There can be little doubt that the Romans did introduce the making of glass into this country, for glass was an indispensable adjunct to Roman life. Moreover, it was the custom for the conqueror5 to train the conquered in his own arts, and the Roman handicrafts followed the Roman Eagle. In any case, the art of glass-making had, according to Pliny, extended to Gaul, and there seems no reason why it should not also have crossed the Channel. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that it did.{28}

There is, however, evidence that glass-making was carried on in Anglo-Saxon times—many specimens of Anglo-Saxon bead-work, etc., having been found in barrows, tumuli, and burying-places in general. They are composed of an opaque6, vitreous paste—which in places approaches translucency7. Unfortunately, the materials employed were impure8, and the material has consequently disintegrated9 with time, making it a matter of exceeding difficulty to determine its original texture10 and appearance. The decoration, both as regards colouring and design, is primitive11. The colour is crude, and the patterns consist mainly of simple geometrical figures, circles, chevrons14, stripes, spirals, and so forth15.

Possibly after the Roman withdrawal16 in 410, the art fell into abeyance17, as did much of the civilisation18 imposed by the Romans, reviving again when the various Anglo-Saxon units began to develop a civilisation of their own, and to pass through various confederacies into a single kingdom.

Bede writes that in 675 “Benedict Biscop” sent for glass-workers from France to glaze19 the windows of the church at Wearmouth, and that{29} they taught the English their handicraft, making not only windows but vessels21.

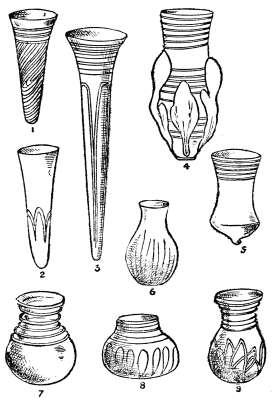

The art must, however, have survived in certain places, for numbers of vessels which can be referred, on the authority of illuminated22 MSS., etc., to Saxon times, are in existence. Such specimens include (a) vases, ornamented24 with ribs25 and applied26 lobes27. These are probably of German origin, and were introduced into Britain by the Saxon invaders28. (b) Trumpet-shaped cups, ribbed, or stringed, or fluted29. These have no base on which to stand, and are probably of English manufacture, dating from the latter half of the sixth century, (c) The third type is the “palm” cup, shaped so as to be conveniently held in the palm of the hand, having no bottom on which to stand; and (d) bowls of various shapes. The palm cups and bowls belong to the eighth and ninth centuries, and later. It should be remembered that the dates given can only be roughly approximate, and that the various periods fuse one into the other, so that there is no definite line of demarcation. Moreover, there is no definite proof that glass vessels were made in England during Saxon times, save only such

statements as that of the Venerable Bede previously30 referred to. Only, while similar vessels are found both in France and Germany, it is claimed that a greater number and a greater variety are found in England, the inference being that they were made in this country.

So remarkable31 is the paucity32 of evidence and so absolute the dearth33 of authenticated34 examples in these Dark Ages of glass manufacture, that it has often been asserted that no glass vessels were made in England before the fifteenth century. Glass vessels were, of course, known and used, but these were probably, in the main at any rate, imported from Venice and the East. On the other hand, it is known that before the thirteenth century window glass—blown glass too, and not cast glass—was made, and very successfully. Indeed, old English coloured glass was particularly fine, and this being so, it is not easy to understand why the same art should not be applied to vessels.

Coarse glass vessels were certainly made at a very early date. The records of Chiddingfold refer to Laurence Vitrearius in 1230, William le Verir in 1301, and John Glasewryth in 1380. The record, in its transition from Latin to{32} Norman-French, and then to Anglo-Saxon, has its philological36 interest as well, but it may be mentioned that John the Glasewryth made both “brode glas and vessel20.”

There is, too, in existence an ancient cup of glass, disinterred from a tomb in Peterborough Abbey Church, which, from the records of the Abbey, must have been buried there, in all probability, in the first half of the thirteenth century. In the accounts of Henry, the second son of Edward I., who died in 1274, there is mentioned the purchase of a glass cup for the sum of twopence halfpenny, a fact which seems to imply that to be sold so cheaply the vessel must have been of domestic manufacture. It should not, however, be forgotten that this sum represented the daily wage of a skilled artisan in the thirteenth century. In the Taxation38 Roll of Colchester in 1295, three of the principal burgesses are referred to as “verrers,” and it seems hardly likely that so many important citizens were merely glaziers and not glass-makers. However, it is more than probable that the use of glass was confined to the noble and wealthy, while the common folk used vessels made of wood, horn, or leather.{33} The “Leather Bottel” has passed into a proverb, and the Black Jack39 was so universal in its use that the French, naturally curious as to English habits, referred to us as a nation of savages40 who habitually41 drank out of their boots. It follows that the Black Jack of the thirteenth or fourteenth century had few of the graces of its silver-mounted and aristocratic descendant of the seventeenth century. It might be further suggested that English habits and customs in those early times were not such as to make fragile drinking vessels either useful or acceptable. Those that did exist were probably rather valued curiosities than articles of everyday utility.

There was, undoubtedly43, produced during this period considerable quantities of window glass, much of it highly decorated, and exhibiting characteristics peculiar44 to the period to which it belongs, so that experts find little difficulty in distinguishing between the vigour45 of the thirteenth and the brilliancy of the fourteenth century. It would appear, too, that the home product won an increasing appreciation46 from the architects who employed it in their buildings; for whereas in 1547 the contractor{34} binds47 himself not to use it for the windows of the Beauchamp Chapel48 at Warwick, in 1485 it is mentioned in such a way as to imply that it was either better or dearer, or both, than “Dutch, Venice, or Normandy glass.”

In the sixteenth century, however, the fashion of using vessels of glass became almost universal in the west of Europe. Most of these came from Venice, and, spurred by the desire of establishing so lucrative49 an industry at home, the rulers of various countries—notably50 France, Holland, and England—sought to induce Venetian craftsmen51 to settle in them.

The glass-workers of Murano—the great glass-making centre in Venice—were, however, a close corporation, the workmen being stringently52 bound, under penalty of death, not to carry their trade secrets to any other country or to teach them to foreigners. In spite of this, eight Muranese glass-workers were induced to settle in England in 1549, and built their furnace in the monastery54 of the Crutched55 Friars—one of the minor56 orders. They derived57 their name Crutched (i.e. Crossed) from the ornamental58 cross which adorned59 their habits. Of{35} the eight, seven returned to Venice in 1551, having previously petitioned the Council of Ten to remit60 the penalties against them. It is a reasonable assumption—but still only an assumption—that during their stay they did much to further the art of glass-making, although they merely produced glass and sedulously61 refrained from teaching their “mystery.”

The “Breviary of Philosophy,” published in 1557, remarks:

“As to glassemakers they be scant62 in this land

Yet one there is as I doe understand,

And in Sussex is now his habitacion,

At Chiddingfold he works by his occupacion.”

Evidently, therefore, the old Sussex industry had survived. The product of the Chiddingfold furnaces was probably, however, a coarse green glass, and by no means to be compared with the Venetian article.

In 1564 Cornelius de Lannoy, an alchemist from the Netherlands, came to England, at the invitation of the Government, to teach the art of glass-making as practised in the Low Countries. He took up his abode63 and set up his furnace in Somerset House. He failed,{36} however, with the materials then available, to produce any very effective results; in particular, the clay used for the pots failed to withstand the great heat required to produce transparent64 glass. Moreover, de Lannoy proved to be more alchemist than glass-maker, and left various persons in England the poorer for their quest after the philosopher’s stone which they had undertaken under his guidance.

In 1567 Pierre Briet and Jean Carré sought a licence to make glass after the French fashion, and to teach to English craftsmen the art of its manufacture as practised in Lorraine and Normandy. Elizabeth, always with an eye to the main chance, made no difficulty and, joining forces with a rival licencee, Becker, set up in opposition65 to the English glass-makers in Sussex and later at Stourbridge and Newcastle. The fact that the native workers openly confessed their inability to compete with the French craftsmen did not prevent their stirring up a strong opposition against them, which found vent42 in popular tumult66 and, in at least one instance, in a conspiracy67 to murder the workers, pillage68 their stores and destroy their furnaces. There seems little doubt, however, that their{37} presence must have influenced the quality of English glass and given an impetus69 to its manufacture. So did the advent70 of political and religious refugees from the Low Countries and from France, and also, though, of course, to a far greater degree, the influx71 of French artisans in the seventeenth century after the revocation72 of the famous Edict of Nantes. In spite of their efforts, however, it does not appear that the importation of fine Venetian glass was in any way checked; it continued, indeed, on an extensive scale for a long time after.

The most famous name in the history of Elizabethan glass manufacture is that of Jacob Verzelini, who came to London in 1575 and stayed for the remainder of his life—about thirty years. He obtained a patent giving him the monopoly of manufacturing glass after the Venetian style for twenty-one years. He set up his establishment in the hall of the Crutched Friars, where the eight Venetians had built their furnace in 1549, and there made “glass of divers73 sorts to drink in.” There is little doubt as to his success, although, with one possible exception, no tangible74 evidence of it remains75. But{38} if one may judge by the very considerable outcry that arose at this period against permitting foreigners to practise the art of glass-making to the detriment76 of native practitioners77, he succeeded sufficiently78 well to arouse a strong feeling of jealousy79. This was intensified80 by the traders who had hitherto sold imported Venetian glass, and the seamen81 who carried it in their vessels and who now saw their livelihood82 menaced.

The general public, too, showed itself greatly concerned over the great consumption of wood in the glass-houses. Indeed, during this period the wasting of the woods was a general complaint wherever furnaces were set up. So strong was this feeling, indeed, that in 1584 an act was passed against the making of glass by strangers and outlandish men and for the preservation83 of woods spoiled by glass-houses; and in 1589, the year after the Armada, it was proposed to reduce the number of glass-houses from fifteen to four, transferring the rest to Ireland, where the loss of trees did not matter so much, the timber not being urgently needed, as in England, for the purpose of shipbuilding. One curious fact is that for a long time—from{39} the twelfth century at least in unbroken record—English window glass of a high order had been produced, as witness the windows of King’s College Chapel at Cambridge, which date from 1515-31; and it seems impossible to conceive that, with Venetian and Eastern glass to copy, the craftsmen who produced the windows should not have also turned their skill to the making of drinking vessels, particularly as the fashion for vessels of glass had strongly set in.

“It is a world to see in these our daies wherein gold and silver most aboundeth how that our gentilitie as lothing these mettals (because of the plentie) do now generalie choose rather the Venice glasses both for our wine and beere than anie of those mettals or stone wherein beforetime we have beene accustomed to drink....

“The poorest also will have glasse if they may but sith the Veneccian is somewhat too deere for them they content themselves with such as are made at home of ferne and burned stone, but in fine all go one way that is to shards84 at the last.”

On the other hand, when Sir Richard Mansel{40} applied in 1624 for a patent to manufacture glass and to train Englishmen in the art, it was opposed, on the ground that fifty years before a similar patent had been granted to Jacob Verzelini and that it had been altogether neglected, and very few Englishmen had been brought up in the art. Mansel, in his reply, stated that he himself had brought many strangers from beyond seas to instruct his fellow-countrymen in making all sorts of glass, crystalline, Murano, spectacle glasses, and mirror plates.

I have stated these facts in the early history of English glass at some length not only for their intrinsic interest, but also to illustrate85 the curious fact that just as there is from Saxon times to 1550 a gap in the history of its manufacture, which no authenticated examples assist to fill, so from the accession of Queen Elizabeth to that of King Charles I. there exist to-day very few indisputable examples of the English glass-blower’s art of this period; and yet it is hardly possible to believe that they were not produced in considerable quantity. For, in spite of specimens bearing the Tudor rose—an ornament23, by the way, largely employed{41} at a later date—and of others with detailed86 and more or less accredited87 histories, “Elizabethan glass,” so glibly88 spoken of by some collectors, is chiefly conspicuous89 by its absence. Happy, therefore, the collector who acquires even a dubious90 example.

One famous specimen1 which may safely be assumed to be authentic35 is that from the British Museum Collection shown in Fig13. 1. This drinking cup or goblet91 stands about 5? in. in height and bears the initials G. S.—probably those of the person for whom it was made—the date 1586, and the motto, “IN: GOD: IS: AL: MY: TRVST.” Experts generally concur92 in attributing it to Jacob Verzelini.

Four years after the Armada, Elizabeth granted to one Thomas Bowes a monopoly to make drinking glasses “to be as good cheape or better cheape than those imported from Venice.” As to the success of his venture history is silent. In the reign53 of her successor—that British Solomon, James I.—glass-making seems, however, to have made considerable progress; for in 1610 a licence was granted for “the invention of coal-heated glass-houses,” and in the following year Sir Edward Zouche expended{42} no less a sum than £5000 in erecting93 glass-houses in Lambeth and perfecting the production of glass with sea-coal. This change is a momentous94 one in the history of glass-making, inasmuch as it became necessary to cover the pots, and this brought about various improvements. They are mainly associated with the name of Percival, and it is to be presumed that they included the introduction of oxide95 of lead into the frit in quantity, with the result of producing a more brilliant crystal than had yet been produced. From this time English glass began to acquire fame, and the industry became a definitely British art.

One outcome of this change in the method of manufacture was that the industry became localised, the glass-houses springing up in those districts where it was easy to obtain fuel as on the coal-fields, where the sand was of exceptional quality as at Reigate, or where there was an abundance of clay suitable for making the pots as at Stourbridge.

One of the most interesting discoveries in connection with the history of the glass industry in England was made some sixty or seventy{43}

FIG. 1.—AN EARLY ELIZABETHAN GLASS, DATED 1586.

FIG. 2.—AN OLD ENGLISH GLASS TANKARD AND COVER.

years ago at the little Hampshire village of Buckholt Wood. Excavations96 here brought to light fragments of glass, some clear, others with a greenish or bluish tinge97, evidently portions of broken vessels of various kinds—drinking glasses, jugs98, bottles, and so forth. These were in such quantity that it was evident chance had brought to light one of the old glass-houses, which were founded in well-wooded districts, and kept going as long as sufficient wood remained to burn.

We have seen how, in the beginning, English glass-workers were a nomad99 race. As the woods in one place were exhausted100 they moved to fresh fields and forests new—much to the annoyance101 of the populace, who depended upon those woods for their household firing, and of the Government, who sought to preserve them for the maintenance of the fleet.

In 1615 a proclamation was made forbidding the use of wood for glass smelting102, the furnaces being in future compelled to burn sea-coal or charcoal103 or other fuel. The same ordinance104 prohibited the importation of foreign glass or the immigration of foreign glass-workers.{44}

In the same year Sir Richard Mansel, a man of considerable standing105 in the realm, who had been experimenting in glass-making with the aid of Venetian workmen, was granted a licence for making glass with coal, and set up furnaces in London and at Purbeck, Milford Haven106 and Newcastle. It is a matter for regret that no product of his furnaces is known to exist to-day, a fact the more surprising in that his licence was renewed at various times, and so covers a considerable stretch of the most interesting period of the art. At any rate we find him petitioning in 1641 that he might be protected against persons importing glass from abroad, whereas he was paying a rent of £1000 per annum for his monopoly. His name is mentioned as late as 1653, so that for nearly forty years he controlled, more or less, the business of glass production in England.

It is a matter for some congratulation, however, that Mansel employed, in some kind of managerial capacity in his Broad Street works, a certain James Howell, who enjoys the reputation of being one of the liveliest and most pleasing writers of the period. In{45} the famous Howell’s letters, “Epistol? Ho-Elian?,” which were published between 1645 and 1655, we have a delightful107 commentary on the events of his time, and incidentally a number of curious and useful sidelights on the conduct of glass manufacture both in England and on the Continent.

It is said that Sir Kenelm Digby, of Royalist fame, invented in 1632 the art of making glass bottles to contain the wine which hitherto had been drawn108 straight from the wood. But Fame which credits him with this discovery would seem to have forgotten that in Elizabeth’s time ale was sold in glass bottles, and a quaint109 old volume yclept “The English Housewife” refers in 1575 to round bottles with narrow necks for “bottle ale,” the corks110 being tied down with stout111 string.

The Commonwealth112, save for what may be gleaned113 from Howell’s pages, adds but little to our knowledge of glass. The Puritans were, perhaps, more addicted114 to smashing it, in the form of stained-glass windows, than manufacturing it for domestic utilities. But with the Restoration there came a great{46} change. The then Duke of Buckingham, who appears, like others of his name, to have had a keen eye to the main chance, started a glass furnace at Greenwich. In 1663 he petitioned the King that he might be granted a licence to make mirrors, he having been at great expense in finding out the art and mystery thereof—“a manufactory not known nor heretofore used in England”—a curious contradiction to Mansel’s claim in 1620, and one which seems to imply that the Duke was by no means particular as to what he said provided he might gain his ends.

There were numbers of competitors at the time all claiming to be the inventors of crystal glass. The authorities, however, awarded the palm to one Thomas Tilson, who in 1663 was granted a patent, in which he is described as the inventor of crystal glass. It appears clear that Tilson had produced a material of greater merit than any of his predecessors115 or contemporaries. It is probable that this material was lead glass—flint glass as it was and is still called. One point in support of this theory is that it was too{47} brittle116 to be used in making vessels, and Tilson consequently confined himself to the manufacture of mirrors, windows for coaches, etc.

Specimens of the work of this period may be found in many places—country houses, mansions117, halls, etc.—throughout the country. At Hampton Court Palace there are, for example, several magnificent mirrors that testify to the skill of the craftsmen—Venetian and English—of this period. Some of the window glass is of the same date and may be readily distinguished118 by its mauve tinge—a possible result of the action of light on the peroxide of manganese, which was one of the constituents119. At a slightly later date other glass-houses were founded in Lambeth, Stourbridge, Newcastle-on-Tyne, and other places, notably in Surrey and Sussex.

All this while, however, there was a great trade in imported Venetian glass, which the Council was, time and again, petitioned to prohibit. Fortunately both for the future of the art of glass-making in England and for the cheapness and quality of the ware120, which was now in great demand, the efforts of the protectionists were unavailing.{48}

Much of our knowledge of the glass of the period is due to the discovery of the trading books and order sheets of one John Greene, who seems to have dealt in imported glass, ordering from the Venetian furnaces vessels to his own specification121 and design. Fortunately some specimens of these are still in existence, but it need hardly be said that examples of the seventeenth century, both home manufactured and imported, are of the extremest rarity. He would be a fortunate collector who should discover, say, “a speckled emerald coverd beere glasse” or a “milk-whit cruet” either with or without “feet and ears of good hansom fashion.”

In point of shape the Venetian and English glasses of this period differ very little, but there is a considerable difference in the character of the metal. The glass from Venice is colder to the eye, whiter and softer than the English, which is more brilliant and of a peculiar steely lustre122, while it is far weightier—a fact probably due to the use of a considerable proportion of lead. The English glasses, too, are heavier in appearance, with stems, thick and lumpy, of the baluster type. Often, too, the bulbous stem is blown with a bubble,{49}

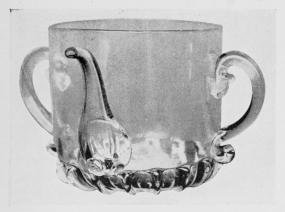

FIG. 3.—AN EARLY GLASS FEEDING CUP.

FIG. 4.—A SIXTEENTH CENTURY PANEL GLASS, WITH PORTRAIT OF CHARLES II.

often of considerable size—a primitive attempt at ornamentation. Not unseldom a coin is inserted in the bulb of the stem or the knop of the cover. One famous example of Caroline glass is the magnificent posset cup in the possession of Miss Whitmore Jones, which is shown in Fig. 2. This unmistakably dates from the time of Charles II. and is a genuine example of English art. It was probably, as to design, copied from a Venetian model, but the texture of the glass and the weight of the piece are strong evidences of its English origin. With the accession of William, the craft was further stimulated123 by the importation of many models, and possibly craftsmen from the Low Countries. Speaking generally however, the vessels of the reigns124 of William and of Anne are but improved specimens of those of Charles. Some, however, have spiral lines cut round the stems, and are, to this extent, the prototypes of the twisted stems of the eighteenth century.

The illustration of a feeding cup (Fig. 3) provides an excellent example of the work of this period. Its admirable shape and style and its exquisite125 workmanship will readily{50} appeal not only to connoisseurs126 but also to all who are capable of appreciating artistic127 merit.

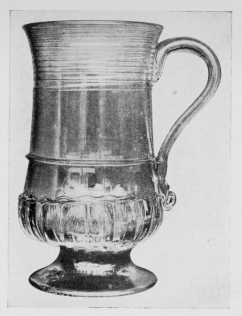

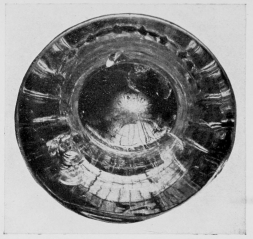

In Fig. 5 we have portrayed128 the prototype of the modern tankard. Judging by the shape and style it was probably an ale glass. But that it was intended rather as a specimen to be preserved is evidenced from the fact that a coin of the period has been blown into the base. Fig. 6 is a photograph showing the coin. Such a piece has almost the value of a dated specimen, for though it was, of course, possible to insert a coin of any previous date, the reason for doing so is by no means obvious. It is hardly likely, for example, that anyone living in William’s reign would have so enthusiastic a regard for Charles II. as to cause a coin of that monarch129 to be embedded130 in a piece that he had made as an heirloom. This specimen is in the British Museum, whose mark appears to the right of the photograph.

The quaint glass panel seen in Fig. 4 is an interesting relic131 of the attention paid to glass-working at this period. The portrait is that of Old Rowley (Charles II.) himself, and the piece was in all probability made at Greenwich, possibly in commemoration of his visit

FIG. 5.

FIG. 6.—THE CENTRE SHOWING THE COIN BLOWN IN THE STEM OF THE TANKARD SHOWN ON THE LEFT-HAND SIDE.

there. It was taken from a house in Purfleet and is now in the National Collection.

The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 gave a vast impetus to glass-working as to other crafts. This measure, and the terrible persecutions which followed it, cost France a number, variously estimated at from 250,000 to 600,000, of her best citizens. Great numbers of these immigrants settled in England, and founded in their new home the industries which had become famous in the country of their birth. Among them came glass-workers from Paris, Lorraine, and other parts of France, who were deservedly famous for their skill in their craft. Coming as they did at a time when the discovery of the brilliant so-called flint glass gave to English glassware a distinction possessed132 by no other, it is small wonder that the next half-century saw such developments in the art of glass manufacture in England that English glass became superior to all other kinds, even to the famous glass of Bohemia, which seemed dull and lustreless133 beside it.

For these reasons the close of the seventeenth century is an epoch134 in the history of English glass, and the period which followed{52} it saw the art of glass manufacture in England attain135 its zenith.

It is therefore with eighteenth-century glass that we are chiefly concerned, and as the great bulk of eighteenth-century glass consisted of drinking glasses, a great portion of our space will be devoted136 to these.

At the outset some attempt at classification is desirable. We may refer the reader to the very exhaustive list of varieties which that great authority, Mr. Albert Hartshorne, has made in his standard work on this subject. For our purpose it will be sufficient, however, to make a broad and simple division of drinking glasses into wine glasses, ale and beer glasses, and cordial or spirit glasses. It is the custom, too, to draw a distinction between the rude vessels made for common household or tavern137 use and the finer and more highly finished examples designed for the use of better-class people. Here, however, the distinction is rather one of quality than of kind.

The three great groups to which we have referred fall into various classes according to the diversity of shape in bowl and stem and, to a less degree, of foot.{53}

The bowls are variously funnel-shaped, with straight sides, or waisted, that is, with the sides curved inward to form a waist, bell-shaped, and ogee or double-ogee shaped—the last named showing in section the ogee curve, so widely employed by the architect for his mouldings.

The stems are of two great classes—drawn stems or stuck stems. The former are parts of the same lump of molten glass of which the bowl is formed; the latter consist of a separate piece fused into the bowl.

As regards shape, stems may be plain rods, rods with knops, rib-twisted, faceted138, air-twisted, air-drawn, or opaque-twisted. We shall deal with each variety in its appropriate place.

With regard to the foot, the generality were folded, that is to say, the edge of the rim12 was turned under to form a fold or welt, so that the glass stands on the rim, and not on the flat of the foot. Apart from this, the only variations are those bearing on the flatness of the foot and its diameter. In old glasses the feet were never quite flat. There is always a perceptible slope from the centre to the rim, and very often the central portion rose up into a dome37. The foot was also wider in{54} comparison with the width of the bowl than in the modern type.

The decoration is of two kinds, engraved139 and cut. The character of the engraving140 is little to the credit of the native designer or craftsman. Indeed, both as regards artistic design or skilful141 execution, English glass ornamentation is distinctly inferior to that of the Continental142 pieces. The usual design is the rose, at first heraldic and conventional, and then more and more natural, with at first a butterfly, which gradually dwindled143 to a moth144, and then finally disappeared. Other designs are based upon the nature of the liquids drunk, or refer to politics, domestic or business affairs, or to some famous personage. The largest group of designs is associated with Jacobitism—“Charlie-over-the-water-ism,” as some one has wittily145 called it. In rare cases these bore a portrait; more commonly the emblem146 selected was the use of two buds—the latter explained as referring to the two sons of James II., or to the two sons of the Old Pretender, Charles Edward of “Charlie-is-my-darling” fame, and Henry, who died at Rome in 1807, as Cardinal147 York.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

specimen

|

|

| n.样本,标本 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

specimens

|

|

| n.样品( specimen的名词复数 );范例;(化验的)抽样;某种类型的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

beads

|

|

| n.(空心)小珠子( bead的名词复数 );水珠;珠子项链 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

craftsman

|

|

| n.技工,精于一门工艺的匠人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

conqueror

|

|

| n.征服者,胜利者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

opaque

|

|

| adj.不透光的;不反光的,不传导的;晦涩的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

translucency

|

|

| 半透明,半透明物; 半透澈度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

impure

|

|

| adj.不纯净的,不洁的;不道德的,下流的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

disintegrated

|

|

| v.(使)破裂[分裂,粉碎],(使)崩溃( disintegrate的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

texture

|

|

| n.(织物)质地;(材料)构造;结构;肌理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

primitive

|

|

| adj.原始的;简单的;n.原(始)人,原始事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

rim

|

|

| n.(圆物的)边,轮缘;边界 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

chevrons

|

|

| n.(警察或士兵所佩带以示衔级的)∧形或∨形标志( chevron的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

forth

|

|

| adv.向前;向外,往外 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

withdrawal

|

|

| n.取回,提款;撤退,撤军;收回,撤销 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

abeyance

|

|

| n.搁置,缓办,中止,产权未定 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

civilisation

|

|

| n.文明,文化,开化,教化 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

glaze

|

|

| v.因疲倦、疲劳等指眼睛变得呆滞,毫无表情 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

vessel

|

|

| n.船舶;容器,器皿;管,导管,血管 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

vessels

|

|

| n.血管( vessel的名词复数 );船;容器;(具有特殊品质或接受特殊品质的)人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

illuminated

|

|

| adj.被照明的;受启迪的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

ornament

|

|

| v.装饰,美化;n.装饰,装饰物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

ornamented

|

|

| adj.花式字体的v.装饰,点缀,美化( ornament的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

ribs

|

|

| n.肋骨( rib的名词复数 );(船或屋顶等的)肋拱;肋骨状的东西;(织物的)凸条花纹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

applied

|

|

| adj.应用的;v.应用,适用 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

lobes

|

|

| n.耳垂( lobe的名词复数 );(器官的)叶;肺叶;脑叶 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

invaders

|

|

| 入侵者,侵略者,侵入物( invader的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

fluted

|

|

| a.有凹槽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

previously

|

|

| adv.以前,先前(地) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

paucity

|

|

| n.小量,缺乏 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

dearth

|

|

| n.缺乏,粮食不足,饥谨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

authenticated

|

|

| v.证明是真实的、可靠的或有效的( authenticate的过去式和过去分词 );鉴定,使生效 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

authentic

|

|

| a.真的,真正的;可靠的,可信的,有根据的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

philological

|

|

| adj.语言学的,文献学的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

dome

|

|

| n.圆屋顶,拱顶 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

taxation

|

|

| n.征税,税收,税金 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

jack

|

|

| n.插座,千斤顶,男人;v.抬起,提醒,扛举;n.(Jake)杰克 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

savages

|

|

| 未开化的人,野蛮人( savage的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

habitually

|

|

| ad.习惯地,通常地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

vent

|

|

| n.通风口,排放口;开衩;vt.表达,发泄 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

undoubtedly

|

|

| adv.确实地,无疑地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

vigour

|

|

| (=vigor)n.智力,体力,精力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

appreciation

|

|

| n.评价;欣赏;感谢;领会,理解;价格上涨 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

binds

|

|

| v.约束( bind的第三人称单数 );装订;捆绑;(用长布条)缠绕 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

chapel

|

|

| n.小教堂,殡仪馆 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

lucrative

|

|

| adj.赚钱的,可获利的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

notably

|

|

| adv.值得注意地,显著地,尤其地,特别地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

craftsmen

|

|

| n. 技工 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

stringently

|

|

| adv.严格地,严厉地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

reign

|

|

| n.统治时期,统治,支配,盛行;v.占优势 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

monastery

|

|

| n.修道院,僧院,寺院 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

crutched

|

|

| 用拐杖支持的,有丁字形柄的,有支柱的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

|

56

minor

|

|

| adj.较小(少)的,较次要的;n.辅修学科;vi.辅修 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

derived

|

|

| vi.起源;由来;衍生;导出v.得到( derive的过去式和过去分词 );(从…中)得到获得;源于;(从…中)提取 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

ornamental

|

|

| adj.装饰的;作装饰用的;n.装饰品;观赏植物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

adorned

|

|

| [计]被修饰的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

remit

|

|

| v.汇款,汇寄;豁免(债务),免除(处罚等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

sedulously

|

|

| ad.孜孜不倦地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

scant

|

|

| adj.不充分的,不足的;v.减缩,限制,忽略 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

abode

|

|

| n.住处,住所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

transparent

|

|

| adj.明显的,无疑的;透明的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

opposition

|

|

| n.反对,敌对 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

tumult

|

|

| n.喧哗;激动,混乱;吵闹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

conspiracy

|

|

| n.阴谋,密谋,共谋 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

pillage

|

|

| v.抢劫;掠夺;n.抢劫,掠夺;掠夺物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

impetus

|

|

| n.推动,促进,刺激;推动力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

advent

|

|

| n.(重要事件等的)到来,来临 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

influx

|

|

| n.流入,注入 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

revocation

|

|

| n.废止,撤回 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

divers

|

|

| adj.不同的;种种的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

tangible

|

|

| adj.有形的,可触摸的,确凿的,实际的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

remains

|

|

| n.剩余物,残留物;遗体,遗迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

detriment

|

|

| n.损害;损害物,造成损害的根源 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

practitioners

|

|

| n.习艺者,实习者( practitioner的名词复数 );从业者(尤指医师) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

jealousy

|

|

| n.妒忌,嫉妒,猜忌 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

intensified

|

|

| v.(使)增强, (使)加剧( intensify的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

seamen

|

|

| n.海员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

livelihood

|

|

| n.生计,谋生之道 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

preservation

|

|

| n.保护,维护,保存,保留,保持 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

shards

|

|

| n.(玻璃、金属或其他硬物的)尖利的碎片( shard的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

illustrate

|

|

| v.举例说明,阐明;图解,加插图 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

detailed

|

|

| adj.详细的,详尽的,极注意细节的,完全的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

accredited

|

|

| adj.可接受的;可信任的;公认的;质量合格的v.相信( accredit的过去式和过去分词 );委托;委任;把…归结于 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

glibly

|

|

| adv.流利地,流畅地;满口 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

conspicuous

|

|

| adj.明眼的,惹人注目的;炫耀的,摆阔气的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

dubious

|

|

| adj.怀疑的,无把握的;有问题的,靠不住的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

goblet

|

|

| n.高脚酒杯 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

concur

|

|

| v.同意,意见一致,互助,同时发生 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

erecting

|

|

| v.使直立,竖起( erect的现在分词 );建立 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

momentous

|

|

| adj.重要的,重大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

oxide

|

|

| n.氧化物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

excavations

|

|

| n.挖掘( excavation的名词复数 );开凿;开凿的洞穴(或山路等);(发掘出来的)古迹 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

tinge

|

|

| vt.(较淡)着色于,染色;使带有…气息;n.淡淡色彩,些微的气息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

jugs

|

|

| (有柄及小口的)水壶( jug的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

nomad

|

|

| n.游牧部落的人,流浪者,游牧民 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

exhausted

|

|

| adj.极其疲惫的,精疲力尽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

annoyance

|

|

| n.恼怒,生气,烦恼 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

smelting

|

|

| n.熔炼v.熔炼,提炼(矿石)( smelt的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

charcoal

|

|

| n.炭,木炭,生物炭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

ordinance

|

|

| n.法令;条令;条例 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

standing

|

|

| n.持续,地位;adj.永久的,不动的,直立的,不流动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

haven

|

|

| n.安全的地方,避难所,庇护所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

delightful

|

|

| adj.令人高兴的,使人快乐的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

drawn

|

|

| v.拖,拉,拔出;adj.憔悴的,紧张的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

quaint

|

|

| adj.古雅的,离奇有趣的,奇怪的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

corks

|

|

| n.脐梅衣;软木( cork的名词复数 );软木塞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

commonwealth

|

|

| n.共和国,联邦,共同体 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

gleaned

|

|

| v.一点点地收集(资料、事实)( glean的过去式和过去分词 );(收割后)拾穗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

addicted

|

|

| adj.沉溺于....的,对...上瘾的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

predecessors

|

|

| n.前任( predecessor的名词复数 );前辈;(被取代的)原有事物;前身 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

brittle

|

|

| adj.易碎的;脆弱的;冷淡的;(声音)尖利的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

mansions

|

|

| n.宅第,公馆,大厦( mansion的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

118

distinguished

|

|

| adj.卓越的,杰出的,著名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

119

constituents

|

|

| n.选民( constituent的名词复数 );成分;构成部分;要素 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

120

ware

|

|

| n.(常用复数)商品,货物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

121

specification

|

|

| n.详述;[常pl.]规格,说明书,规范 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

122

lustre

|

|

| n.光亮,光泽;荣誉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

123

stimulated

|

|

| a.刺激的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

124

reigns

|

|

| n.君主的统治( reign的名词复数 );君主统治时期;任期;当政期 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

125

exquisite

|

|

| adj.精美的;敏锐的;剧烈的,感觉强烈的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

126

connoisseurs

|

|

| n.鉴赏家,鉴定家,行家( connoisseur的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

127

artistic

|

|

| adj.艺术(家)的,美术(家)的;善于艺术创作的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

128

portrayed

|

|

| v.画像( portray的过去式和过去分词 );描述;描绘;描画 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

129

monarch

|

|

| n.帝王,君主,最高统治者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

130

embedded

|

|

| a.扎牢的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

131

relic

|

|

| n.神圣的遗物,遗迹,纪念物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

132

possessed

|

|

| adj.疯狂的;拥有的,占有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

133

lustreless

|

|

| adj.无光泽的,无光彩的,平淡乏味的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

134

epoch

|

|

| n.(新)时代;历元 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

135

attain

|

|

| vt.达到,获得,完成 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

136

devoted

|

|

| adj.忠诚的,忠实的,热心的,献身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

137

tavern

|

|

| n.小旅馆,客栈;小酒店 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

138

faceted

|

|

| adj. 有小面的,分成块面的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

139

engraved

|

|

| v.在(硬物)上雕刻(字,画等)( engrave的过去式和过去分词 );将某事物深深印在(记忆或头脑中) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

140

engraving

|

|

| n.版画;雕刻(作品);雕刻艺术;镌版术v.在(硬物)上雕刻(字,画等)( engrave的现在分词 );将某事物深深印在(记忆或头脑中) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

141

skilful

|

|

| (=skillful)adj.灵巧的,熟练的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

142

continental

|

|

| adj.大陆的,大陆性的,欧洲大陆的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

143

dwindled

|

|

| v.逐渐变少或变小( dwindle的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

144

moth

|

|

| n.蛾,蛀虫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

145

wittily

|

|

| 机智地,机敏地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

146

emblem

|

|

| n.象征,标志;徽章 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

147

cardinal

|

|

| n.(天主教的)红衣主教;adj.首要的,基本的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |