When his countrymen heard the story of this daring and successful cruise, Jones immediately became the most famous officer of the new navy. The éclat he had gained by his brilliant voyage at once raised him from a more or less obscure position, and gave him a great reputation in the eyes of his countrymen, a reputation he did not thereafter lose. But Jones was not a man to live upon a reputation. He had scarcely arrived at Providence1 before he busied himself with plans for another undertaking2. He had learned from prisoners taken on his last cruise that there were a number of American prisoners, at various places, who were undergoing hard labor3 in the coal mines of Cape4 Breton Island, and he conceived the bold design of freeing them if possible.

We are here introduced to one striking characteristic, not the least noble among many, of this great man. The appeal of the prisoner always profoundly touched his heart. The freedom of his nature, his own passionate5 love for liberty and independence, the heritage of his Scotch6 hills perhaps, ever made him anxious and solicitous7 about those who languished8 in captivity9. It was but the working out of that spirit which compelled him to relinquish10 his participation11 in the lucrative12 slave trade. In all his public actions, he kept before him as one of his principal objects the release of such of his countrymen as were undergoing the horrors of British prisons.

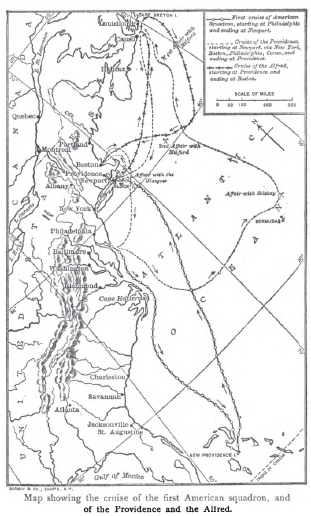

Map showing the cruise of the first American squadron,

and of the Providence and the Alfred.

and of the Providence and the Alfred.

The suggested enterprise found favor in the mind of Commodore Hopkins, who forthwith assigned Jones to the command of a squadron comprising the Alfred, the Providence, and the brigantine Hampden. Jones hoisted13 his flag on board the Alfred and hastened his preparations for departure. He found the greatest difficulty in manning his little squadron, and finally, in despair of getting a sufficient crew to man them all, he determined14 to set sail with the Alfred and the Hampden only, the latter vessel15 being commanded by Captain Hoysted Hacker16. He received his orders on the 22d of October, and on the 27th the two vessels17 got under way from Providence. The wind was blowing fresh at the time, and Hacker, who seems to have been an indifferent sailor, ran the Hampden on a ledge18 of rock, where she was so badly wrecked19 as to be unseaworthy. Jones put back to his anchorage, and, having transferred the crew of the Hampden to the Providence, set sail on the 2d of November.

Both vessels were very short-handed. The Alfred, whose proper complement20 was about three hundred, which had sailed from Philadelphia with two hundred and thirty-five, now could muster21 no more than one hundred and fifty all told. The two vessels were short of water, provisions, munitions22, and everything else that goes to make up a ship of war. Jones made up for all this deficiency by his own personality.

On the evening of the first day out the two vessels anchored in Tarpauling Cove23, near Nantucket. There they found a Rhode Island privateer at anchor. In accordance with the orders of the commodore, Jones searched her for deserters, and from her took four men on board the Alfred. He was afterward24 sued in the sum of ten thousand pounds for this action, but, though the commodore, as he stated, abandoned him in his defense25, nothing came of the suit.

On the 3d of November, by skillful and successful maneuvering26, the two ships passed through the heavy British fleet off Block Island, and squared away for the old cruising ground on the Grand Banks. In addition to the release of the prisoners there was another object in the cruise. A squadron of merchant vessels loaded with coal for the British army in New York was about to leave Louisburg under convoy27. Jones determined to intercept28 them if possible.

On the 13th, off Cape Canso again, the Alfred encountered the British armed transport Mellish, of ten guns, having on board one hundred and fifty soldiers. After a trifling29 resistance she was captured. She was loaded with arms, munitions of war, military supplies, and ten thousand suits of winter clothing, destined30 for Sir Guy Carleton's army in Canada. She was the most valuable prize which had yet fallen into the hands of the Americans. The warm clothing, especially, would be a godsend to the ragged31, naked army of Washington. Of so much importance was this prize that Jones determined not to lose sight of her, and to convoy her into the harbor himself. Putting a prize crew on board, he gave instructions that she was to be scuttled32 if there appeared any danger of her recapture.

About this time two other vessels were captured, one of which was a large fishing vessel, from which he was able to replenish33 his meager34 store of provisions. On the 14th of November a severe gale35 blew up from the northwest, accompanied by a violent snowstorm. Captain Hacker bore away to the southward before the storm and parted company during the night, returning incontinently to Newport. The weather continued execrable. Amid blinding snowstorms and fierce winter gales36 the Alfred and her prizes beat up along the desolate37 iron-bound shore. Jones again entered the harbor of Canso, and, finding a large English transport laden38 with provisions for the army aground on a shoal near the mouth of the harbor, sent a boat party which set her on fire. Seeing an immense warehouse39 filled with oil and material for whale and cod40 fisheries, the boats made a sudden dash for the shore, and, applying a torch to the building, it was soon consumed.

Beating off the shore, still accompanied by his prizes, he continued up the coast of Cape Breton toward Louisburg, looking for the coal fleet. It was his good fortune to run across it in a dense41 fog. It consisted of a number of vessels under the convoy of the frigate42 Flora43, a ship which would have made short work of him if she could have run across him. Favored by the impenetrable fog, with great address and hardihood Jones succeeded in capturing no less than three of the convoy, and escaped unnoticed with his prizes.

Two days afterward he came across a heavily armed British privateer from Liverpool, which he took after a slight resistance. But now, when he attempted to make Louisburg to carry out his design of levying44 on the place and releasing the prisoners, he found that the harbor was closed by masses of ice, and that it was impossible to effect a landing. Indeed, his ships were in a perilous45 condition already. He had manned no less than six prizes, which had reduced his short crew almost to a prohibitive degree. On board the Alfred he had over one hundred and fifty prisoners, a number greatly in excess of his own men; his water casks were nearly empty, and his provisions were exhausted46. He had six prizes with him, one of exceptional value. Nothing could be gained by lingering on the coast, and he decided47, therefore, to return.

The little squadron, under convoy of the Alfred and the armed privateer, which he had manned and placed under the command of Lieutenant48 Saunders, made its way toward the south in the fierce winter weather. Off St. George's Bank they again encountered the Milford. It was late in the afternoon when her topsails rose above the horizon. The wind was blowing fresh from the northwest; the Alfred and her prizes were on the starboard tack49, the enemy was to windward. From his previous experience Jones was able fairly to estimate the speed of the Milford. A careful examination convinced him that it would be impossible for the latter to close with his ships before nightfall. He therefore placed the Alfred and the privateer between the English frigate lasking down upon them and the rest of his ships, and continued his course. He then signaled the prizes, with the exception of the privateer, that they should disregard any orders or signals which he might give in the night, and hold on as they were.

The prizes were slow sailers, and, as the slowest necessarily set the pace for the whole squadron, the Milford gradually overhauled50 them. At the close of the short winter day, when the night fell and the darkness rendered sight of the pursued impossible, Jones showed a set of lantern signals, and, hanging a top light on the Alfred, right where it would be seen by the Englishmen, at midnight, followed by the privateer, he changed his course directly away from the prizes. The Milford promptly51 altered her course and pursued the light. The prizes, in obedience52 to their orders, held on as they were. At daybreak the prizes were nowhere to be seen, and the Milford was booming along after the privateer and the Alfred.

To run was no part of Paul Jones' desires, and he determined to make a closer inspection53 of the Milford, with a view to engaging if a possibility of capturing her presented itself; so he bore up and headed for the oncoming British frigate. The privateer did the same. A nearer view, however, developed the strength of the enemy, and convinced him that it would be madness to attempt to engage with the Alfred and the privateer in the condition he then was, so he hauled aboard his port tacks54 once more, and, signaling to the privateer, stood off again. For some reason--Jones imagined that it was caused by a mistaken idea of the strength of the Milford--Saunders signaled to Jones that the Milford was of inferior force, and disregarding his orders foolishly ran down under her lee from a position of perfect safety, and was captured without a blow. The lack of proper subordination in the nascent55 navy of the United States brought about many disasters, and this was one of them. Jones characterized this as an act of folly56; it is difficult to dismiss it thus mildly. I would fain do no man an injustice57, but if a man wanted to be a traitor58 that is the way he would act. Jones' own account of this adventure, which follows, is of deep interest:

"This led the Milford entirely59 out of the way of the prizes, and particularly the clothing ship, Mellish, for they were all out of sight in the morning. I had now to get out of the difficulty in the best way I could. In the morning we again tacked60, and as the Milford did not make much appearance I was unwilling61 to quit her without a certainty of her superior force. She was out of shot, on the lee quarter, and as I could only see her bow, I ordered the letter of marque, Lieutenant Saunders, that held a much better wind than the Alfred, to drop slowly astern, until he could discover by a view of the enemy's side whether she was of superior or inferior force, and to make a signal accordingly. On seeing Mr. Saunders drop astern, the Milford wore suddenly and crowded sail toward the northeast. This raised in me such doubts as determined me to wear also, and give chase. Mr. Saunders steered62 by the wind, while the Milford went lasking, and the Alfred followed her with a pressed sail, so that Mr. Saunders was soon almost hull63 down to windward. At last the Milford tacked again, but I did not tack the Alfred till I had the enemy's side fairly open, and could plainly see her force. I then tacked about ten o'clock. The Alfred being too light to be steered by the wind, I bore away two points, while the Milford steered close by the wind, to gain the Alfred's wake; and by that means he dropped astern, notwithstanding his superior sailing. The weather, too, which became exceedingly squally, enabled me to outdo the Milford by carrying more sail. I began to be under no apprehension64 from the enemy's superiority, for there was every appearance of a severe gale, which really took place in the night. To my great surprise, however, Mr. Saunders, toward four o'clock, bore down on the Milford, made the signal of her inferior force, ran under her lee, and was taken!"

With the exception of one small vessel, which was recaptured, the prizes all arrived safely, the precious Mellish finally reaching the harbor of Dartmouth. The Alfred dropped anchor at Boston, December 15, 1776. The news of the captured clothing reached Washington and gladdened his heart--and the hearts of his troops as well--on the eve of the battle of Trenton.

The reward for this brilliant and successful cruise, the splendid results of which had been brought about by the most meager means, was an order relieving him of the command of the Alfred and assigning him to the Providence again. When he arrived at Philadelphia the next spring he found that by an act of Congress, on the 10th of October, 1776, which had created a number of captains in the navy, he, who had been first on the list of lieutenants65, and therefore the sixth ranking sea officer, was now made the eighteenth captain. He was passed over by men who had no claim whatever to superiority on the score of their service to the Commonwealth66, which had been inconsiderable or nothing at all. Indeed, there was no man in the country who by merit or achievement was entitled to precede him, except possibly Nicholas Biddle.

If the friendless Scotsman had commanded more influence, more political prestige, so that he might have been rewarded for his auspicious67 services by placing him at the head of the navy, I venture to believe that some glorious chapters in our marine68 history would have been written.

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

providence

|

|

| n.深谋远虑,天道,天意;远见;节约;上帝 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

undertaking

|

|

| n.保证,许诺,事业 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

labor

|

|

| n.劳动,努力,工作,劳工;分娩;vi.劳动,努力,苦干;vt.详细分析;麻烦 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

cape

|

|

| n.海角,岬;披肩,短披风 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

passionate

|

|

| adj.热情的,热烈的,激昂的,易动情的,易怒的,性情暴躁的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

scotch

|

|

| n.伤口,刻痕;苏格兰威士忌酒;v.粉碎,消灭,阻止;adj.苏格兰(人)的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

solicitous

|

|

| adj.热切的,挂念的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

languished

|

|

| 长期受苦( languish的过去式和过去分词 ); 受折磨; 变得(越来越)衰弱; 因渴望而变得憔悴或闷闷不乐 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

captivity

|

|

| n.囚禁;被俘;束缚 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

relinquish

|

|

| v.放弃,撤回,让与,放手 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

participation

|

|

| n.参与,参加,分享 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

lucrative

|

|

| adj.赚钱的,可获利的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

hoisted

|

|

| 把…吊起,升起( hoist的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

determined

|

|

| adj.坚定的;有决心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

vessel

|

|

| n.船舶;容器,器皿;管,导管,血管 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

hacker

|

|

| n.能盗用或偷改电脑中信息的人,电脑黑客 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

vessels

|

|

| n.血管( vessel的名词复数 );船;容器;(具有特殊品质或接受特殊品质的)人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

ledge

|

|

| n.壁架,架状突出物;岩架,岩礁 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

wrecked

|

|

| adj.失事的,遇难的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

complement

|

|

| n.补足物,船上的定员;补语;vt.补充,补足 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

muster

|

|

| v.集合,收集,鼓起,激起;n.集合,检阅,集合人员,点名册 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

munitions

|

|

| n.军火,弹药;v.供应…军需品 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

cove

|

|

| n.小海湾,小峡谷 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

afterward

|

|

| adv.后来;以后 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

defense

|

|

| n.防御,保卫;[pl.]防务工事;辩护,答辩 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

maneuvering

|

|

| v.移动,用策略( maneuver的现在分词 );操纵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

convoy

|

|

| vt.护送,护卫,护航;n.护送;护送队 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

intercept

|

|

| vt.拦截,截住,截击 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

trifling

|

|

| adj.微不足道的;没什么价值的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

destined

|

|

| adj.命中注定的;(for)以…为目的地的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

ragged

|

|

| adj.衣衫褴褛的,粗糙的,刺耳的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

scuttled

|

|

| v.使船沉没( scuttle的过去式和过去分词 );快跑,急走 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

replenish

|

|

| vt.补充;(把…)装满;(再)填满 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

meager

|

|

| adj.缺乏的,不足的,瘦的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

gale

|

|

| n.大风,强风,一阵闹声(尤指笑声等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

gales

|

|

| 龙猫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

desolate

|

|

| adj.荒凉的,荒芜的;孤独的,凄凉的;v.使荒芜,使孤寂 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

laden

|

|

| adj.装满了的;充满了的;负了重担的;苦恼的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

warehouse

|

|

| n.仓库;vt.存入仓库 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

cod

|

|

| n.鳕鱼;v.愚弄;哄骗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

dense

|

|

| a.密集的,稠密的,浓密的;密度大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

frigate

|

|

| n.护航舰,大型驱逐舰 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

flora

|

|

| n.(某一地区的)植物群 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

levying

|

|

| 征(兵)( levy的现在分词 ); 索取; 发动(战争); 征税 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

perilous

|

|

| adj.危险的,冒险的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

exhausted

|

|

| adj.极其疲惫的,精疲力尽的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

decided

|

|

| adj.决定了的,坚决的;明显的,明确的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

lieutenant

|

|

| n.陆军中尉,海军上尉;代理官员,副职官员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

tack

|

|

| n.大头钉;假缝,粗缝 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

overhauled

|

|

| v.彻底检查( overhaul的过去式和过去分词 );大修;赶上;超越 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

promptly

|

|

| adv.及时地,敏捷地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

obedience

|

|

| n.服从,顺从 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

inspection

|

|

| n.检查,审查,检阅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

tacks

|

|

| 大头钉( tack的名词复数 ); 平头钉; 航向; 方法 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

nascent

|

|

| adj.初生的,发生中的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

folly

|

|

| n.愚笨,愚蠢,蠢事,蠢行,傻话 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

injustice

|

|

| n.非正义,不公正,不公平,侵犯(别人的)权利 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

traitor

|

|

| n.叛徒,卖国贼 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

entirely

|

|

| ad.全部地,完整地;完全地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

tacked

|

|

| 用平头钉钉( tack的过去式和过去分词 ); 附加,增补; 帆船抢风行驶,用粗线脚缝 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

unwilling

|

|

| adj.不情愿的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

steered

|

|

| v.驾驶( steer的过去式和过去分词 );操纵;控制;引导 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

hull

|

|

| n.船身;(果、实等的)外壳;vt.去(谷物等)壳 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

apprehension

|

|

| n.理解,领悟;逮捕,拘捕;忧虑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

lieutenants

|

|

| n.陆军中尉( lieutenant的名词复数 );副职官员;空军;仅低于…官阶的官员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

commonwealth

|

|

| n.共和国,联邦,共同体 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

auspicious

|

|

| adj.吉利的;幸运的,吉兆的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

marine

|

|

| adj.海的;海生的;航海的;海事的;n.水兵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |