As with the water-wheel, so its congener, the windmill, beloved of artists, is going. A motive power as cheap as water is the wind, but, unfortunately, it is not so reliable. It is believed that the Chinese were the first to use the wind as a motive power for mills, and we have no record as to when they were introduced into Europe; we only know they were in use in the twelfth century. As a rule, in England, windmills have four arms, or ‘whips,’ but sometimes they104 have six. These arms are generally covered with strong canvas, but occasionally they are covered with thin boarding; they are set at an angle, which varies according to the fancy of the miller14, but the shaft15 to which they are attached (called the ‘wind shaft’) is invariably placed at an inclination16 of 10 or 15 degrees, in order that the revolving17 arms should clear the bottom portion of the mill.

A Post Mill.

A Water-Wheel Mill.

The oldest kind of windmill is called a post mill, 105

106because the whole structure is centred on a post, or pivot18, and, when the wind shifts, the mill has to be turned bodily to meet it, by means of a long lever. The smock, or frock, windmill is an improvement upon the post mill; the building itself is stationary19 and permanent, but the head or cap, where is the wind shaft, rotates, and this is more easily managed.

For hundreds of years people were contented20 with the four and six arms to their windmills, and it was only in modern times that Messrs. J. Warner and Sons, of Cripplegate, London, patented their annular21 sails, which, as is plain to the meanest capacity, are vastly superior. The shutters22, or ‘vanes,’ are connected with spiral springs, which keep them up to the best angle of ‘weather, for light winds. If the strength of the wind increases, the vanes give to the wind, forcing back the springs, and thus the area on which the wind acts diminishes. In addition, there are a striking lever and tackle for setting the vanes edgeways to the wind, when the mill is stopped, or a storm expected.

We have seen how from the very first man used stones wherewith to triturate his corn, and to this day stones are still used for grinding, although their days are in all probability numbered, and in a very little time they, with the windmill, will be relegated23 to limbo24. The Encyclop?dia Britannica gives such an excellent description of these mill-stones, that I quote it in its entirety.

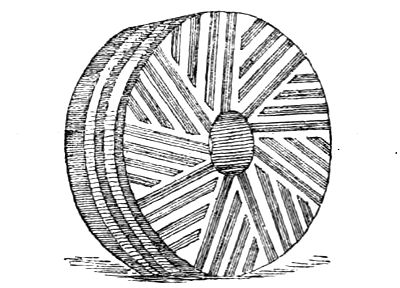

The Grinding Surface of a Millstone.

‘They consist of two flat cylindrical25 masses inclosed within a wooden or sheet metal case, the lower, or bed-stone, being permanently26 fixed27, while the upper,107 or runner, is accurately28 pivoted29 and balanced over it The average size of millstones is about four feet two inches in diameter, by twelve inches in thickness, and they are made of a hard but cellular30 siliceous stone, called buhr-stone, the best qualities of which are obtained from La-Ferté-sous-Jouarre, department of Seine et Marne, France. Millstones are generally built up of segments, bound together round the circumference31 by an iron hoop32, and backed with plaster of Paris. The bed-stone is dressed to a perfectly33 flat plane surface, and a series of grooves34, or shallow depressions, are cut in it, generally in the manner shown, which represents the grinding surface of an upper or running stone. The grooves on both are made to correspond exactly, so that when the one is rotated over the other the sharp edges of the grooves,108 meeting each other, operate like a rough pair of scissors, and thus the effect of the stones on grain submitted to their action is at once that of cutting, squeezing, and crushing. The dressing35 and grooving36 of millstones is generally done by hand picking, but sometimes black amorphous37 diamonds (carbonado) are used, and emery wheel dressers have likewise been suggested. The upper stone, or runner, is set in motion by a spindle on which it is mounted, which passes up through the centre of the bed-stone, and there are screws and other appliances for adjusting and balancing the stone. Further provision is made within the stone case for passing through air to prevent too high a heat being developed in the grinding operation, and sweepers for conveying the flour to the meal spout38 are also provided.

‘The ground meal delivered by the spout is carried forward in a conveyor, or creeper box, by means of an Archimedean screw, to the elevators, by which it is lifted to an upper floor to the bolting or flour-dressing machine. The form in which this apparatus39 was formerly40 employed consisted of a cylinder41 mounted on an inclined plane, and covered externally with wire cloth of different degrees of fineness, the finest being at the upper part of the cylinder, where the meal is admitted. Within the cylinder, which was stationary, a circular brush revolved42, by which the meal was pressed against the wire cloth, and, at the same time, carried gradually towards the lower extremity44, sifting45 out, as it proceeded, the mill products into different grades of fineness, and finally delivering the coarse bran at the extremity of the109 cylinder. For the operation of bolting or dressing, hexagonal or octagonal cylinders46, about three feet in diameter, and from 20 to 25 feet long, are now commonly employed. These are mounted horizontally on a spindle for revolving, and externally they are covered with silk of different degrees of fineness, whence they are called “silks,” or “silk dressers.” Radiating arms or other devices for carrying the meal gradually forward as the apparatus revolved, are fixed within the cylinders; and there is also an arrangement of beaters, which gives the segments of cloth a sharp tap, and thereby47 facilitates the sifting action of the apparatus. Like all other mill machines, the modifications48 of the silk dresser are numerous,’

We have seen the ordinary operation of grinding flour in the old-fashioned way; now let us notice the improvements in making wheat into flour.

‘We will suppose that the wheat has arrived by lighter49 at one of the large mills on the Thames, and that it has been shovelled50 into sacks and hoisted51 into the warehouse52. The process by which it is turned into flour may be divided into three stages: (1) cleaning, (2) breaking, (3) grinding; but the number and complexity53 of the operations included in these stages are astounding54. It must be understood that the following description refers to a first-class London mill—that is, one which has, certainly no superior, and, probably, no equal, in the world.

‘In the first stage the wheat is merely prepared for the mill, and this is done in the cleaning department, which is separate from the mill proper. From the warehouse the grain is passed to a sifter55 or “separator,110” which is a kind of sieve56. Here the grosser impurities57—straw, sticks, stones, earth, seeds, and what not—are removed. Thence to an “elevator,” precisely58 similar in principle to that previously59 described, and by the elevator straight to the top of the building. Here it enters a wire sieve in the form of a revolving hexagonal “reel,” by which the smaller heavy impurities with which it is still mixed are separated. Passing through this, it drops into the next storey, to be subjected to the “aspirator,” an apparatus by means of which currents of air are blown through the grain as it falls and carry off the lighter and more volatile60 rubbish mixed with it. In the next floor is an ingenious instrument with a special purpose. Among the wheat is still a quantity of small black seeds, known as “cockle” seeds, and to get rid of these the “cockle cylinder” is employed. It is a revolving metal cylinder, the inner surface of which is fitted with small holes; the grain passes into the interior of the cylinder, and as the latter goes round and round the cockle seeds stick in the small holes and are carried up to a certain height, when they fall out and are caught by an “apron”; while the wheat, which is too large to stick in the holes, continually falls back into the bottom of the cylinder. Again our corn drops a storey, and encounters the “decorcitator.” The object of this apparatus is to knock off the dust and dirt adhering to the grains, and it is effected by agitating61 them between two metal surfaces at a high rate of speed. The amount of dust removed by this method from apparently62 clean grain is astonishing. In the next storey is another decorcitator, and below that111 a second aspirator, which brings us once more to the ground.

‘On reaching the ground floor again, our now clean wheat is first passed through the “grading” or “sizing” reels, which separate it into two sizes, and then it enters the mill proper. It should be said here that the milling industry of the world has been revolutionised within the past few years by the substitution of steel rollers for the old millstones. The process of crushing or grinding, however, by steel rollers is accomplished63 in a very gradual manner, as will be explained: First come the “break rolls.” These are solid steel rollers set in pairs, with corrugated64 surfaces; this gives them a cutting action. Wheat is passed through five successive pairs of these rollers. The first are about 1/16th inch apart, and only break or bruise65 the grain slightly. Each successive pair is set closer, and carries the bruising66 a step further. But this is only half the business. After each set of rollers the grain goes through a “purifier,” which is either a sieve of some kind or an aspirator, or both together, and the object is always the same—namely, to separate the solid particles of the broken wheat from the lighter ones. The former are, or rather will eventually be, flour; the latter constitute “offal.” And the whole art of milling is merely an extension of this process; first reduction, then separation, repeated over and over again. As the grain passes through each successive set of rollers it is broken up finer and ever finer, and the separating action of the “purifier” accompanies it step by step. The solid particles grow smaller and smaller, the112 “offal” correspondingly finer and finer. This is the process in brief, but there are endless complications and refinements67 on the way. For instance, the solid particles are not only separated but are themselves divided into groups according to size. Then the offal often undergoes a further purifying process. Then the purifiers differ—some are complex, others simple; some of wire, others of silk; some revolve43, others oscillate; some are “aspirated,” others not; and so forth68. Meanwhile, at the end of the five rolls and five purifiers, which make up our breaking department, we have got three products: (a) semolina; (b) middlings; (c) offal. The first two are practically varieties of the same—i.e., both solid particles, which will afterwards be flour, but of different sizes. They are half way between grain and flour—hence the term “middlings.”

‘Grinding is only a continuation of the above process, but the rollers are different; their surfaces are smooth, and they are set closer together. The purifiers, too, are, for the most part, more elaborate. A look at one of them will show the extreme ingenuity69 expended70 on these operations. It consists primarily of an oscillating sieve made of silk, through the meshes71 of which the particles of flour fall into a wooden bin13. On the floor of the bin is a “worm” which continually works the flour along to one end; on the under surface of the sieve is a travelling brush which brushes off the adhering flour and prevents the meshes from getting clogged72. Above the sieve is an apparatus which, with the aid of currents blown by an aspirator, catches the volatile offal; and above113 that again a travelling blanket which arrests the still more volatile particles. Finally, the blanket, as it reaches the end, is tapped automatically to knock out what has stuck to it. By the time a handful of grain has been converted into a handful of fine flour it has gone through some 50 different machines, including 18 sets of rollers and 18 purifiers.

‘The following points may be of interest: A first-class London mill working 100 sets of rollers can turn out 45 sacks of flour per hour. Offal, according to its fineness or coarseness, forms bran, pollard, etc., and is worth from 5l. to 6l. a ton. The qualities of flour are whiteness and strength. The former is tested by the eye, the latter only really by baking capacity. There seems to be a general consensus73 of opinion in favour of flour made from Hungarian wheat. The best English is of sweeter flavour, but lacks “strength.” It has been reckoned that 300 sacks are made per hour in London mills, all of which is consumed in London. The flour mill industry owes nothing to American inventive genius; on the contrary, that country is behind the times. The steel rollers came originally from Hungary—always a great milling country.’

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

barley

|

|

| n.大麦,大麦粒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

primitive

|

|

| adj.原始的;简单的;n.原(始)人,原始事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

noted

|

|

| adj.著名的,知名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

pestle

|

|

| n.杵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

mortar

|

|

| n.灰浆,灰泥;迫击炮;v.把…用灰浆涂接合 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

motive

|

|

| n.动机,目的;adv.发动的,运动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

mules

|

|

| 骡( mule的名词复数 ); 拖鞋; 顽固的人; 越境运毒者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

brook

|

|

| n.小河,溪;v.忍受,容让 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

picturesque

|

|

| adj.美丽如画的,(语言)生动的,绘声绘色的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

drowsy

|

|

| adj.昏昏欲睡的,令人发困的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

murmur

|

|

| n.低语,低声的怨言;v.低语,低声而言 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

erect

|

|

| n./v.树立,建立,使竖立;adj.直立的,垂直的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

bin

|

|

| n.箱柜;vt.放入箱内;[计算机] DOS文件名:二进制目标文件 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

miller

|

|

| n.磨坊主 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

shaft

|

|

| n.(工具的)柄,杆状物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

inclination

|

|

| n.倾斜;点头;弯腰;斜坡;倾度;倾向;爱好 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

revolving

|

|

| adj.旋转的,轮转式的;循环的v.(使)旋转( revolve的现在分词 );细想 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

pivot

|

|

| v.在枢轴上转动;装枢轴,枢轴;adj.枢轴的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

stationary

|

|

| adj.固定的,静止不动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

contented

|

|

| adj.满意的,安心的,知足的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

annular

|

|

| adj.环状的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

shutters

|

|

| 百叶窗( shutter的名词复数 ); (照相机的)快门 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

relegated

|

|

| v.使降级( relegate的过去式和过去分词 );使降职;转移;把…归类 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

limbo

|

|

| n.地狱的边缘;监狱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

cylindrical

|

|

| adj.圆筒形的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

permanently

|

|

| adv.永恒地,永久地,固定不变地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

fixed

|

|

| adj.固定的,不变的,准备好的;(计算机)固定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

accurately

|

|

| adv.准确地,精确地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

pivoted

|

|

| adj.转动的,回转的,装在枢轴上的v.(似)在枢轴上转动( pivot的过去式和过去分词 );把…放在枢轴上;以…为核心,围绕(主旨)展开 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

cellular

|

|

| adj.移动的;细胞的,由细胞组成的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

circumference

|

|

| n.圆周,周长,圆周线 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

hoop

|

|

| n.(篮球)篮圈,篮 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

grooves

|

|

| n.沟( groove的名词复数 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏v.沟( groove的第三人称单数 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

dressing

|

|

| n.(食物)调料;包扎伤口的用品,敷料 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

grooving

|

|

| n.(轧辊)孔型设计v.沟( groove的现在分词 );槽;老一套;(某种)音乐节奏 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

amorphous

|

|

| adj.无定形的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

spout

|

|

| v.喷出,涌出;滔滔不绝地讲;n.喷管;水柱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

apparatus

|

|

| n.装置,器械;器具,设备 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

formerly

|

|

| adv.从前,以前 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

cylinder

|

|

| n.圆筒,柱(面),汽缸 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

revolved

|

|

| v.(使)旋转( revolve的过去式和过去分词 );细想 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

revolve

|

|

| vi.(使)旋转;循环出现 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

extremity

|

|

| n.末端,尽头;尽力;终极;极度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

sifting

|

|

| n.筛,过滤v.筛( sift的现在分词 );筛滤;细查;详审 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

cylinders

|

|

| n.圆筒( cylinder的名词复数 );圆柱;汽缸;(尤指用作容器的)圆筒状物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

thereby

|

|

| adv.因此,从而 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

modifications

|

|

| n.缓和( modification的名词复数 );限制;更改;改变 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

lighter

|

|

| n.打火机,点火器;驳船;v.用驳船运送;light的比较级 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

shovelled

|

|

| v.铲子( shovel的过去式和过去分词 );锹;推土机、挖土机等的)铲;铲形部份 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

hoisted

|

|

| 把…吊起,升起( hoist的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

warehouse

|

|

| n.仓库;vt.存入仓库 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

complexity

|

|

| n.复杂(性),复杂的事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

astounding

|

|

| adj.使人震惊的vt.使震惊,使大吃一惊astound的现在分词) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

sifter

|

|

| n.(用于筛撒粉状食物的)筛具,撒粉器;滤器;罗圈;罗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

sieve

|

|

| n.筛,滤器,漏勺 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

impurities

|

|

| 不纯( impurity的名词复数 ); 不洁; 淫秽; 杂质 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

precisely

|

|

| adv.恰好,正好,精确地,细致地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

previously

|

|

| adv.以前,先前(地) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

volatile

|

|

| adj.反复无常的,挥发性的,稍纵即逝的,脾气火爆的;n.挥发性物质 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

agitating

|

|

| 搅动( agitate的现在分词 ); 激怒; 使焦虑不安; (尤指为法律、社会状况的改变而)激烈争论 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

apparently

|

|

| adv.显然地;表面上,似乎 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

accomplished

|

|

| adj.有才艺的;有造诣的;达到了的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

corrugated

|

|

| adj.波纹的;缩成皱纹的;波纹面的;波纹状的v.(使某物)起皱褶(corrugate的过去式和过去分词) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

bruise

|

|

| n.青肿,挫伤;伤痕;vt.打青;挫伤 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

bruising

|

|

| adj.殊死的;十分激烈的v.擦伤(bruise的现在分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

refinements

|

|

| n.(生活)风雅;精炼( refinement的名词复数 );改良品;细微的改良;优雅或高贵的动作 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

forth

|

|

| adv.向前;向外,往外 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

ingenuity

|

|

| n.别出心裁;善于发明创造 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

expended

|

|

| v.花费( expend的过去式和过去分词 );使用(钱等)做某事;用光;耗尽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

meshes

|

|

| 网孔( mesh的名词复数 ); 网状物; 陷阱; 困境 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

clogged

|

|

| (使)阻碍( clog的过去式和过去分词 ); 淤滞 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

consensus

|

|

| n.(意见等的)一致,一致同意,共识 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |