The appointment of Newton to the Lucasian chair at Cambridge seems to have been coeval1 with his grandest discoveries. The first of these of which the date is well authenticated2 is that of the different refrangibility of the rays of light, which he established in 1666. The germ of the doctrine3 of universal gravitation seems to have presented itself to him in the same year, or at least in 1667; and “in the year 1666 or before”9 he was in possession of his method of fluxions, and he had brought it to such a state in the beginning of 1669, that he permitted Dr. Barrow to communicate it to Mr. Collins on the 20th of June in that year.

Although we have already mentioned, on the authority of a written memorandum4 of Newton himself, that he purchased a prism at Cambridge in 1664, yet he does not appear to have made any use of it, as he informs us that it was in 1666 that he “procured31 a triangular6 glass prism to try therewith the celebrated7 phenomena8 of colours.”10 During that year he had applied9 himself to the grinding of “optic glasses, of other figures than spherical11,” and having, no doubt, experienced the impracticability of executing such lenses, the idea of examining the phenomena of colour was one of those sagacious and fortunate impulses which more than once led him to discovery. Descartes in his Dioptrice, published in 1629, and more recently James Gregory in his Optica Promota published in 1663, had shown that parallel and diverging12 rays could be reflected or refracted, with mathematical accuracy, to a point or focus, by giving the surface a parabolic, an elliptical, or a hyperbolic form, or some other form not spherical. Descartes had even invented and described machines by which lenses of these shapes could be ground and polished, and the perfection of the refracting telescope was supposed to depend on the degree of accuracy with which they could be executed.

In attempting to grind glasses that were not spherical, Newton seems to have conjectured13 that the defects of lenses, and consequently of refracting telescopes, might arise from some other cause than the imperfect convergency of rays to a single point, and this conjecture14 was happily realized in those fine discoveries of which we shall now endeavour to give some account.

When Newton began this inquiry16, philosophers of the highest genius were directing all the energies of their mind to the subject of light, and to the improvement of the refracting telescope. James Gregory of Aberdeen had invented his reflecting telescope. Descartes had explained the theory and exerted himself in perfecting the construction of the common refracting telescope, and Huygens had not32 only executed the magnificent instruments by which he discovered the ring and the satellites of Saturn17, but had begun those splendid researches respecting the nature of light, and the phenomena of double refraction, which have led his successors to such brilliant discoveries. Newton, therefore, arose when the science of light was ready for some great accession, and at the precise time when he was required to propagate the impulse which it had received from his illustrious predecessors18.

The ignorance which then prevailed respecting the nature and origin of colours is sufficiently20 apparent from the account we have already given of Dr. Barrow’s speculations21 on this subject. It was always supposed that light of every colour was equally refracted or bent22 out of its direction when it passed through any lens or prism, or other refracting medium; and though the exhibition of colours by the prism had been often made previous to the time of Newton, yet no philosopher seems to have attempted to analyze23 the phenomena.

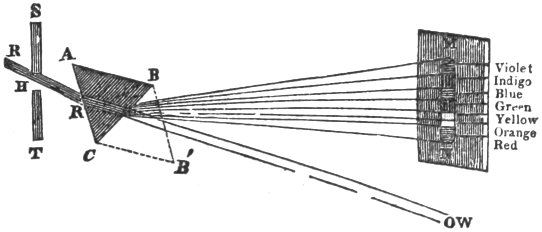

When he had procured5 his triangular glass prism, a section of which is shown at ABC, (fig10. 1,) he made a hole H in one of his window-shutters, SHT, and having darkened his chamber24, he let in a convenient quantity of the sun’s light RR, which, passing33 through the prism ABC, was so refracted as to exhibit all the different colours on the wall at MN, forming an image about five times as long as it was broad. “It was at first,” says our author, “a very pleasing divertisement to view the vivid and intense colours produced thereby,” but this pleasure was immediately succeeded by surprise at various circumstances which he had not expected. According to the received laws of refraction, he expected the image MN to be circular, like the white image at W, which the sunbeam RR had formed on the wall previous to the interposition of the prism; but when he found it to be no less than five times larger than its breadth, it “excited in him a more than ordinary curiosity to examine from whence it might proceed. He could scarcely think that the various thickness of the glass, or the termination with shadow or darkness, could have any influence on light to produce such an effect: yet he thought it not amiss first to examine those circumstances, and so find what would happen by transmitting light through parts of the glass of divers25 thicknesses, or through holes in the window of divers bignesses, or by setting the prism without (on the other side of ST), so that the light might pass through it and be refracted before it was terminated by the hole; but he found none of these circumstances material. The fashion of the colours was in all those cases the same.”

Newton next suspected that some unevenness26 in the glass, or other accidental irregularity, might cause the dilatation of the colours. In order to try this, he took another prism BCB′, and placed it in such a manner that the light RRW passing through them both might be refracted contrary ways, and thus returned by BCB′ into that course RRW, from which the prism ABC had diverted it, for by this means he thought the regular effects of the prism ABC would be destroyed by the prism BCB′, and the irregular ones more augmented28 by the multiplicity34 of refractions. The result was, that the light which was diffused29 by the first prism ABC into an oblong form, was reduced by the second prism BCB′ into a circular one W, with as much regularity27 as when it did not pass through them at all; so that whatever was the cause of the length of the image MN, it did not arise from any irregularity in the prism.

Our author next proceeded to examine more critically what might be effected by the difference of the incidence of the rays proceeding30 from different parts of the sun’s disk: but by taking accurate measures of the lines and angles, he found that the angle of the emergent rays should be 31 minutes equal to the sun’s diameter, whereas the real angle subtended by MN at the hole H was 2° 49′. But as this computation was founded on the hypothesis, that the sine of the angle of incidence was proportional to the sine of the angle of refraction, which from his own experience he could not imagine to be so erroneous as to make that angle but 31′, which was in reality 2° 49′, yet “his curiosity caused him again to take up his prism” ABC, and having turned it round in both directions, so as to make the rays RR fall both with greater and with less obliquity31 upon the face AC, he found that the colours on the wall did not sensibly change their place; and hence he obtained a decided32 proof that they could not be occasioned by a difference in the incidence of the light radiating from different parts of the sun’s disk.

Newton then began to suspect that the rays, after passing through the prism, might move in curve lines, and, in proportion to the different degrees of curvature, might tend to different parts of the wall; and this suspicion was strengthened by the recollection that he had often seen a tennis-ball struck with an oblique33 racket describe such a curve line. In this case a circular and a progressive motion is communicated to the ball by the stroke, and in consequence of this, the direction of its motion was curvilineal,35 so that if the rays of light were globular bodies, they might acquire a circulating motion by their oblique passage out of one medium into another, and thus move like the tennis-ball in a curve line. Notwithstanding, however, “this plausible34 ground of suspicion,” he could discover no such curvature in their direction, and, what was enough for his purpose, he observed that the difference between the length MN of the image, and the diameter of the hole H, was proportional to their distance HM, which could not have happened had the rays moved in curvilineal paths.

These different hypotheses, or suspicions, as Newton calls them, being thus gradually removed, he was at length led to an experiment which determined35 beyond a doubt the true cause of the elongation of the coloured image. Having taken a board with a small hole in it, he placed it behind the face BC of the prism, and close to it, so that he could transmit through the hole any one of the colours in MN, and keep back all the rest. When the hole, for example, was near C, no other light but the red fell upon the wall at N. He then placed behind N another board with a hole in it, and behind this board he placed another prism, so as to receive the red light at N, which passed through this hole in the second board. He then turned round the first prism ABC so as to make all the colours pass in succession through these two holes, and he marked their places on the wall. From the variation of these places, he saw that the red rays at N were less refracted by the second prism than the orange rays, the orange less than the yellow, and so on, the violet being more refracted than all the rest.

Hence he drew the grand conclusion, that light was not homogeneous, but consisted of rays, some of which were more refrangible than others.

As soon as this important truth was established, Sir Isaac saw that a lens which refracts light exactly36 like a prism must also refract the differently coloured rays with different degrees of force, bringing the violet rays to a focus nearer the glass than the red rays. This is shown in fig. 2, where LL is a convex lens, and S, L, SL rays of the sun falling upon it in parallel directions. The violet rays existing in the white light SL being more refrangible than the rest, will be more refracted or bent, and will meet at V, forming there a violet image of the sun. In like manner the yellow rays will form an image of the sun at Y, and so on, the red rays, which are the least refrangible, being brought to a focus at R, and there forming a red image of the sun.

Hence, if we suppose LL to be the object-glass of a telescope directed to the sun, and MM an eye-glass through which the eye at E sees magnified the image or picture of the sun formed by LL, it cannot see distinctly all the different images between R and V. If it is adjusted so as to see distinctly the yellow image at Y, as it is in the figure, it will not see distinctly either the red or violet images, nor indeed any of them but the yellow one. There will consequently be a distinct yellow image, with indistinct images of all the other colours, producing great confusion and indistinctness of vision. As soon as Sir Isaac perceived this result of his discovery, he abandoned his attempts to improve the refracting telescope,37 and took into consideration the principle of reflection; and as he found that rays of all colours were reflected regularly, so that the angle of reflection was equal to the angle of incidence, he concluded that, upon this principle, optical instruments might be brought to any degree of perfection imaginable, provided a reflecting substance could be found which could polish as finely as glass, and reflect as much light as glass transmits, and provided a method of communicating to it a parabolic figure could be obtained. These difficulties, however, appeared to him very great, and he even thought them insuperable when he considered that, as any irregularity in a reflecting surface makes the rays deviate36 five or six times more from their true path than similar irregularities in a refracting surface, a much greater degree of nicety would be required in figuring reflecting specula than refracting lenses.

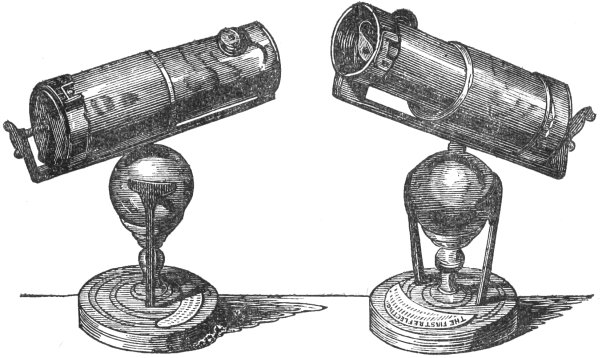

Such was the progress of Newton’s optical discoveries, when he was forced to quit Cambridge in 1666 by the plague which then desolated37 England, and more than two years elapsed before he proceeded any farther. In 1668 he resumed the inquiry, and having thought of a delicate method of polishing, proper for metals, by which, as he conceived, “the figure would be corrected to the last,” he began to put this method to the test of experiment. At this time he was acquainted with the proposal of Mr. James Gregory, contained in his Optica Promota, to construct a reflecting telescope with two concave specula, the largest of which had a hole in the middle of the larger speculum, to transmit the light to an eye-glass;11 but he conceived that it would be38 an improvement on this instrument to place the eye-glass at the side of the tube, and to reflect the rays to it by an oval plane speculum. One of these instruments he actually executed with his own hands; and he gave an account of it in a letter to a friend, dated February 23d, 1668–9, a letter which is also remarkable38 for containing the first allusion39 to his discoveries respecting colours. Previous to this he was in correspondence on the subject with Mr. Ent, afterward40 Sir George Ent, one of the original council of the Royal Society, an eminent41 medical writer of his day, and President of the College of Physicians. In a letter to Mr. Ent he had promised an account of his telescope to their mutual42 friend, and the letter to which we now allude43 contained the fulfilment of that promise. The telescope was six inches long. It bore an aperture44 in the large speculum something more than an inch, and as the eye-glass was a plano-convex lens, whose focal length was one-sixth or one-seventh of an inch, it magnified about forty times, which, as Newton remarks, was more than any six-foot tube (meaning refracting telescopes) could do with distinctness. On account of the badness of the materials, however, and the want of a good polish, it represented objects less distinct than a six-feet tube, though he still thought it would be equal to a three or four feet tube directed to common objects. He had seen through it Jupiter distinctly with his four satellites, and also the horns or moon-like phases of Venus, though this last phenomenon required some niceness in adjusting the instrument.

Although Newton considered this little instrument39 as in itself contemptible45, yet he regarded it as an “epitome of what might be done;” and he expressed his conviction that a six-feet telescope might be made after this method, which would perform as well as a sixty or a hundred feet telescope made in the common way; and that if a common refracting telescope could be made of the “purest glass exquisitely46 polished, with the best figure that any geometrician (Descartes, &c.) hath or can design,” it would scarcely perform better than a common telescope. This, he adds, may seem a paradoxical assertion, yet he continues, “it is the necessary consequence of some experiments which I have made concerning the nature of light.”

The telescope now described possesses a very peculiar47 interest, as being the first reflecting one which was ever executed and directed to the heavens. James Gregory, indeed, had attempted, in 1664 or 1665, to construct his instrument. He employed Messrs. Rives and Cox, who were celebrated glass-grinders of that time, to execute a concave speculum of six feet radius48, and likewise a small one; but as they had failed in polishing the large one, and as Mr. Gregory was on the eve of going abroad, he troubled himself no farther about the experiment, and the tube of the telescope was never made. Some time afterward, indeed, he “made some trials both with a little concave and convex speculum,” but, “possessed with the fancy of the defective49 figure, he would not be at the pains to fix every thing in its due distance.”

Such were the earliest attempts to construct the reflecting telescope, that noble instrument which has since effected such splendid discoveries in astronomy. Looking back from the present advanced state of practical science, how great is the contrast between the loose specula of Gregory and the fine Gregorian telescopes of Hadley, Short, and Veitch,—between the humble50 six-inch tube of Newton and the gigantic instruments of Herschel and Ramage.

40 The success of this first experiment inspired Newton with fresh zeal51, and though his mind was now occupied with his optical discoveries, with the elements of his method of fluxions, and with the expanding germ of his theory of universal gravitation, yet with all the ardour of youth he applied himself to the laborious52 operation of executing another reflecting telescope with his own hands. This instrument, which was better than the first, though it lay by him several years, excited some interest at Cambridge; and Sir Isaac himself informs us, that one of the fellows of Trinity College had completed a telescope of the same kind, which he considered as somewhat superior to his own. The existence of these telescopes having become known to the Royal Society, Newton was requested to send his instrument for examination to that learned body. He accordingly transmitted it to Mr. Oldenburg in December, 1671, and from this epoch53 his name began to acquire that celebrity54 by which it has been so peculiarly distinguished55.

On the 11th of January, 1672, it was announced to the Royal Society that his reflecting telescope had been shown to the king, and had been examined by the president, Sir Robert Moray, Sir Paul Neale, Sir Christopher Wren56, and Mr. Hook. These gentlemen entertained so high an opinion of it, that, in order to secure the honour of the contrivance to its author, they advised the inventor to send a drawing and description of it to Mr. Huygens at Paris. Mr. Oldenburg accordingly drew up a description of it in Latin, which, after being corrected by Mr. Newton, was transmitted to that eminent philosopher. This telescope, of which the annexed57 is an accurate drawing, is carefully preserved in the library of the Royal Society of London, with the following inscription:—

“Invented by Sir Isaac Newton and made with his own hands, 1671.”

Sir Isaac Newton’s Reflecting Telescope.

42 It does not appear that Newton executed any other reflecting telescopes than the two we have mentioned. He informs us that he repolished and greatly improved a fourteen-feet object-glass, executed by a London artist, and having proposed in 1678 to substitute glass reflectors in place of metallic58 specula, he tried to make a reflecting telescope on this principle four feet long, and with a magnifying power of 150. The glass was wrought59 by a London artist, and though it seemed well finished, yet, when it was quicksilvered on its convex side, it exhibited all over the glass innumerable inequalities, which gave an indistinctness to every object. He expresses, however, his conviction that nothing but good workmanship is wanting to perfect these telescopes, and he recommends their consideration “to the curious in figuring glasses.”

For a period of fifty years this recommendation excited no notice. At last Mr. James Short of Edinburgh, an artist of consummate60 skill, executed about the year 1730 no fewer than six reflecting telescopes with glass specula, three of fifteen inches, and three of nine inches in focal length. He found it extremely troublesome to give them a true figure with parallel surfaces; and several of them when finished turned out useless, in consequence of the veins61 which then appeared in the glass. Although these instruments performed remarkably62 well, yet the light was fainter than he expected, and from this cause, combined with the difficulty of finishing them, he afterward devoted63 his labours solely64 to those with metallic specula.

At a later period, in 1822, Mr. G. B. Airy of Trinity College, and one of the distinguished successors of Newton in the Lucasian chair, resumed the consideration of glass specula, and demonstrated that the aberration65 both of figure and of colour might be corrected in these instruments. Upon this ingenious principle Mr. Airy executed more than43 one telescope, but though the result of the experiment was such as to excite hopes of ultimate success, yet the construction of such instruments is still a desideratum in practical science.

Such were the attempts which Sir Isaac Newton made to construct reflecting telescopes; but notwithstanding the success of his labours, neither the philosopher nor the practical optician seems to have had courage to pursue them. A London artist, indeed, undertook to imitate these instruments; but Sir Isaac informs us, that “he fell much short of what he had attained66, as he afterward understood by discoursing67 with the under workmen he had employed.” After a long period of fifty years, John Hadley, Esq. of Essex, a Fellow of the Royal Society, began in 1719 or 1720 to execute a reflecting telescope. His scientific knowledge and his manual dexterity68 fitted him admirably for such a task, and, probably after many failures, he constructed two large telescopes about five feet three inches long, one of which, with a speculum six inches in diameter, was presented to the Royal Society in 1723. The celebrated Dr. Bradley and the Rev19. Mr. Pound compared it with the great Huygenian refractor 123 feet long. It bore as high a magnifying power as the Huygenian telescope: it showed objects equally distinct, though not altogether so clear and bright, and it exhibited every celestial69 object that had been discovered by Huygens,—the five satellites of Saturn, the shadow of Jupiter’s satellites on his disk, the black list in Saturn’s ring, and the edge of his shadow cast on the ring. Encouraged and instructed by Mr. Hadley, Dr. Bradley began the construction of reflecting telescopes, and succeeded so well that he would have completed one of them, had he not been obliged to change his residence. Some time afterward he and the Honourable70 Samuel Molyneux undertook the task together at Kew, and attempted to execute specula about twenty-six inches in focal44 length; but notwithstanding Dr. Bradley’s former experience, and Mr. Hadley’s frequent instructions, it was a long time before they succeeded. The first good instrument which they finished was in May, 1724. It was twenty-six inches in focal length; but they afterward completed a very large one of eight feet, the largest that had ever been made. The first of these instruments was afterward elegantly fitted up by Mr. Molyneux, and presented to his majesty71 John V. King of Portugal.

The great object of these two able astronomers72 was to reduce the method of making specula to such a degree of certainty that they could be manufactured for public sale. Mr. Hauksbee had indeed made a good one about three and a half feet long, and had proceeded to the execution of two others, one of six feet, and another of twelve feet in focal length; but Mr. Scarlet73 and Mr. Hearne, having received all the information which Mr. Molyneux had acquired, constructed them for public sale; and the reflecting telescope has ever since been an article of trade with every regular optician.

As Sir Isaac Newton was at this time President of the Royal Society, he had the high satisfaction of seeing his own invention become an instrument of public use, and of great advantage to science, and he no doubt felt the full influence of this triumph of his skill. Still, however, the reflecting telescope had not achieved any new discovery in the heavens. The latest accession to astronomy had been made by the ordinary refractors of Huygens, labouring under all the imperfections of coloured light; and this long pause in astronomical74 discovery seemed to indicate that man had carried to its farthest limits his power of penetrating75 into the depths of the universe. This, however, was only one of those stationary76 positions from which human genius takes a new and a loftier elevation77. While the English opticians were thus practising the recent art of grinding45 specula, Mr. James Short of Edinburgh was devoting to the subject all the energies of his youthful mind. In 1732, and in the 22d year of his age, he began his labours, and he carried to such high perfection the art of grinding and polishing specula, and of giving them the true parabolic figure, that, with a telescope fifteen inches in focal length, he read in the Philosophical78 Transactions at the distance of 500 feet, and frequently saw the five satellites of Saturn together,—a power which was beyond the reach even of Hadley’s six-feet instrument. The celebrated Maclaurin compared the telescopes of Short with those made by the best London artists, and so great was their superiority, that his small telescopes were invariably superior to larger ones from London. In 1742, after he had settled as an optician in the metropolis79, he executed for Lord Thomas Spencer a reflecting telescope, twelve feet in focal length, for 630l.; in 1752 he completed one for the King of Spain, at the expense of 1200l.; and a short time before his death, which took place in 1768, he finished the specula of the large telescope which was mounted equatorially for the observatory80 of Edinburgh by his brother Thomas Short, who was offered twelve hundred guineas for it by the King of Denmark.

Although the superiority of these instruments, which were all of the Gregorian form, demonstrated the value of the reflecting telescope, yet no skilful81 hand had yet directed it to the heavens; and it was reserved for Dr. Herschel to employ it as an instrument of discovery, to exhibit to the eye of man new worlds and new systems, and to bring within the grasp of his reason those remote regions of space to which his imagination even had scarcely ventured to extend its power. So early as 1774 he completed a five-feet Newtonian reflector, and he afterward executed no fewer than two hundred 7 feet, one hundred and fifty 10 feet, and eighty 20 feet specula. In46 1781 he began a reflector thirty feet long, and having a speculum thirty-six inches in diameter; and under the munificent82 patronage83 of George III. he completed, in 1789, his gigantic instrument forty feet long, with a speculum forty-nine and a half inches in diameter. The genius and perseverance84 which created instruments of such transcendent magnitude were not likely to terminate with their construction. In the examination of the starry85 heavens, the ultimate object of his labours, Dr. Herschel exhibited the same exalted86 qualifications, and in a few years he rose from the level of humble life to the enjoyment87 of a name more glorious than that of the sages88 and warriors89 of ancient times, and as immortal90 as the objects with which it will be for ever associated. Nor was it in the ardour of the spring of life that these triumphs of reason were achieved. Dr. Herschel had reached the middle of his course before his career of discovery began, and it was in the autumn and winter of his days that he reaped the full harvest of his glory. The discovery of a new planet at the verge15 of the solar system was the first trophy91 of his skill, and new double and multiple stars, and new nebul?, and groups of celestial bodies were added in thousands to the system of the universe. The spring-tide of knowledge which was thus let in upon the human mind continued for a while to spread its waves over Europe; but when it sank to its ebb92 in England, there was no other bark left upon the strand93 but that of the Deucalion of Science, whose home had been so long upon its waters.

During the life of Dr. Herschel, and during the reign94, and within the dominions95 of his royal patron, four new planets were added to the solar system, but they were detected by telescopes of ordinary power; and we venture to state, that since the reign of George III. no attempt has been made to keep up the continuity of Dr. Herschel’s discoveries.

Mr. Herschel, his distinguished son, has indeed47 completed more than one telescope of considerable size; Mr. Ramage, of Aberdeen, has executed reflectors rivalling almost those of Slough;—and Lord Oxmantown, an Irish nobleman of high promise, is now engaged on an instrument of great size. But what avail the enthusiasm and the efforts of individual minds in the intellectual rivalry96 of nations? When the proud science of England pines in obscurity, blighted97 by the absence of the royal favour, and of the nation’s sympathy;—when its chivalry98 fall unwept and unhonoured;—how can it sustain the conflict against the honoured and marshalled genius of foreign lands?

点击 收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

coeval

|

|

| adj.同时代的;n.同时代的人或事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

authenticated

|

|

| v.证明是真实的、可靠的或有效的( authenticate的过去式和过去分词 );鉴定,使生效 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

doctrine

|

|

| n.教义;主义;学说 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

memorandum

|

|

| n.备忘录,便笺 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

procured

|

|

| v.(努力)取得, (设法)获得( procure的过去式和过去分词 );拉皮条 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

triangular

|

|

| adj.三角(形)的,三者间的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

celebrated

|

|

| adj.有名的,声誉卓著的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

phenomena

|

|

| n.现象 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

applied

|

|

| adj.应用的;v.应用,适用 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

fig

|

|

| n.无花果(树) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

spherical

|

|

| adj.球形的;球面的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

diverging

|

|

| 分开( diverge的现在分词 ); 偏离; 分歧; 分道扬镳 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

conjectured

|

|

| 推测,猜测,猜想( conjecture的过去式和过去分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

conjecture

|

|

| n./v.推测,猜测 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

verge

|

|

| n.边,边缘;v.接近,濒临 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

inquiry

|

|

| n.打听,询问,调查,查问 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

Saturn

|

|

| n.农神,土星 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

predecessors

|

|

| n.前任( predecessor的名词复数 );前辈;(被取代的)原有事物;前身 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

rev

|

|

| v.发动机旋转,加快速度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

sufficiently

|

|

| adv.足够地,充分地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

speculations

|

|

| n.投机买卖( speculation的名词复数 );思考;投机活动;推断 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

bent

|

|

| n.爱好,癖好;adj.弯的;决心的,一心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

analyze

|

|

| vt.分析,解析 (=analyse) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

24

chamber

|

|

| n.房间,寝室;会议厅;议院;会所 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

25

divers

|

|

| adj.不同的;种种的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

26

unevenness

|

|

| n. 不平坦,不平衡,不匀性 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

27

regularity

|

|

| n.规律性,规则性;匀称,整齐 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

28

Augmented

|

|

| adj.增音的 动词augment的过去式和过去分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

29

diffused

|

|

| 散布的,普及的,扩散的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

30

proceeding

|

|

| n.行动,进行,(pl.)会议录,学报 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

31

obliquity

|

|

| n.倾斜度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

32

decided

|

|

| adj.决定了的,坚决的;明显的,明确的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

33

oblique

|

|

| adj.斜的,倾斜的,无诚意的,不坦率的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

34

plausible

|

|

| adj.似真实的,似乎有理的,似乎可信的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

35

determined

|

|

| adj.坚定的;有决心的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

36

deviate

|

|

| v.(from)背离,偏离 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

37

desolated

|

|

| adj.荒凉的,荒废的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

38

remarkable

|

|

| adj.显著的,异常的,非凡的,值得注意的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

39

allusion

|

|

| n.暗示,间接提示 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

40

afterward

|

|

| adv.后来;以后 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

41

eminent

|

|

| adj.显赫的,杰出的,有名的,优良的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

42

mutual

|

|

| adj.相互的,彼此的;共同的,共有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

43

allude

|

|

| v.提及,暗指 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

44

aperture

|

|

| n.孔,隙,窄的缺口 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

45

contemptible

|

|

| adj.可鄙的,可轻视的,卑劣的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

46

exquisitely

|

|

| adv.精致地;强烈地;剧烈地;异常地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

47

peculiar

|

|

| adj.古怪的,异常的;特殊的,特有的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

48

radius

|

|

| n.半径,半径范围;有效航程,范围,界限 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

49

defective

|

|

| adj.有毛病的,有问题的,有瑕疵的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

50

humble

|

|

| adj.谦卑的,恭顺的;地位低下的;v.降低,贬低 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

51

zeal

|

|

| n.热心,热情,热忱 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

52

laborious

|

|

| adj.吃力的,努力的,不流畅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

53

epoch

|

|

| n.(新)时代;历元 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

54

celebrity

|

|

| n.名人,名流;著名,名声,名望 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

55

distinguished

|

|

| adj.卓越的,杰出的,著名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

56

wren

|

|

| n.鹪鹩;英国皇家海军女子服务队成员 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

57

annexed

|

|

| [法] 附加的,附属的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

58

metallic

|

|

| adj.金属的;金属制的;含金属的;产金属的;像金属的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

59

wrought

|

|

| v.引起;以…原料制作;运转;adj.制造的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

60

consummate

|

|

| adj.完美的;v.成婚;使完美 [反]baffle | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

61

veins

|

|

| n.纹理;矿脉( vein的名词复数 );静脉;叶脉;纹理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

62

remarkably

|

|

| ad.不同寻常地,相当地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

63

devoted

|

|

| adj.忠诚的,忠实的,热心的,献身于...的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

64

solely

|

|

| adv.仅仅,唯一地 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

65

aberration

|

|

| n.离开正路,脱离常规,色差 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

66

attained

|

|

| (通常经过努力)实现( attain的过去式和过去分词 ); 达到; 获得; 达到(某年龄、水平、状况) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

67

discoursing

|

|

| 演说(discourse的现在分词形式) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

68

dexterity

|

|

| n.(手的)灵巧,灵活 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

69

celestial

|

|

| adj.天体的;天上的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

70

honourable

|

|

| adj.可敬的;荣誉的,光荣的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

71

majesty

|

|

| n.雄伟,壮丽,庄严,威严;最高权威,王权 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

72

astronomers

|

|

| n.天文学者,天文学家( astronomer的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

73

scarlet

|

|

| n.深红色,绯红色,红衣;adj.绯红色的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

74

astronomical

|

|

| adj.天文学的,(数字)极大的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

75

penetrating

|

|

| adj.(声音)响亮的,尖锐的adj.(气味)刺激的adj.(思想)敏锐的,有洞察力的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

76

stationary

|

|

| adj.固定的,静止不动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

77

elevation

|

|

| n.高度;海拔;高地;上升;提高 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

78

philosophical

|

|

| adj.哲学家的,哲学上的,达观的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

79

metropolis

|

|

| n.首府;大城市 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

80

observatory

|

|

| n.天文台,气象台,瞭望台,观测台 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

81

skilful

|

|

| (=skillful)adj.灵巧的,熟练的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

82

munificent

|

|

| adj.慷慨的,大方的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

83

patronage

|

|

| n.赞助,支援,援助;光顾,捧场 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

84

perseverance

|

|

| n.坚持不懈,不屈不挠 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

85

starry

|

|

| adj.星光照耀的, 闪亮的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

86

exalted

|

|

| adj.(地位等)高的,崇高的;尊贵的,高尚的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

87

enjoyment

|

|

| n.乐趣;享有;享用 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

88

sages

|

|

| n.圣人( sage的名词复数 );智者;哲人;鼠尾草(可用作调料) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

89

warriors

|

|

| 武士,勇士,战士( warrior的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

90

immortal

|

|

| adj.不朽的;永生的,不死的;神的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

91

trophy

|

|

| n.优胜旗,奖品,奖杯,战胜品,纪念品 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

92

ebb

|

|

| vi.衰退,减退;n.处于低潮,处于衰退状态 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

93

strand

|

|

| vt.使(船)搁浅,使(某人)困于(某地) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

94

reign

|

|

| n.统治时期,统治,支配,盛行;v.占优势 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

95

dominions

|

|

| 统治权( dominion的名词复数 ); 领土; 疆土; 版图 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

96

rivalry

|

|

| n.竞争,竞赛,对抗 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

97

blighted

|

|

| adj.枯萎的,摧毁的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

98

chivalry

|

|

| n.骑士气概,侠义;(男人)对女人彬彬有礼,献殷勤 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

| 欢迎访问英文小说网 |