Climbing roses, when planted, should be cut down almost to the ground, and also carefully thinned out. Only a few of the strongest branches should be preserved, and the new wood of these cut down to two eyes each.

The preceding remarks are applicable to roses at the time of planting; they should also be pruned6 every year,—the hardy7 varieties in the autumn or winter, and the more tender in the spring. For all roses that are not liable to have part of their wood killed by the cold, the autumn is decidedly the best time for pruning; the root, having then but little top to support, is left at liberty to store up nutriment for a strong growth the following season. The principal objects in pruning are the removal[Pg 94] of the old wood, because it is generally only the young wood that produces large and fine flowers; the shortening and thinning out of the young wood, that the root, having much less wood to support, may devote all its nutriment to the size and beauty of the flower; and the formation of a symmetrical shape. If an abundant bloom is desired, without regard to the size of the flower, only the weak shoots should be cut out, and the strong wood should be shortened very little; each bud will then produce a flower. By this mode, the flowers will be small, and the growth of new wood very short, but there will be an abundant and very showy bloom. If, however, the flowers are desired as large and as perfect as possible, all the weak wood should be cut out entirely8, and all the strong wood formed the last season should be cut down to two eyes. The knife should always be applied9 directly above a bud, and sloping upward from it. The preceding observations apply principally to rose bushes, or dwarf roses; with pillar, climbing, and tree roses, the practice should be somewhat different. The former two need comparatively little pruning; they require careful thinning out, but should seldom be shortened. The very young side shoots can sometimes be shortened in, to prevent the foliage from becoming too thick and crowded.

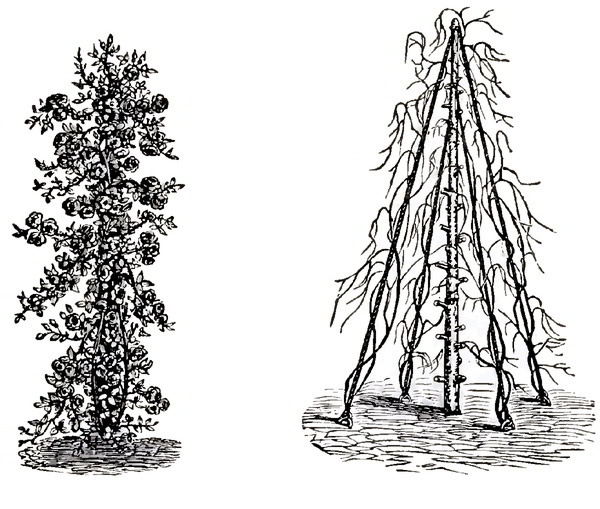

Pillars for roses can be made of trellis work, of iron rods in different forms, or of wood, but they should enclose a space of at least a foot in diameter. The cheapest plan, and one that will last many years, is to make posts of about 1? or 2 inches square, out of locust10 or pitch-pine plank11, and connect them with common hoop-iron. They should be the length of a plank—between twelve and thirteen feet—and should be set three feet in the ground, that they may effectually resist the action of the wind. The Rose having been cut down to the ground, is planted inside of the pillar, and will make strong growths the first season. As the leading shoots appear, they[Pg 95] should be trained spirally around the outside of the pillar, and sufficiently12 near each other to enable them to fill up the intermediate space with their foliage. These leading shoots will then form the permanent wood, and the young side shoots, pruned in from year to year, will produce the flowers, and at the flowering season cover the whole pillar with a mass of rich and showy bloom. Figure 5 gives the appearance of a pillar of this kind. If the tops of the leading shoots die down at all, they should be shortened down to the first strong eye, because, if a weak bud is left at the top, its growth will be slender for a long time. The growth of different varieties of roses is very varied14; some make delicate shoots, and require little room, while others, like the Queen of the Prairies, are exceedingly robust15, and may require a larger pillar than the size we have mentioned. Figure 6 shows the method of constructing a pyramid by the use of a central post and iron rods.

Fig13. 5.—PILLAR ROSE. Fig. 6.—ROSE PYRAMID.

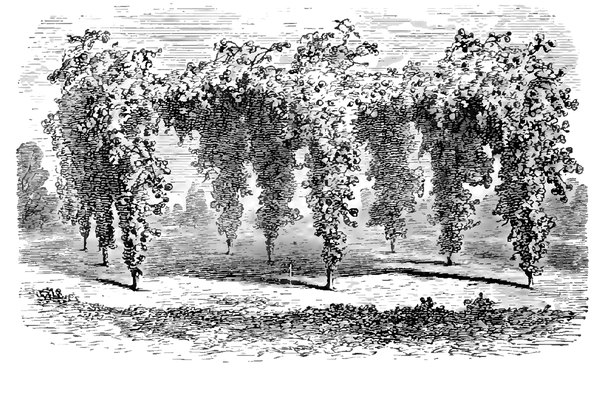

Climbing roses require very much the same treatment as pillar roses, and are frequently trained over arches, or in festoons from one pillar to another. In these the weak branches should also be thinned out, and the strong ones be allowed to remain, without being shortened, as in these an abundant bloom is wanted, rather than large flowers. An arbor16, made by training roses from one pillar to another, is represented in figure 7. In training climbing roses over any flat surface, as a trellis, wall, or side of a house, the principal point is so to place the leading shoots that all the intermediate space may be filled up with foliage. They can either be trained in fan-shape, with side shoots growing out from a main stem, or one leading shoot can be encouraged and trained in parallel horizontal lines to the top, care being taken to preserve sufficient intermediate space for the foliage. Where no shoots are wanted, the buds can be rubbed off before they push out. No weak shoots should be allowed to grow from the bottom, but all the strong ones should be allowed to grow as much as they may. When the intermediate space is filled with young wood and[Pg 97] foliage, all the thin, small shoots should be cut out every year, and the strongest buds only allowed to remain, which, forming strong branches, will set closely to the wall and preserve a neat appearance.

The production of roses out of season, by forcing, was, as we have shown, well known to the ancient Romans, and from them has been handed down to the present time. But the retarding17 of roses by means of a regular process of pruning owes its origin to a comparatively modern date. This process is mentioned both by Lord Bacon and Sir Robert Boyle. The latter says: “It is delivered by the Lord Verulam, and other naturalists18, that if a rose bush be carefully cut as soon as it is done bearing in the summer, it will again bear roses in the autumn. Of this, many have made unsuccessful trials, and thereupon report the affirmation to be false; yet I am very apt to think that my lord was encouraged by experience to write as he did. For, having been particularly solicitous19 about the experiment, I find by the relation, both of my own and other experienced gardeners, that this way of procuring20 autumnal roses will, in most rose bushes, commonly fail, but succeed in some that are good bearers; and, accordingly, having this summer made trial of it, I find that of a row of bushes cut in June, by far the greater number promise no autumnal roses; but one that hath manifested itself to be of a vigorous and prolific21 nature is, at this present, indifferently well stored with those of the damask kind. There may, also, be a mistake in the species of roses; for experienced gardeners inform me that the Musk22 Rose will, if it be a lusty plant, bear flowers in autumn without cutting; and, therefore, that may unjustly be ascribed to art, which is the bare production of nature.” Thus, in quaint23 and ancient style, discourses24 the wise and pious25 philosopher on our favorite flower, and also mentions the fact, that a red rose becomes white on being exposed to the fumes26 of sulphur. This, however,[Pg 98] had been observed before Sir Robert’s time. Notwithstanding his doubts, it is now a well-established fact, that the blooming of roses may be retarded27 by cutting them back to two eyes after they have fairly commenced growing, and the flower buds are discoverable. A constant succession can be obtained where there is a number of plants, by cutting each one back a shorter or longer distance, or at various periods of its growth. In these cases, however, it very often will not bloom until autumn, because the second effort to produce flowers is much greater than the first, and is not attended with success until late in the season.

However desirable may be this retarding process, it cannot be relied on as a general practice, because the very unusual exertion28 made to produce the flowers a second time, weakens the plant, and materially affects its prosperity the subsequent year.

There is, indeed, but one kind of summer pruning that is advantageous29, which is the thinning out of the flower-buds as soon as they appear, in order that the plant may be burdened with no more than it can fully5 perfect, and the cutting off all the seed vessels30 after the flower has expanded and the petals31 have fallen. Until this last is done, a second bloom cannot readily be obtained from the Bengal Rose and its sub-classes, the Tea and Noisette, which otherwise grow and bloom constantly throughout the season.

We would impress upon our readers the absolute, the essential, importance of cultivation32—of constantly stirring the soil in which the Rose is planted; and we scarcely know of more comprehensive directions in a few words than the reply of an experienced horticulturist to one who asked the best mode of growing fine fruits and flowers. The old gentleman replied that the mode could be described in three words, “cultivate, cultivate, cultivate.” After the same manner, we would impress the importance[Pg 99] of these three words upon all those who love well-grown and beautiful roses. They are, indeed, multum in parvo—the very essence of successful culture. The soil cannot be plowed33, dug, or stirred too much; it should be dug and hoed, not merely to keep down the weeds, but to ensure the health and prosperity of the plant. Cultivation is to all plants and trees manure34, sun, and rain. It opens the soil to the nutrition it may receive from the atmosphere, to the beneficial influence of light, and to the morning and evening dew. It makes the heavy soil light, and the light soil heavy; if the earth is saturated35 with rain, it dries it; if burned up with drought, it moistens it. Watering is often beneficial, and is particularly so to roses just before and during the period of bloom; but in an extremely dry season, if we were obliged to choose between the watering-pot and the spade, we should most unhesitatingly give the preference to the latter.

We do not wish, however, to undervalue the benefits of water. If the plants are well mulched with straw, salt hay, or any other litter, frequent watering is very beneficial. When not mulched, the watering should always be followed by the hoe, in order to destroy the baking of the surface. While the plants are in a growing state, liquid manure will give a larger and a finer bloom. This liquid manure may be made with soapsuds, or the refuse from the house. When these are not easily obtained, half a bushel of cow or horse dung can be placed in a barrel, which can then be filled with water, well stirred up, and allowed to settle a day or two before being used.

For those who are willing to incur36 the expense, a very nice way of applying pure water is to sink ordinary tile, two inches in diameter, with collars, about a foot below the surface, around and through the rose bed. An elbow from this, coming to the surface, can convey the water into the pipes, through the joints37 of which it will escape,[Pg 100] and thus irrigate38 the whole ground, without baking the surface.

BEDDING ROSES.

While Remontant, Moss39, and Garden Roses are adapted to the wants of much the larger number of growers, because they require no protection in winter, and are strong and robust in their growth and habit, yet the ever-blooming varieties are becoming daily more popular. While but few of the Remontants have more than two seasons of distinct and abundant bloom, the Teas, Chinas, and Noisettes, bloom constantly and continuously. In grace, and color, and beauty, these last have more varied charms than the more hardy and abundant Remontants, and the difficulty of caring for them in the winter, even by those who have no glass, is compensated40 by the additional pleasure they give in the summer. Those who have glass can enjoy them winter and summer alike. Their superiority in constant blooming, especially, adapts them for planting in masses or beds scattered41 about the lawn. These beds can be each of one color, or they can be assorted42, or can be planted in the ribbon style, rows of white, or red, or yellow alternating. No bedding flowers, Verbenas, Salvias, or any other plant, will give so constant pleasure as Roses. They can be purchased, also, nearly as cheaply as ordinary bedding plants, and are found in several places as low as $15 per 100, or $100 per 1,000. On being taken out of the pots they will grow rapidly, and bloom after they are thoroughly43 established, and afterward44, year after year, they will commence blooming early, and continue until frost. A bed made in any part of the lawn, and in any soil, will grow them well, provided it has a dry bottom, and has some well-decomposed manure dug in it. A light, sandy soil will grow them in the greatest perfection. They can be planted eighteen inches to two feet apart,[Pg 101] and the new shoots, as soon as they have attained sufficient length, should be pegged45 down, so as to cover the whole ground. The branches thus laid down will give abundant flowers throughout their whole length, and from each bud a strong-rooted shoot will be thrown up, and being pruned down close in the autumn, will be ready to produce a strong and bearing shoot another year. If they become too close and crowded, the new shoots can be partially46 cut away. North of Baltimore, these Roses will need protection in the winter. This can be done by covering the bed with sand, several inches deep, or by taking up the plants, cutting them down, heeling them in in a dry cellar, or potting them for a green-house.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

pruning

|

|

| n.修枝,剪枝,修剪v.修剪(树木等)( prune的现在分词 );精简某事物,除去某事物多余的部分 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

attained

|

|

| (通常经过努力)实现( attain的过去式和过去分词 ); 达到; 获得; 达到(某年龄、水平、状况) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

dwarf

|

|

| n.矮子,侏儒,矮小的动植物;vt.使…矮小 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

foliage

|

|

| n.叶子,树叶,簇叶 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

fully

|

|

| adv.完全地,全部地,彻底地;充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

pruned

|

|

| v.修剪(树木等)( prune的过去式和过去分词 );精简某事物,除去某事物多余的部分 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

hardy

|

|

| adj.勇敢的,果断的,吃苦的;耐寒的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

entirely

|

|

| ad.全部地,完整地;完全地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

applied

|

|

| adj.应用的;v.应用,适用 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

locust

|

|

| n.蝗虫;洋槐,刺槐 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

plank

|

|

| n.板条,木板,政策要点,政纲条目 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

varied

|

|

| adj.多样的,多变化的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

robust

|

|

| adj.强壮的,强健的,粗野的,需要体力的,浓的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

arbor

|

|

| n.凉亭;树木 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

retarding

|

|

| 使减速( retard的现在分词 ); 妨碍; 阻止; 推迟 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

naturalists

|

|

| n.博物学家( naturalist的名词复数 );(文学艺术的)自然主义者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

solicitous

|

|

| adj.热切的,挂念的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

procuring

|

|

| v.(努力)取得, (设法)获得( procure的现在分词 );拉皮条 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

prolific

|

|

| adj.丰富的,大量的;多产的,富有创造力的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

musk

|

|

| n.麝香, 能发出麝香的各种各样的植物,香猫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

quaint

|

|

| adj.古雅的,离奇有趣的,奇怪的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

discourses

|

|

| 论文( discourse的名词复数 ); 演说; 讲道; 话语 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

pious

|

|

| adj.虔诚的;道貌岸然的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

fumes

|

|

| n.(强烈而刺激的)气味,气体 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

retarded

|

|

| a.智力迟钝的,智力发育迟缓的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

exertion

|

|

| n.尽力,努力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

advantageous

|

|

| adj.有利的;有帮助的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

vessels

|

|

| n.血管( vessel的名词复数 );船;容器;(具有特殊品质或接受特殊品质的)人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

petals

|

|

| n.花瓣( petal的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

cultivation

|

|

| n.耕作,培养,栽培(法),养成 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

plowed

|

|

| v.耕( plow的过去式和过去分词 );犁耕;费力穿过 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

manure

|

|

| n.粪,肥,肥粒;vt.施肥 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

saturated

|

|

| a.饱和的,充满的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

incur

|

|

| vt.招致,蒙受,遭遇 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

joints

|

|

| 接头( joint的名词复数 ); 关节; 公共场所(尤指价格低廉的饮食和娱乐场所) (非正式); 一块烤肉 (英式英语) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

irrigate

|

|

| vt.灌溉,修水利,冲洗伤口,使潮湿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

moss

|

|

| n.苔,藓,地衣 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

compensated

|

|

| 补偿,报酬( compensate的过去式和过去分词 ); 给(某人)赔偿(或赔款) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

scattered

|

|

| adj.分散的,稀疏的;散步的;疏疏落落的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

assorted

|

|

| adj.各种各样的,各色俱备的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

thoroughly

|

|

| adv.完全地,彻底地,十足地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

afterward

|

|

| adv.后来;以后 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

pegged

|

|

| v.用夹子或钉子固定( peg的过去式和过去分词 );使固定在某水平 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

partially

|

|

| adv.部分地,从某些方面讲 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |