Although Newton delivered a course of lectures on optics in the University of Cambridge in the years 1669, 1670, and 1671, containing his principal discoveries relative to the different refrangibility of light, yet it is a singular circumstance, that these discoveries should not have become public through the conversation or correspondence of his pupils. The Royal Society had acquired no knowledge of them till the beginning of 1672, and his reputation in that body was founded chiefly on his reflecting telescope. On the 23d December, 1671, the celebrated2 Dr. Seth Ward3, Lord Bishop4 of Sarum, who was the author of several able works on astronomy, and had filled the astronomical5 chair at Oxford6, proposed Mr. Newton as a Fellow of the Royal48 Society. The satisfaction which he derived7 from this circumstance appears to have been considerable; and in a letter to Mr. Oldenburg, of the 6th January, he says, “I am very sensible of the honour done me by the Bishop of Sarum in proposing me a candidate; and which, I hope, will be further conferred upon me by my election into the Society; and if so, I shall endeavour to testify my gratitude9, by communicating what my poor and solitary10 endeavours can effect towards the promoting your philosophical11 designs.” His election accordingly took place on the 11th January, the same day on which the Society agreed to transmit a description of his telescope to Mr. Huygens at Paris. The notice of his election, and the thanks of the Society for the communication of his telescope, were conveyed in the same letter, with an assurance that the Society “would take care that all right should be done him in the matter of this invention.” In his next letter to Oldenburg, written on the 18th January, 1671–2, he announces his optical discoveries in the following remarkable12 manner: “I desire that in your next letter you would inform me for what time the Society continue their weekly meetings; because if they continue them for any time, I am purposing them, to be considered of and examined, an account of a philosophical discovery which induced me to the making of the said telescope; and I doubt not but will prove much more grateful than the communication of that instrument; being in my judgment13 the oddest, if not the most considerable detection which hath hitherto been made in the operations of nature.”

This “considerable detection” was the discovery of the different refrangibility of the rays of light which we have already explained, and which led to the construction of his reflecting telescope. It was communicated to the Royal Society in a letter to Mr. Oldenburg, dated February 6th, and excited great interest among its members. The “solemn49 thanks” of the meeting were ordered to be transmitted to its author for his “very ingenious discourse14.” A desire was expressed to have it immediately printed, both for the purpose of having it well considered by philosophers, and for “securing the considerable notices thereof to the author against the arrogations of others;” and Dr. Seth Ward, Bishop of Salisbury, Mr. Boyle, and Dr. Hooke were desired to peruse15 and consider it, and to bring in a report upon it to the Society.

The kindness of this distinguished16 body, and the anxiety which they had already evinced for his reputation, excited on the part of Newton a corresponding feeling, and he gladly accepted of their proposal to publish his discourse in the monthly numbers in which the Transactions were then given to the world. “It was an esteem17,” says he,12 “of the Royal Society for most candid8 and able judges in philosophical matters, encouraged me to present them with that discourse of light and colours, which since they have so favourably18 accepted of, I do earnestly desire you to return them my cordial thanks. I before thought it a great favour to be made a member of that honourable19 body; but I am now more sensible of the advantages; for believe me, sir, I do not only esteem it a duty to concur20 with you in the promotion21 of real knowledge; but a great privilege, that, instead of exposing discourses22 to a prejudiced and common multitude, (by which means many truths have been baffled and lost), I may with freedom apply myself to so judicious23 and impartial24 an assembly. As to the printing of that letter, I am satisfied in their judgment, or else I should have thought it too straight and narrow for public view. I designed it only to those that know how to improve upon hints of things; and, therefore, to spare tediousness, omitted many such remarks and experiments50 as might be collected by considering the assigned laws of refractions; some of which I believe, with the generality of men, would yet be almost as taking as any I described. But yet, since the Royal Society have thought it fit to appear publicly, I leave it to their pleasure: and perhaps to supply the aforesaid defects, I may send you some more of the experiments to second it (if it be so thought fit), in the ensuing Transactions.”

Following the order which Newton himself adopted, we have, in the preceding chapter, given an account of the leading doctrine25 of the different refrangibility of light, and of the attempts to improve the reflecting telescope which that discovery suggested. We shall now, therefore, endeavour to make the reader acquainted with the other discoveries respecting colours which he at this time communicated to the Royal Society.

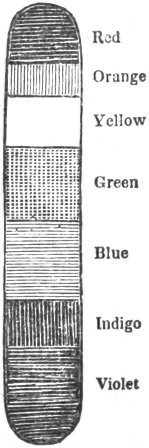

Having determined26, by experiments already described, that a beam of white light, as emitted from the sun, consisted of seven different colours, which possess different degrees of refrangibility, he measured the relative extent of the coloured spaces, and found them to have the proportions shown in fig27. 4, which represents the prismatic spectrum28, and which is nothing more than an elongated29 image of the sun produced by the rays being separated in different degrees from their original direction, the red being refracted least, and the violet most powerfully.

If we consider light as consisting of minute particles of matter, we may form some notion of its decomposition30 by the prism from the following popular illustration. If we take steel51 filings of seven different degrees of fineness and mix them together, there are two ways in which we may conceive the mass to be decomposed31, or, what is the same thing, all the seven different kinds of filings separated from each other. By means of seven sieves32 of different degrees of fineness, and so made that the finest will just transmit the finest powder and detain all the rest, while the next in fineness transmits the two finest powders and detains all the rest, and so on, it is obvious that all the powders may be completely separated from each other. If we again mix all the steel filings, and laying them upon a table, hold high above them a flat bar magnet, so that none of the filings are attracted, then if we bring the magnet nearer and nearer, we shall come to a point where the finest filings are drawn33 up to it. These being removed, and the magnet brought nearer still, the next finest powders will be attracted, and so on till we have thus drawn out of the mass all the powders in a separate state. We may conceive the bar magnet to be inclined to the surface of the steel filings, and so moved over the mass, that at the end nearest to them the heaviest or coarsest will be attracted, and all the remotest and the finest or lighter34 filings, while the rest are attracted to intermediate points, so that the seven different filings are not only separated, but are found adhering in separate patches to the surface of the flat magnet. The first of these methods, with the sieves, may represent the process of decomposing35 light, by which certain rays of white light are absorbed, or stifled36, or stopped in passing through bodies, while certain other rays are transmitted. The second method may represent the process of decomposing light by refraction, or by the attraction of certain rays farther from their original direction than other rays, and the different patches of filings upon the flat magnet may represent the spaces on the spectrum.

52 When a beam of white light is decomposed into the seven different colours of the spectrum, any particular colour, when once separated from the rest, is not susceptible37 of any change, or farther decomposition, whether it is refracted through prisms or reflected from mirrors. It may become fainter or brighter, but Newton never could, by any process, alter its colour or its refrangibility.

Among the various bodies which act upon light, it is conceivable that there might have been some which acted least upon the violet rays and most upon the red rays. Newton, however, found that this never took place; but that the same degree of refrangibility always belonged to the same colour, and the same colour to the same degree of refrangibility.

Having thus determined that the seven different colours of the spectrum were original or simple, he was led to the conclusion that whiteness or white light is a compound of all the seven colours of the spectrum, in the proportions in which they are represented in fig. 4. In order to prove this, or what is called the recomposition of white light out of the seven colours, he employed three different methods.

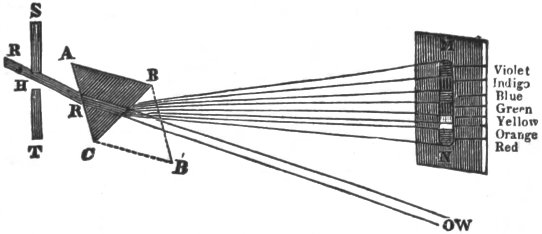

When the beam RR was separated into its elementary colours by the prism ABC, he received the53 colours on another prism BCB′, held either close to the first or a little behind it, and by the opposite refraction of this prism they were all refracted back into a beam of white light BW, which formed a white circular image on the wall at W, similar to what took place before any of the prisms were placed in its way.

The other method of recomposing white light consisted in making the spectrum fall upon a lens at some distance from it. When a sheet of white paper was held behind the lens, and removed to a proper distance, the colours were all refracted into a circular spot, and so blended as to reproduce light so perfectly38 white as not to differ sensibly from the direct light of the sun.

The last method of recomposing white light was one more suited to vulgar apprehension39. It consisted in attempting to compound a white by mixing the coloured powders used by painters. He was aware that such colours, from their very nature, could not compose a pure white; but even this imperfection in the experiment he removed by an ingenious device. He accordingly mixed one part of red lead, four parts of blue bice, and a proper proportion of orpiment and verdigris40. This mixture was dun, like wood newly cut, or like the human skin. He now took one-third of the mixture and rubbed it thickly on the floor of his room, where the sun shone upon it through the opened casement41, and beside it, in the shadow, he laid a piece of white paper of the same size. “Then going from them to the distance of twelve or eighteen feet, so that he could not discern the unevenness42 of the surface of the powder nor the little shadows let fall from the gritty particles thereof; the powder appeared intensely white, so as to transcend43 even the paper itself in whiteness.” By adjusting the relative illumination of the powders and the paper, he was able to make them both appear of the very same degree of54 whiteness. “For,” says he, “when I was trying this, a friend coming to visit me, I stopped him at the door, and before I told him what the colours were, or what I was doing, I asked him which of the two whites were the best, and wherein they differed! And after he had at that distance viewed them well, he answered, that they were both good whites, and that he could not say which was best, nor wherein their colours differed.” Hence Newton inferred that perfect whiteness may be compounded of different colours.

As all the various shades of colour which appear in the material world can be imitated by intercepting44 certain rays in the spectrum, and uniting all the rest, and as bodies always appear of the same colour as the light in which they are placed, he concluded, that the colours of natural bodies are not qualities inherent in the bodies themselves, but arise from the disposition45 of the particles of each body to stop or absorb certain rays, and thus to reflect more copiously46 the rays which are not thus absorbed.

No sooner were these discoveries given to the world than they were opposed with a degree of virulence47 and ignorance which have seldom been combined in scientific controversy48. Unfortunately for Newton, the Royal Society contained few individuals of pre-eminent49 talent capable of appreciating the truth of his discoveries, and of protecting him against the shafts50 of his envious51 and ignorant assailants. This eminent body, while they held his labours in the highest esteem, were still of opinion that his discoveries were fair subjects of discussion, and their secretary accordingly communicated to him all the papers which were written in opposition52 to his views. The first of these was by a Jesuit named Ignatius Pardies, Professor of Mathematics at Clermont, who pretended that the elongation of the sun’s image arose from the inequal incidence of the different rays on the first face of the prism, although55 Newton had demonstrated in his own discourse that this was not the case. In April, 1672, Newton transmitted to Oldenburg a decisive reply to the animadversions of Pardies; but, unwilling53 to be vanquished54, this disciple55 of Descartes took up a fresh position, and maintained that the elongation of the spectrum might be explained by the diffusion56 of light on the hypothesis of Grimaldi, or by the diffusion of undulations on the hypothesis of Hook. Newton again replied to these feeble reasonings; but he contented57 himself with reiterating58 his original experiments, and confirming them by more popular arguments, and the vanquished Jesuit wisely quitted the field.

Another combatant soon sprung up in the person of one Francis Linus, a physician in Liege,13 who, on the 6th October, 1674, addressed a letter to a friend in London, containing animadversions on Newton’s doctrine of colours. He boldly affirms, that in a perfectly clear sky the image of the sun made by a prism is never elongated, and that the spectrum observed by Newton was not formed by the true sunbeams, but by rays proceeding59 from some bright cloud. In support of these assertions, he appeals to frequently repeated experiments on the refractions and reflections of light which he had exhibited thirty years before to Sir Kenelm Digby, “who took notes upon them;” and he unblushingly states, that, if Newton had used the same industry as he did, he would never have “taken so impossible a task in hand, as to explain the difference between the length and breadth of the spectrum by the received laws of refraction.” When this letter was shown to Newton, he refused56 to answer it; but a letter was sent to Linus referring him to the answer to Pardies, and assuring him that the experiments on the spectrum were made when there was no bright cloud in the heavens. This reply, however, did not satisfy the Dutch experimentalist. On the 25th February, 1675, he addressed another letter to his friend, in which he gravely attempts to prove that the experiment of Newton was not made in a clear day;—that the prism was not close to the hole,—and that the length of the spectrum was not perpendicular60, or parallel to the length of the prism. Such assertions could not but irritate even the patient mind of Newton. He more than once declined the earnest request of Oldenburg to answer these observations; he stated, that, as the dispute referred to matters of fact, it could only be decided61 before competent witnesses, and he referred to the testimony62 of those who had seen his experiments. The entreaties63 of Oldenburg, however, prevailed over his own better judgment, and, “lest Mr. Linus should make the more stir,” this great man was compelled to draw up a long and explanatory reply to reasonings utterly64 contemptible65, and to assertions altogether unfounded. This answer, dated November 13th, 1675, could scarcely have been perused66 by Linus, who was dead on the 15th December, when his pupil Mr. Gascoigne, took up the gauntlet, and declared that Linus had shown to various persons in Liege the experiment which proved the spectrum to be circular, and that Sir Isaac could not be more confident on his side than they were on the other. He admitted, however, that the different results might arise from different ways of placing the prism. Pleased with the “handsome genius of Mr. Gascoigne’s letter,” Newton replied even to it, and suggested that the spectrum seen by Linus may have been the circular one, formed by one reflexion, or, what he thought more probable, the circular one formed by two refractions,57 and one intervening reflection from the base of the prism, which would be coloured if the prism was not an isosceles one. This suggestion seems to have enlightened the Dutch philosophers. Mr. Gascoigne, having no conveniences for making the experiments pointed67 out by Newton, requested Mr. Lucas of Liege to perform them in his own house. This ingenious individual, whose paper gave great satisfaction to Newton, and deserves the highest praise, confirmed the leading results of the English philosopher; but though the refracting angle of his prism was 60° and the refractions equal, he never could obtain a spectrum whose length was more than from three to three and a half times its breadth, while Newton found the length to be five times its breadth. In our author’s reply, he directs his attention principally to this point of difference. He repeated his measures with each of the three angles of three different prisms, and he affirmed that Mr. Lucas might make sure to find the image as long or longer than he had yet done, by taking a prism with plain surfaces, and with an angle of 66° or 67°. He admitted that the smallness of the angle in Mr. Lucas’s prism, viz. 60°, did not account for the shortness of the spectrum which he obtained with it; and he observed in one of his own prisms that the length of the image was greater in proportion to the refracting angle than it should have been; an effect which he ascribes to its having a greater refractive power. There is every reason to believe that the prism of Lucas had actually a less dispersive68 power than that of Newton; and had the Dutch philosopher measured its refractive power instead of guessing it, or had Newton been less confident than he was14 that all other prisms must give a58 spectrum of the same length as his in relation to its refracting angle and its index of refraction, the invention of the achromatic telescope would have been the necessary result. The objections of Lucas drove our author to experiments which he had never before made,—to measure accurately69 the lengths of the spectra70 with different prisms of different angles and different refractive powers; and had the Dutch philosopher maintained his position with more obstinacy71, he would have conferred a distinguished favour upon science, and would have rewarded Newton for all the vexation which had sprung from the minute discussion of his optical experiments.

Such was the termination of his disputes with the Dutch philosophers, and it can scarcely be doubted that it cost him more trouble to detect the origin of his adversaries72’ blunders, than to establish the great truths which they had attempted to overturn.

Harassing73 as such a controversy must have been to a philosopher like Newton, yet it did not touch those deep-seated feelings which characterize the noble and generous mind. No rival jealousy74 yet pointed the arguments of his opponents;—no charges of plagiarism75 were yet directed against his personal character. These aggravations of scientific controversy, however, he was destined76 to endure; and in the dispute which he was called to maintain both against Hooke and Huygens, the agreeable consciousness of grappling with men of kindred powers was painfully imbittered by the personality and jealousy with which it was conducted.

Dr. Robert Hooke was about seven years older than Newton, and was one of the ninety-eight original or unelected members of the Royal Society.59 He possessed77 great versatility78 of talent, yet, though his genius was of the most original cast, and his acquirements extensive, he had not devoted79 himself with fixed80 purpose to any particular branch of knowledge. His numerous and ingenious inventions, of which it is impossible to speak too highly, gave to his studies a practical turn which unfitted him for that continuous labour which physical researches so imperiously demand. The subjects of light, however, and of gravitation seem to have deeply occupied his thoughts before Newton appeared in the same field, and there can be no doubt that he had made considerable progress in both of these inquiries81. With a mind less divergent in its pursuits, and more endowed with patience of thought, he might have unveiled the mysteries in which both these subjects were enveloped82, and preoccupied83 the intellectual throne which was destined for his rival; but the infirm state of his health, the peevishness84 of temper which this occasioned, the number of unfinished inventions from which he looked both for fortune and fame, and, above all, his inordinate85 love of reputation, distracted and broke down the energies of his powerful intellect. In the more matured inquiries of his rivals he recognised, and often truly, his own incompleted speculations86; and when he saw others reaping the harvest for which he had prepared the ground, and of which he had sown the seeds, it was not easy to suppress the mortification87 which their success inspired. In the history of science, it has always been a difficult task to adjust the rival claims of competitors, when the one was allowed to have completed what the other was acknowledged to have begun. He who commences an inquiry88, and publishes his results, often goes much farther than he has announced to the world, and, pushing his speculations into the very heart of the subject, frequently submits them to the ear of friendship. From the pedestal of his published60 labours his rival begins his researches, and brings them to a successful issue; while he has in reality done nothing more than complete and demonstrate the imperfect speculations of his predecessor89. To the world, and to himself, he is no doubt in the position of the principal discoverer: but there is still some apology for his rival when he brings forward his unpublished labours; and some excuse for the exercise of personal feeling, when he measures the speed of his rival by his own proximity90 to the goal.

The conduct of Dr. Hooke would have been viewed with some such feeling, had not his arrogance91 on other occasions checked the natural current of our sympathy. When Newton presented his reflecting telescope to the Royal Society, Dr. Hooke not only criticised the instrument with undue92 severity, but announced that he possessed an infallible method of perfecting all kinds of optical instruments, so that “whatever almost hath been in notion and imagination, or desired in optics, may be performed with great facility and truth.”

Hooke had been strongly impressed with the belief, that light consisted in the undulations of a highly elastic93 medium pervading94 all bodies; and, guided by his experimental investigation95 of the phenomena96 of diffraction, he had even announced the great principle of interference, which has performed such an important part in modern science. Regarding himself, therefore, as in possession of the true theory of light, he examined the discoveries of Newton in their relation to his own speculative97 views, and, finding that their author was disposed to consider that element as consisting of material particles, he did not scruple98 to reject doctrines99 which he believed to be incompatible100 with truth. Dr. Hooke was too accurate an observer not to admit the general correctness of Newton’s observations. He allowed the existence of different refractions,61 the unchangeableness of the simple colours, and the production of white light by the union of all the colours of the spectrum; but he maintained that the different refractions arose from the splitting and rarefying of ethereal pulses, and that there are only two colours in nature, viz. red and violet, which produce by their mixture all the rest, and which are themselves formed by the two sides of a split pulse or undulation.

In reply to these observations, Newton wrote an able letter to Oldenburg, dated June 11, 1672, in which he examined with great boldness and force of argument the various objections of his opponent, and maintained the truth of his doctrine of colours, as independent of the two hypotheses respecting the origin and production of light. He acknowledged his own partiality to the doctrine of the materiality of light; he pointed out the defects of the undulatory theory; he brought forward new experiments in confirmation101 of his former results; and he refuted the opinions of Hooke respecting the existence of only two simple colours. No reply was made to the powerful arguments of Newton; and Hooke contented himself with laying before the Society his curious observations on the colours of soap-bubbles, and of plates of air, and in pursuing his experiments on the diffraction of light, which, after an interval102 of two years, he laid before the same body.

After he had thus silenced the most powerful of his adversaries, Newton was again called upon to defend himself against a new enemy. Christian103 Huygens, an eminent mathematician104 and natural philosopher, who, like Hooke, had maintained the undulatory theory of light, transmitted to Oldenburg various animadversions on the Newtonian doctrine; but though his knowledge of optics was of the most extensive kind, yet his objections were nearly as groundless as those of his less enlightened62 countryman. Attached to his own hypothesis respecting the nature of light, namely, to the system of undulation, he seems, like Dr. Hooke, to have regarded the discoveries of Newton as calculated to overturn it; but his principal objections related to the composition of colours, and particularly of white light, which he alleged105 could be obtained from the union of two colours, yellow and blue. To and similar objections, Newton replied that the colours in question were not simple yellows and blues106, but were compound colours, in which, together, all the colours of the spectrum were themselves blended; and though he evinced some strong traces of feeling at being again put upon his defence, yet his high respect for Huygens induced him to enter with patience on a fresh development of his doctrine. Huygens felt the reproof107 which the tone of this answer so gently conveyed, and in writing to Oldenburg, he used the expression, that Mr. Newton “maintained his doctrine with some concern.” To this our author replied, “As for Mr. Huygens’s expression, I confess it was a little ungrateful to me, to meet with objections which had been answered before, without having the least reason given me why those answers were insufficient108.” But though Huygens appears in this controversy as a rash objector to the Newtonian doctrine, it was afterward109 the fate of Newton to play a similar part against the Dutch philosopher. When Huygens published his beautiful law of double refraction in Iceland spar, founded on the finest experimental analysis of the phenomena, though presented as a result of the undulatory system, Newton not only rejected it, but substituted for it another law entirely110 inconsistent with the experiments of Huygens, which Newton himself had praised, and with those of all succeeding philosophers.

The influence of these controversies on the mind of Newton seems to have been highly exciting.63 Even the satisfaction of humbling111 all his antagonists112 he did not feel as a sufficient compensation for the disturbance113 of his tranquillity114. “I intend,” says he,15 “to be no farther solicitous115 about matters of philosophy. And therefore I hope you will not take it ill if you find me never doing any thing more in that kind; or rather that you will favour me in my determination, by preventing, so far as you can conveniently, any objections or other philosophical letters that may concern me.” In a subsequent letter in 1675, he says, “I had some thoughts of writing a further discourse about colours, to be read at one of your assemblies; but find it yet against the grain to put pen to paper any more on that subject;” and in a letter to Leibnitz, dated December the 9th, 1675, he observes, “I was so persecuted116 with discussions arising from the publication of my theory of light, that I blamed my own imprudence for parting with so substantial a blessing117 as my quiet to run after a shadow.”

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

controversies

|

|

| 争论 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

celebrated

|

|

| adj.有名的,声誉卓著的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

ward

|

|

| n.守卫,监护,病房,行政区,由监护人或法院保护的人(尤指儿童);vt.守护,躲开 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

bishop

|

|

| n.主教,(国际象棋)象 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

astronomical

|

|

| adj.天文学的,(数字)极大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

Oxford

|

|

| n.牛津(英国城市) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

derived

|

|

| vi.起源;由来;衍生;导出v.得到( derive的过去式和过去分词 );(从…中)得到获得;源于;(从…中)提取 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

candid

|

|

| adj.公正的,正直的;坦率的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

gratitude

|

|

| adj.感激,感谢 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

solitary

|

|

| adj.孤独的,独立的,荒凉的;n.隐士 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

philosophical

|

|

| adj.哲学家的,哲学上的,达观的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

judgment

|

|

| n.审判;判断力,识别力,看法,意见 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

discourse

|

|

| n.论文,演说;谈话;话语;vi.讲述,著述 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

peruse

|

|

| v.细读,精读 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

distinguished

|

|

| adj.卓越的,杰出的,著名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

esteem

|

|

| n.尊敬,尊重;vt.尊重,敬重;把…看作 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

favourably

|

|

| adv. 善意地,赞成地 =favorably | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

honourable

|

|

| adj.可敬的;荣誉的,光荣的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

concur

|

|

| v.同意,意见一致,互助,同时发生 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

promotion

|

|

| n.提升,晋级;促销,宣传 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

discourses

|

|

| 论文( discourse的名词复数 ); 演说; 讲道; 话语 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

judicious

|

|

| adj.明智的,明断的,能作出明智决定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

impartial

|

|

| adj.(in,to)公正的,无偏见的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

doctrine

|

|

| n.教义;主义;学说 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

determined

|

|

| adj.坚定的;有决心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

spectrum

|

|

| n.谱,光谱,频谱;范围,幅度,系列 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

elongated

|

|

| v.延长,加长( elongate的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

decomposition

|

|

| n. 分解, 腐烂, 崩溃 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

decomposed

|

|

| 已分解的,已腐烂的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

sieves

|

|

| 筛,漏勺( sieve的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

drawn

|

|

| v.拖,拉,拔出;adj.憔悴的,紧张的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

lighter

|

|

| n.打火机,点火器;驳船;v.用驳船运送;light的比较级 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

decomposing

|

|

| 腐烂( decompose的现在分词 ); (使)分解; 分解(某物质、光线等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

stifled

|

|

| (使)窒息, (使)窒闷( stifle的过去式和过去分词 ); 镇压,遏制; 堵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

susceptible

|

|

| adj.过敏的,敏感的;易动感情的,易受感动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

perfectly

|

|

| adv.完美地,无可非议地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

apprehension

|

|

| n.理解,领悟;逮捕,拘捕;忧虑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

verdigris

|

|

| n.铜锈;铜绿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

casement

|

|

| n.竖铰链窗;窗扉 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

unevenness

|

|

| n. 不平坦,不平衡,不匀性 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

transcend

|

|

| vt.超出,超越(理性等)的范围 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

intercepting

|

|

| 截取(技术),截接 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

disposition

|

|

| n.性情,性格;意向,倾向;排列,部署 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

copiously

|

|

| adv.丰富地,充裕地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

virulence

|

|

| n.毒力,毒性;病毒性;致病力 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

controversy

|

|

| n.争论,辩论,争吵 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

eminent

|

|

| adj.显赫的,杰出的,有名的,优良的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

shafts

|

|

| n.轴( shaft的名词复数 );(箭、高尔夫球棒等的)杆;通风井;一阵(疼痛、害怕等) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

envious

|

|

| adj.嫉妒的,羡慕的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

opposition

|

|

| n.反对,敌对 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

unwilling

|

|

| adj.不情愿的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

vanquished

|

|

| v.征服( vanquish的过去式和过去分词 );战胜;克服;抑制 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

disciple

|

|

| n.信徒,门徒,追随者 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

diffusion

|

|

| n.流布;普及;散漫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

contented

|

|

| adj.满意的,安心的,知足的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

reiterating

|

|

| 反复地说,重申( reiterate的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

proceeding

|

|

| n.行动,进行,(pl.)会议录,学报 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

perpendicular

|

|

| adj.垂直的,直立的;n.垂直线,垂直的位置 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

decided

|

|

| adj.决定了的,坚决的;明显的,明确的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

testimony

|

|

| n.证词;见证,证明 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

entreaties

|

|

| n.恳求,乞求( entreaty的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

utterly

|

|

| adv.完全地,绝对地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

contemptible

|

|

| adj.可鄙的,可轻视的,卑劣的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

perused

|

|

| v.读(某篇文字)( peruse的过去式和过去分词 );(尤指)细阅;审阅;匆匆读或心不在焉地浏览(某篇文字) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

pointed

|

|

| adj.尖的,直截了当的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

Dispersive

|

|

| adj. 分散的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

accurately

|

|

| adv.准确地,精确地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

spectra

|

|

| n.光谱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

obstinacy

|

|

| n.顽固;(病痛等)难治 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

adversaries

|

|

| n.对手,敌手( adversary的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

harassing

|

|

| v.侵扰,骚扰( harass的现在分词 );不断攻击(敌人) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

jealousy

|

|

| n.妒忌,嫉妒,猜忌 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

plagiarism

|

|

| n.剽窃,抄袭 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

destined

|

|

| adj.命中注定的;(for)以…为目的地的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

possessed

|

|

| adj.疯狂的;拥有的,占有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

versatility

|

|

| n.多才多艺,多样性,多功能 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

devoted

|

|

| adj.忠诚的,忠实的,热心的,献身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

fixed

|

|

| adj.固定的,不变的,准备好的;(计算机)固定的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

inquiries

|

|

| n.调查( inquiry的名词复数 );疑问;探究;打听 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

enveloped

|

|

| v.包围,笼罩,包住( envelop的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

preoccupied

|

|

| adj.全神贯注的,入神的;被抢先占有的;心事重重的v.占据(某人)思想,使对…全神贯注,使专心于( preoccupy的过去式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

peevishness

|

|

| 脾气不好;爱发牢骚 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

inordinate

|

|

| adj.无节制的;过度的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

speculations

|

|

| n.投机买卖( speculation的名词复数 );思考;投机活动;推断 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

mortification

|

|

| n.耻辱,屈辱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

inquiry

|

|

| n.打听,询问,调查,查问 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

predecessor

|

|

| n.前辈,前任 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

proximity

|

|

| n.接近,邻近 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

arrogance

|

|

| n.傲慢,自大 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

undue

|

|

| adj.过分的;不适当的;未到期的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

elastic

|

|

| n.橡皮圈,松紧带;adj.有弹性的;灵活的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

pervading

|

|

| v.遍及,弥漫( pervade的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

investigation

|

|

| n.调查,调查研究 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

phenomena

|

|

| n.现象 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

speculative

|

|

| adj.思索性的,暝想性的,推理的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

scruple

|

|

| n./v.顾忌,迟疑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

99

doctrines

|

|

| n.教条( doctrine的名词复数 );教义;学说;(政府政策的)正式声明 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

100

incompatible

|

|

| adj.不相容的,不协调的,不相配的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

101

confirmation

|

|

| n.证实,确认,批准 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

102

interval

|

|

| n.间隔,间距;幕间休息,中场休息 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

103

Christian

|

|

| adj.基督教徒的;n.基督教徒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

104

mathematician

|

|

| n.数学家 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

105

alleged

|

|

| a.被指控的,嫌疑的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

106

blues

|

|

| n.抑郁,沮丧;布鲁斯音乐 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

107

reproof

|

|

| n.斥责,责备 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

108

insufficient

|

|

| adj.(for,of)不足的,不够的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

109

afterward

|

|

| adv.后来;以后 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

110

entirely

|

|

| ad.全部地,完整地;完全地,彻底地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

111

humbling

|

|

| adj.令人羞辱的v.使谦恭( humble的现在分词 );轻松打败(尤指强大的对手);低声下气 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

112

antagonists

|

|

| 对立[对抗] 者,对手,敌手( antagonist的名词复数 ); 对抗肌; 对抗药 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

113

disturbance

|

|

| n.动乱,骚动;打扰,干扰;(身心)失调 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

114

tranquillity

|

|

| n. 平静, 安静 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

115

solicitous

|

|

| adj.热切的,挂念的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

116

persecuted

|

|

| (尤指宗教或政治信仰的)迫害(~sb. for sth.)( persecute的过去式和过去分词 ); 烦扰,困扰或骚扰某人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

117

blessing

|

|

| n.祈神赐福;祷告;祝福,祝愿 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |