Since, however, Pliny’s authority was Rumour5, and since, also, such a phenomenon is a physical impossibility—for no bonfire could produce a temperature at which sand would fuse—it is possible that Rumour in Pliny’s day had a no greater reputation for reliability6 than in the twentieth century. But the story, if not true, is at least well invented and serves to show at how early an age in the world’s history glass was known.{2}

It is more than probable that the place of its origin was Ancient Egypt, and that the Ph?nicians, who were undoubtedly7 acquainted with its use, drew their knowledge from the workers on the banks of old Nile. At any rate articles of glass have been discovered in tombs of the fifth and sixth dynasties—some 3300 years before Christ. This, the earliest known glass, is generally opaque8, and is chiefly used to form small articles of ornament9, such as beads10 for necklaces, etc. The “aggry” beads, found in Anglo-Saxon barrows and made in our own time by the Ashantis and neighbouring tribes, are of similar type. Some admirable specimens11 of ancient Egyptian glass are to be found in the British Museum. Among them is a turquoise-blue opaque glass jar of Thothmes III.—the greatest of all the kings of Egypt—dating from about 1550 B.C.

At a later date glass was extensively made in Alexandria, the sand in the vicinity being of exceptional purity and so, suitable for its manufacture. The city speedily became celebrated12 for the beauty of its output, and articles of Alexandrian glass were largely exported to Greece and to Rome, where also, in the space{3} of a few years, glass-houses were established; and to Constantinople, which was, in time, to become famous for the manufacture of coloured glass and of the Mosaics13 so dear to the Oriental taste.

The Greeks do not appear to have developed the art of glass-making at a very early age, but specimens of glass have been found in Grecian tombs, and, in the Golden Age of Ancient Greece, when art and literature reached their zenith under Pericles, glass was certainly employed for purposes of architectural decoration.

In Rome, however, the art of glass manufacture found a congenial home and was developed to a high pitch of excellence14. So widespread was its use that it is a truism to say that in Rome of two thousand years ago glass was employed for a greater number of purposes—domestic, architectural, and ornamental15—than it is to-day, even though the glazing16 of windows was in its infancy17 and the use of the material for optical purposes was scarcely known. In effect, coloured and ornamental glass held much the same place in the Roman household that china and earthenware18 do among us to-day. Glass was used for{4} pavements and for the external covering of walls. The Roman glass-workers were particularly happy in their combination of colours, both by fusing together threads of various colours, or by fusing masses, so as to imitate onyx, porphyry, serpentine20, and other ornamental stones.

The most interesting of all was the famous cameo glass. A bubble of opaque white glass was blown, and this was coated with blue and a further layer of opaque white superimposed. The outer coat of blue was removed from the portion which was to display the design, leaving the white to be carved into whatever figures the artist’s fancy dictated22. The finest example extant of this kind of ware19 is the famous Portland vase in the British Museum.

The art, thus brought to such perfection in Rome, naturally spread throughout Italy and the Roman colonies in France, Spain, Germany, and Britain. Probably workmen from the Italian cities also established the first furnaces among the lagoons23 of Venice, and so laid the foundation of what were to be the finest glass manufactories in the world. At the end of the thirteenth century a guild24 of glass-workers{5} was formed. These sequestered25 their craft upon the island of Murano, and there cultivated it with an increasing skill that in a brief space made Venetian glass the marvel26 of the civilised world. The peculiar27 merits of the Venetian product were grace of form and lightness of execution. Many of the vessels28 are surpassingly thin. The quality of the metal, however, leaves something to be desired. It is dull, frequently tinged30 with yellow—due to the presence of iron—or purple—the effect of too great a proportion of manganese. The workmen became so skilful31 that, carried away by the joie d’exécuter, they produced not only the artistic32 forms for which Venetian glass is famous, but all sorts of extravagances—ships, animals, birds, fishes, and so on—whose only merit was to testify to the excellence of a technique which could so triumph over the difficulties of form and material.

Meanwhile, other European nations had taken their cue from Venice, and glass-houses sprang up in various parts of the Continent, particularly in France and in Bohemia; the latter, indeed, speedily became the great rival of Venice.

In England, as we shall see, glass was made{6} during the Roman occupation. Under the Saxons, glass-workers were imported from the Continent, but to judge from the number and variety of the specimens found in Anglo-Saxon tombs, it is probable that it was also manufactured to an equal extent at home. During the Middle Ages the art appears to have fallen into abeyance33, save in a few isolated34 instances to be noted35 later, but in the sixteenth century the custom of using glass vessels was introduced from France and the Low Countries, most of the pieces being imported from Venice. To prevent the money thus expended36 from leaving the country, efforts were made about the middle of the century to establish the art by the aid of workmen from Murano, and the history of glass manufactured in England may be said to have fairly begun. It was undoubtedly stimulated37 by the religious persecutions on the Continent, particularly the Spanish Terror in the Netherlands, for the Low Countries were seriously endeavouring to rival Murano in the art, and the craftsmen38 who fled for refuge to England undoubtedly did much to develop their trade in the country of their adoption39, as did the Huguenot refugees at a later period.

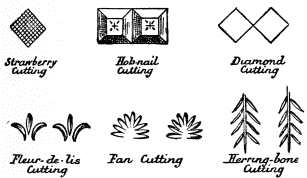

In the seventeenth century the whole process was revolutionised by the introduction of a large proportion of oxide40 of lead, making what is technically41 known as “flint” glass—a glass much more brilliant than any other, a quality due partly to its transparency and partly to its increased refractive power, which renders it specially42 fitted for “cutting”—a process which enhances its beauty by increasing the number of ways in which the light rays falling on the glass are dispersed43. The discovery has given English glass a well-deserved pre-eminence for beauty of metal—a pre-eminence which the glass-cutters of the eighteenth century admirably{8} sustained by the excellence of their work.

All this time the art of glass-making on the Continent had been developing. In particular, the Venetian workers at Murano had perfected the art of colouring and enamelling glass—a result which was later to have its influence upon English artists. An admirable example of what they achieved in this direction is an old spinet45 in the South Kensington Museum, which once belonged to Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia, the daughter of James I. Whatever its merits as a musical instrument, its once gorgeous gilt46 crimson47 leather case hides an interior of the utmost interest to students of glass, for the interior of the lid is panelled into eighteen divisions, each representing some classical subject—Narcissus, Daphne, Andromeda, Argus, etc.—admirably done in coloured glass. The front of the keyboard, the stretcher bar and the keys themselves are also elaborately decorated in similar fashion with coloured glass, silver or enamel44. The keys are covered with ornaments48 in coloured glass, the accidentals being faced with blue and white striped glass and the naturals being fronted with the same.{9}

Although it is no part of the purpose of this book to deal in detail with the technical side of the manufacture of glass, yet some few words as to the nature of the material with which we are dealing49 are not only desirable but essential to the proper understanding of its various qualities and kinds and the different stages of its manufacture.

The scientist will tell us that glass is a double silicate50, being compounded of a silicate of sodium51 (or potassium) and a silicate of lime. For the benefit of non-scientific readers, we may remark that a silicate is a chemical compound formed when silica combines with an alkaline substance like lime, soda52, or potash. Silica is probably the most widely distributed substance in nature. Silicate of alumina is, for example, the basis of all clayey soils, and silica, in the pure form of quartz53, is the chief constituent54 of the sand of the sea and of all those rocks which are known as sandstones. Rock-crystal, amethyst55, agate56, onyx, jasper, flint, etc., are all varieties of silica. Crystalline silica is hard enough to scratch glass—a fact utilised, as we shall see, in the sand-blast which is used for the purpose of engraving57 patterns on glass. Silica{10} is fusible only at a very high temperature, but readily combines with alkaline substances to form soluble58 silicates59, which are known in commerce as soluble glass, or water-glass, because it dissolves readily in hot water. Water-glass is used in making artificial stone, in coating stone surfaces, e.g. walls of buildings, etc., to preserve the stone from decay under the weathering influence of the atmosphere, and in the manufacture of cement.

