Table, p. 197 and that below) it will be seen, that what Professor Busk observes of the ancient population of Spain is equally true of that of our country in the neolithic age. And the identity of form is especially remarkable in the crania from the sepulchral caves at Perthi-Chwareu,213 the difference between them being so small as to be of little account:—

Length. Brdth. Height. Circum-

ference. Ceph.

index.

Mean of 10 skulls from Perthi-Chwareu 7·07 5·5 5·6 20·0 ·765

Mean of 2 skulls from Genista Cave, No. 3 (Busk) 7·35 ?5·55 5·9 20·7 ·755

Mean of 40 male Basque skulls from Guipuscoa (Thurnam) 7·2? 5·5 5·4 — ·760

Mean of 20 female, ditto 6·9? 5·3 5·0 — ·760

Mean of 19 skulls,chiefly male 7·4? 5·6 5·4 — ·760

Mean of 57 female ditto, St. Jean de Luz 7·02 5·6 — — ·799

The Dolicho-cephali cognate with the Basque.

Nor can the truth of Professor Busk’s conclusion, that the group of skulls in question belong to a people akin134 in blood to the modern Basques, be disputed. We are indebted to M. Broca133 for the elaborate description of seventy-eight Basque crania from a village cemetery135 in Guipuscoa, and of fifty-eight from an ossuary at St. Jean de Luz, in which they had been collected in the reign24 of Francis I., 1532. In both these groups the long and oval types predominated, the broad type being represented by 6·4 (Thurnam) per cent. in the one, and 37·36 per cent. (Broca) in the other; a difference that is doubtless caused by the greater mixture of blood in the south-west of France than in the north-west of Spain, shut off from the broad-headed Gallic tribes by the Pyrenees.134 Six214 skulls, obtained by Professor Virchow from Bilbao, agree in all particulars with those from Guipuscoa. M. Broca has further shown, that this group of Spanish skulls offers all the characters of the black-haired, swarthy, oval-faced, Basque population of the surrounding region, and it therefore follows, that they may be taken as standards of comparison, as typical of the ancient Basque crania, modified, it may be, to some extent, by the infusion136 of other blood. Their agreement, therefore, with the skulls from Gibraltar implies that the latter are also Basque. And since they agree also with those from the cave of Perthi-Chwareu, as may be seen in the preceding Table, the men who buried their dead in the caves of North Wales in the neolithic age, are proved to belong to the same stock.

The same long-headed, small race also inhabited France, side by side with the broad-headed Gallic tribes; and since to it belong the skeletons in the Cave de l’Homme Mort, which M. Broca refers to the neolithic aborigines, it may reasonably be concluded that in Gaul, as in Britain, it was the older of the two races. The two have also been met with in the caves of Belgium. If we allow that an aboriginal137 Basque population spread over the whole of Britain, France, and Belgium, and that it was subsequently dispossessed by broad-headed invaders138, the two extremes of skull-form and of stature, and of the gradations between them, may be satisfactorily explained. And this view coincides with the well-ascertained facts of history.

Dr. Thurnam was the first to recognize that the long skulls, out of the long barrows of Britain and Ireland, were of the Basque or Iberian type, and Professor Huxley holds that the river-bed skulls belong to the215 same race.135 (Compare Table p. 197 with the preceding.) We have therefore proof, that an Iberian or Basque population spread over the whole of Britain and Ireland in the neolithic age, inhabiting caves, and burying their dead in caves and chambered tombs, just as in the Iberian Peninsula also in the neolithic age.

Dolicho-cephali and Brachy-cephali in Neolithic Caves of Belgium.—Chauvaux.

Both these forms of skull have been met with in Belgium, the one in the famous cave of Chauvaux, the other in that of Sclaigneaux.

The first of these is a rock-shelter passing into a small cave, at the base of the limestone cliff on the Meuse, opposite the little village of Rivière, between Dinant and Namur. It was known to contain human remains in 1837–8, and was partially explored in 1842 by Dr. Spring, who published his account of the discoveries in 1853, and subsequently in 1864 and 1866. Below a thin layer of loam139 was a floor of stalagmite, concealing140 a vast number of broken human bones mixed pêle-mêle with those of wild and domestic animals, and associated with charcoal and coarse pottery. Two polished stone celts indicated the neolithic age of the accumulation; one of them resting close to a skull which had been fractured by a blow from a blunt instrument, such as it may have inflicted. The human bones belonged to infants and young adults.

