It is evident, from the scanty5 remains found in caves, that they were not the normal habitations of men in the Bronze or Iron stages of culture. We shall, however, find that they were used by the neolithic peoples, both for shelter and for burial, in nearly every portion of Europe which has been explored.

Neolithic Caves in Great Britain.—Perthi-Chwareu.

The most remarkable6 examples of caves, turned to both these uses, in Britain, are offered by the group clustering round a refuse-heap at Perthi-Chwareu, a farm high up in the Welsh hills, about ten miles to the east of Corwen, and a mile to the west of the little village of Llandegla, in Denbighshire.

150

The Refuse-heap.

The first intimation of any prehistoric7 remains in that locality was afforded by a small box of bones forwarded to me by Mr. Darwin, in 1869; and this I was able to follow up, through the kind assistance of Mrs. Lloyd, the owner of the property on which they were found, from time to time, during 1869–70–71–2. The mountain limestone9, which there forms hill and valley, consists of thick masses of hard rock, separated by soft beds of shale10, and contains large quantities of producti, crinoids and corals. The strata11 dip to the south, at an angle of about 1 in 25, and form two parallel ridges12, with abrupt14 faces to the north, and separated from each other by a narrow valley, passing east and west along the strike. The remains sent by Mr. Darwin were obtained from a space between two strata near the top of the northern ridge13, whence the intervening softer material had been carried away by water. Its maximum height was 6 inches, and its width 20 feet or more; and it extended in a direction parallel to the bed of the rocks. The bones, which had evidently been washed in by the rain, and not carried in by any carnivora, belong to the following species:—

Canis familiaris—The Dog.

Canis vulpes—The Fox.

Meles taxus—The Badger15.

Sus scrofa—The Pig.

Cervus capreolus—The Roe16-deer.

Cervus elaphus—The Red-deer.

Capra hircus—The Goat.

Bos longifrons—The Celtic Short-horn.

Equus caballus—The Horse.

Arvicola amphibius—The Water-rat.

Lepus timidus—The Hare.

Lepus cuniculus—The Rabbit.

The Eagle.

151 Nearly all the bones were broken, and belonged to young animals. Those of the Celtic short-horn, of the sheep or goat, and of the young pig, were very abundant; while those of the roe and stag, hare and horse, were comparatively rare. The remains of the domestic dog were rather abundant, and the percentage of young puppies implies also that they, like the other animals, had been used for food. Possibly the hare may also have been eaten, but its remains were scarce, and belonged to adults. Some of the bones had been gnawed17 by dogs. The only reasonable cause that can be assigned for the accumulation of the remains of these animals is, that the locality was inhabited by men of pastoral habits, but yet to a certain extent dependent on the chase, and that the relics18 of their food were thrown out to form a refuse-heap. The latter had altogether disappeared from the surface of the ground, from the action of the rain and other atmospheric19 causes, while those portions of it which chanced to be washed into the narrow interspace between the strata were preserved, to mark the spot which it once occupied.

There was nothing in the deposit that fixes the date of its accumulation. It may have been of the stone, bronze, or iron age; but from the presence of the goat, short-horned ox, and dog, it certainly does not date so far back as the epoch20 of the reindeer21, mammoth22, rhinoceros23, and cave-hy?na. The presence of the Celtic short-horn throws no light upon the antiquity24, because for centuries after it had ceased to be the domestic breed in England it remained in Wales, and still lives in the small black Welsh cattle, that are lineal descendants of those which furnished beef to the Roman provincials25 in Britain.

152

The Sepulchral Caves.

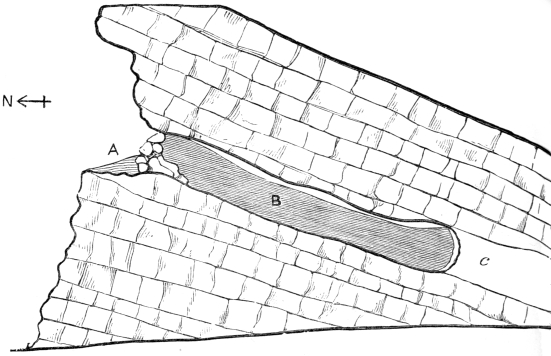

Fig26. 36.—Section of Cave at Perthi-Chwareu. Scale 12 feet to 1 inch.

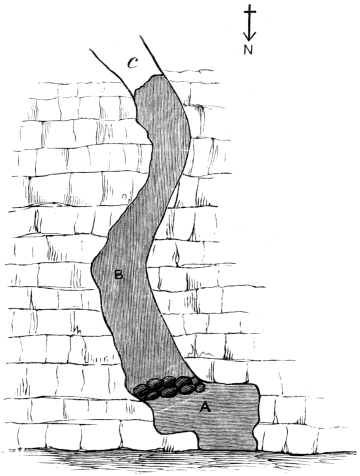

While the refuse-heap was being explored, I chose a small depression (Fig. 36 A) in the precipitous side of the southern ridge, that formed a kind of rock shelter overlooking the valley, and that seemed to be a likely place for the abode27 of man, or of wild animals. On setting the men to work, in a few minutes we began to discover the remains of dog, marten-cat, fox, badger, goat, Celtic short-horn, roe-deer and stag, horse, and large birds. Mixed with these, as we proceeded, we began to find human bones, between and underneath28 large masses of rock, that were completely covered up with red silt29 and sand. As these were cleared away, we gradually realized that we were on the threshold of a sepulchral cave. In the small space then excavated30, human remains, belonging to no fewer than five individuals, were found. Subsequently153 the work was carried on by Mrs. Lloyd, under the careful supervision31 of her agent Mr. Reid. The rock-shelter narrowed into a “tunnel cave,” that penetrated32 the rocks in a line parallel to the bedding, and, roughly speaking, at right angles to the valley, having a width varying from 3 feet 4 inches to 5 feet 6 inches, and a height from 3 feet 4 inches to 4 feet 6 inches.

The entrance was completely blocked up with red earth and loose stones, the latter, apparently33, having been placed there by design (Figs34. 36, 37). The inside of the cave was filled with red earth and sand to within about a foot of the roof. The remains were found, for the most part, on or near the top; but in some cases they were deep down. One human skull35, for example, was found six inches only above the rocky floor. The human bones were associated with those of the animals of which a list has been given, and occurred in little confused heaps. One human femur was in a perpendicular36 position. The account of the continuation of the digging is given almost in the words of Mrs. Lloyd. On the second day, after an hour’s work, a human skull was found near the roof of the cave, resting on a femur; then eleven feet explored brought to light a large quantity of human bones, including nine femurs. The third and fourth days were devoted37 to clearing out the cave (Fig. 36–7 B) up to this point, and to excavating38 about four feet further in, or fifteen from the entrance. During the work two teeth of a horse were found, resting on the floor near the entrance, and nine more about ten feet within the cave; also a boar’s tusk39 of remarkable size, and close by a mussel and cockle-shell, and valve of Mya truncata, along with a quantity of human and other bones; including five skulls40, more or less perfect,154 and many fragments. All these skulls were found between the tenth and fifteenth feet from the entrance. During the fifth and sixth days, the work was superintended by Mr. Reid, who entirely41 cleared the cave for about thirteen feet further: the first eight feet yielded a small quantity of human and other bones, including the perfect skull of a marten-cat and the incisor of a wild boar. The only implement42 found in the cave, a broken flint flake43, occurred here, and a nearly perfect human skull, lying face downwards44, with the pelvis adhering to one side. The last five feet furnished only two bones, both of the short-horned ox. The end of the cave was composed of unproductive grey clay. (Figs. 36–7 C.)

Fig. 37.—Plan of Cave at Perthi-Chwareu.

155 Small fragments of charcoal45 occurred throughout the cave, and a great many rounded pebbles46 from the boulder48 clay of the neighbourhood.

The human remains belong for the most part to very young or adolescent individuals, from the small infant to youths of twenty-one. Some, however, belong to men in the prime of life. All the teeth that had been used were ground perfectly49 flat. The skulls belong to that type which Professor Huxley terms the “river-bed skull.” Some of the tibi? present the peculiar50 flattening52 parallel to the median line, which Professor Busk denotes by the term platycnemic, and some of the femora were traversed by a largely developed and prominent linea aspera; but these peculiarities53 were not seen on all the femora and tibi?, and cannot therefore be considered characteristic of race, but most probably of sex. They were not presented by any of the younger bones.

All the human remains had undoubtedly54 been buried in the cave, since the bones were in the main perfect, or only broken by the large stones which had subsequently fallen from the roof. From the juxtaposition55 of one skull to a pelvis, and the vertical56 position of one of the femora, as well as the fact that the bones lay in confused heaps, it is clear that the corpses57 had been buried in the contracted posture58, as is usually the case in neolithic interments. And since the area was insufficient59 for the accommodation of so many bodies at one time, it is certain that the cave had been used as a cemetery60 at different times. The stones blocking up the entrance were probably placed as a barrier against the inroads of wild beasts.

These remains are the first in this country which present the peculiar character of platycnemism, noticed156 by Professor Busk and Dr. Falconer in human remains in the caves of Gibraltar, and by Dr. Broca in some of those from the dolmens of France, and subsequently in the celebrated61 skeletons found in the cave of Cro-magnon. I have also observed the same peculiar flattening of the tibia in the only fragment of human bone obtained by Mr. Foote, in the Lateritic deposits of the eastern coast of Southern India, along with the stone implements62 figured in the Norwich Volume of the International Congress of Prehistoric Arch?ology (1868, p. 224).

The remains of the animals associated with the human bones belong to the same species as those mentioned above from the débris of a refuse-heap, and are in a similar broken and split condition. They may have been deposited at the same time as the human skeletons, but, from the fact that some of them are gnawed by dogs, it is most probable that they were accumulated while the cave was used as a dwelling63. If the bodies were placed on an old floor of occupation, and afterwards disturbed by rabbits and badgers64, the remains would be mingled65 together as they were found to be mingled. The contents had evidently been disturbed by the burrowing66 of all these animals.

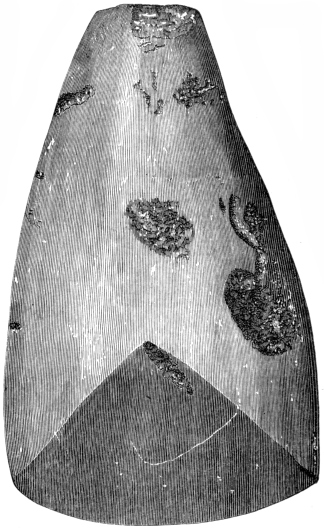

Subsequently we discovered and explored no less than four other sepulchral caves, within a few hundred yards of the refuse-heap, in which the corpses had been buried in the same crouching67 posture. From one on the farm of Rhosdigre we obtained a perfect celt of polished greenstone which had never been used (Fig. 38), together with several flint flakes68, and numerous fragments of pottery69, rude, black inside, hand-made, and containing in their substance small fragments of limestone.

157 Similar potsherds are preserved in the Oxford70 Museum, from the superficial deposits of the caves of Gailenreuth and Kuhlock, and I have observed them also among the remains from Kent’s Hole. The celt was most probably, from its unworn condition, buried with the dead, and it stamps the neolithic age of the interments of the whole group.

Fig. 38.—Greenstone Celt, Rhosdigre Cave. (Nat. size.)

Among the broken bones from this cave were the teeth of the brown bear, and the lower jaw71 of a wolf; and the fractured bones of the dog implied that that animal158 ministered to the appetite, as well as obeyed the commands, of the neolithic inhabitants. I have met with similar evidence of the use of dog’s flesh for food among the broken bones which Canon Greenwell obtained from the neolithic tumuli of the Yorkshire Wolds. On the other hand, the marks of the teeth of dogs, or wolves, on some of the human femora, implied that those animals made their way into this cave and feasted on the corpses.

The neolithic age of these interments is proved, not merely by the presence of the stone axe73, or of the flint flakes, but by the burial in a contracted posture,97 and the fact that the skulls are identical with those obtained from chambered tombs in the south of England proved to be neolithic by Dr. Thurnam.

The number of skeletons of all ages, and of both sexes, buried in these caves was very considerable; and they had been placed on the old floor of occupation at successive times. In that of Rhosdigre the accumulation of charcoal, broken bones, and fragments of pottery below some of the human skeletons, proved that it had been used for a habitation before it was used for a burial-place. It is very probable that originally the head of a family, or a clan74, or a tribe, was buried in his own cave-dwelling, and that it was afterwards used as a cemetery for his blood relations and followers75.

159

The Neolithic Caves in the neighbourhood of Cefn, near St. Asaph.

The same class of remains, referable to the neolithic age, have been met with in the caves in the limestone cliffs of the beautiful valleys of the Clwyd and the Elwy, near St. Asaph. In the collection of fossil bones in the possession of Mrs. Williams Wynn, discovered in 1833, in a cave at Cefn, by Mr. Edward Lloyd,98 is a human skull and lower jaw, along with platycnemic limb-bones. They were found mingled with the bones of goat, pig, fox, and badger, and cut antlers of the red-deer, inside the lower entrance of the cave, in which the extinct pleistocene animals were found in the valley of the Elwy. Four flint flakes also were discovered along with them.

The skull in its general features strongly resembles those found in the group of caves at Perthi-Chwareu, and presents a cephalic index99 of ·770, which comes within the limits of the extreme forms from that locality. Professor Busk, however, as will be seen in his account of this skull, because of its low altitudinal index—·702, as compared with ·710 of the lowest Perthi-Chwareu skull—is inclined to view it as of a different type. The conditions, on the other hand, under which it was found appear to me to be circumstantial evidence that the interment is of the same relative age as that of Perthi-Chwareu. Both were in caves: in both the remains of the same domestic and wild animals were found in the same fragmentary condition. Flint flakes also occurred in both; and what is more important, the platycnemic160 limb-bones in both imply a somewhat similar mode of life in the people to whom they belonged. This body of evidence, in favour of the interments having been made by the same race of men who lived some time in Denbighshire, seems to me of greater weight than that to the contrary afforded by the difference of ·008 in the altitudinal indices of the skulls. After a comparison of the carefully prepared measurements of the crania published in the “Crania Britannica” with those published elsewhere, I cannot resist the conviction, that if similar modes of life and of burial in Britain imply an identity of race, cranial variation within the limits of that race is by no means very small. Absolute purity of blood in an island so near the Continent as Britain cannot be looked for; and unity77 of type resulting from isolation78 from other races, such as that presented by the Australians, is not likely to be met with. It is therefore very probable that some of the variations may be accounted for by the blending of different ethnical elements in one race. I am consequently inclined to view the interments in these two caves as having been made by the same people, in spite of the small cranial difference manifested by the Cefn skull.

The cave in Brysgill, a small ravine leading into the valley of the Elwy, explored by Mr. Mainwaring and Mrs. Williams Wynn in 1871, furnished evidence of the occupation of man, probably of the neolithic age. From a dark layer composed of loam79, black with fragments of charcoal, a flint arrow-head, a core, a flake, and broken bones of the horse, Bos longifrons, goat, and dog, were obtained, as well as a few human bones which had not been broken by design.

The excavations80 carried on in the small tunnel-cave of Plas-Heaton, by Mr. Heaton and Professor Hughes,161 have shown that it was inhabited at two different ages. In the upper or prehistoric stratum81 were broken bones of the dog, badger, goat, Bos longifrons, and stag; while in the lower, or pleistocene, were the remains of the hy?na, reindeer, cave-bear, and the lower jaw of the glutton82.

The Chambered Tomb near Cefn, St. Asaph.

While the caves at Perthi-Chwareu were being explored, the accidental discovery of human remains in the cairn of Tyddyn Bleiddyn, near Cefn, St. Asaph, in 1869, led to a systematic83 examination of its contents by Mrs. Williams Wynn, under the superintendence of the Rev84. D. R. Thomas, myself, and the Rev. H. H. Winwood, which has resulted in the proof, that the people who buried their dead in caves used stone-chambered tombs for the same purpose.

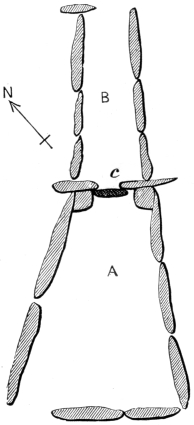

The cairn of loose fragments of limestone had been removed for road-mending before the cap-stones of the stone chamber3 were exposed, and these were broken before any scientific observation was made. The Rev. D. R. Thomas, however, rescued many of the human remains from destruction, and began the exploration which defined the extent of the chamber A (Fig. 39).

Fig. 39.—Plain of Chambered Tomb at Cefn.

Subsequently it was resumed in my presence, and the chamber A (Fig. 39) fully76 cleared out. At the point c it was partially85 shut off from the passage B by a slab86 of stone 18 inches high. The passage led from the chamber in a northern direction, and was 6 feet long by 2 wide. The chamber gradually narrowed towards the passage, being 5 feet wide at its broad end, and 9 feet long. In the passage, as well as in the chamber,162 there were human bones belonging to individuals who had been buried in a crouching posture. Unfortunately, as the remains have been scattered87, it is impossible to ascertain88 the exact number of the burials. I have, however, restored one skull and examined seven frontal bones, and other remains, which indicate that there were at least twelve persons, varying in age from infancy89 to full prime, buried in this tomb. In addition to these, there is a large box of bones in the possession of the Rev. D. R. Thomas, as well as other remains in other hands. But although the exact number of bodies interred90 cannot be made out, there is full proof that there were too many to have been deposited at one time in so small a cubic area; and therefore they must have been deposited at different times, as in the caves at Perthi-Chwareu. There were no remains of either wild or domestic animals; and the only foreign object was a small slightly chipped flint pebble47. From the remarkable conformation of the nasal bones of some of the skulls, it would seem likely that the burial-place belonged to one family; but, for a reason (see Notes on Human Remains, p. 183) stated by Professor Busk, this is by no means a certain inference.

The plan of the chamber and passage corresponds with that of the long barrow of West Kennet, figured in the “Crania Britannica,” and with that of the cromlech163 of Le Creux des Fées, Guernsey, described by Lieutenant91 Oliver.100 In the former of these the corpses were buried in a contracted posture, along with flint scrapers and fragments of rude pottery. In the latter the original contents have disappeared. To speak in general terms, the chamber and passage belong to the class of tombs which Dr. Thurnam names “Long Barrows,” and Professor Nilsson “Ganggr?ben,” and which are found in Scandinavia and France, as well as in Britain. And it is worthy92 of note that the partial insulation93 of the chamber A (Fig. 39) from the passage B by a slab (c), which does not reach up to the height of the walls, is to be seen in similar tombs both in Guernsey and in Brittany.

A second and larger chamber, composed of cave slabs94 of limestone, was discovered in the same cairn in 1871 by the Rev. D. R. Thomas, and completely excavated by him along with myself and the Rev. H. H. Winwood. It was of a rudely triangular95 form, 10 feet long by 6 wide, traversed by a partition of slabs, and provided with a narrow passage 10 feet long by 2 feet 6 in width, opening to the north, and fenced off completely from the chamber by a slab, as in the preceding case. Both the chamber and the passage were full of human remains of all ages, buried in a contracted posture; the number of interments being far too great to have allowed the bodies to have been deposited at one time. From the former I identified the broken jaw of a roebuck and remains of goat, a broken flint, and round pebbles of quartz97, while in the latter there were the teeth and bones of the dog and the pig.

164 Some of the tibi? from both the chambers98 were platycnemic, but that character was only to be recognized in the older bones. The skulls, from the second of the two chambers, agree so exactly with those from the caves, that it is not necessary to add to the table of measurements which Professor Busk has drawn99 up (p. 171).

Correlation100 of Chambered Tomb with Interments in the Caves of Perthi-Chwareu and Cefn.

Nor are we without evidence that the builders of this cairn belonged to the same race as those who buried their dead in the caves of Perthi-Chwareu and of Cefn. The crania and the limb-bones are identical, and in both the tombs and caves the dead were buried in a contracted posture.

Why then, it may be asked, were the remains of animals so rare in the one and so abundant in the other? In my opinion this difference may be explained by the hypothesis, invented by Professor Nilsson, of the origin of chambered tombs.101 The idea of the “gallery graves,” according to that high authority, was derived101 from the subterranean102 house in which the deceased lived, and in which he was buried after his death, after the fashion of the Eskimos at the present day. The plan of the houses, like that of the ancient Lycian dwellings103 described by Sir Charles Fellowes, was preserved in the tombs, and probably for many ages after houses were no longer made in that fashion; since the principle of conservatism and the force of custom are more deeply165 rooted in religious and solemn ceremonial than in the changes of every-day life.

The rarity of the remains of the animals may be explained by the fact of these tombs never having been used as dwellings, while their abundance in the caves may be accounted for by the latter having been inhabited by man, and thus the idea of the dead resting in his own house would be the cause of burial both in caves and chambered tombs. It is not at all strange that the same race should have used both for sepulture, when we consider that a “gallery grave” is an artificial cave, and that natural caves are few in number.

This ancient race is proved by the remains to have been pastoral, rather than dependent on the chase, their principal food being the domestic goat, the short-horn (Bos longifrons), the horse, and hog104. They are also proved to have been neolithic, not merely by the discovery of a polished stone axe in one of the caves, but also by the shape of the “gallery graves,” which Professor Nilsson and Dr. Thurnam agree in referring to that stage of culture.

Table of Contents of Caves and Chambered Tomb.

The contents of the caves and the stone chambers may be gathered from the Table which we give on the next page.

The broken bones of the hare prove that there was no prejudice against its flesh, as was the case among the neolithic dwellers105 in the Swiss Pfahlbauten. We shall see in the next chapter that the animal was also eaten by the dwellers in the neolithic caves both of France and Belgium.

166

List of Objects in Neolithic Caves and Cairn in North Wales.

Animals. Refuse-

heap,

Perthi-

Chwareu. Cave No.1. Cave No. 2. Cave

Rhosdigre

No. 1 Cave

Rhosdigre

No. 2. Cave

Rhosdigre

No. 3. The Cefn

Cave. Cairn of

Tyddyn

Bleiddyn,

near Cefn.

DOMESTIC.

Canis familiaris—Dog X X X X X X X

Sus scrofa—Pig X X X X X X X X

Equus caballus—Horse X X X X X X

Bos longifrons—Celtic Short-horn X X X X X X

Capra hircus—Goat X X X X X X X X

WILD.

Canis lupus—Wolf X

Canis vulpes—Fox X X X X X X

Meles taxus—Badger X X X X X X

Ursus arctos—Bear X

Sus scrofa—Wild Boar X

Cervus elaphus—Stag X X X

Cervus capreolus—Roe X X X

Lepus cuniculus—Rabbit X X X X X

Lepus timidus—Hare X X X X

Polished Celts X

Flint Flakes or Chips X X X X

Pottery X X X X

Human Skeletons X X X X X X X

Platycnemic bones X X X X X X X

Description of the Human Remains by Professor Busk.

For the following account of the human remains, reprinted from the “Journal of the Ethnological Society,” January 1871, I am indebted to the kindness of my friend Professor Busk, to whom examples of all the forms were forwarded:—

Notes on the Human Remains. By Professor Busk, F.R.S.

§ 1. Introduction.

The remains discovered in the sepulchral cave at Perthi-Chwareu, according to a list furnished by Mr. Boyd Dawkins, are as under; but167 I believe this catalogue does not include all that were found in the locality.102

1. Eleven more or less perfect skulls, some, however, represented by mere72 fragments.

2. Twelve mandibles.

3. Seven arm-bones or humeri—four right and three left.

4. Six uln?.

5. Twenty-two thigh-bones, including five pairs, five odd ones of the right side, and seven of the left; and amongst them are three of very young children.

6. Seventeen tibi? or leg-bones, nine of the right and eight of the left side, and apparently none of them in pairs; so that there must probably have been a good many more.

7. Eight astragali.

8. Nine calcanea, or heel-bones.

The number of individuals, therefore, whose relics were deposited in this cavern106 could not have been less than sixteen, and may have been many more. They appear to have been of all ages and of both sexes.

Of the other bones of the skeleton, of which there must have been abundance, I have received no information.

In the Cefn Cave there were discovered:—

1. One mandible.

2. One humerus.

3. Two uln?.

4. A pair of thigh-bones.

5. A pair of leg-bones.

and in the tumulus:—

1. Portions of seven skulls.

2. Two right humeri.

3. A pair of uln?.

4. A right femur.

From St. Asaph the only bone that has come under my observation is a single calvaria.

§ 2. Description of the Bones from the Cavern at Perthi-Chwareu.

(a.) General Condition.—In general condition, as regards colour and texture107, these bones present some, but no very striking, differences;168 on the whole they are much alike, though it might be supposed that some have lain longer in the ground than the others. One or two among them (but these are apparently the younger bones) are fragile; the majority, however, are as firm as common churchyard bones, and some have quite the natural degree of hardness. They are of a lightish-yellow colour, do not adhere to the tongue, and afford scarcely any earthy smell when breathed upon or moistened: only one among them presents any staining from oxide108 of manganese; and this exists in diffuse109 blotches110, and is not at all of the dendritic form. Many are partially covered with a very thin film of crystalline carbonate of lime.

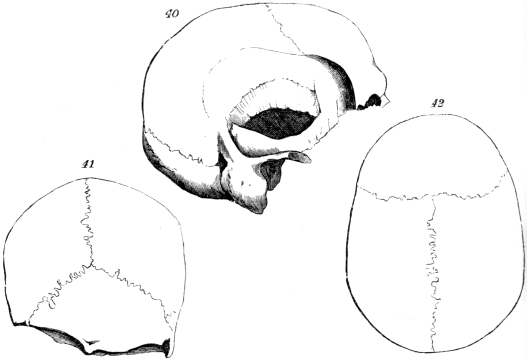

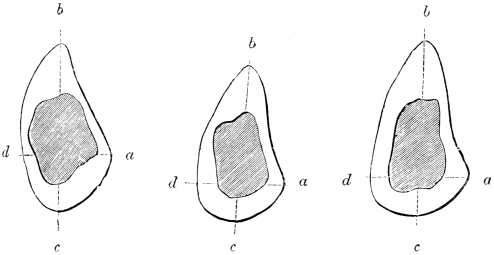

Figs. 40, 41, 42.—Skull from Sepulchral Cave at Perthi-Chwareu.

(b.) The Skulls.—Of these only three of the more perfect have come under my observation. These alone will form the subject of what I have to remark on this portion of the skeleton. But in the subjoined Table I. (p. 171) I have given, together with the dimensions of these three, those of five others which have been furnished to me by Mr. Dawkins.

In the specimen111 No. 1 (Figs 40, 41, 42) the entire facial part is wanting, together with the whole of the base and a great part of one side of the calvaria. The skull is of an oval form, symmetrical, with a rather prominent occiput. The region of the vertex is slightly and evenly arched; and the forehead, though not high, is vertical, and169 slightly compressed on the sides. The sutures are all open and finely serrated. The frontal sinuses are distinct though small. The supra-orbital ridge is thin, but rather prominent towards the external angular process. The mastoid processes are very large, and the digastric fossa remarkably112 deep. The occipital spine113 is very prominent, as are the lateral114 ridges. The temporal ridges, also, and, in short, all the muscular impressions, are very strongly marked.

The skull is evidently that of a powerful, muscular man, in the prime of life, and apparently of robust115, but not coarse build.103

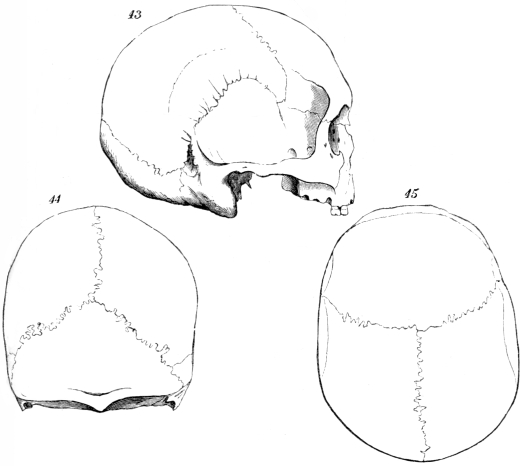

Figs. 43, 44, 45.—Skull from Sepulchral Cave at Perthi-Chwareu.

Skull No. 2 (Figs. 43, 44, 45) is that of an adult male, presenting as nearly as possible the same dimensions, form, and other characters as that above described, except that the bone is somewhat thicker and heavier. The muscular ridges and impressions are even more strongly170 developed than in the former, and especially the temporal ridges immediately above the external angular processes. The left maxilla remains loosely attached, containing the two bicuspid teeth, which are of small size, and worn quite flat, and to such an extent as to render it probable that the man was somewhat advanced in years, although none of the sutures are closed. The face is strictly116 orthognathous, and the skull dolichocephalic and aphanozygous.104

Skull No. 3 is the entire calvaria of a very young individual. The two milk-molars remain on either side; and behind them the first true molar is fully out, but not in the least worn. The incisors and canines117 have fallen out. The former, from the size of the alveoli, were of the permanent set, but not the latter. The age of the individual, therefore, may be estimated as about seven or eight.

The only point worthy of notice in this calvaria is the existence of a well-marked depression across the middle of the occipital bone, which appears exactly as if it had been caused by the constriction118 of a bandage. The depression barely extends beyond the lambdoidal suture into the parietals. It requires, perhaps, some imagination to perceive the slight traces of a corresponding depression in the forepart of the skull; but I think a faint depression may be there perceived on careful inspection119. The effect of the occipital constriction, if it be such, reminds one of some of the deformed120 French skulls described by M. Foville105 and by M. Gosse.106 In all other respects the skull is well formed and symmetrical. It is strictly orthognathous, and of a broad oval shape.

If deformed artificially, it would come under the head of “tête annulaire” of M. Gosse; and Dr. Foville shows that this kind of deformation121 arises from the popular custom of applying a kind of bandage round the head of the new-born infant, which, passing over the anterior122 fontanelle, descends123 obliquely125, and is crossed behind the occiput and brought back and tied in front. This band, or “serre-tête,” he states, is worn during the first year, and for a longer period by female children than by males. Dr. Lunier gives pretty nearly the same account, adding, however, further particulars.107 It may be remarked, also, that the Berbers, who formed great part of the Moorish171 forces that invaded Europe in the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries, used to elongate126 the skull posteriorly and flatten51 the forehead.

Table I.—Dimensions of Perthi-Chwareu Skulls.

No. Length. Breadth. Height. Least frontal breadth. Greatest frontal breadth. Parietal breadth. Occipital breadth. Zygomatic breadth. Frontal radius127. Vertical radius. Parietal radius. Occipital radius. Maxillary radius. Fronto-nasal radius. Circum-

ference. Longi-

tudinal arc. (a) Frontal. (b) Parietal. (c) Occipital. Frontal transverse arc. Vertical transverse arc. Parietal transverse arc. Occipital transverse arc. Latitudinal128 or cephalic index. Altitudinal index.

1. 7·5 5·7 — 4·0 5·0 5·5 4·6 — — — — — — — 21·2 — 5·0 5·5 — 12·0 13·0 14·0 12·0 ·760 —

2. 7·6 5·7 5·4 4·0 4·9 5·5 4·8 — 4·9 5·0 5·2 4·4 — 3·7 21·6 15·9 5·5 5·6 4·8 13·0 13·5 13·8 12·4 ·750 ·710

3. 6·5 5·2 5·5 3·4 4·5 5·1 4·1 3·9 4·2 4·5 4·7 4·1 3·2 3·0 19·0 14·7 4·9 5·3 4·5 11·6 ?12·45 13·4 11·2 ·800 ·846

4. 7·4 5·8 5·8 3·9 5·0 5·8 4·4 4·7 4·4 4·6 4·7 4·3 3·9 3·6 23·5 16·9 5·0 5·0 6·? 11·0 13·0 14·0 12·0 ·797 ·797

5. 6·7 5·0 — 3·5 4·4 5·4 4·1 — 4·0 4·3 4·6 4·0 — — 18·5 — 4·4 5·2 — 11·0 12·5 13·4 — ·746 —

6. 6·8 5·4 — 3·6 4·3 5·3 4·0 — 4·3 4·5 4·8 4·2 — — 19·8 14·6 4·8 5·3 4·5 14·0 12·0 13·0 11·0 ·794 —

7. — 5·5 — — — 5·3 — — — — 4·6 4·0 — — — — — — — — — — — — —

8. 7·0 5·2 — 3·6 4·4 5·2 4·1 — 4·1 4·3 4·5 4·1 — 3·4 19·5 — 4·5 4·9 4·8 11·0 11·5 13·0 12·0 ·743 —

MeanA ?7·07 5·5 5·6 3·8 ?4·64 5·4 4·3 — 4·3 4·5 4·7 4·2 3·5 ?3·42 20·0 15·3 4·9 5·2 5·0 12·0 12·5 13·5 11·8 ?·765A —

Cefn Cave 7·4 5·7 5·2 3·8 4·7 5·5 4·8 — 4·6 4·6 4·7 4·0 — 3·8 21.0 15·1 5·0 5·5 4·6 12·2 12·8 13·8 12·0 ·770 ·702

Cefn Tumulus ?7·38 ?5·65 — 3·6 4·5 ?5·55 — — 4·5 4·6 4·9 4·5 — 3·6 — — 5·2 5·2 — 12·4 12·4 12·8 10·9 ·765 —

Ditto 7·2 5·6 5·7 3·6 ?4·35 5·5 ?4·35 4·6 ?4·45 4·8 4·9 4·3 — 3·7 20·1 — 5·0 5·0 4·9 12·0 13·1 ?13·25 11·5 — —

7·5 5·4 5·9 4·0 4·6 ?5·35 ?4·35 4·9 5·0 5·0 ?5·05 ?4·35 4·2 4·2 20·9 — 4·9 5·6 4·6 12·8 ?13·25 ?13·25 10·5 — —

Genista Cave,

Gibraltar ?7·95 5·5 5·7 3·9 5·0 5·4 ?4·45 5·2 4·7 4·8 4·9 ?4·25 4·1 ?3·75 20·6 14·0 5·2 4·8 4·0 12·5 13·2 13·3 11·4 ·748 ·714

Ditto ?7·35 5·6 6·1 3·8 4·9 5·4 4·5 5·2 ?4·75 4·9 5·1 4·9 4·0 ?3·65 20·8 15·3 4·8 5·6 4·9 12·3 13·2 13·3 11·6 ·761 ·889

A In taking this mean, the cephalic index of the young skull, No. 3, is omitted; if included, the mean would be ·785.

Fig. 46.

(c.) Thigh-bones.—I have had an opportunity of examining only a single perfect specimen of the thigh-bones. This is an entire bone, 18·2 inches long, with a least circumference129 of 3·5. Its perimetral index108 consequently is ·192, which is about the normal standard. The linea aspera, at the middle of the bone more especially, is very prominent, so that the bone may be termed, in some degree, carinated (Fig. 46). The shaft130 is straight; and the chief peculiarities, besides the prominent linea aspera, which it presents, are (1) an unusual compression in the antero-posterior direction in the upper part, for the extent of about three inches below the trochanter minor131. At about two inches below that process, or at a point corresponding with the lower part of the insertion of the pectineus muscle, the shaft measures ·9 × 1·45, whilst in three other ordinary femora with which I have compared it, the bone at the corresponding part measures ·9 × 1·20, ·9 × 1·10, ·9 × 1·15, showing that the Perthi-Chwareu femur is unusually expanded laterally132 in the upper part of the shaft. The consequence is to give the bone at that part a peculiar aspect, which is especially seen in an acute internal angle, and one rather less acute externally, instead of the usually rounded internal and external borders. (2) The distal extremity133 appears to be rather disproportionately large as compared with a recent well-formed bone of the same length, the condyles measuring 2·5 × 3·3 instead of 2·4 × 3·05; and the lower part of the shaft is also somewhat expanded. But the chief peculiarity134, as above remarked, is the compression of the shaft in the upper part. Besides the linea aspera, all the muscular impressions are strongly marked, and especially those for the insertion of the gluteus maximus and the trochanter minor. The neck is long and very oblique124, and the head, upon which only a small portion of the articular surface is left, must have had a diameter of about 1·9.

Mr. Boyd Dawkins has furnished me with the principal dimensions of several other femora, varying in length from 16 to 18 inches, and affording an average length of about 17, corresponding to a mean height of the individuals of about 5 ft. 4 in. to 5 ft. 5 in., the tallest being173 perhaps 5 ft. 6 in., and the shortest about 5 ft. 2 in., no doubt a woman. The mean perimetral index of the eight femora is ·186, which shows, in comparison with the usual thickness of well-formed male thigh-bones of the present day, a certain degree of slenderness. That this is not altogether owing to the circumstance that the bones include those of perhaps more than one female is proved by the fact that in no instance does the perimetral index exceed ·192, and in one thigh-bone, 18″·2 long, it is not more, if the circumference is correctly given, than ·178, the normal perimetral index for the adult male femur in this country being taken as about ·194.

(d.) Tibi?.—Of the leg-bones brought under my notice, five are entire and five more or less defective135. The principal dimensions and proportions of these bones, so far as they could be taken, are given in the subjoined Table.

Table II.—Dimensions, &c., of Perthi-Chwareu Tibi?.

No. Length. Transverse

diameter,

proximal

end. Least

circum-

ference. Antero-

posterior

diameter and

transverse

diameter

of shaft. Perimetral

index. Latitudinal

index.

1. 14·9 2·8 3·2 140 × 80 ·214 ·571

2. 13·7 2·7 2·9 120 - 75 ·211 ·625

3. 13·2 3·0 3·0 135 × 80 ·227 ·592

4. 12·9 2·5 2·5 125 × 70 ·193 ·541

5. 12·9 2·5 ?2·75 100 × 70 ·211 ·700

6. — — — 135 × 90 — ·666

7. — — — 140 × 90 — ·642

8. — — — 130 - 70 — ·538

9. — — — 135 × 85 — ·629

Mean. 13·5 2·7 ?2·86 129 × 79 ·211 ·611

In this Table the length means the extreme length of the bone as measured from the summit of the spinous process to the point of the internal malleolus; and the numbers in the fifth column represent the antero-posterior and the transverse diameter of the shaft at the point where the popliteal line terminates at the inner border of the bone, which is usually about an inch and a half below the nutritive foramen. The latitudinal index represents the relation that the transverse diameter bears to the antero posterior, and it is employed to indicate, with some degree of precision, the actual amount of compression or flattening of the shaft as compared with the normal174 form, which may, so far as my observations show, be taken for the ordinary English tibi? as from ·700 or ·800, or in the mean at ·730, as will be seen in the subjoined Table, which contains the proportions of thirteen leg-bones taken indiscriminately from a drawer in the College of Surgeons.

Table III.—Proportions, &c., of ordinary Tibi?.

No. Length. Transverse

diameter,

proximal

end. Least

circum-

ference. Antero-

posterior

diameter and

transverse

diameter

of shaft. Perimetral

index. Latitudinal

index.

1. 16·7 ?3·15 3·4 130 × 100 ·202 ·769

2. 16·4 3·2 3·5 150 × 115 ·213 ·766

3. 15·8 ?2·95 3·0 120 × 90 ·189 ·750

4. 15·5 ?2·95 2·9 140 × 90 ·122 ·642

5. 15·3 2·9 2·8 130 × 90 ·150 ·692

6. 15·2 3·0 3·2 140 × 90 ·213 ·642

7. 15·0 2·8 2·8 140 × 90 ·187 ·642

8. 15·0 2·6 2·8 120 × 85 ·187 ·709

9. 15·0 2·6 2·8 120 × 90 ·187 ·782

10. 15·5 3·0 2·9 120 × 95 ·193 ·791

11. 13·5 2·8 2·9 120 × 90 ·214 ·750

12. 13·4 ?2·75 2·7 120 × 85 ·201 ·708

13. 12·8 2·5 2·4 100 × 85 ·187 ·850

Mean. 15·1 ?2·88 2·9 126 × 91 ·188 ·730

Comparison of the mean proportions given in the two Tables shows:—

(1) That the Perthi-Chwareu leg-bones are, on the whole, shorter, and absolutely smaller in all dimensions but one, viz. in the antero-posterior diameter of the shaft, which, notwithstanding the smaller size generally of the bones, is rather greater (that is to say, in the proportion of 129 to 126) than in the ordinary run of English tibi?.

(2) That their perimetral index is greater, showing that, in proportion to their length, the Welsh bones are somewhat thicker, or in the proportion of 211 to 188.

(3) But the most marked difference is seen in the latitudinal index, which in the Perthi-Chwareu bones is ·611, and in those of the ordinary type ·730, varying in the former case from ·538 to ·700, and in the latter from ·642 to ·850; but the last is probably an exceptional case. In accordance with this, we find that the mean transverse175 diameter of the shaft at the point above indicated is greatly under the usual mark, viz. as 79 to 91.

It is clear, therefore, that the Perthi-Chwareu tibi? are more compressed or flattened136 than the usual run of modern European tibi?; in other words, they belong to the platycnemic type.

As this is, I believe, the first instance in which the occurrence of tibi? of this peculiar conformation has been observed in this country, the circumstance is of some interest, especially with relation to the occurrence of priscan bones of the same type elsewhere.

This peculiar conformation of the tibia, to which we gave the name of “platycnemic,” was, I believe, first noticed by Dr. Falconer and myself, in 1863, in the human remains procured137 by Captain Brome from the Genista Cave, on Windmill Hill, Gibraltar, of which an account will be found in the Transactions of the International Congress of Prehistoric Arch?ology for the year 1868 (p. 161); and about the same time, or in May 1864, M. Broca109 independently observed the same condition in tibi? procured from the dolmen of Chamant (Oise), and afterwards in bones from the dolmen of Maintenon (Eure-et-Loire). Similar bones have since been noticed in other localities on the Continent, as, for instance, in the diluvium of Montmartre, by M. Eugène Bertrand. But that the peculiarity in question is not common in all the varieties of priscan man belonging to the reindeer period is shown by the fact that it has not been observed in any of the tibi? exhumed138 by M. Dupont in the Belgian caves.

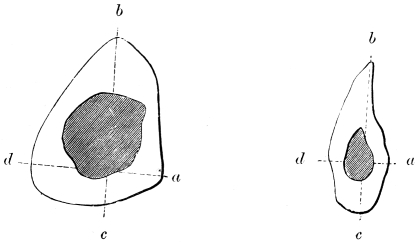

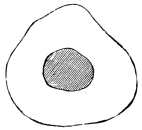

M. Broca’s almost exhaustive remarks upon the anatomical, physiological139, and pathological relations of this form of tibia leave but little to be said under those heads. I would, however, venture to add a few words as to its ethnological significance. But before doing so I would remark that there appear to be two forms of platycnemism, apparently indicative of some difference in the cause or nature of this aberration140 from the more usual shape of the bone. To save many words, I subjoin outlines of several well-marked instances of platycnemic bones, all drawn of the natural size and in the same position, the letter (a) in each corresponding to the interosseous ridge, and (b) to the crista or shin.

The line b c, drawn through the crista and the middle of the posterior surface of the bone, is bisected by another (a d), drawn at right angles to it, at the level of the interosseous ridge.

176 In Fig. 47, which represents what may be regarded as a normal tibia, the length of that portion of the antero-posterior line which is behind the transverse line is to that of the anterior as 274 to 1,000, whilst in Fig. 48, taken from M. Broca’s outline of the Cro-magnon tibia, which would seem to represent the extremest degree of platycnemism as yet observed, the proportion in question is as 623 to 1,000.

Figs. 47, 48.

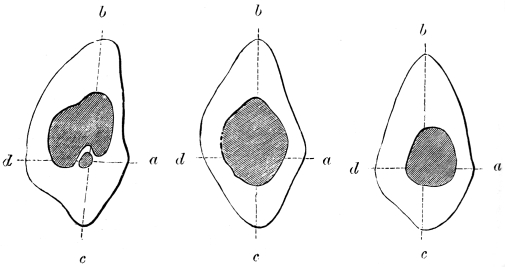

Figs. 49, 50, 51.

Figs. 49, 50, 51, are taken from as many of the Gibraltar tibi?,110 in which the proportion varies from 600 to 523, whilst it will be observed that in Figs. 52, 53, 54, taken from the most platycnemic of the Perthi-Chwareu tibi?, the proportion in one only differs in any considerable177 degree from the extreme normal proportion shown in Fig. 47; and in this it is as 512 to 1,000, whilst in Fig. 53, which is nevertheless undoubtedly platycnemic, the proportion is exactly the same as in the most triangular form of bone.

It would seem, therefore, that platycnemism may arise from an unusual antero-posterior expansion of the bone, either in front or behind the level of the interosseous ridge. What this difference may indicate, or of what importance it may be in the consideration of questions relating to platycnemism, I am not prepared to discuss; but as in all probability it is connected with a difference in the cause of the deformation (if it be deformation), I have thought that the observation should be recorded, and would merely, in addition, remark that, so far as I have noticed, the occasional and not infrequent platycnemism observed in the shin-bones of negroes is what may be termed anterior.

Figs. 52, 53, 54.

With respect to the ethnological value of the platycnemic tibia, I conceive we are as yet very much in the dark. That it is a race-character would seem to me in the highest degree improbable, seeing that it would be difficult to find any other points of resemblance between the Cro-magnon platycnemic men and those whose remains were met with in the Gibraltar caves, although the platycnemism is of the same kind in each; and still less could the former gigantic race be identified with the occupants of the Perthi-Chwareu sepulchre, from whom they differ not only in stature141, but even more remarkably in cranial conformation.

If, then, platycnemism cannot be regarded as of any value as a race-character, it can a fortiori be still less looked upon as indicative178 of simian142 tendencies, a notion that M. Broca seems somewhat inclined to favour. It is quite true that the tibi? of the gorilla143 and of the chimpanzee are, to a certain extent, platycnemic; but it is by no means so much so as the human platycnemic bone. The tibia of a male gorilla in the College of Surgeons has a latitudinal index of ·681, and that of a female of ·650, whilst that of the chimpanzee is ·611, or exactly the mean of the Perthi-Chwareu bones. It is needless to insist upon the other marked distinctions between the simian and the human tibia; but as regards platycnemism it will be obvious, if we are disposed to trace it to any genetic144 descent, that the descendant has, in this respect, at one time far out-simianized the Simi?.

But this comparison with the anthropoid145 apes may, perhaps, afford ground for a suggestion respecting some possible connection between this peculiar form of the tibia and the habits of the people amongst whom it has been observed. One great distinction between the human and the simian foot consists in their respective adaptations to totally distinct functions. In the one case it is simply an organ of support and progression; in the other, for the most part, of prehension. This necessarily involves a considerable difference in the proportions, &c., of the muscles by which the greater mobility146 and adaptability147 of the foot, and more particularly of the digits148, are ensured. Would it not, then, be admissible to inquire how far, at any rate, posterior platycnemism may be connected with the greater freedom of motion and general adaptability of the toes enjoyed by those peoples whose feet have not been subjected to the confinement149 of shoes or other coverings, and who at the same time have been compelled to lead an active existence in a rude and rugged150 or mountainous and wooded country, where the exigencies151 of the chase would demand the utmost agility152 in climbing and otherwise?

Some common cause of this kind would seem to be not improbable; and it would not, perhaps, be difficult to ascertain whether it is a vera causa or not. But, with respect to this, observations are at present wanting.

From the foregoing data we may conclude:—

(1) That the Perthi-Chwareu bones belonged to a race characterized by the proportionally rather large dimensions of the cranium, whose form presents nothing very remarkable, and is pretty nearly conformable to several of those found by Mr. Laing in the ancient shell-mounds in Shetland.179111

(2) That this form is distinctly different from that of the Mewslade skull, in which the vertical region is somewhat flattened, as is the case also with several Anglesey crania, which, however, appear to pass, by gradual transition, into the Keiss and Perthi-Chwareu shape, through such a form as that of the Towyn-y-capel skull figured by Professor Huxley;112 and the whole of them consequently may be regarded as belonging to the so-called “River-bed skulls” of that author, excepting the Borris cranium, which appears to belong to a different type altogether.

(3) That the people whose remains were found in this locality were of low stature (the mean height, deduced from the lengths of the long bones, being little more than 5 feet), the tallest being 5 ft. 6 in., and the shortest adult not more than 4 ft. 10 in., the intermediate ones being 5 ft. 1 in. and 5 ft. 2 in.

(4) That the proportions of the long bones are rather thick, and the muscular impressions in all are very strongly marked.

(5) That the tibi? are, for the most part, of a much more compressed form than those of the modern English, but that this platycnemism does not appear to be exactly of the same kind as that which is exhibited in the Gibraltar bones and in those from Cro-magnon (as figured by M. Broca), the difference consisting in the fact that in the two latter instances the bone is expanded backwards153 behind the transverse plane at the interosseous ridge as much as it is in front of180 that plane, whilst in the Welsh tibi? it is the anterior portion of the shaft only which is expanded; or, in other words, the platycnemism in them is due simply to an absolute compression of the shaft.

§ 3. Human Remains from the Cefn Tumulus.

These remains, as submitted to my inspection, consist of:—

(1) Portions of three frontal bones, two of which are nearly complete, and one constituted of little more than the superciliary region.

(2) Two parietals and a left temporal, probably belonging to the same skull as the more mutilated frontal.

(3) Portions of four thigh-bones, two left and two right, one of the latter wanting the proximal, the other both extremities154.

We have thus the remains of three individuals from this interment.

I. The Frontal Bones.—No. 1. The least transverse diameter, immediately behind the external angular processes, is 3″·6, and its greatest (at the coronal suture) about 4″·3. Longitudinal arc, 4″·1. The profile outline of the forehead is slightly receding96; the frontal sinuses moderately developed; and the supraorbital border thin and acute, whilst the glabellar eminence155 is large and prominent. The bone is a good deal compressed on the sides, so as to have almost the appearance of having formed part of a cymbecephalic skull. The bone itself is thin, and probably without any diplo?.

No. 2 presents exactly the same characters, except that the longitudinal arc is greater, being 5″·3. The postorbital or least transverse diameter is 3″·4, and the coronal or greatest 4″·4. The frontal sinuses are well developed; the supraorbital ridge rather prominent, but thin and sharp; the external angular process prominent and thick. Glabellar eminence large and prominent. The nasals remain in situ, and project almost, if not quite, horizontally forwards, with a rapid curve at first, and then straight out. The general contour of the bone is exactly like that of No. 1, in which also, although the nasals are wanting, the position of the surface by which they were attached shows that they must in all probability have resembled those of No. 2. The crista galli of the ethmoid, which is left in situ, is remarkably thick and high.

No. 3 is a portion of a larger and wider bone, the postorbital diameter being at least 4″·0. The frontal sinuses are very large, but distinctly defined, as the remainder of the supraorbital border is not thickened. Owing perhaps to the greater prominence156 of the sinuses, the glabella does not appear so protuberant157 as in the other instances.181 The nasal bones remain and project forwards in the same curious fashion as in No. 2. The frontal crest158 on the inner surface is remarkably developed, being at least half an inch high, though it is separated by a wide notch159 from the equally strongly developed crista galli of the ethmoid.

No. 4, when the three bones of which it is composed are put together, consists of the greater part of the parietal region of the skull, to which, as before said, the last-described frontal may have belonged. The left parietal is quite perfect; and a considerable portion of the right also remains, together with the entire left temporal; so that a very sufficient estimate of the proportions of the parietal region of the skull can be obtained.

As well as can be estimated, the parietal longitudinal arc, or length of the sagittal suture, is 5″·2. The vertical transverse arc, or that drawn from one auditory foramen to the other, over the point of junction160 of the coronal and sagittal sutures, is 12″·2, the parietal 13″, and the occipital 12″·2. In the temporal bone, the external auditory foramen is large, the mastoid process of moderate size, but the digastric fossa is wide and deep. The channels for the middle meningeal artery161 and its branches are large and deep; and very deep depressions on the sides of the sagittal suture show that the glandul? Pacchioni must have been greatly developed. The bone is very thin, and with scarcely a trace of diplo? where its structure is visible. None of the sutures, however, which are strongly serrated, are in the slightest degree closed, although, as I should imagine, the skull must have been that of a man beyond the middle period of life.

II. The Thigh-bones.—Two of these bones, which, though much alike, differ sufficiently162 to show that they did not belong to the same individual, are decidedly carinate.

No. 1 wants the upper and lower ends. The least circumference of the shaft, which is at a point about 3? inches below the trochanter minor, is 3″·2. That process, as well as all the other muscular impressions, is strongly developed; and that for the insertion of the gluteus maximus is peculiar in presenting the form of a deep elongated163 pit instead of a roughened elevation164 as usual. The antero-posterior and transverse diameters of the shaft, about 1? inches below the trochanter minor, are ·85 × 1·4; and the shaft at this part, like that of the above-described from Perthi-Chwareu, presents a rather acute or narrow external and internal border instead of the usual more rounded form. Lower down, the shaft becomes strongly carinate; and, owing to the flattened form of the anterior surface, its transverse section affords a subtriangular figure (fig. 55). The walls, or cortical substance, are182 rather thicker than usual, and the substance of the bone is dense165 and hard.

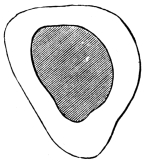

Fig. 55.

Fig. 56.

No. 2 is very similar in character to the foregoing, but is not quite so much compressed in the upper part, measuring ·8 × 1·2. Nevertheless the inner border is very acute, and the outer more so than in the common form of femur. The shaft lower down is not so strongly carinate as it is in the former instance, but is still so in some degree (Fig. 56); and the walls (or cortical substance) are still thicker in proportion.

Fig. 57.

Fig. 58.

No. 3. A third specimen consists of the lower half, or rather more, of the right femur. The least circumference is 3″·2. The bone exhibits no special external characters, and is in no degree carinated. The shaft, at about the middle of its length, is somewhat angular in front; and the pit for the origin of the popliteus muscle is deeper and perhaps larger than in most bones of the same size. The texture of the cortical substance is quite eburneous; and it is extremely thick, so that the medullary canal is reduced to a calibre of little more than 0″·25 in its longest diameter. The shaft, however, is straight, and exhibits no other sign whatever of having been affected166 with rachitis. It is, however, a curious circumstance that many of the Gibraltar thigh-bones, most of which are carinate, present the same thickening of the cortical substance (Fig. 57).

183 No. 4. A fourth specimen is constituted of merely a portion of the shaft, about 12 inches long, and without either extremity. Its least diameter is 3″·3, and its antero-posterior and transverse diameters, at the same point as in the other bones, 1 × 1·25, or pretty nearly in the usual proportions. Nevertheless the bone, throughout its whole remaining extent, is less rounded on the inner side of the shaft than is usual. The trochanter minor is of gigantic size; and the shaft of the bone, about and below the middle, exhibits a subtriangular aspect (Fig. 58), though scarcely to be called carinate. The cortical substance is of the normal thickness.

III. Tibi?.—No. 1 consists of the greater portion of the left tibia, wanting only the lower extremity. The proximal end measures 2·9 × 1·9; and the diameters of the shaft, about the middle, are 1·2 × ·75, giving a latitudinal index of ·620. The shin is remarkably sharp and prominent, and rather curved over to the outer side; and the apparent compression or tendency to platycnemism may in some measure be referred more to the production in front of the anterior part of the bone than to actual narrowing of the posterior side of the triangle, which is nevertheless rather more rounded than in most cases. The axis167 of the shaft is quite straight; and the bone has not the least rickety appearance.

No. 2 is also a portion of the left tibia. Both extremities are wanting, and the bone offers nothing worthy of remark. Its least circumference is 2″·65; and the shaft, at the middle, measures 1″·1 × ·65; so that the latitudinal index is about ·640, showing a slight degree of compression. The entire length of the bone may be estimated as rather more than 13 inches, corresponding to a height of about 5 ft. 4 in. or 5 ft. 5 in., so that the subject may be supposed to have been a female.

These remains represent at least four individuals—one probably somewhat aged168, another of strong and robust make, and one, in all probability, a woman—in fact, a family group. No correct idea can be formed of the cranial conformation of these persons. In general shape it would seem to correspond with that of the Perthi-Chwareu skulls; but two of them at any rate are of smaller size, if we may judge from the least frontal diameter. The forehead also is perhaps a little more reclined. The most striking feature in two of the specimens169, and which appears also to have existed in a third, is the extraordinary projection170 forwards of the nasal bones. In the present case this may probably be regarded as a family peculiarity; but with reference to it, it should be remembered that M. Broca113 has184 described a very similar condition in the skull of the “Old man” of Cro-magnon, in whom, he says, “the ridge of the nose, slightly depressed171 at its base, rises again almost immediately, and advances boldly forward, making a rapid curve, with the concavity directed rather forward and especially upward, so that the lower ends of the ossa nasi are placed 18 mm. (·7 inch) in front of a line dropped vertically172 from the fronto-nasal suture.”

The condition of the bones from the Cefn tumulus differs very considerably173 from that of the remains from Perthi-Chwareu. They all have an appearance of much greater antiquity. With the exception of the very dense femur, they adhere to the tongue; and they are all deeply stained with manganous oxide, by which the substance even of the hardest portions is stained to a depth of more than one-eighth of an inch. That this discoloration, which for the most part does not assume the dendritic appearance, is due to manganese and not to any vegetable stain, is quite certain.

The form of the skull, so far as it can be ascertained174 from such imperfect remains, and the rather platycnemic shape of the tibi?, may perhaps justify175 our supposing that the Cefn bones belong to a cognate176 race to those whose remains were deposited at Perthi-Chwareu, or to one which had lived under similar conditions. But the cranial data are hardly sufficient to allow of any satisfactory inference being drawn from them: and as regards the tibi?, it has already been pointed177 out that platycnemism cannot, in the present state of our knowledge, be regarded as an important ethnological character amongst priscan peoples, though it may undoubtedly be considered a character betokening178 remote antiquity.

§ 4. Skull from the Cefn Cave, near St. Asaph.

The only specimen of human remains from this locality is a nearly entire calvaria, wanting the whole of the face below the superciliary border.

In the middle of the left parietal bone is a small irregular opening, with short radiating lines of fracture proceeding179 from it; but this appears to have been recently caused, and from the inside.

The bone generally is of a brown colour, and, as regards firmness, in a natural condition; and it does not adhere to the tongue. Judging from its aspect alone, it would not appear to be of any very great antiquity; but as it has lain in a dry soil, and sheltered from rain or moisture, this appearance may be deceptive180.

185 Its dimensions are given in Table I. (supra), from which it will be seen that the cephalic or latitudinal index is ·770, and the altitudinal ·702. It belongs, therefore, to the category of subbrachy-cephalic skulls of Thurnam and Professor Huxley.

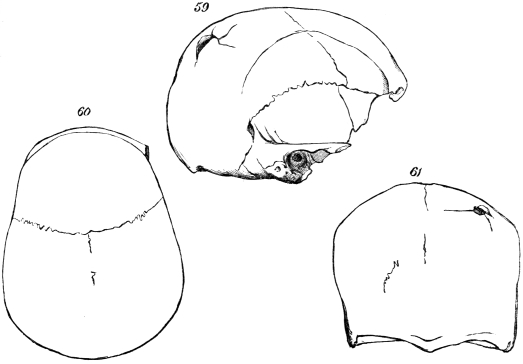

Figs. 59, 60, 61.—Skull from Cave at Cefn, St. Asaph.

In the side view (norma lateralis—Plate 7, Fig. 59), it so closely resembles, except in one respect, that described and figured by Professor Huxley (loc. cit. p. 125, Figs. 60, 61) from the bed of the Nore, at Borris, in Ireland, that we can scarcely refuse to recognize a common character between them, which, since in the present case it cannot be looked upon as denoting a mere family relationship, may reasonably be regarded as indicative of some affinity181 of race. The chief difference observable in this view of the two skulls is the greater development of the frontal sinuses in the Borris calvaria. The occipital view (norma occipitalis, Fig. 8 is also very similar, except that in the Borris skull the greatest width appears to be in the temporal, and in the other the parietal region. In the Borris skull, also, there is a shallow groove182 in the course of the sagittal suture, which does not exist in that from St. Asaph.

The Borris skull is said to be of the extraordinary length of 8 inches; and this may account for the much lower cephalic index of the skull, whose absolute width in reality somewhat exceeds the Cefn186 specimen (5″·9 and 5″·7), whilst the altitudinal as compared with the latitudinal is but very little greater than it would be were the skulls reduced to the same breadth. They may both, therefore, be regarded as “low,” or, as this class of skull might be termed, in the euphonious183 language of craniologists, “tapinocephalic.” One great peculiarity of the Cefn cranium (which exists also, but apparently not to quite so great a degree, in the other) is the absolute horizontality of the plane of the subinial portion of the occipital bone. And it is to this flattening that the comparative lowness may perhaps be chiefly attributed.

The sutures, where visible, appear to be open. The mastoid processes and all other muscular impressions are strongly marked.

A third skull of very similar character, except that it is not so much depressed, has come under my observation. It was discovered in a submarine or, rather, subterranean peat-bed or ancient forest, 30 feet below the sea-level, at Sennen, near the Land’s End, in Cornwall; and a brief notice and outline figure of it will be found in the “Natural History Review” for 1861.114 The Sennen skull has the same elongated form; but it is higher than either the Cefn, St. Asaph, or Borris crania, having an altitudinal index of ·730.

On the whole, these three skulls (i.e. those from Borris, Sennen, and St. Asaph) would appear to have a common character, and to be of a different type from either the Perthi-Chwareu or the Mewslade form.

As a rule it may, I think, be stated that in all brachy-cephalic skulls the breadth exceeds the height, whilst the reverse is the case in the dolicho-cephalic. Individual exceptions are of course not unfrequently met with, more especially among very mixed races, such as the modern English; but I am myself acquainted with only two dolicho-cephalic races, properly so termed, in which the rule does not hold good. These are the Tasmanian (not Australian) and the Bushman.

Any exceptions, therefore, to either rule among ancient and, consequently, less mixed races are worthy of being noted184.

As regards modern brachy-cephalic skulls the law holds almost universally, the only marked exception, except in an individual here and there, being in two Karén skulls, in which, although both decidedly brachy-cephalic, the respective indices stand as ·848 to ·924, and as ·790 to ·842.

Among priscan brachy-cephalic skulls the most remarkable and important exceptions I have met with occur among the neolithic crania in the Copenhagen Museum, more than half of which are brachy-187cephalic, and most of the others nearly so, the mean cephalic index of 21 skulls being ·790, whilst the mean altitudinal is as high as ·810. In fact, out of 12 skulls whose indices vary from ·795 to ·838, no fewer than 10 have the latitudinal index less than the altitudinal.

The exceptions to the rule as applied185 to dolicho-cephalic skulls also appear to be far more common among the ancient than among the modern, excepting the two races I have above referred to.

In a long list of ancient and priscan skulls, I find the following having the tapino-cephalic character:—

L. Ind. Alt. Ind.

1. From the Thames alluvium at Old Ford8 ·792 ·753

2. From the same deposit at East Ham ·774 ·690

3. From the same deposit at Battersea ·763 ·745

4. From the same deposit at London Bridge ·762 ·611

5. From tumulus at Stanshope ·763 ·684

6. A Guanche skull ·775 ·737

7. A Guanche skull ·763 ·684

8. Cefn, St. Asaph’s ·770 ·702

The number is but small, it must be confessed, and perhaps hardly sufficient to do more than prove the rule; but still I think it will be found worth inquiry186 whether a departure from the rule in question was more frequent among the unmixed or little-mixed races of ancient times than it is amongst similarly unmixed races of the present day; and whether consequently its infraction187 in a considerable number of instances may or may not be indicative of a lower type, as which we are accustomed to regard the Tasmanian and Bushman races.

General Conclusions as to Human Remains.

The human remains in the caves of Perthi-Chwareu and Cefn, and in the cairn near the latter place, imply that the men to which they belonged were a short race, the tallest being about 5 feet 6 inches, and the shortest 4 feet 10 inches.115 Their skulls are orthognathic,116 or not188 presenting a lower jaw advancing beyond the vertical line dropped from the forehead; in shape ortho-cephalic, or subbrachy-cephalous, and of fair average capacity. The face was oval and the cheek-bones were not prominent. Some of the individuals were characterised by the peculiar flattening of shin (platycnemism), which probably stood in relation to the free action of the foot that was not impeded188 by the use of a rigid189 sole or sandal. This character, however, is neither peculiar to race, nor to be viewed as a tendency towards the simian type of leg. These conclusions, which Professor Busk has arrived at from the examination of the remains which were submitted to him, have been fully borne out by the numerous skeletons which have been subsequently discovered, both in the sepulchral caves at Rhosdigre and in a second chamber in the cairn of Tyddyn Bleiddyn near Cefn.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

neolithic

|

|

| adj.新石器时代的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

sepulchral

|

|

| adj.坟墓的,阴深的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

chamber

|

|

| n.房间,寝室;会议厅;议院;会所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

scanty

|

|

| adj.缺乏的,仅有的,节省的,狭小的,不够的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

prehistoric

|

|

| adj.(有记载的)历史以前的,史前的,古老的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

Ford

|

|

| n.浅滩,水浅可涉处;v.涉水,涉过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

limestone

|

|

| n.石灰石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

shale

|

|

| n.页岩,泥板岩 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

strata

|

|

| n.地层(复数);社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

ridges

|

|

| n.脊( ridge的名词复数 );山脊;脊状突起;大气层的)高压脊 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

ridge

|

|

| n.山脊;鼻梁;分水岭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

abrupt

|

|

| adj.突然的,意外的;唐突的,鲁莽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

badger

|

|

| v.一再烦扰,一再要求,纠缠 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

roe

|

|

| n.鱼卵;獐鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

gnawed

|

|

| 咬( gnaw的过去式和过去分词 ); (长时间) 折磨某人; (使)苦恼; (长时间)危害某事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

relics

|

|

| [pl.]n.遗物,遗迹,遗产;遗体,尸骸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

atmospheric

|

|

| adj.大气的,空气的;大气层的;大气所引起的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

epoch

|

|

| n.(新)时代;历元 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

reindeer

|

|

| n.驯鹿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

mammoth

|

|

| n.长毛象;adj.长毛象似的,巨大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

rhinoceros

|

|

| n.犀牛 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

antiquity

|

|

| n.古老;高龄;古物,古迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

provincials

|

|

| n.首都以外的人,地区居民( provincial的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

abode

|

|

| n.住处,住所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

underneath

|

|

| adj.在...下面,在...底下;adv.在下面 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

silt

|

|

| n.淤泥,淤沙,粉砂层,泥沙层;vt.使淤塞;vi.被淤塞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

excavated

|

|

| v.挖掘( excavate的过去式和过去分词 );开凿;挖出;发掘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

supervision

|

|

| n.监督,管理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

penetrated

|

|

| adj. 击穿的,鞭辟入里的 动词penetrate的过去式和过去分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

apparently

|

|

| adv.显然地;表面上,似乎 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

figs

|

|

| figures 数字,图形,外形 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

skull

|

|

| n.头骨;颅骨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

perpendicular

|

|

| adj.垂直的,直立的;n.垂直线,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

devoted

|

|

| adj.忠诚的,忠实的,热心的,献身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

excavating

|

|

| v.挖掘( excavate的现在分词 );开凿;挖出;发掘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

tusk

|

|

| n.獠牙,长牙,象牙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

skulls

|

|

| 颅骨( skull的名词复数 ); 脑袋; 脑子; 脑瓜 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

entirely

|

|

| ad.全部地,完整地;完全地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

implement

|

|

| n.(pl.)工具,器具;vt.实行,实施,执行 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

flake

|

|

| v.使成薄片;雪片般落下;n.薄片 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

downwards

|

|

| adj./adv.向下的(地),下行的(地) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

charcoal

|

|

| n.炭,木炭,生物炭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

pebbles

|

|

| [复数]鹅卵石; 沙砾; 卵石,小圆石( pebble的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

pebble

|

|

| n.卵石,小圆石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

boulder

|

|

| n.巨砾;卵石,圆石 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

flatten

|

|

| v.把...弄平,使倒伏;使(漆等)失去光泽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

flattening

|

|

| n. 修平 动词flatten的现在分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

peculiarities

|

|

| n. 特质, 特性, 怪癖, 古怪 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

juxtaposition

|

|

| n.毗邻,并置,并列 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

vertical

|

|

| adj.垂直的,顶点的,纵向的;n.垂直物,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

corpses

|

|

| n.死尸,尸体( corpse的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

posture

|

|

| n.姿势,姿态,心态,态度;v.作出某种姿势 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

insufficient

|

|

| adj.(for,of)不足的,不够的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

cemetery

|

|

| n.坟墓,墓地,坟场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

celebrated

|

|

| adj.有名的,声誉卓著的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

implements

|

|

| n.工具( implement的名词复数 );家具;手段;[法律]履行(契约等)v.实现( implement的第三人称单数 );执行;贯彻;使生效 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

dwelling

|

|

| n.住宅,住所,寓所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

badgers

|

|

| n.獾( badger的名词复数 );獾皮;(大写)獾州人(美国威斯康星州人的别称);毛鼻袋熊 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

mingled

|

|

| 混合,混入( mingle的过去式和过去分词 ); 混进,与…交往[联系] | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

burrowing

|

|

| v.挖掘(洞穴),挖洞( burrow的现在分词 );翻寻 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

crouching

|

|

| v.屈膝,蹲伏( crouch的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

flakes

|

|

| 小薄片( flake的名词复数 ); (尤指)碎片; 雪花; 古怪的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

pottery

|

|

| n.陶器,陶器场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

Oxford

|

|

| n.牛津(英国城市) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

jaw

|

|

| n.颚,颌,说教,流言蜚语;v.喋喋不休,教训 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

mere

|

|

| adj.纯粹的;仅仅,只不过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

axe

|

|

| n.斧子;v.用斧头砍,削减 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

clan

|

|

| n.氏族,部落,宗族,家族,宗派 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

followers

|

|

| 追随者( follower的名词复数 ); 用户; 契据的附面; 从动件 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

fully

|

|

| adv.完全地,全部地,彻底地;充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

unity

|

|

| n.团结,联合,统一;和睦,协调 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

isolation

|

|

| n.隔离,孤立,分解,分离 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

loam

|

|

| n.沃土 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

excavations

|

|

| n.挖掘( excavation的名词复数 );开凿;开凿的洞穴(或山路等);(发掘出来的)古迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

stratum

|

|

| n.地层,社会阶层 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

glutton

|

|

| n.贪食者,好食者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

systematic

|

|

| adj.有系统的,有计划的,有方法的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

rev

|

|

| v.发动机旋转,加快速度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

partially

|

|

| adv.部分地,从某些方面讲 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

slab

|

|

| n.平板,厚的切片;v.切成厚板,以平板盖上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

scattered

|

|

| adj.分散的,稀疏的;散步的;疏疏落落的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

ascertain

|

|

| vt.发现,确定,查明,弄清 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

infancy

|

|

| n.婴儿期;幼年期;初期 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

interred

|

|

| v.埋,葬( inter的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

lieutenant

|

|

| n.陆军中尉,海军上尉;代理官员,副职官员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

worthy

|

|

| adj.(of)值得的,配得上的;有价值的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

insulation

|

|

| n.隔离;绝缘;隔热 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

slabs

|

|

| n.厚板,平板,厚片( slab的名词复数 );厚胶片 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

triangular

|

|

| adj.三角(形)的,三者间的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

receding

|

|

| v.逐渐远离( recede的现在分词 );向后倾斜;自原处后退或避开别人的注视;尤指问题 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

quartz

|

|

| n.石英 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

chambers

|

|

| n.房间( chamber的名词复数 );(议会的)议院;卧室;会议厅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|