Ordinary glass has many valuable properties which make it of great importance in the arts and manufactures. Among these may be mentioned the fact that it can be made to take any shape with ease. It resists the action of all ordinary acids, and hence is of the utmost value to the chemist and the chemical manufacturer. Hydrofluoric acid alone attacks it, by combining readily with its silica and so dissolving it. For this reason, hydrofluoric acid is used in etching on glass. Again, glass is cheap, being literally60 made from the dust of the earth; it is transparent61, and so can be used in buildings, transmitting light whilst protecting from the inclemency62 of the weather. Its transparency, too, combined with its high refractive power,{11} make it of inestimable value in the manufacture of optical instruments. It is this high refractive power, too, which gives to cut glass its beautiful lustre63 and sparkle, and one aim of the glass-founder is to increase this refractive power and so enhance the brilliancy of his product. If glass could be made which would refract light to the same extent as the diamond does, it would exhibit the same “fire” as the king of gems64. It is hard and close in texture65, and so is capable of taking a high polish. Its great drawback is its brittleness67, but this can be reduced to a great extent by immersing it, whilst red-hot, in a hot bath of paraffin oil, wax, or resin68. A tumbler of glass so “tempered” may be dropped on the floor without breaking.

It may be added, as a matter of common interest, that this brittleness is largely a result of the fact that glass is an extremely bad conductor of heat. Because of this, a mass of molten glass, when cooling, becomes set on its outside surface long before the interior has become solidified69; hence the solid exterior70 prevents the molecules71 of the interior portion from contracting. As a result, a condition of strain is established, the interior molecules{12} tending to contract, while the exterior tends in the opposite direction; consequently a very slight blow is enough to cause a fracture.

Varieties of Glass.—As we shall frequently find it necessary to refer to the various kinds of glass, it may be as well at the outset to attempt to give a clear idea of their differences and of the meanings of the various terms employed in describing them.

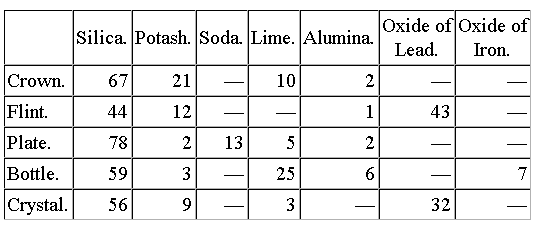

As regards quality, the chief kinds are crown glass, flint glass, plate glass, bottle glass, and crystal glass, and the differences in composition may be conveniently expressed in the form of a table:—

Cheapest of all glass is bottle glass, where the base is mainly lime. The metal used for medicine bottles contains more potash and is purer and clearer. The use of potash and soda makes the glass more easily fusible; alumina has the opposite effect; lime makes a harder glass; lead gives lustre, increases fusibility, and heightens the refractive power. Hence in glass which is to be cut and polished the employment of lead in sufficient quantity is a factor of the highest importance. This is a point to be specially noted in connection with English glass. Lead—chiefly the oxides known as litharge and minium—in small quantities has long been employed, the introduction of the metal serving as a flux72, but lead glass was generally avoided as being too brittle66. Merret, writing in 1662, remarks that could this glass be made as tough as crystalline, “it would far surpass it in the glory and beauty of its colours.” It will be noted that the two kinds of glass in which lead is used in quantity are flint glass and crystal. The larger the amount of lead the greater the beauty and brilliancy of the product, a result due, as previously73 intimated, to the increase in refractive{14} power that is brought about by its addition.

Flint glass derives74 its name from the fact that in England the silica, which is the main constituent of all glass, was procured75 from flints which were calcined and pulverised. Being highly refractive it is extensively employed in the manufacture of optical instruments—telescopes, microscopes, etc. Quartz and fine sand are now used in the place of flints. The glass is soft, and hence easily scratched and dulled. It is essential that only the purest materials be employed, and special furnaces and pots are needed. Flint glass was known in quite early times. It was probably discovered by accident that certain stones were fusible, for fossil glass is found in many places where great fires have been. Volcanic76 glass—obsidian—is a well-known substance, while there exist in Scotland ancient forts, the stones of which have been fused together by the action of heat. The Venetians used quartz in preference to sand, since the latter was liable to contain impurities77, and the Venetian craftsmen who settled in England were accustomed to ensure the purity of their silica by calcining flints. Crown glass{15} is the finest sort of ordinary window glass. Plate glass is the superior kind of thick glass used for mirrors, shop windows, etc. It will be noted that it is the only kind of glass which contains soda.