From the fractured and burnt bones of the animals it is clear that they had been accumulated in the cave216 daring the time that it was inhabited by man. Dr. Spring136 inferred that the broken human bones proved that human beings, as well as the animals, formed the food of the cave-dwellers, and further, since all the human remains belong to young individuals, that the cannibalism was not accidental, or caused by famine, but the result of a deliberate selection.

The facts which induced Dr. Spring to come to this conclusion are interpreted by M. Dupont137 in a different manner. He holds, that the proportion of young individuals is not greater in Chauvaux than that which he has observed in other sepulchral caves in Belgium, and that there is nothing which forbids the supposition that this also was used as a place of interment. The human bones may have been broken by the foxes and badgers141, which are so abundant in the district, and have been mixed, by their continual burrowing, with the remains of the animals in the old refuse-heap accumulated on the floor during the habitation of man. Such a mixture of remains we have already observed in the caves of North Wales and Gibraltar. The recent researches of M. Soreil138 leave no room for doubting the truth of M. Dupont’s interpretation142. Two perfect human skeletons were discovered along with flint flakes, pottery, a barbed arrow-head, and many scattered human bones not broken by design, while the long bones of the associated animals bore unmistakeable217 traces of having been split for the sake of the marrow143. On one long bone, for example, of the ox, there were cuts made by a flint implement22, as well as the mark of the blow by which it had been split longitudinally; and another ox-bone, and the canine of a boar, bore marks of burning. The bones of the animals were very abundant, and belonged to the following species: beaver144, hamster, and other small rodents145, hare, badger, fox, boar, stag, roe, ox, and goat. In this case, as in the caves of Perthi-Chwareu, and of l’Homme Mort, the inhabitants had used the hare for food, as well as the other animals, and did not share the prejudice against the use of its flesh for food, which C?sar remarks of the inhabitants of Britain (Comm. 1, xii.).

The cave must, therefore, be viewed as a place of sepulture for a neolithic people, whose implements abound146 in the neighbourhood, and not as having been inhabited by a race of cannibals.

The bodies had been interred in the crouching147 posture, with their thighs148 bent149, their heads resting on their arms, and their faces turned towards the valley. They rested side by side in two small holes, which had been dug in the deposit containing the bones of the animals, and the skeletons were cemented to the rock by stalagmite, and surrounded by large stones. They belonged to individuals far past the prime of life.

Both skulls were dolicho-cephalic, and the most perfect of them is described by Professor Virchow as presenting a parietal flattening, which is probably analogous150 to the “tête annulaire,” so commonly present in the long skulls of the neolithic age. It possesses a cephalic index of ·72 (·718 Virchow). The sutures in both the skulls were very nearly obliterated151.218 The measurements are given in the Table in page 199.

The crania, in all these characters, are to be classified with the long skulls from the caves and chambered tombs of France, Britain, and Spain. They belong to people in the same stage of culture, and practising the same mode of burial in a crouching posture. Chauvaux is the furthest cave to the east on the continent of Europe, in which traces of this long-headed race have been observed.

The Cave of Sclaigneaux.

The cave of Sclaigneaux,139 explored by M. Arnould, near the hamlet of that name, fourteen miles from Namur, has been proved to contain human bones, lying mixed with those of the animals in the refuse-heap on the floor, as in the cave of Chauvaux. The animals belonged to existing species:—

Hedgehog.

Badger.

Beech-marten.

Weazel.

Fox.

Dog.

Wild Cat.

Hare.

Rabbit.

Ox.

Goat.

Stag.

Boar.

Horse.

Rodents.

Bones of birds, frogs, and fishes were also met with. Intermingled with these were human skeletons, disposed in a rude sort of order, and belonging to bodies which had been interred at different times. From the lower jaws152 M. Arnould calculates that the number of bodies interred was not less than sixty-two, of which twelve belonged to aged153 individuals, twenty-one to those in the prime of life, sixteen to young adults, and thirteen to children.

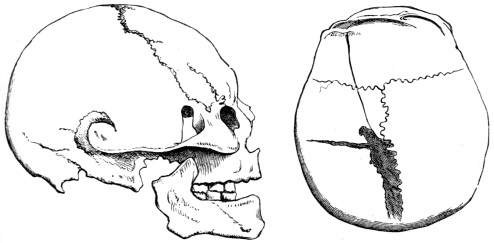

Figs. 65, 66.—Skull from Cave of Sclaigneaux. (Arnould.)

The crania (Figs. 65, 66) are brachy-cephalic (see Table, p. 199), and are possessed, according to M. Arnould, of the following characters. The apex154 of the cranial vault155 is flattened156, probably artificially, and the parietal bosses are largely developed, to which is due the great width of the skull. The surciliary ridges are strongly marked, and the malar bones are prominent. In all these particulars they agree with the broad skulls, as defined by Dr. Thurnam, discovered in the round tumuli of Britain and the sepulchral caves of France.

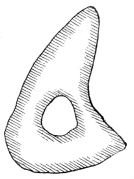

Fig. 67.—Platycnemic tibia, from Sclaigneaux.

Some of the leg-bones presented the antero-posterior flattening, or platycnemism, observed in the skeletons from the caves of Gibraltar, and in France and Great Britain (Fig. 67). It is due, as in those from North Wales, to the anterior157 expansion of the bone, and not to the posterior, as is the case with those from the cave of Cro-Magnon.

220 A beautifully chipped arrow-head, with barbs158 and central tongue for insertion into the shaft, of the same type as one from Chauvaux, implies that these remains belong to the neolithic age. Implements of bone, and a shell perforated for suspension, were also found.

The Evidence of History as to the Peoples of Gaul and Spain.

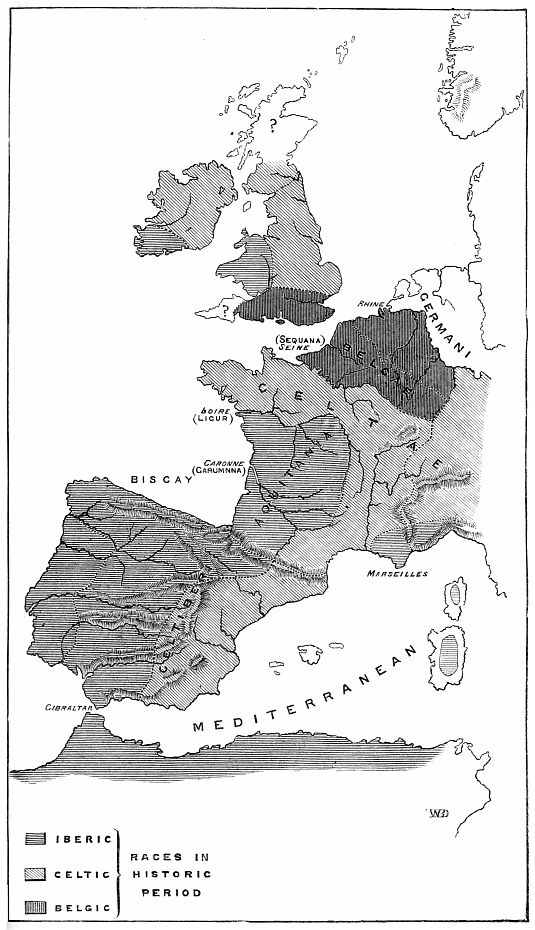

The extension of this non-Aryan race through France, Spain, and Britain, in ancient times, based solely159 on the evidence of the human remains, is confirmed by an appeal to the ethnology of Europe within the historic period. In the Iberian peninsula the Basque populations of the west are defined from the Celtic of the east by the Celtiberi inhabiting the modern Castille (see Map, Fig. 68). In Gaul the province of Aquitania extended as far north, in C?sar’s time,140 as the river Garonne, constituting the modern Gascony, to which was added, in the days of Augustus, the district between that river and the Loire; a change of frontier that was probably due to the predominance of Basque blood in a mixed race in that area similar to the Celtiberi of Castille. The Aquitani were surrounded on every side, except the south, by the Celt?, extending as far north as the Seine, as far to the east as Switzerland and the plains of Lombardy, and southwards, through the valley of the Rhone and the region of the Volc?, over the Eastern Pyrenees into Spain. The district round the Phoc?an colony of Marseilles was inhabited by Ligurian tribes, who held the region between the river Po and the Gulf160 of Genoa, as far as the western boundary of Etruria, and who probably221 extended to the west along the coast of Southern Gaul as far as the Pyrenees.141 They were distinguished from the Celt?, not merely by their manners and customs, but by their small stature and dark hair and eyes, and are stated by Pliny and Strabo to have inhabited Spain. They have also left marks of their presence in Central Gaul in the name of the Loire (Ligur), and possibly in Britain in the obscure name of the Lloegrians. They invaded Sicily142 as the Sikelians, and if the latter be identified with the Sikanians considered by Thucydides143 and other writers to be of Iberian stock, it will follow that they are a cognate race. Their stature and swarthy complexion161, as well as the ancient geographical position conterminous with the Iberic population of Gaul and Spain, confirm this conclusion. The non-Aryan and probably Basque population of Gaul was therefore cut into two portions by a broad band of Celts, which crosses the Eastern Pyrenees, and marks the route by which the Iberian peninsula was invaded.

Fig. 68.—Distribution of Basque, Celtic, and Belgic Peoples, at dawn of History.

The ancient population of Sardinia is stated by Pausanias to be of Libyan extraction, and to bear a strong resemblance to the Iberians in physique and in habits of life, while that of Corsica is described by Seneca as Ligurian and Iberian. The ancient Libyans are represented at the present day by the Berber and Kabyle tribes which are, if not identical with, at all events cognate with the Basques. We may therefore infer that223 these two islands were formerly162 occupied by this non-Aryan race, as well as the adjacent continents of Northern Africa and Southern Europe.

The Basque Population the Oldest.

The relative antiquity163 of these two races in Europe may be arrived at by this distribution. The Basques, Sikani or Ligurian, are the oldest inhabitants, in their respective districts, known to the historian; while the Celts appear as invaders, pressing southwards and westwards on the populations already in possession, flooding over the Alps and under Brennus sacking Rome, and by their union with the vanquished165 in Spain constituting the Celtiberi. We may therefore be tolerably certain that the Basques held France and Spain before the invasion of the Celts, and that the non-Aryan peoples were cut asunder166, and certain parts of them left—Ligurians, Sikani, and in part Sardinians and Corsicans—as ethnological islands, marking, so to speak, an ancient Basque non-Aryan continent which had been submerged by the Celtic populations advancing steadily167 westwards.

At the time of the Roman conquest of Gaul, the Belg? were pressing on the Celts, just as the latter pressed the Basques, the Seine and the Marne forming their southern boundary, and in their turn being pushed to the west by the advance of the Germans in the Rhine provinces. Thus we have the oldest population, or Basque, invaded by the Celts, the Celts by the Belg?, and these again by the Germans; their relative positions stamping their relative antiquity in Europe.

224

The Population of Britain.

The Celtic and Belgic invasion of Gaul repeated itself, as might be expected, in Britain. Just as the Celts pushed back the Iberian population of Gaul as far south as Aquitania, and swept round it into Spain, so they crossed over the Channel and overran the greater portion of Britain, until the Silures, identified by Tacitus144 with the Iberians, were left only in those fastnesses that formed subsequently a bulwark168 for the Brit-Welsh against the English invaders. And just as the Belg? pressed on the rear of the Celts as far as the Seine, so they followed them into Britain, and took possession of the “Pars Maritima,”145 or southern counties. The unsettled condition of the country at the time of C?sar’s invasion was, probably, due to the struggle then going on between Celts and Belg?.

The evidence offered by history as to the distribution of these races confirms that which has been arrived at by the examination of the caves and tumuli. In the one case the Basque peoples are merely known in a fragmentary condition in Britain, Gaul, and Sicily, while in the other those fragments are joined together in such a way as to show that, in the neolithic age, they extended uninterrupedly through Western Europe, from the Pillars of Hercules in the south to Scotland in the north, before they were dispossessed by their broad-headed enemies. It is impossible to define with precision their ethnological relation to the non-Aryan inhabitants of Italy and the coasts of the Mediterranean, such as the Etruscans and Tyrrhenians. I225 am, however, inclined to hold that they are all branches of the same race of “Melanochroi,” differing far less from each other than the Celtic from the Scandinavian branch of the Aryan family.146

Basque Element in present British and French Populations.

This non-Aryan blood is still to be traced in the dark-haired, black-eyed, small, oval-featured peoples in our own country in the region of the Silures, where the hills have afforded shelter to the Basque populations from the invaders.147 The small swarthy Welshman of Denbighshire is in every respect, except dress and language, identical with the Basque inhabitant of the Western Pyrenees, at Bagnères de Bigorre.

The small dark-haired people of Ireland,148 and especially those to the west of the Shannon, according to Dr. Thurnam and Professor Huxley, are also of Iberian derivation, and singularly enough there is a legendary169 connection between that island and Spain. The human remains from the chambered tombs as well as the riverbeds prove that the non-Aryan population spread over the whole of Ireland as well as the whole of Britain. The main mass of the Irish population is undoubtedly170 Celtic, crossed with Danish, Norse, and English blood.

226 The Basque element in the population of France is at the present time centered in the old province of Aquitaine, in which the jet-black hair and eyes, and swarthy complexion, strike the eye of the traveller, now as in the days of Strabo,149 and form a vivid contrast with the brown hair and grey eyes of the inhabitants of Celtica and Belgica (see Map, Fig. 68). If Fig. 68 be compared with the map published by Dr. Broca (“Mémoires d’Anthropologie,” t. i. p. 330), which shows at a glance the average complexion prevailing171 in each department, and the relative number of exemptions172 per 1,000 conscripts, on account of their not coming up to the standard of height (1·56 metre = 5 feet 1? inches), it will be seen that the only swarthy people outside the boundary of Aquitaine constitute five ethnological islands. Of these Brittany is by far the largest, probably because its fastnesses afforded a shelter to the Basques, who were being driven to the south-west. The department of the Meuse, in the north, and those of Tarn173 and Arriège, in the south, are also sundered174 from the main body, while those of the Upper and Lower Alps present us with the descendants of the ancient Ligurian tribes.

The people with dark-brown hair, considered by Dr. Broca to be the result of the intermingling of a dark with a fair race, are scattered about through Aquitaine, and occur only in two departments in northern Celtica. The fair people, on the other hand, are massed in northern Celtica and Belgica. The relation of complexion to227 stature may be gathered from the following table of exemptions per 1,000 for each department:—

Départements noirs 98·5 to 189??

” gris-foncés 64·? ” ?97??

” gris-clairs 48·8 ” ?63·8

” blancs-clairs 23·? ” ?48·5

From this table it is evident that the swarthy people are the smallest and the fair the tallest, the intermediate shades being the result of fusion between the two extremes.

The distribution therefore of the small swarthy Basque, and tall fair Celtic and Belgic races in France at the present time, corresponds essentially175 with that which we might have expected from the evidence both of history and of the neolithic caves and tombs.150

When we consider the many invasions of France, and the oscillations to and fro of peoples, the persistence176 of the Basque population is very remarkable. It is not a little strange that the type should be so slightly altered by intermarriage with the conquering races.

Whence came the Basques?

From what region did the Basques invade Europe? M. Broca, from their identity with the Kabyles and Berbers, holds that they entered Europe from northern228 Africa, spreading over Spain, and passing over the Pyrenees into southern France. It seems, however, to me, from their range as far north as Scotland, and at least as far to the east as Belgium, that they travelled by the same route that the Celtic, Belgic, and Germanic tribes travelled long ages afterwards, coming from the east and pushing their way to the west: and that while one section chose this route, another mastered northern Africa, following the same westward164 direction as the Saracens. On this hypothesis this great pre-Aryan migration177 would start from the central plateau of Asia, from which all the successive invaders of Europe have swarmed178 off.

This view of the eastern derivation of the Basque peoples is confirmed by the examination of the breeds of domestic animals which they possessed. The Bos longifrons, the sheep, and the goat are derived179 from wild stocks that are now to be found only in central Asia; and the dog and breed of swine with small canines180 were also probably imported after they had become the servants of man in the east.151

The Celtic and Belgic Brachy-cephali.

The occurrence of broad-skulls in the tumuli in this country, and in caves and tumuli in France, proves that the Basque peoples were invaded during the neolithic229 age. And since Dr. Thurnam has shown that they are identical in form with Celtic and Belgic skulls,152 it follows that one or the other of these, probably the Celtic or the older, was in possession of portions of Britain, Ireland, and Gaul at that remote time. It is of course conceivable that non-Celtic races, physically181 allied to the Celts or Belg?, are represented by the human remains in question; but in that case they have left no mark behind by which they can be identified. And the supposition is rendered improbable to the last degree by the fact, that the older or conquered race—the Basque—still survives, in the area under consideration, the invasions and vicissitudes182 which it has undergone. A fortiori, would their conquerors183 have had a still greater chance of survival, in the fastnesses which are offered by these countries. It is therefore reasonable to presume that the broad-headed peoples in the neolithic caves and tombs are represented by the Celts, and possibly, though not probably, in part by the Belg?, rather than by the equally broad-headed Wends, Sclavonians, and Fins184, which are not known by the historian to have settled in Gaul or in Britain. The successive invasions of Europe have been invariably from the east to the west, so far as we have any certain knowledge; and it is most improbable that Wends, Fins, or Sclaves should have occupied these countries and subsequently have retreated eastwards185 against the current of the Celtic, Belgic, and Germanic invasions.

The Celt? may, therefore, be inferred to have occupied Gaul and Britain in the ages of polished stone, bronze, and of iron, their encroachment186 on the non-Aryan peoples being regulated by their strength, and the amount of230 pressure on their rear. The Belg? probably were not known in Gaul until the later portion of the iron age, and were of small importance as compared with the Celts, whose arms were felt alike in Greece, Italy, Spain, and Asia Minor187.

The Celts were a tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed race (Xanthochroi), contrasting strongly with the Basque “Melanochroi”, and in those particulars agreeing with the Germans.153

The Ancient German Race.

The Germans, in the days of C?sar, were advancing on the Belg? in the Rhine provinces, and on the Helvetii in Switzerland, and are recognized by Tacitus,154 in Britain as the red-haired, tall inhabitants of Caledonia. Subsequently they spread over the west and south of Europe, as Goths, Franks, Scandinavians, English and Normans; in this country sweeping the Brit-Welsh into the hilly fastnesses of Wales, making settlements on many points of the coasts of Ireland, and leaving behind them, to this day, a considerable infusion of German blood in the Celtic and Basque populations. They were, unlike the present inhabitants of North Prussia and southern and middle Germany, a dolicho-cephalic people, their length of head being due, according to Gratiolet, to a frontal instead of an occipital development, which causes the long-headedness of the Basques. The Anglo-Saxon skull is defined by Dr. Thurnam as prognathous, with large facial bones, and with a cephalic index231 averaging ·75. And these characters are equally to be found in the Gothic, Frankish, and Scandinavian crania.

General Conclusions.

In this outline of the ethnology of Gaul and Britain, it will be seen that two out of the three ethnical elements (if the Belgic be classed with the Celtic), of which the present population is composed, can be recognized in the neolithic users of caves and builders of chambered tombs. A non-Aryan race either identical or cognate with the Basque is the earliest traceable in these areas in the neolithic age, and it probably arrived in Europe by the same route as the Celtic and Germanic, passing westwards from the plains of central Asia.

There is no evidence of Spain having been peopled from northern Africa, the identity of the Berber and Kabyle with the Basque being due to their being descended188 from the same non-Aryan stock in possession of southern and western Europe, and northern Africa. They are to be looked upon as cousins rather than as connected by descent in a right line.

The Basque race was probably in possession of Europe for a long series of ages, before hordes189 either identical or cognate with the Celts gradually crept westward over Germany into Gaul, Spain, and Britain, driving away, or absorbing, the inhabitants of the regions which they conquered.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

neolithic

|

|

| adj.新石器时代的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

cavern

|

|

| n.洞穴,大山洞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

sepulchral

|

|

| adj.坟墓的,阴深的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

isles

|

|

| 岛( isle的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

cognate

|

|

| adj.同类的,同源的,同族的;n.同家族的人,同源词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

terminology

|

|

| n.术语;专有名词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

skull

|

|

| n.头骨;颅骨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

unity

|

|

| n.团结,联合,统一;和睦,协调 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

skulls

|

|

| 颅骨( skull的名词复数 ); 脑袋; 脑子; 脑瓜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

asymmetry

|

|

| n.不对称;adj.不对称的,不对等的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

pointed

|

|

| adj.尖的,直截了当的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

prehistoric

|

|

| adj.(有记载的)历史以前的,史前的,古老的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

hog

|

|

| n.猪;馋嘴贪吃的人;vt.把…占为己有,独占 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

confinement

|

|

| n.幽禁,拘留,监禁;分娩;限制,局限 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

justify

|

|

| vt.证明…正当(或有理),为…辩护 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

sweeping

|

|

| adj.范围广大的,一扫无遗的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

inquiry

|

|

| n.打听,询问,调查,查问 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

chamber

|

|

| n.房间,寝室;会议厅;议院;会所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

implements

|

|

| n.工具( implement的名词复数 );家具;手段;[法律]履行(契约等)v.实现( implement的第三人称单数 );执行;贯彻;使生效 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

implement

|

|

| n.(pl.)工具,器具;vt.实行,实施,执行 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

dominant

|

|

| adj.支配的,统治的;占优势的;显性的;n.主因,要素,主要的人(或物);显性基因 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

reign

|

|

| n.统治时期,统治,支配,盛行;v.占优势 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

receding

|

|

| v.逐渐远离( recede的现在分词 );向后倾斜;自原处后退或避开别人的注视;尤指问题 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

backwards

|

|

| adv.往回地,向原处,倒,相反,前后倒置地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

vertical

|

|

| adj.垂直的,顶点的,纵向的;n.垂直物,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

possessed

|

|

| adj.疯狂的;拥有的,占有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

ridges

|

|

| n.脊( ridge的名词复数 );山脊;脊状突起;大气层的)高压脊 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

ridge

|

|

| n.山脊;鼻梁;分水岭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

savageness

|

|

| 天然,野蛮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

rev

|

|

| v.发动机旋转,加快速度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

jaw

|

|

| n.颚,颌,说教,流言蜚语;v.喋喋不休,教训 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

sockets

|

|

| n.套接字,使应用程序能够读写与收发通讯协定(protocol)与资料的程序( Socket的名词复数 );孔( socket的名词复数 );(电器上的)插口;托座;凹穴 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

canine

|

|

| adj.犬的,犬科的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

annular

|

|

| adj.环状的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

distinguished

|

|

| adj.卓越的,杰出的,著名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

stature

|

|

| n.(高度)水平,(高度)境界,身高,身材 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

oblique

|

|

| adj.斜的,倾斜的,无诚意的,不坦率的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

flattening

|

|

| n. 修平 动词flatten的现在分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

infancy

|

|

| n.婴儿期;幼年期;初期 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

apparatus

|

|

| n.装置,器械;器具,设备 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

allied

|

|

| adj.协约国的;同盟国的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

Oxford

|

|

| n.牛津(英国城市) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

pottery

|

|

| n.陶器,陶器场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

charcoal

|

|

| n.炭,木炭,生物炭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

badger

|

|

| v.一再烦扰,一再要求,纠缠 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

gnawed

|

|

| 咬( gnaw的过去式和过去分词 ); (长时间) 折磨某人; (使)苦恼; (长时间)危害某事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

roe

|

|

| n.鱼卵;獐鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

flakes

|

|

| 小薄片( flake的名词复数 ); (尤指)碎片; 雪花; 古怪的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

ware

|

|

| n.(常用复数)商品,货物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

alluvial

|

|

| adj.冲积的;淤积的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

mound

|

|

| n.土墩,堤,小山;v.筑堤,用土堆防卫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

dwelling

|

|

| n.住宅,住所,寓所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

lesser

|

|

| adj.次要的,较小的;adv.较小地,较少地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

cormorant

|

|

| n.鸬鹚,贪婪的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

cod

|

|

| n.鳕鱼;v.愚弄;哄骗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

lobster

|

|

| n.龙虾,龙虾肉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

reindeer

|

|

| n.驯鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

chambers

|

|

| n.房间( chamber的名词复数 );(议会的)议院;卧室;会议厅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

mere

|

|

| adj.纯粹的;仅仅,只不过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

fusion

|

|

| n.溶化;熔解;熔化状态,熔和;熔接 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

solitary

|

|

| adj.孤独的,独立的,荒凉的;n.隐士 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

anthropological

|

|

| adj.人类学的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

latitudinal

|

|

| adj.纬度的,纬度方向的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

situated

|

|

| adj.坐落在...的,处于某种境地的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

penetrates

|

|

| v.穿过( penetrate的第三人称单数 );刺入;了解;渗透 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

limestone

|

|

| n.石灰石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

partially

|

|

| adv.部分地,从某些方面讲 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

mingled

|

|

| 混合,混入( mingle的过去式和过去分词 ); 混进,与…交往[联系] | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

hearths

|

|

| 壁炉前的地板,炉床,壁炉边( hearth的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

stump

|

|

| n.残株,烟蒂,讲演台;v.砍断,蹒跚而走 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

abruptly

|

|

| adv.突然地,出其不意地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

scattered

|

|

| adj.分散的,稀疏的;散步的;疏疏落落的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

disturbance

|

|

| n.动乱,骚动;打扰,干扰;(身心)失调 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

burrowing

|

|

| v.挖掘(洞穴),挖洞( burrow的现在分词 );翻寻 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

cannibalism

|

|

| n.同类相食;吃人肉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

delicacy

|

|

| n.精致,细微,微妙,精良;美味,佳肴 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

abode

|

|

| n.住处,住所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

interred

|

|

| v.埋,葬( inter的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

hybrid

|

|

| n.(动,植)杂种,混合物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

intersection

|

|

| n.交集,十字路口,交叉点;[计算机] 交集 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

lobes

|

|

| n.耳垂( lobe的名词复数 );(器官的)叶;肺叶;脑叶 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

geographical

|

|

| adj.地理的;地区(性)的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

fissure

|

|

| n.裂缝;裂伤 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

decomposed

|

|

| 已分解的,已腐烂的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

shaft

|

|

| n.(工具的)柄,杆状物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

penetrated

|

|

| adj. 击穿的,鞭辟入里的 动词penetrate的过去式和过去分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

spotted

|

|

| adj.有斑点的,斑纹的,弄污了的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

rhinoceros

|

|

| n.犀牛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

marine

|

|

| adj.海的;海生的;航海的;海事的;n.水兵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

vessels

|

|

| n.血管( vessel的名词复数 );船;容器;(具有特殊品质或接受特殊品质的)人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

spouts

|

|

| n.管口( spout的名词复数 );(喷出的)水柱;(容器的)嘴;在困难中v.(指液体)喷出( spout的第三人称单数 );滔滔不绝地讲;喋喋不休地说;喷水 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

lathe

|

|

| n.车床,陶器,镟床 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

metallic

|

|

| adj.金属的;金属制的;含金属的;产金属的;像金属的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

spikes

|

|

| n.穗( spike的名词复数 );跑鞋;(防滑)鞋钉;尖状物v.加烈酒于( spike的第三人称单数 );偷偷地给某人的饮料加入(更多)酒精( 或药物);把尖状物钉入;打乱某人的计划 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

inflicted

|

|

| 把…强加给,使承受,遭受( inflict的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

chisel

|

|

| n.凿子;v.用凿子刻,雕,凿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

alabaster

|

|

| adj.雪白的;n.雪花石膏;条纹大理石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

ornament

|

|

| v.装饰,美化;n.装饰,装饰物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

lateral

|

|

| adj.侧面的,旁边的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

figs

|

|

| figures 数字,图形,外形 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

determined

|

|

| adj.坚定的;有决心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

considerably

|

|

| adv.极大地;相当大地;在很大程度上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

elongated

|

|

| v.延长,加长( elongate的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

copper

|

|

| n.铜;铜币;铜器;adj.铜(制)的;(紫)铜色的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

caverns

|

|

| 大山洞,大洞穴( cavern的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

pervaded

|

|

| v.遍及,弥漫( pervade的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

antiquities

|

|

| n.古老( antiquity的名词复数 );古迹;古人们;古代的风俗习惯 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

adorned

|

|

| [计]被修饰的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

tunic

|

|

| n.束腰外衣 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

ornaments

|

|

| n.装饰( ornament的名词复数 );点缀;装饰品;首饰v.装饰,点缀,美化( ornament的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

tusk

|

|

| n.獠牙,长牙,象牙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

earrings

|

|

| n.耳环( earring的名词复数 );耳坠子 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

derives

|

|

| v.得到( derive的第三人称单数 );(从…中)得到获得;源于;(从…中)提取 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

extremity

|

|

| n.末端,尽头;尽力;终极;极度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

ERECTED

|

|

| adj. 直立的,竖立的,笔直的 vt. 使 ... 直立,建立 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

erecting

|

|

| v.使直立,竖起( erect的现在分词 );建立 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

excavated

|

|

| v.挖掘( excavate的过去式和过去分词 );开凿;挖出;发掘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

125

niches

|

|

| 壁龛( niche的名词复数 ); 合适的位置[工作等]; (产品的)商机; 生态位(一个生物所占据的生境的最小单位) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

126

clan

|

|

| n.氏族,部落,宗族,家族,宗派 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

127

concealed

|

|

| a.隐藏的,隐蔽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

128

thoroughly

|

|

| adv.完全地,彻底地,十足地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

129

posture

|

|

| n.姿势,姿态,心态,态度;v.作出某种姿势 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

130

barley

|

|

| n.大麦,大麦粒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

131

beads

|

|

| n.(空心)小珠子( bead的名词复数 );水珠;珠子项链 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

132

insulation

|

|

| n.隔离;绝缘;隔热 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

133

Mediterranean

|

|

| adj.地中海的;地中海沿岸的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

134

akin

|

|

| adj.同族的,类似的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

135

cemetery

|