The process of glass manufacture comprises three stages, mixing, melting, and blowing. The various ingredients are first finely ground and then thoroughly78 mixed by the aid of a mixer, forming what is known as the “batch.” This is placed in melting pots. These are crucibles79 of fire-clay, i.e. clay capable of withstanding the action of heat. The clay must be of the finest quality, and be carefully freed from extraneous80 matters which might affect the quality of the glass. Hence the manufacture of the “pots” is itself an industry of some importance, and as each costs some £10, they form an important item in the expense of manufacture, especially as the pots are short-lived, some eight to ten weeks being the average life of one of them.

The ordinary pot is an inverted81 section of a cone82, the apex83 being closed. For flint glass a covered pot is essential, the form ordinarily adopted being a bell-jar closed at{16} the bottom and with an arched opening at the top. Each pot holds from ten to fifteen cwt. of the “batch.” When full, the pots are placed in specially constructed furnaces, holding from five to fifteen pots, and capable of producing a temperature of from 10,000° to 12,000° F. The details of the firing are intricate and interesting but have no direct bearing on our purpose; their object is to produce complete fusion84, to allow for the removal of all impurities, and to ensure the homogeneity of the product.

The final stage with which we are concerned is that of blowing, since all table glass, worthy85 of being called table glass, is blown. In other words, every decanter, vase, tumbler, and wine glass of the better sort begins its existence as a bubble of molten glass at the end of an iron tube—the glass-blower’s tube—and owes its form to the delicate touches of simple tools held in a skilful hand and guided by a trained eye. It is this fact which gives glass its individuality. There is no hard-and-fast rigour of line, no mechanical uniformity of shape, such as is associated with machine-made goods; even the simplest wine{17} glass is an individual thing, which the taste of the craftsman86 has endowed with artistic distinction whilst retaining its simplicity87 of form.

It is a matter for regret that the glass-blower’s art is seriously threatened in these latter days of hurry and competition. The demand for cheap glass has led to the introduction of blowing machines, in which the bubble of molten glass is taken up by one of many blowing tubes, and placed inside a mould, air being driven by machinery88 through the other end of the tube and inflating89 the bubble until it touches the sides of its mould. The budding craftsman thus loses the practice of blowing these simpler forms, and as he is now forbidden to work at the furnaces until he is over fourteen, he often fails to acquire that lightness and dexterity90 of hand which are the mark of the first-rate craftsman, and which can be most readily gained in early life. There is, of course, no reason why common vessels should not be produced in this way, and tumblers, decanters, and lamp glasses are so manufactured in large numbers.

Needless to say, moulded or pressed glass{18} has little value, either intrinsic or artistic, in the collector’s eye, unless it has acquired distinction on account of its age; for moulded or pressed glass has been known from early times, and it is of the greater interest, since only English glass, i.e. flint glass, or glass of similar characteristics, can profitably be so dealt with. It will be readily understood that only glass of a low melting point, which does not quickly solidify91, and which at the moment of solidification92 expands and fills out the interstices of the mould, can be successfully treated in this way. One bar to the extensive use of this form of glass was the cost of the essential lead and potash. These are often now replaced by baryta and lime, with the result that a very suitable glass is produced, which contains no appreciable93 quantity of either lead or potash.

The art of glass-cutting in Europe dates back to the middle of the sixteenth century, when it was extensively practised on the Continent, particularly in Bohemia. The earliest examples were probably imitated from the rock-crystal cups of ancient Greece and Rome. There is no doubt that in both these{19} countries the art was practised for the ornamentation of the famous crystallinum, whilst some vessels were undoubtedly cut out of the solid block.

The discovery of flint glass revolutionised the art of glass ornamentation. The strong refractive powers of the new glass made it specially suitable for cutting, which brought out a wonderful fire and sparkle that even the finest art of Bohemia and Venice had not been able to attain94. At first, of course, the English craftsmen were far inferior in artistic merit—both as regards design and execution—to those of Bohemia; but the superior brilliancy of the metal atoned95 to a great extent for the deficiencies of the workmen, and Early English cut wine glasses and punch glasses are by no means to be despised. “L’article Anglais solide et confortable, mais sans élégance,” spread the fame and fashion of English glass throughout the Continent and, incidentally, over the world.

The earliest examples of English cut glass are perhaps the thistle-shaped glasses, originally fashioned in Bohemia but adopted by Scotland as representing the national emblem96. Apart{20} from these, the ogee-shape was most commonly selected as being more amenable97 to artistic treatment than the bell.

The stem is usually knopped and cut into facets98, and is invariably hexagonal in shape. The cutting is continued beyond the top of the stem on to the lower part of the bowl, so as to give a kind of finish. Sometimes, indeed, the cutting is made to include the bowl in a scheme of decoration, and the rim21 is engraved99 with conventional designs, wreaths of flowers, etc. Towards the end of the eighteenth century the facets became long flutes101.

The process technically known as glass-cutting is essentially102 one of grinding and polishing. The grinding is done by a wheel, made of cast-iron, and made to rotate rapidly by a continuous band passing over a revolving103 shaft104. Above the wheel is a receptacle containing sand and water, which can be fed on to the wheel as desired. Smoothing is done by a sandstone wheel, similarly mounted, and polishing by a wooden one fed with putty powder. The craftsman holds his piece in the hand, pressing it against the rotating wheel.

Engraving is really very fine grinding, done{21} usually with a copper105 wheel or, rather, disk, whilst etching is done by coating the glass with wax, or some similar protective substance, scratching the pattern through the wax and then subjecting the piece to the action of hydrofluoric acid.

It need hardly be said that only the best kinds of glass are cut by a method which makes such demands on the time and skill of the workman; the cheaper kinds of glass are all moulded or “pressed.” Pressed glass is also essentially English, no other kind, save flint glass, being suitable for treatment in this way. It is, in the first place, essential to obtain a metal which has a low melting point, and one which does not shrink in solidifying106, as that would draw it away from the sides of the mould, and so effectively spoil the design. The low melting point of the metal enables the product to be “fire polished.” In this process it is reheated to a point sufficient to melt a thin surface layer, and so remove any roughness due to the process of moulding, and leave a smooth bright surface. The art of pressing glass has been brought to a high degree of perfection, elaborate decorations being produced{22} with ease. The cost of the process, too, has in recent years been lessened107 by the use of baryta and lime, in the place of lead and potash, and in this way the output has been greatly cheapened, while baryta glass, if inferior in sparkle to lead glass, is yet far more brilliant than ordinary glass.

The problem how to distinguish real old glass from modern imitations is one that besets108 the collector at every stage of his progress. A few specimens supply their own testimony109 in the shape of a date, but it is by no means impossible to engrave100 a date on a piece of specious-looking real antiquity, and so give it a fictitious110 value, by making it appear “the thing which it is not.”

As to the character of the glasses themselves, shape alone is no criterion of age. Apart from the possibility of deliberate imitation, it does not follow that because a piece is ponderous111, clumsy in appearance and, to a modern eye, unduly112 capacious, that it is necessarily an early piece. Right from the beginning of glass manufacture in England, two qualities, at least, were undoubtedly manufactured; the better to ornament the tables of the great, and the poorer for service in kitchen and tavern113.{23} Whereas articles of the former were as dainty and artistic as the skill of the craftsman would allow, the latter were roughly made and deliberately114 ponderous to bear the rougher usage to which they were subjected. As the same practice continues up to the present day, it follows that there is in existence a considerable quantity of common glass with all the attributes, as far as shape and clumsiness of form are concerned, of that of an earlier period.

Possibly the appearance of the metal and the style of workmanship are as reliable guides as any others. The metal of the earliest glasses was by no means perfect. Instead of the beautiful clarity and perfect transparency we are accustomed to associate with glass, there is often a streakiness or cloudiness visible in the material, together with numerous bubbles and flaws. If the striations are horizontal, the glass is of an earlier type than if they are perpendicular115. The sides of the bowl are often irregular, and the stems are often clumsy, uneven116, badly balanced, and altogether disproportionate in point of size to an eye accustomed to the slenderer style of modern glassware. An important point is the junction117 between the bowl{24} and the stem. For some extraordinary reason, the welding of the two seems to have given the ancient glass-blowers considerable trouble, and the join is often too clearly perceptible. Hence the collector who comes across an apparently118 ancient piece bearing evident signs of clumsy joining should give it more than casual attention. Sometimes, to obviate119 the difficulty, the base of the bowl was made into a kind of knop, and at other times the junction was hidden by an irregular band—the prototype of the collar which so often appeared in glasses of a somewhat later period.

The bubble which appears in many stems was probably the outcome of accident and possibly of an attempt to imitate the hollow stems of Venetian glass. It is worthy of note that whilst the bubble is almost invariably present in the baser forms of early eighteenth-century glass, it is frequently absent from the finer varieties. Another point of difference is that the better specimens rarely have the folded foot, which is invariably present in the coarser makes, the turning under of the rim, whilst plastic, to make a kind of welt, being an obvious precaution against the rougher usage to which they were{25} inevitably120 subjected. Sometimes the feet were domed121, but these were difficult to make and the numbers were restricted. In some specimens ridges122 or ribs123 are formed on the upper and lower sides of the foot.

The earliest glasses were devoid124 of any attempt at decorative125 engraving, and these plain glasses may also be roughly classified by noting whether the glass rests on the flat of the foot or on the rim only. The former are of the earlier type.

Among the tests which the collector might apply are the following:—

Note whether the glass rings clear and sweet in tone. In twisted stems, note whether the stem twists to the left or the right. The genuine glasses have almost invariably stems twisted to the left. In opaque-twisted stems, note particularly the colour of the spiral. In the forgeries126 the opacity127 is less definite, the twist often having a kind of translucent128 look.

Genuine old glass often has a cloudy tinge29 with frequently a tone of steely blue. Forgeries may show a greenish tint129.

In old glass the centre of the base, where the piece was, after being finished, knocked off{26} the pontil, is generally left rough; in the imitations it is generally ground smooth.

The foot of a genuine old glass is never quite flat, there is always a slope—sometimes a very pronounced one—from the centre to the edge. The modern imitation, usually made abroad, often has a perfectly130 flat foot.

The edge of the bowl in a genuine old glass is always rounded, never left hard and sharp.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

antiquity

|

|

| n.古老;高龄;古物,古迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

mariners

|

|

| 海员,水手(mariner的复数形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

cargo

|

|

| n.(一只船或一架飞机运载的)货物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

improvised

|

|

| a.即席而作的,即兴的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

rumour

|

|

| n.谣言,谣传,传闻 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

reliability

|

|

| n.可靠性,确实性 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

opaque

|

|

| adj.不透光的;不反光的,不传导的;晦涩的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

ornament

|

|

| v.装饰,美化;n.装饰,装饰物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

beads

|

|

| n.(空心)小珠子( bead的名词复数 );水珠;珠子项链 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

specimens

|

|

| n.样品( specimen的名词复数 );范例;(化验的)抽样;某种类型的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

celebrated

|

|

| adj.有名的,声誉卓著的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

mosaics

|

|

| n.马赛克( mosaic的名词复数 );镶嵌;镶嵌工艺;镶嵌图案 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

excellence

|

|

| n.优秀,杰出,(pl.)优点,美德 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

ornamental

|

|

| adj.装饰的;作装饰用的;n.装饰品;观赏植物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

glazing

|

|

| n.玻璃装配业;玻璃窗;上釉;上光v.装玻璃( glaze的现在分词 );上釉于,上光;(目光)变得呆滞无神 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

infancy

|

|

| n.婴儿期;幼年期;初期 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

earthenware

|

|

| n.土器,陶器 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

ware

|

|

| n.(常用复数)商品,货物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

serpentine

|

|

| adj.蜿蜒的,弯曲的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

rim

|

|

| n.(圆物的)边,轮缘;边界 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

dictated

|

|

| v.大声讲或读( dictate的过去式和过去分词 );口授;支配;摆布 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

lagoons

|

|

| n.污水池( lagoon的名词复数 );潟湖;(大湖或江河附近的)小而浅的淡水湖;温泉形成的池塘 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

guild

|

|

| n.行会,同业公会,协会 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

sequestered

|

|

| adj.扣押的;隐退的;幽静的;偏僻的v.使隔绝,使隔离( sequester的过去式和过去分词 );扣押 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

marvel

|

|

| vi.(at)惊叹vt.感到惊异;n.令人惊异的事 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

vessels

|

|

| n.血管( vessel的名词复数 );船;容器;(具有特殊品质或接受特殊品质的)人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

tinge

|

|

| vt.(较淡)着色于,染色;使带有…气息;n.淡淡色彩,些微的气息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

tinged

|

|

| v.(使)发丁丁声( ting的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

skilful

|

|

| (=skillful)adj.灵巧的,熟练的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

artistic

|

|

| adj.艺术(家)的,美术(家)的;善于艺术创作的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

abeyance

|

|

| n.搁置,缓办,中止,产权未定 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

isolated

|

|

| adj.与世隔绝的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

noted

|

|

| adj.著名的,知名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

expended

|

|

| v.花费( expend的过去式和过去分词 );使用(钱等)做某事;用光;耗尽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

stimulated

|

|

| a.刺激的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

craftsmen

|

|

| n. 技工 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

adoption

|

|

| n.采用,采纳,通过;收养 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

oxide

|

|

| n.氧化物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

technically

|

|

| adv.专门地,技术上地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

specially

|

|

| adv.特定地;特殊地;明确地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

dispersed

|

|

| adj. 被驱散的, 被分散的, 散布的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

enamel

|

|

| n.珐琅,搪瓷,瓷釉;(牙齿的)珐琅质 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

spinet

|

|

| n.小型立式钢琴 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

gilt

|

|

| adj.镀金的;n.金边证券 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

crimson

|

|

| n./adj.深(绯)红色(的);vi.脸变绯红色 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

ornaments

|

|

| n.装饰( ornament的名词复数 );点缀;装饰品;首饰v.装饰,点缀,美化( ornament的第三人称单数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

dealing

|

|

| n.经商方法,待人态度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

silicate

|

|

| n.硅酸盐 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

sodium

|

|

| n.(化)钠 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

soda

|

|

| n.苏打水;汽水 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

quartz

|

|

| n.石英 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

constituent

|

|

| n.选民;成分,组分;adj.组成的,构成的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

amethyst

|

|

| n.紫水晶 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

agate

|

|

| n.玛瑙 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

engraving

|

|

| n.版画;雕刻(作品);雕刻艺术;镌版术v.在(硬物)上雕刻(字,画等)( engrave的现在分词 );将某事物深深印在(记忆或头脑中) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

soluble

|

|

| adj.可溶的;可以解决的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

silicates

|

|

| n.硅酸盐( silicate的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

literally

|

|

| adv.照字面意义,逐字地;确实 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

transparent

|

|

| adj.明显的,无疑的;透明的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

inclemency

|

|

| n.险恶,严酷 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

lustre

|

|

| n.光亮,光泽;荣誉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

gems

|

|

| growth; economy; management; and customer satisfaction 增长 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

texture

|

|

| n.(织物)质地;(材料)构造;结构;肌理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

brittle

|

|

| adj.易碎的;脆弱的;冷淡的;(声音)尖利的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

brittleness

|

|

| n.脆性,脆度,脆弱性 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

resin

|

|

| n.树脂,松香,树脂制品;vt.涂树脂 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

solidified

|

|

| (使)成为固体,(使)变硬,(使)变得坚固( solidify的过去式和过去分词 ); 使团结一致; 充实,巩固; 具体化 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

exterior

|

|

| adj.外部的,外在的;表面的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

molecules

|

|

| 分子( molecule的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

flux

|

|

| n.流动;不断的改变 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

previously

|

|

| adv.以前,先前(地) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

derives

|

|

| v.得到( derive的第三人称单数 );(从…中)得到获得;源于;(从…中)提取 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

procured

|

|

| v.(努力)取得, (设法)获得( procure的过去式和过去分词 );拉皮条 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

volcanic

|

|

| adj.火山的;象火山的;由火山引起的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

impurities

|

|

| 不纯( impurity的名词复数 ); 不洁; 淫秽; 杂质 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

thoroughly

|

|

| adv.完全地,彻底地,十足地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

crucibles

|

|

| n.坩埚,严酷的考验( crucible的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

extraneous

|

|

| adj.体外的;外来的;外部的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

inverted

|

|

| adj.反向的,倒转的v.使倒置,使反转( invert的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

cone

|

|

| n.圆锥体,圆锥形东西,球果 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

apex

|

|

| n.顶点,最高点 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

fusion

|

|

| n.溶化;熔解;熔化状态,熔和;熔接 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

worthy

|

|

| adj.(of)值得的,配得上的;有价值的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

craftsman

|

|

| n.技工,精于一门工艺的匠人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

simplicity

|

|

| n.简单,简易;朴素;直率,单纯 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

machinery

|

|

| n.(总称)机械,机器;机构 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

inflating

|

|

| v.使充气(于轮胎、气球等)( inflate的现在分词 );(使)膨胀;(使)通货膨胀;物价上涨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

dexterity

|

|

| n.(手的)灵巧,灵活 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

solidify

|

|

| v.(使)凝固,(使)固化,(使)团结 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

solidification

|

|

| 凝固 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

appreciable

|

|

| adj.明显的,可见的,可估量的,可觉察的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

attain

|

|

| vt.达到,获得,完成 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

atoned

|

|

| v.补偿,赎(罪)( atone的过去式和过去分词 );补偿,弥补,赎回 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

emblem

|

|

| n.象征,标志;徽章 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

amenable

|

|

| adj.经得起检验的;顺从的;对负有义务的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

facets

|

|

| n.(宝石或首饰的)小平面( facet的名词复数 );(事物的)面;方面 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

engraved

|

|

| v.在(硬物)上雕刻(字,画等)( engrave的过去式和过去分词 );将某事物深深印在(记忆或头脑中) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

engrave

|

|

| vt.(在...上)雕刻,使铭记,使牢记 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

flutes

|

|

| 长笛( flute的名词复数 ); 细长香槟杯(形似长笛) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

essentially

|

|

| adv.本质上,实质上,基本上 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

revolving

|

|

| adj.旋转的,轮转式的;循环的v.(使)旋转( revolve的现在分词 );细想 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

shaft

|

|

| n.(工具的)柄,杆状物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

copper

|

|

| n.铜;铜币;铜器;adj.铜(制)的;(紫)铜色的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

solidifying

|

|

| (使)成为固体,(使)变硬,(使)变得坚固( solidify的现在分词 ); 使团结一致; 充实,巩固; 具体化 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

lessened

|

|

| 减少的,减弱的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

besets

|

|

| v.困扰( beset的第三人称单数 );不断围攻;镶;嵌 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

109

testimony

|

|

| n.证词;见证,证明 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

fictitious

|

|

| adj.虚构的,假设的;空头的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

ponderous

|

|

| adj.沉重的,笨重的,(文章)冗长的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

unduly

|

|

| adv.过度地,不适当地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

tavern

|

|

| n.小旅馆,客栈;小酒店 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

deliberately

|

|

| adv.审慎地;蓄意地;故意地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

perpendicular

|

|

| adj.垂直的,直立的;n.垂直线,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

uneven

|

|

| adj.不平坦的,不规则的,不均匀的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

junction

|

|

| n.连接,接合;交叉点,接合处,枢纽站 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

apparently

|

|

| adv.显然地;表面上,似乎 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

obviate

|

|

| v.除去,排除,避免,预防 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

120

inevitably

|

|

| adv.不可避免地;必然发生地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

domed

|

|

| adj. 圆屋顶的, 半球形的, 拱曲的 动词dome的过去式和过去分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

ridges

|

|

| n.脊( ridge的名词复数 );山脊;脊状突起;大气层的)高压脊 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

ribs

|

|

| n.肋骨( rib的名词复数 );(船或屋顶等的)肋拱;肋骨状的东西;(织物的)凸条花纹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

devoid

|

|

| adj.全无的,缺乏的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

125

decorative

|

|

| adj.装饰的,可作装饰的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

126

forgeries

|

|

| 伪造( forgery的名词复数 ); 伪造的文件、签名等 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

127

opacity

|

|

| n.不透明;难懂 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

128

translucent

|

|

| adj.半透明的;透明的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

129

tint

|

|

| n.淡色,浅色;染发剂;vt.着以淡淡的颜色 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

130

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |